FRESHWATER AQUARIUMS & TROPICAL DISCOVERY

HALFBEAKS ❙ Planted Tanks:

Secrets of Success ❙ “Cichlasoma” Cichlids ❙ Breeding Tiger Stingrays

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2014

$0/5&/54 r 70-6.& /6.#&3 EDITOR & PUBLISHER |

James M. Lawrence

INTERNATIONAL PUBLISHER |

Matthias Schmidt

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF |

Hans-Georg Evers

CHIEF DESIGNER |

Nick Nadolny

4

EDITORIAL

6

AQUATIC NOTEBOOK

by Hans-Georg Evers

SENIOR ADVISORY BOARD |

Dr. Gerald Allen, Christopher Brightwell, Svein A. Fosså, Raymond Lucas, Dr. Paul Loiselle, Dr. John E. Randall, Julian Sprung, Jeffrey A. Turner SENIOR EDITORS |

Matthew Pedersen, Stephan M. Tanner, Ph.D.

FEATURE ARTICLES 20

CONTRIBUTORS |

Juan Miguel Artigas Azas, Dick Au, Devin Biggs, Heiko Bleher, Eric Bodrock, Jeffrey Christian, Morrell Devlin, Ian Fuller, Adeljean L.F.C. Ho, Jay Hemdal, Neil Hepworth, Ted Judy, Ad Konings, Marco Tulio C. Lacerda, Neale Monks, Rachel O’Leary, Mark Sabaj Perez, Ph.D., Christian & Marie-Paulette Piednoir, Karen Randall, Mary E. Sweeney, Ben Tan, Ret Talbot TRANSLATOR |

Stephan M. Tanner, Ph.D.

ART DIRECTOR | DESIGNER |

30

Louise Watson

Reef to Rainforest Media, LLC 140 Webster Road | PO Box 490 Shelburne, VT 05482 Tel: 802.985.9977 | Fax: 802.497.0768 BUSINESS MANAGER |

48

54

by Sumer Tiwari

62

PRINTING |

Howard White & Associates

POTAMOTRYGON TIGRINA

by Jennifer O. Reynolds

72

Dartmouth Printing | Hanover, NH

service@amazonascustomerservice.com 570.567.0424 WEB CONTENT |

www.amazonasmagazine.com

www.reef2rainforest.com

by Thomas Weidner

78

DEPARTMENTS 88

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to: AMAZONAS,

PO Box 361, Williamsport, PA 17703-0361

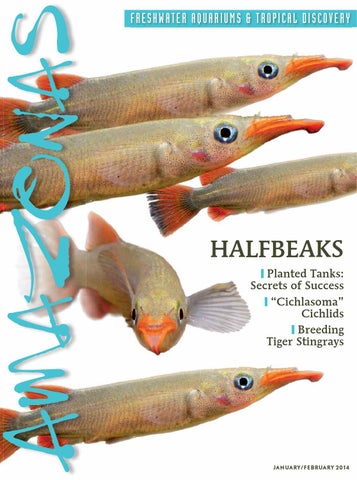

All rights reserved. Reproduction of any material from this issue in whole or in part is strictly prohibited. COVER:

Orange-Finned Halfbeaks, Nomorhamphus ebrardtii Image by Hans-Georg Evers

AQUARIUM CALENDAR

Upcoming events by Matt Pedersen and Ray Lucas

ISSN 2166-3106 (Print) | ISSN 2166-3122 (Digital)

AMAZONAS™ is a licensed edition of AMAZONAS Germany, Natur und Tier Verlag GmbH, Muenster, Germany.

AQUATIC TRAVEL: A TRIP ON THE RIO NEGRO

by Juan Miguel Artigas Azas

AMAZONAS™, Freshwater Aquariums & Tropical

Discovery, is published bimonthly in February, April, June, August, October and December by Reef to Rainforest Media, LLC, 140 Webster Road, PO Box 490, Shelburne, VT 05482. Periodicals postage paid at Shelburne, VT, and at additional entry offices. Subscription rates: U.S., $29 for one year. Canada, $41 for one year. Outside U.S. and Canada, $49 for one year.

HUSBANDRY & BREEDING: “CICHLASOMA” ORNATUM OR “CICHLASOMA” GEPHYRUM?

CUSTOMER SERVICE |

SUBSCRIPTIONS |

HUSBANDRY & BREEDING: BREEDING THE TIGER RAY,

James Lawrence | 802.985.9977 Ext. 7 james.lawrence@reef2rainforest.com Linda Bursell

AQUATIC PLANTS: A PLANTED PARADISE IN 18 GALLONS

Judy Billard | 802.985.9977 Ext. 3

NEWSSTAND |

HEMIRHAMPHODON KUEKENTHALI, THE MAGNIFICENT SARAWAK HALFBEAK

by Ronny Kubenz and Rainer Hoyer

ADVERTISING SALES |

ACCOUNTS |

THE HALFBEAKS OF SULAWESI

by Hans-Georg Evers

Linda Provost

EDITORIAL & BUSINESS OFFICES |

ZENARCHOPTERIDAE

by Jan Huylebrouck

Anne Linton Elston

ASSOCIATE EDITOR |

VIVIPAROUS HALFBEAKS OF THE FAMILY

90

RETAIL SOURCES

92

SPECIES SNAPSHOTS

97

ADVERTISER INDEX

98

UNDERWATER EYE

by Morrell Devlin

AMAZONAS 3

EDITORIAL AMAZONAS 4

Dear Reader, “When someone returns from a journey, he has stories to tell. That’s why I choose to take my hat and walking stick and go traveling.” So said Matthias Claudius (1740–1815). We aquarists are a traveling crowd, whether we’re visiting a jungle or a destination tropical fish shop, and we like to talk and write about our experiences. A report on a trip in search of fishes can be simple, or it can be structured almost like a scientific article. In this issue, we have put together a few reports that will bring you closer to the habitats of our aquarium inhabitants. We try to omit predictable travelog descriptions (I was cured of this early on, when I had to endure my uncle’s long-winded slide show narrations) and boring pseudoscientific discussion. The focus is on the details—for example, this issue includes a story on Brazil’s Rio Negro that is accompanied by magnificent images of blackwater fishes. We also like to present an overview of a particular species or group and its distribution. For years now—actually, since the birth of AMAZONAS—I have wanted to do a story about the quirky halfbeaks. My interest was piqued when I first visited my dream island, Sulawesi, in 2007. Since then I have returned several times, and have put together an overview of the halfbeaks of that island, something which has not been done before. It was difficult not to drift off into daydreaming during this self-assigned work. My heart and soul has gone into this article, and I confess that it might have become a bit too long! However, not every story in this issue is about halfbeaks. There is also a great article on the hard work of professional aquarists in Canada who are breeding stunningly beautiful Tiger Rays. Readers of the English-language edition will meet two nextgeneration planted-aquarium fanatics, Kris Weinhold and Sumer Tuwari. We believe that each issue of AMAZONAS should be just as diverse and vivid as the fishes we keep. I hope we have succeeded once again in putting together a tempting and colorful smorgasbord for you. Bon appétit!

5

AQUATIC

NOTEBOOK

Unexplained color changes in Loricariidae

Pseudacanthicus sp. L273 after the color change.

AMAZONAS Staff Reportt Aquarists are often treated to the sight of an armored catfish un-

6

The color change is developmentally regulated at the species level. For example, all Hypostomus luteus specimens recolor with advancing age, but each individual does so at a different pace; in Parancistrus aurantiacus, single specimens recolor bright yellow in nature, but not in the aquarium. In other species, the color change seems to be an individual phenomenon. Hormones might be crucial for the

initiation of this transition, and a hormonal malfunction in the individual animal would not affect the other animals in a group. One of our readers, Daniel Konn-Vetterlein, observed a complete color change in a Parancistrus nudiventris within three weeks (pers. comm.). However, we have never seen a yellow specimen of this species in nature. Konn-Vetterlein noted that his fish had been

M. KALUZA

AMAZONAS

dergoing a dramatic color change. This usually affects a single individual at a time and seems unconnected to anything its keeper has done. The body lightens up and eventually turns an orange or lemony color; sometimes the fish reverts to its original colors at the end of the process, which can take from several weeks to a year. The Panaqolus sp. LDA1/L169 specimen pictured on page 8 changed its color to orange and then back within a year. A few years later, it happened again.

Adult Cactus Pleco, Pseudacanthicus spinosus, undergoing color change. The original color pattern is still recognizable.

The transformation is almost complete.

AMAZONAS

H. TROST

Lemon-yellow Pseudacanthicus spinosus in the aquarium of Heinz Trost.

7

Manage Your Own Subscription It’s quick and user friendly

Normally colored specimen of Panaqolus sp. LDA1/L169.

Panaqolus sp. LDA1/L169, mid-change.

Go to www.AmazonasMagazine.com Click on the SUBSCRIBE tab Here you can: ● Change your address ● Renew your subscription ● Subscribe ● Buy a back issue ● Report a damaged or missing issue ●

Give a Gift! Other options: EMAIL us at:

AMAZONAS

service@amazonascustomerservice.com CALL: 570-567-0424 or WRITE:

AMAZONAS Magazine 1000 Commerce Park Drive, Suite 300 Williamsport, PA 17701 8

At several months of age, the fish is yellow with orange stripes.

This otherwise black Parancistrus nudiventris is slightly blurred.

made this color change several times before; the other individuals in his group remained unchanged. The color change in an adolescent Pseudacanthicus sp. L273 is quite spectacular, as you can see in the photos sent in by reader Markus Kaluza. If you want to see more examples, go to the highly recommended website www.l-welse.com/reviewpost/showproduct.php/product/1832/cat/15, where you can see photos of various species that undergo this yellow color change. (Use Google to translate.)

AMAZONAS

THIS PAGE: D. KONN-VETTERLEIN; OPPOSITE PAGE: H.-G. EVERS

given a particularly protein-rich diet prior to the process. Other catfish keepers have noticed similar color changes after changing to a high-protein diet, which is unnatural for these fish. Could this be the trigger in individual animals to switch the color via the metabolism? AMAZONAS reader Heinz Trost sent us pictures of an adult Pseudacanthicus spinosus that changed from its normal gray-brown to a bright lemon yellow and then back again within a few weeks. The fish had already

9

AQUATIC

NOTEBOOK

Plant enthusiast Kris Weinhold, 33, in his fishroom, with “farm tank” for plant propagation, back left.

TRAVELING THE FISH SCENE:

Kris Weinhold, Iron Aquascaping, and planted tank open secrets by Rachel O’Leary t I was sitting in an audience raptly watching an Iron Aquascaper Challenge between two aquarists, Jen Williams and Cavan Allen, and thoroughly enjoying the play-by-play commentary by Kris Weinhold. I had traveled to Herndon, Virginia, to speak at Aquafest, a convention hosted by three local aquatic clubs: the Capital Cichlid Association, the Greater Washington Aquatic Plant Association (GWAPA), and the Potomac Valley Aquarium Society.

10

TOP: RACHEL O’LEARY. LEFT: KRIS WEINHOLD

AMAZONAS

Kris Weinhold’s entry in the Aquatic Gardeners’ Association annual competition, a 33-gallon (125-L) aquascape.

Advanced aquarists choose from a proven leader in product innovation, performance and satisfaction.

MODULAR FILTRATION SYSTEMS Add Mechanical, Chemical, Heater Module and UV Sterilizer as your needs dictate.

BULKHEAD FITTINGS Slip or Threaded in all sizes.

FLUIDIZED BED FILTER

Completes the ultimate biological filtration system.

AQUASTEP PRO® UV

INTELLI-FEED™ Aquarium Fish Feeder

Can digitally feed up to 12 times daily if needed and keeps fish food dry.

BIO-MATE® FILTRATION MEDIA AIRLINE BULKHEAD KIT

Step up to new Lifegard technology to kill disease causing micro-organisims.

Available in Solid, or refillable with Carbon, Ceramic or Foam.

Hides tubing for any Airstone or toy.

LED DIGITAL THERMOMETER Submerge to display water temp. Use dry for air temp.

A size and style for every need... quiet... reliable and energy efficient. 53 gph up to 4000 gph.

Email: info@lifegardaquatics.com 562-404-4129 Fax: 562-404-4159 Lifegard® is a registered trademark of Lifegard Aquatics, Inc.

AMAZONAS

QUIET ONE® PUMPS

Visit our web site at www.lifegardaquatics.com for those hard to find items... ADAPTERS, BUSHINGS, CLAMPS, ELBOWS, NIPPLES, SILICONE, TUBING and VALVES.

11

12

Kris was a familiar face, as we are members of some of the same Nimphaea micrantha, a West African native plant new to the aquarium world, is sometimes clubs and have bumped into each known as Blue Egyptian Lotus or Blue Lily. other many times over the years. The aquascaping contest was great fun, and Kris did a terrific job narrating and educating the attendees on choices of substrates, hardscapes, and plants, layout, and lighting design. Somehow he easily held the crowd’s interest while the dueling teams of aquascapers frantically worked to complete their 20-gallon high tanks within an hour. This trip also gave me the opportunity to talk with Kris in his home fishroom and hear about his evolution as an aquarist 33-gallon “Bermuda Tank” features Ludwigia sphaeroand emerging player in the planted-tank world. He lives carpa, which he collected from the Eastern Shore of in Columbia, Maryland, with his wife, Lauren, and their Maryland, across the Chesapeake Bay from Washington. furry friends, two dogs and two cats. By day, he uses his While many aquarists focused on planted tanks consider degree in computer science to manage a team of web fishes secondary to their plants, Kris is also interested in developers for a medical non-profit organization. His the behaviors and breeding of his fishes. Obviously, he fishroom is a bright, welcoming haven that showcases prefers species that won’t damage his plants, and many the breadth of his aquascaping talents. He has several of his tanks feature interesting cichlids (Apistogramma, planted display tanks as well as a “farm tank” for growPelvicachromis, and Pterophyllum), barbs, Corydoras, and ing out new plants. loaches (Micronemacheilus cruciatus, the Dwarf Zebra “I pretty much maxed out at five or six tanks, totaling Hovering Loach, is his favorite). He also has an interest about 250 gallons. Since all of my tanks are high-light in shrimps and nano fishes for his smaller tanks, and with pressurized CO2 and fully planted, it becomes both says that the activity and color provided by the fishes and invertebrates are integral to his overall tank designs. expensive and time-intensive to keep and maintain too A life-long aquarist, Kris first became interested in many more than this. This number allows me to mainplanted tanks about 10 years ago when a co-worker intain several different aquascapes at one time, an emersed troduced him to Takashi Amano’s book Nature Aquarium setup, and a farm tank.” World. Kris was captivated and joined several online Kris collects wild plants during his travels as a speakplanted forums, as well as GWAPA, his local aquatic plant er, and he often incorporates them into his designs. The

BOTH: RACHEL O’LEARY.

AMAZONAS

A Blackbanded Sunfish, an East Coast native growing to just 4 inches (10 cm), with Black Neons in a tank with basalt rock hardscape and a profusion of plants.

AMAZONAS

49 13

Planted Ripariums

Ludwigia sphaerocarpa, a native plant Kris collected from the Eastern Shore of Maryland. He says it is just starting to gain attention in the aquatic plant world, and is not yet commercially propagated.

Grow easy-care riparium plants with your aquarium fish. t 3PCVTU QMBOU CBTFE ĂśMUSBUJPO t /P FYUSB $0 SFRVJSFE t *EFBM GPS DJDIMJET BOE PUIFS CPJTUFSPVT ĂśTI t #FBVUJGVM CMPPNT BOE GPMJBHF

www.RipariumSupply.com

BACK ISSUES

How deep is your collection? Enrich your aquatic library with back issues of AMAZONAS. All back issues are like new, in pristine condition in their original poly wrapping.

SPECIAL OFFER: Buy 3 issues or more AMAZONAS

at $8 each, 6 or more at $7each.

14

(plus shipping)

Go to www.reef2rainforest.com and click on the SHOP tab

club. His ďŹ rst planted tank was a reincarnation of the aquarium he had had through childhood—a 20-gallon (76-L) high. Through trial and error, and by reďŹ ning his equipment and techniques, Kris evolved into an expert in high-tech tanks. He notes that he â€œďŹ rst upgraded to power compact strip lights, starting with one and then adding a second. I tried do-it-yourself CO2 yeast reactors ďŹ rst to ensure that carbon dioxide really helped the plants. Then, I bought a simple Dupla CO2 regulator. Both of these things pushed me into regular CO2 fertilization. “The biggest challenge in a planted aquarium is establishing equilibrium in the tank and maintaining it,â€? Kris says. “For example, you set up an aquarium with new plant-speciďŹ c substrate and throw in a bunch of plants. There are nutrients in the substrate, so you don’t have to dose many fertilizers. The plants start growing, and all of a sudden the substrate nutrients aren’t enough. So you start dosing fertilizers, and the plants go crazy. Then you do a huge trimming, and it takes a little while for the plants to recover and take off again. You likely want to reduce your dosing slightly. If you do regular water changes you don’t have to worry about these things as much, but learning proper dosing takes time and trial and error. Likewise, if you add a new light to your aquarium, it changes how fast or slowly your plants grow.â€? Kris shares his experiences at www.guitarďŹ sh.org, a blog he started in 2006. He spends a lot of time describing his setups, explaining the trials and tribulations of the hobby, and reviewing new products. Recently he has been focusing on LED lighting, and is in the process of converting all of his older ďŹ xtures to LEDs. As more and more companies begin manufacturing and marketing products designed for planted aquaria, Kris says we can expect this area of the market to continue to expand, making it easier for those interested in planted tanks to ďŹ nd success. He started his blog as a journal, and recommends that every hobbyist “keep a photographic journal, especially aquascapers. It’s fantastic to be able to

AMAZONAS

go back and see how your tank has progressed from week to week and month to month. You learn how fast certain plants grow, when to trim them, and so on.” I asked about his “secret formula” for success with aquatic plants. Kris says it is not much of a secret, as it can all be found on his blog, but the following are his preferred choices for planted aquaria and his opinions on options currently available in the North American market: Substrate: “Mostly ADA (Aqua Design Amano) Aqua Soil, although I have tanks with other substrates, including a DIY of worm castings capped with old Aqua Soil. I’m constantly trying new things when they come out. By and large, I think that after six months, the substrate you use is less important, as it’s likely not providing much nutrition by that point. If you’re only keeping root-feeding plants, mineralized soil substrate may be an exception, but even that will benefit from extra fertilization at some point. For me, it’s worth the price for the aquarium substrate that holds plants down better, initially kick-starts the tank with nutrients, and looks a little bit more natural. There’s a large price range in aquarium substrates, and much of the choice comes down to aesthetics, which may or may not be worth the cost.” Lighting: “All LED. You need to ensure that the intensity of your light meets the light requirements of the plants you’re trying to grow. I would love to see all the manufacturers print PAR readings at standard depths on their boxes, so it would be easier to compare fixtures.” CO2: “Pressurized CO2, and turn it up! I crank it as high as I can without causing the fishes stress.” Fertilizers: “I dose dry fertilizers daily during the week. Monday, Wednesday, and Friday I dose macronutrients (NPK or Nitrate-Phosphate-Potassium), KNO3 (potassium nitrate for nitrate), and KH2PO4 (potassium phosphate for phosphate). Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday I dose micronutrients (trace elements plus iron). Sunday I do water changes.” Hardscape: “I’ve seen a ton of fantastic aquascapes done with hardscape materials that were free, collected nearby. Most of my hardscaping material falls in this category. I have also bought expensive hardscaping material that has a specific look or character that I couldn’t find nearby. It’s not necessary to spend a lot to be successful, but designer stones and wood can be the missing piece in your dream aquascape.” Other: “Do regular and consistent water changes and keep up on your filter maintenance and mulm/detritus removal to prevent too many algae-causing organics from building up in the tank.” As featured on the Reef2Rainforest/AMAZONAS blog, Kris was one of a panel of judges selected for the 13th Aquatic Gardeners Association (AGA) Aquascaping Com-

15

AMAZONAS

petition. Kris points out that the AGA’s website contains a full collection of photographic entries all the way back to 2000 (http://showcase.aquatic-gardeners.org). He says that everyone should look through them to gain inspira-

16

tion for his or her next tank. He reveals that every judge comments on every tank, and encourages anyone who wants to get better at aquascaping to submit a tank to the AGA. Even if you don’t win, you get valuable feedback on how to improve your skills. All entrants are automatically entered into Amano’s ADA competition. As a member of GWAPA and an ofďŹ cer of the board, which is hosting the next AGA Convention in the DC area, Kris offers the following advice to those entering an aquascaping competition: t 5BLF QJDUVSFT PG UIF QSPDFTT QBSticularly when designing your hardscape, to show how the aquascape will look in the ďŹ nal entry you submit. Better to catch problems early on. t 5BLF UIF FRVJQNFOU PVU PG ZPVS UBOL and put more light on top of the aquarium before you photograph it. t .BLF TVSF ZPVS TVCTUSBUF JT TNPPUI and level in front. t $MFBO ZPVS HMBTT t %PO U DSBN JO QMBOU TQFDJFT Choose 5 to 10 and repeat them throughout. Intersperse the species; wild plants don’t usually grow in monocultures. t .BLF TVSF ZPVS TVCTUSBUF BOE IBSEscape work well together. Don’t use white rocks and black substrate, or pea gravel with volcanic rock. t 'JTI TJ[F BOE UBOL TJ[F TIPVME NBUDI Don’t put a full-sized discus in a 20-gallon tank. In fact, smaller ďŹ shes are better— they won’t dominate the aquascape. t /P HJNNJDLT 8BUFSGBMMT BOE gnomes are fun, but the judges prefer to see natural scenes. Federal bans on importing or selling certain species can be a major problem. I asked Kris about the federal noxious weed list and recent attempts to pass legislation imposing blanket bans on speciďŹ c plants. “Some people are in favor of limiting the types of plants and ďŹ shes that we are allowed to keep to a small, approved list.

TOP LEFT AND RIGHT: KRIS WEINHOLD

Near right: A hardscape emerges as Kris creates a 12-gallon (45-liter) scene. Far right: The same Mr. Aqua Bookshelf Tank after several weeks of growth with bright LED light and carbon dioxide fertilization. He advises aquascapers to document their work with photographs.

Obviously this would destroy the hobby. That being said, noxious weeds and invasive species can severely damage our native environments, and it costs real money to control them in the wild. All aquarists must ensure that the flora and fauna they keep remain in their own aquaria. Never dump a plant or fish out in the wild, even if you originally collected it there. (It can acquire diseases or parasites while in captivity.) “It only takes one instance of an aquarist being linked to destroying a native ecosystem to have the legislative tide turn against us and limit our rights to keep what we take for granted now.” Kris offered these final words of wisdom: “Try every plant you can. I am often asked, ‘Is this an easy plant?’ The honest truth is that it depends. Different plants like different conditions, and tank conditions vary. Besides, if you kill a plant, you don’t feel nearly as bad as you do

if you kill a fish. So there’s really no excuse not to try a plant you’ve never heard of.” Rachel O’Leary breeds and sells nano livestock through her

company, Invertebrates by Msjinkzd, in Mount Wolf, Pennsylvania, http://msjinkzd.com/. REFERENCES

Amano, Takashi. 1994. Nature Aquarium World. TFH Publications, Neptune City, NJ. ON THE INTERNET

AMAZONAS Magazine Blog (AGA Winners): http://www.reef2rainforest. com/2013/02/15/aga-aquascape-winners-2012/ Aquatic Gardeners Association (AGA): http://showcase.aquatic-gardeners. org/ Kris Weinhold’s Blog: www.guitarfish.org

AMAZONAS 17

AQUATIC

NOTEBOOK

Betta hendra:

18

by Stefan van der Voort t In 2009, a new Betta species was imported from Kalimantan Tengah, the Indonesian province on the island of Borneo, for the first time. It later found its way into the hobby under various trade names, including “Palangkaraya,” “Sabangau,” “Sengalang,” and “Palangka.” Now the species has been named Betta hendra (Schindler & Linke, 2013) in honor of its discoverer and first exporter, Tommy Hendra of Kurnia Aquarium in Kalimantan Tengah, Borneo. The new species lives in the marshes of the Sungai Sebangau drainage south and west of the city of Palangkaraya. In May 2011, the water there had the following values (quoted from Schindler & Linke, 2013): pH ~4, electrical conductivity 6 μS/cm, temperature 83.3°F (28.5°C). The slow-moving water flowed among trees and bushes that offered a lot of shade. The water depth was only 2–20 inches (5–50 cm). B. hendra belongs to the Betta coccina group. The species differs from the other species of the group in color—its body and unpaired fins are bright green, and the other members of the group are darker in color—and, except for a large lateral spot in some species, it lacks the

iridescent scales. B. hendra differs from B. uberis by the smaller number of dorsal fin rays. Hendra’s fighting fish is a foam nest–builder that grows to a length of about 4.5 cm (1.75 inches). It is available from specialized aquarists. Because it is so attractive, it is likely to become well established among labyrinth fish friends. REFERENCES

Schindler, I. and H. Linke. 2013. Betta hendra—a new species of fighting fish (Teleostei: Osphronemidae) from Kalimantan Tengah (Borneo, Indonesia). Vert Zool 63 (1): 35–40. Van der Voort, S. and T. Christoffersen. 2011. Betta sp. “Palangkaraya”—ein neuer Kampffisch von Borneo. AMAZONAS 36, 7 (4): 40–43.

S. V. D. VOORT

AMAZONAS

a new fighting fish from Kalimantan Tengah

24/7 VISIT OFTEN: • Web-Special Articles • Aquatic News of the World • Aquarium Events Calendar • Links to Subscribe, Manage Your Subscription, Give a Gift, Shop for Back Issues • Messages & Blogs from AMAZONAS Editors • Coming Issue Previews • New Product News • Links to Special Offers

www.Reef2Rainforest.com HOME of AMAZONAS, CORAL, & MICROCOSM BOOKS

AMAZONAS AMAZONAS

Our new website is always open, with the latest news and content from AMAZONAS and our partner publications.

19 19

C OV E R

STORY Portrait of Nomorhamphus ebrardtii, the OrangeFinned Halfbeak: hard to find but a great aquarium candidate with vivid colors and ease of keeping.

by Jan Huylebrouck t Halfbeaks have been known to science for almost 200 years. At least three of the five genera of the family Zenarchopteridae, which was only established in 2004, are characterized by giving birth to live young—vivipary or viviparity—that have developed as embryos in the body of the mother. Many of the Southeast Asian halfbeak species bear striking fin colors and show interesting behaviors. Still, viviparous freshwater halfbeaks have never achieved the popularity of other livebearers. Perhaps the time has come for that to change.

VIVIPAROUS AMAZONAS

HALFBEAKS

20

of the family Zenarchopteridae

Ambush predators The eponymous and most conspicuous feature of the halfbeaks is their extended mandible (lower jaw), although in some Nomorhamphus species it is barely longer than the upper jaw. In juvenile animals, the lower and upper jaws are initially about the same length. Among Nomorhamphus and Hemirhamphodon species, the extended mandible often has a downward-bent tip that is intensely colored in dominant males, suggesting a signaling function. However, the extended mandible has another important function: it aids in food intake. There is a thin cutaneous rim on both sides. The fish swims sideways toward its victim, the movable upper jaw breaks the water surface, and the prey is shoveled by the lower jaw and the rims into the mouth. Skin folds between the upper and lower jaws increase the mouth opening, which leads to additional suction. Stomach analyses have shown that many halfbeaks consume flying prey, mainly terrestrial insects that have fallen onto the surface of the water. Some scientists have posited that the long lower jaw is not really a jaw at all but a specialized chin. A 2009 online post from the Wainwright Lab at the University of California, Davis states, “One idea that has some support is that the long chin is part of a specialized sensory device. Montgomery & Saunders (1985) showed that there are a series of lateral line pores along the length of the lower jaw, with neuromasts in between these pores. They argued that this long structure, equipped with the lateral

line pits, may function in prey detection.” (See References, page 28.) Halfbeaks are surface-oriented, with the exception of members of the genus Nomorhamphus, which are also found in other water regions. The sensory cells of the eyes are optimized for seeing upward and to the side. On the top of the head are the nasal barbels that represent the olfactory organ, atypically external for a bony fish. With their help, the olfactory cells are constantly exposed to water, even when the fish is standing still and waiting for prey. The hydrodynamic pike shape betrays that halfbeaks are mainly ambush predators that gain speed with the help of their tails and anal and dorsal fins.

Posthumous description In 1823, Dermogenys pusilla was the first viviparous halfbeak species and genus described by the young researchers Heinrich Kuhl and Johan van Hasselt in a letter that was sent to C.J. Temminck, the director of the Dutch Natural History Museum in Leiden. In 1820, Kuhl and van Hasselt were commissioned by the Dutch government to explore the wildlife of

AMAZONAS

H.-G. EVERS

Habitat of Dermogenys sumatrana in the estuary of Sungai Sarin near Kualatungkal, Sumatra. The species lives here in brackish water but is also found many miles upriver in pure, fresh water.

21

Typical habitat of Dermogenys siamensis in Chanthaburi, Thailand. The species colonizes rivers, ponds, and swamps, where it waits under protective cover for food such as insects.

Java, then part of the former colony of the Dutch East Indies. They started their collection activities in Bogor, Java, where they found D. pusilla in the ponds of the local botanical garden. Even today, you can catch this species there. In September 1821, Kuhl died a few days before his 24th birthday as a result of liver inflammation. Van Hasselt continued the work but followed his friend to the grave only two years later. Nevertheless, these men are regarded as the first describers, as the species was discovered and described during their lifetime. Last year, as part of a project sponsored by the Society for Ichthyology, I had the opportunity to study the conserved specimens of the genus Nomorhamphus in the ichthyological collection of the Zoological Museum in Bogor. I also visited the Dutch cemetery

Left: Habitat of Hemirhamphodon phaiosoma near Putussibau in the upper Kapuas River on Kalimantan, Borneo. The black waters here are very soft and acidic with temperatures of 81–84°F (27–29°C). The closely related Hemirhamphodon kapuasensis should also occur in these habitats in the upper Kapuas. Further downstream, the common Hemirhamphodon pogonognathus, with an extraordinarily long beak, inhabits similar places.

AMAZONAS

Below: Holotype of Nomorhamphus towoetii in the Zoological Museum Hamburg.

22

MIDDLE: H.-G. EVERS; ALL OTHERS: J. HUYLEBROUCK

Right: Andropodium of Nomorhamphus rex. The tridens flexibilis consists of the spiculus (SP) and the spinae (SN), which are important for the taxonomy of Nomorhamphus and Dermogenys. Adapted from Huylebrouck et al., 2012.

where Kuhl and van Hasselt are buried, which is hidden in a bamboo grove in the botanical garden.

Males with a trident At least three genera, namely Hemirhamphodon, Dermogenys, and Nomorhamphus, are viviparous. However, it must be mentioned that Hemirhamphodon tengah is the only representative of its genus that deposits internally fertilized eggs. The reproductive biology of the genus Tondanichthys is completely unknown. Tondanichthys kottelati is known only from museum material consisting of young and probably immature animals used for the description in 1995. The reproductive biology of the genus Zenarchopterus is somewhat unclear, but we do know that the eggs are fertilized internally. The males of the Hemirhamphodon species are unique

The shared grave of Kuhl and van Hasselt in Bogor, Java.

Right: Type specimen collection in the Zoological Research Museum Alexander Koenig, Bonn, Germany.

AMAZONAS

in that they are larger than the females. They have the same modified anal fin found in males of the other two viviparous genera. In Nomorhamphus and Dermogenys, the andropodium is formed from the first five to seven rays of the anal fin. In Hemirhamphodon, the andropodium usually consists of rays five through eight; the fifth and seventh or eighth rays are usually thickened and extended. In Dermogenys and Nomorhamphus, the andropodium is modified further. The second ray is especially remarkable. At its end there is a structure called the tridens flexibilis (flexible trident), which is important for the taxonomy and species identification because it looks different in almost every species. Despite detailed knowledge of the morphology of the reproductive organs, we know next to nothing about their function. The mating of Nomorhamphus lasts only 1/25 of a second. It is assumed that the sperm packets are passed through a membranous groove between the second and fourth rays of the anal fin to the tridens flexibilis, and from there into the female genital opening.

23

Hemirhamphodon phaiosoma is a beautifully colored species. H. kapuasensis is very similar but so far, its import has only been rumored.

Female Dermogenys sumatrana are gray. They share this trait with almost all species in the genus.

AMAZONAS

It is not clear whether or not the andropodium is inserted into the female genital opening; it seems unlikely because an axial rotation of the andropodium would be necessary, and that has never been observed. However, it could be that lateral huddling of sexual partners that rotate around their own axis make this possible. Such observations have been made but poorly documented. It is speculated by some that the andropodium is actually used as a clasping organ during mating. The courtship of Dermogenys and Nomorhamphus is striking in that the males “nip” with their mouths near the female’s genital opening. Presumably, this is to sense female hormones and ascertain whether the female is ready to mate.

24

Male Dermogenys, for instance D. sumatrana, often show red in the dorsal fin.

The anal fins of the male Zenarchopterus are modified, but the modified rays vary from species to species. In at least some members of this genus, the extended dorsal fin in combination with the anal fin serves as a kind of clip during mating to immobilize the female laterally.

Types of vivipary The female reproductive biology of the sister genera Dermogenys and Nomorhamphus was studied in more detail by Meisner and Burns (1997). Five different types of vivipary were found. Types I and II are characterized by an intrafollicular gestation. The embryos thus develop mainly in the follicles and reside only a short time in the

The halfbeaks often have peculiarly shaped beaks, and sometimes the skittish animals damage them on the aquarium glass. Injuries like this one on Hemirhamphodon phaiosoma can result.

ovary, to be born with the next ovulation. Embryos of type I lose mass during their development, suggesting that they are lecithotrophic (feeding only on existing yolk). In contrast, embryos of type II gain mass during development, due to the provision of nutrients by the mother (matrotrophy). In addition, type II differs from type I by viviparous superfetation, in which several broods can be fertilized in succession because the female stores sperm. As a result, up to three broods can develop simultaneously in the ovary. The different stages of development can be easily recognized. It may not look right, but this is what the beak of this Nomorhamphus liemi Types I and II occur in Nomorhamphus vivipara, a species really looks like. endemic to the Philippines, and among Dermogenys. Types III to V are characterized by intraluminal gestation. In this form of viviparity the embryos stay for only a short time in the ovarian follicles before migrating to the ovarian lumen, where they Mating of Hemirhamphodon tengah. This species lays internally fertilized eggs instead of giving birth to live develop. Embryos of type III exhibit young, as other Hemirhamphodon species do. superfetation and matrotrophy and are typical for Nomorhamphus species endemic to the Philippines. Type IV, however, shows no superfetation. Here the embryo is supplied by the mother, but in a different way. While the embryos of type III are supplied with nutrients through highly modified structures in the ovary and embryo, these modifications are ab-

ALL: H.-G. EVERS

AMAZONAS

Two Nomorhamphus cf. towoetii males “nip” near the anal region of a female, perhaps to sense hormones.

25

Stillborn and dead eggs and embryos of Hemirhamphodon kuekenthali. The different stages of development of the embryos are clearly visible. The probable cause of death is the decomposed young ďŹ sh at the top.

26

TOP: R. KUBENZ; BOTTOM: H.-G. EVERS

AMAZONAS

Members of the genus Zenarchopterus, such as Zenarchopterus dispar, are rarely imported. We know little about their reproductive strategies.

sent in type IV. Perhaps they absorb the nutrients from ovarian fluids. It gets really exciting with the gestation of type V, demonstrated by Nomorhamphus ebrardtii. This halfbeak is quite widespread in the mountain streams of Sulawesi and is often the only species of this genus encountered in the German aquarium trade. In this species the embryos are also supplied with essential nutrients, but this happens in a more spectacular fashion. The embryos feed on eggs (oophagy) and smaller siblings (adelphophagy). Adelphophagy is not unique among halfbeaks; it is well documented in some species of sharks.

Few aquarium observations It appears that superfetation in Dermogenys and Nomorhamphus occurs only in species in which the embryos are supplied with nutrients and gain weight. In addition, matrotrophic species produce more numerous but smaller offspring than lecithotrophic species. Unfortunately, it is currently not known exactly how long the females are pregnant, how many pups they carry, or how big the animals are at birth, because long-term observations are scarce at the moment. The few observations on this subject mentioned in the aquarium literature were collected by Greven (2006). According to him, the number of fry produced by Dermogenys pusilla varies from 9 to 165, but numbers of over 100 are exceptional; most females drop a maximum of 40 babies at once. Nomorhamphus females bear far fewer; usually there are no more than 12 to 16. Meisner and Burns (1997) have counted pups during their study on viviparity. They counted up to 20 embryos in females with type I vivipary, up to 36 in type II, and up to 10 animals in types III and IV (there was no data for type V). In Hemirhamphodon, the numbers are still largely unknown. Generally, a swollen female genital region is a sign of impending birth in viviparous halfbeaks. The babies are born head or tail first, usually in the protection of aquatic plants or other cover. Viviparous halfbeaks are very interesting and attractive aquarium inhabitants. As mentioned earlier, we are still in the dark about some reproductive details, which is why I would like to appeal to all aquarists and ask them to accurately observe their halfbeaks and publish their results for the benefit of all.

The family Zenarchopteridae currently includes about 55 species from five genera: Dermogenys, Hemirhamphodon,

Most species of the genera Dermogenys, Nomorhamphus, and Hemirhamphodon are easily maintained the aquarium. Because they prefer to swim near the surface, they mix well with other peaceful fishes that have approximately the same demands in terms of water quality but populate other levels of the aquarium. A few floating plants, a good filtration system with current, and regular water changes are basic requirements to maintain these fishes under appropriate conditions. The recommended water temperature depends on the particular area of origin. Tank size: The size of the aquarium depends on the adult size of the species. The larger Nomorhamphus need a 36-48-inch (90-120 cm) tank, larger if it is a territorial species. The smaller Dermogenys and Hemirhamphodon can be kept in 24-inch (60-cm) aquariums. Some species, especially if wild-caught, are initially quite shy and bolt immediately. Floating plants provide them with the appropriate cover. Without it, the animals can injure their sensitive beaks on the glass walls. Feeding: Halfbeaks are ambush predators that swim all day just under the surface and try to swallow everything that falls on it. Flake food and small granules are readily accepted. If you want to feed your animals really well, offer them cultured fruit flies (Drosophila) or collect meadow insects in the summer. Halfbeaks that have been fed with insects have larger broods and look healthier. The size and texture of foods can be important: Nomorhamphus tends to grab large pieces of food, such as hard food tablets, and this often causes the upper jaw to break. It then stands straight up and stays that way. If feeding dry pellets, be sure they are small in size or pre-soaked to soften them. Breeding: If you want to raise numerous juveniles, capture the pregnant females with a large net coming from below and place them into a small aquarium prepared with dense floating vegetation. There the females can carry the fry and drop the young fish in peace. The mothers have an inhibition threshold and do not initially harm the fry. These inhibitions soon disappear, so the females should be returned to the parental tank. If it is an aggressive species, they should be placed in another aquarium for recovery. A later return to the group is not a problem. —Hans-Georg Evers

Nomorhamphus, Tondanichthys, and Zenarchopterus. In contrast to the other genera, the representatives of the genus Zenarchopterus occur not only in brackish and fresh water but also in marine habitats. Their range extends from East Africa to Southeast Asia and Samoa to southern Japan; hence, they have the widest distribution among the zenarchopterids. The little-known genus Tondanichthys, with a single species, is known only from Lake Tondano on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi. The

AMAZONAS

Taxonomy of the halfbeaks

Halfbeaks in the Aquarium

27

species of the genus Hemirhamphodon differ from the other species in that they also bear teeth on the extended part of the lower jaw. Hemirhamphodon colonize small and moderately fast-flowing, soft and humic freshwater streams and rivers in the forested lowlands of southern Thailand, Malaysia, Sumatra, Borneo, and Java, which are rich in rainfall. Dermogenys is common in fresh and brackish waters throughout Southeast Asia. The species of this genus occur in Myanmar, Bangladesh, Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, India, Malaysia, Sumatra, Borneo, Java, Brunei, the Philippines, and Sulawesi. Dermogenys pusilla in particular seems to have become a synanthrope (a species that lives near and benefits from an association with humans) and is found in ponds and rice fields, but also occurs in mountain streams and coastal regions. Nomorhamphus is dependent on fresh water and occurs mainly in the mountain streams of Sulawesi and the Philippines. At least two species are also found in the great lakes of Sulawesi. The family Zenarchopteridae (viviparous halfbeaks) belongs to the order Beloniformes, which is a sister order of the viviparous livebearers (Cyprinodontiformes) in the superorder Atherinomorpha. Until 2004, Zenarchopteridae only had the status of a subfamily (Zenarchopterinae) of the family Hemiramphidae (halfbeaks). However, detailed morphological and genetic analyses by Lovejoy et al. (2004) showed that the viviparous halfbeaks are

more closely related to the sauries (Scomberesocidae) and needlefishes (Belonidae) than to the halfbeaks of the family Hemiramphidae. These, in turn, are closely related to the flying fishes (Exocoetidae). A very recent study of Southeast Asian Zenarchopterids (de Bruyn et al., 2013) suggests that the species of the genus Dermogenys endemic to Sulawesi are more closely related to Nomorhamphus than to the other Dermogenys species. This suggests that the genus Dermogenys constitutes an artificial group of fishes that is not monophyletic and requires a revision. However, further studies are needed to solve this problem permanently. Acknowledgments: I would like to thank Anna Schellenberg (SMNS, Stuttgart) and Fabian Herder (ZFMK, Bonn) for their help and inspiration in creating this article. I would also like to thank the ichthyology departments of MPE (Bogor, Java, Indonesia), ZMH (Hamburg, Germany), and the Society for Ichthyology for the opportunity to examine the viviparous halfbeaks in their collections. ON THE INTERNET

Complete online references for this article: http://www.reef2rainforest. com/references-viviparous-halfbeaks-of-the-family-zenarchopteridae/ Wainwright Lab, University of California, Davis blog post: “Mysteries in Fish Functional Morphology 2. Halfbeaks.” Online at http://fishlab.ucdavis. edu/?p=66.

Does size matter to you ?

AMAZONAS

We bet it does. Trying to clean algae off the glass in a planted aquarium with your typical algae magnet is like running a bull through a china shop. That’s why we make NanoMag® the patent-pending, unbelievably strong, thin, and flexible magnet for cleaning windows up to 1/2” thick. The NanoMag flexes on curved surfaces including corners, wiping off algal films with ease, and it’s so much fun to use you just might have to take turns. We didn’t stop there either- we thought, heck, why not try something smaller? So was born MagFox®, the ultra-tiny, flexible magnetically coupled scrubber for removing algae and biofilms from the inside of aquarium hoses. Have you got us in the palm of your hand yet?

28

www.twolittlefishies.com

The 26-Member Northeast Council of Aquarium Societies hosts their

39th Annual Convention March 28-30, 2014 CROWNE PLAZA HOTEL, CROMWELL, CT

www.northeastcouncil.org FEATURING THESE SPEAKERS! • Rick Borstein • Dr. Ted Coletti • Ken McKeighen • Matt Pedersen • Roxanne Smolowitz • Mark Soberman

Expert Speakers • Judged Fish Show • Giant Sunday Auction • Silent Auction Buffet Dinner • Hospitality Suite sponsored by AMAZONAS Magazine

AMAZONAS

Image: Matt Pedersen

• Kris Weinhold

29

C OV E R

STORY

by Hans-Georg Evers t In recent years, the big, sprawling Indonesian island of Sulawesi has received more and more attention from the aquarium world. Quite a few aquarists have been seduced by the unimaginably beautiful shrimps and snails that occur there. The island is also home to some almost unknown species of fascinating fishes.

Hungry Nomorhamphus megarrhamphus pounce on anything that falls on the surface of Lake Towuti.

THE HALFBEAKS

AMAZONAS

Overlooking Lake Towuti in the central highlands of Sulawesi.

30

THE FRESH WATERS OF SULAWESI are extremely species-poor. In the clear streams and rivers of the highlands and in the densely populated lakes, sometimes there are only one or two native species, competing against a broad range of invasive or introduced species. Both the ricefishes of the genus Oryzias (family Adrianichthyidae) and the viviparous halfbeaks in the family Zenarchopteridae have their centers of distribution on Sulawesi. The Adrianichthyidae are not killifishes but belong, with the Zenarchopteridae, to the order Beloniformes. Livebearing (viviparous) freshwater halfbeaks are a dominant fish group on the island. Many of them are endemic to Sulawesi. They share that distinction with another very interesting group of fishes: the sailfin silversides of the genus Telmatherina (family Telmatherinidae, order Atheriniformes). Each reasonably intact, pure freshwater habitat of the island is home to at least one member of the three

groups mentioned. Usually a halfbeak species occurs together with a Telmatherina or Oryzias species, and they are typically accompanied by one or two gobies. The closer you get to the coast, the scarcer the halfbeaks become. However, in the waters of the highlands they are ubiquitous. Nomorhamphus, in fact, are found only in the highlands; some Dermogenys species also occur in the lowlands, but far from the coast. Gobies dominate the fish fauna near the coast. The ancestors of all these fish species are marine in origin, so these are secondary freshwater fishes. We find a greater diversity of native fishes, mainly from the families Adrianichthyidae and Telmatherinidae, in the famous lakes in the highlands of Central Sulawesi: the Malili Lakes and those located north of Poso and Lindu. With a few exceptions, the halfbeaks live in cooler riverine habitats. This article focuses on the halfbeaks, but all the

OF SULAWESI Sulawesi Sea

NORTH SULAWESI

Gorontalo Molucca Sea

Gulf of Tomini Donggala

Luwuk

Palu Poso WEST SULAWESI

insula r Pen Timu

CENTRAL SULAWESI Kolonodale

Gulf of Tolo

Malili Mamuju

Palopo

ra

insula n Pen Selata

Kendari

SOUTHEAST SULAWESI

AMAZONAS

Flores Sea

la

Makassar

Gulf of Boni

North Banda Basin

su

SOUTH SULAWESI

nin Pe

other beautiful endemic species and their habitats certainly warrant more attention as well. Indeed, it is very likely that increasing human pressure (slash and burn land clearing, palm oil agriculture, mining, migration, and the invasion of foreign species) will impact most habitats. Sulawesi has no tigers or elephants, animals that often play a role in protection campaigns. Although most people are unaware of it, this unique island on the Wallace Line, with all its endemism and undiscovered beauty, is slowly but inexorably losing its biological riches. I have long pondered how I could write this article without having it degenerate into a simple list of species and their localities. I decided to structure the piece around the different habitats and their inhabitants, starting with the lacustrine or lake species.

GORONTALO

ar ng Te

TOP: C. C. REUSCH; BOTTOM: H.-G. EVERS

Makassar Strait

Manado

31

In the crystal clear water of Lake Matano, Nomorhamphus weberi prefers to live near the shore, in the shade of riparian vegetation.

Nomorhamphus weberi

Still waters In addition to the three species listed here, which are all found in large lakes, you could include the Dermogenys that inhabit the swampy regions and smaller ponds. However, since they occur in greater numbers in rivers, I would like to focus here on three species: Tondanichthys kottelati, Nomorhamphus weberi, and N. megarrhamphus. Tondanichthys kottelati

AMAZONAS

In the north of Sulawesi, near the tip of the Manado peninsula, lies Lake Tondano. From there Collette described, in 1995, the monotypic and almost unknown genus and species Tondanichthys kottelati. I have not yet visited this area, but I have asked several friends to look for the species. They reported that the lake has degenerated into an algae broth as a result of fish cages and severe pollution from the people settling there in recent decades (P. Debold, M. Kokoscha, pers. comm.). In Lake Tondano and in a smaller adjacent lake, there are no other fishes except Tilapia and Gambusia. Is Tondanichthys extinct?

32

Two species of lacustrine halfbeaks still live in Lake Matano, Lake Towuti, and Lake Mahalona in the central highlands. Once described as Dermogenys, they have since been transferred to the genus Nomorhamphus (Meisner, 2001). This shows how difficult the taxonomy of the fishes of the family Zenarchopteridae is (see also the contribution by Huylebrouck). In the warm waters of Lake Matano (84–88°F/29– 31°C at 13 feet/4 m), a very pretty halfbeak lives in large shoals just below the surface, mostly in the shelter of overhanging vegetation. In some areas, I could make out hundreds of these fish. With their steel-blue bodies and orange-yellow beaks, they are very attractive. Unfortunately, we never succeeded in bringing live animals home and breeding them in the aquarium. Like many other fishes in the lake, Nomorhamphus weberi is extremely sensitive. Nomorhamphus megarrhamphus

With its yellow and black finnage, Nomorhamphus megarrhamphus from Lake Towuti has a certain appeal. However, a successful import has yet to be carried out. This fish colonizes the shallow shore areas in large shoals, waiting just below the surface for dropping insects. They can swallow large prey, as Christian Reusch’s accompanying photo on page 31 impressively demonstrates. On my first trip to Lake Towuti in 2007, my friend

Nomorhamphus weberi is an attractive species but very sensitive to being transported.

Nomorhamphus megarrhamphus is skinny and has yellow fins.

Jeffrey Christian and I caught large quantities of these halfbeaks in one draw with a very long seine. It was remarkable how many heavily pregnant females there were in the net. Despite being moved carefully with a cup from the seine into waiting tubs, the animals died within a few minutes. I barely managed to take some adolescent fish to the hotel for the evening photo shoot. The stress of capture immediately did them in. Indeed, in his 1982 description, Brembach reported that they were very sensitive. On the night of our first day the moon was new, and the next day we made two very interesting observations. Early in the morning, the surface of the lake was dotted with thousands of white flowers. The water plants Ottelia mesenterium, which are abundant in the lake, had all opened their flowers at the same time during the pitch-dark night. And while snorkeling, I encountered thousands of newborn Nomorhamphus megarrhamphus moving in large swarms through the water. That was the only time during my three trips to the Malili Lakes that I found newborn fry, but it was also the only time I was there on a moonless night.

Dermogenys species One of the two originally described and still valid Dermogenys species from Sulawesi is Dermogenys orientalis. Max Weber described this species in 1894, based on material from the Maros and Palupa Rivers near the village of Tempe, South Sulawesi. The other valid Dermogenys species is Dermogenys vogti from the southwestern tip of Sulawesi Selatan, in the highlands of Topobulu. Unfortunately, I could not find this place during my trips, nor could any of the locals direct me to such a place. The first description is simply a descriptive text, without pictures or figures. The figure in Meisner (2001) shows a relatively deep-bodied species with a short beak, almost like Nomorhamphus. So far, I could not corroborate this species, but there are three other species whose determination is still pending. Dermogenys orientalis

The traveler who comes to Sulawesi usually lands at the airport of Makassar, the capital of the island, in the southwest of the province of South Sulawesi (Sulawesi

AMAZONAS

ALL: H.-G. EVERS

In the aquarium, male Dermogenys orientalis always swim close to cover and wait for a chance to mate with the females “standing” near the surface.

33

Dermogenys live in the shelter of overhanging vegetation in lowland rivers like this one near Lampuaua.

Selatan). It is worth taking the time to travel by car to the nearby highlands of Maros and admire the karst mountains and their unique flora and fauna. To foster tourism, the Bulusaraung National Park was established in 2004. The park is famous for its numerous butterflies and beautiful waterfall on the Bantimurung River. In addition to the Celebes Rainbowfish, Marosatherina ladigesi, we found two halfbeaks in the Bantimurung. This river above the waterfall is the type locality of Dermogenys montanus Brembach, now a synonym of Dermogenys orientalis. The water flows quickly over a

stony bed. The pH is quite high at 8.0 (conductivity 360 μS/cm), and the water temperature is moderate at 77°F (25°C). Outside the park boundaries, below the waterfall, we caught Dermogenys orientalis relatively easily with a net. In addition, we collected several large females of a Nomorhamphus species that proved to be relatively sensitive and were therefore released. If I had known that this would be my only opportunity to collect Nomorhamphus brembachi alive, I would have tried everything to catch more animals.

AMAZONAS

Female Dermogenys orientalis are quite aggressive; they are constant skirmishing and sparring with open beaks.

34

Female Dermogenys sp. “Sungai Lampuauá”

D. orientalis is a very pretty and robust species. It exhibits red fins and metallic-green flanks when it is content. A unique feature is the aggressiveness among the females, which is absent in any other species. If the aquarium is too small, the dominant female fights all rivals, attacking them with an open mouth. It is not unusual to observe mouth or “beak wrestling.” I have only witnessed this form of competition in males of two local variants of Nomorhamphus ebrardtii. A large aquarium with dense surface vegetation is required for this species, should you wish to keep and propagate them successfully. Large females (3 inches/8 cm) in my care dropped over 30 good-sized juveniles (0.4 inch/1 cm long) that ate Artemia nauplii immediately. It was striking that despite the best feeding and frequent water changes, the offspring reached less than two-thirds of the size of wild-caught animals and only a few juveniles reproduced later.

later, in the aquarium, they turned red. The species is not very aggressive and is easy to maintain, even in small aquariums (15 inches/60 cm long). As with other Dermogenys, breeding these imported wild-caught animals was easy, but the F1 females did not breed. Only once did my captive-bred animals produce offspring, so they soon died out. Other aquarists to whom I had passed on F1 juveniles were not successful either. Dermogenys sp. “Wailanti”

In 2008, I found the inconspicuous species Dermogenys sp. “Wailanti” in the province of Sulawesi Tengah, in the lowlands of Lake Poso in various clear-water rivers and in the swamps and ponds near Kolonodale on the east coast. In Sungai Wailanti, Dermogenys sp. “Wailanti” was numerous. Each cast of the frame net beneath the embankment produced several animals. This species lacks any kind of color, so it probably has limited interest for aquarists.

Jeffrey Christian, Peter Debold, and I caught this large species, which grows up to about 3 inches/8 cm (adult females), at the northern end of the province of South Sulawesi (Sulawesi Selatan), north of the village of Masamba in the coastal lowlands. Sungai Lampuauá (referred to on some maps as Sungai Lamogawa) is a shallow, clear-water stream with a high flow rate (pH 8.16, 134 μS/cm, 82.6°F/28.1°C). Under some bushes near the shore, Peter and I captured several dozen fish with the seine. After being caught, the fins were deep orange;

Dermogenys sp. “Malaulu”

The gray species Dermogenys sp. “Malaulu” is very similar to Dermogenys sp. “Wailanti,” but is more elongate and lives on the other side of the central highlands near the Malili Lakes in the lowlands of Bone Bay, in a clear, fastflowing river called Sungai Malaulu (pH 8.0, 252 μS/cm, 79.7°F/26.5°C). As we hunted for these small fish that no one bothers to eat, the Indonesians were washing their cars in the same place, commenting loudly about how colorless the

AMAZONAS

ALL: H.-G. EVERS

Dermogenys sp. “Sungai Lampuauá”

35

Dermogenys sp. “Wailanti” is plain gray.

fish were. My travel partner, Christian Reusch, and I did not get discouraged, and collected a number of animals. We are sure that Dermogenys sp. “Malaulu” is not easy to identify scientifically.

Nomorhamphus from riverine habitats

AMAZONAS

The quirky Nomorhamphus occur on the island of Sulawesi and in the Philippines, from which a total of seven species have been described. Ten species from Sulawesi are currently considered valid and others are likely to be added. I was able to confirm most described and some undescribed species in their natural habitats on Sulawesi. I report on them here by location, beginning in the highlands of Maros, the place from which the first Nomorhamphus arrived in the hobby.

36

Nomorhamphus liemi

In the mid-1970s Dieter Vogt, then editor of the German aquarium magazine DATZ, made a few trips to

Sulawesi with biologist Manfred Brembach. These trips, which were supported by the Indonesian export company Vivaria Indonesia, resulted in several descriptions of halfbeaks that might upset some people today because of their unorthodox form. These descriptions interested me, too, but for a different reason—I wanted to experience the region’s habitats and fishes myself. Some 30 years later, I was able to do so, but the landscape had changed significantly, and only a few of these habitats are still intact in South Sulawesi. There are now rice fields as far as the eye can see, and no stream remains unaffected. Nomorhamphus liemi from around Maros was described by Vogt (1978a) in honor of the exporter Liem Dig. A subspecies described later, Nomorhamphus liemi snijdersi (Vogt, 1978b), is now considered a synonym of N. liemi. N. liemi is quite variable. Depending on location, the beaks of the males can be deep black, crimson red, or a blend of both. The species is one of the smaller forms and reaches a maximum of about 3 inches (8 cm)

ALL: H.-G. EVERS

Breeding Dermogenys sp. “Malaulu” is difficult because the offspring gets progressively smaller from generation to generation—a common problem with all Dermogenys from Sulawesi.

for large females. I have tried and failed several times to find these fish, but they are still regularly exported. One local collector informed me that today the animals are caught further north, in the highlands near Palopo. He did not want to show me the places where he collects them. However, it is likely that the habitats here, like others in the highlands, are crystal-clear streams and rivers with slightly alkaline water, flowing hard over flat beds of stones and pebbles. Liem’s Halfbeak is peaceful and enduring in an aquarium. The females give birth to a maximum of about 10 very large juveniles (0.6–0.8 inch/1.5–2 cm). In my experience, adult females dropped babies three or four times before taking a break of up to a year, and then again produced fry several times. Thus, if you want to keep this species, you need to separate the females regularly. A swollen genital region identifies the pregnant females, which are best captured carefully with a very large net coming from below. Be sure to proceed with caution so as not to damage the sensitive beak or stress the animals too much! My birthing tanks for Nomorhamphus and Dermogenys hold about 8 gallons (30 L) and are densely planted. The females are fed well and generally drop their fry

early. In some species (Nomorhamphus rex, Nomorhamphus ebrardtii), waiting for the fry can become a game of patience. If you separate the females too early they may not give birth, or the young might be stillborn. Nomorhamphus liemi is certainly the most suitable species for the beginning breeder. Later you can try a different, more complicated species. Nomorhamphus brembachi

I caught Brembach’s Halfbeak only once in Bantimurung. Originally, the species was described by Vogt (1978b) from around Longrong, near the east coast of South Sulawesi. Today it is no longer worth the trip, unless you want to see more rice fields. Nomorhamphus ravnaki, its two subspecies N. r. ravnaki and N. r. australe, and N. sanusii (described by Brembach in 1991) are now considered synonyms of Nomorhamphus brembachi. N. brembachi and N. liemi males have a very pronounced black hook on the lower jaw. N. brembachi is quite variable in coloration, a trait it shares with N. ebrardtii from Sulawesi Tenggara, the southeastern part of Sulawesi. Nomorhamphus brembachi is encountered in the trade every now and then. I suspect that they are caught in

A pair of Nomorhamphus liemi, the best-known halfbeak of Sulawesi and a great “beginner’s halfbeak,” sometimes sold as the Celebes Halfbeak.

AMAZONAS 37

Orange-Finned Halfbeaks, Nomorhamphus ebrardtii, from Wolasi. These are males in normal coloration.

Bantimurung, because when we visited the national park we met some locals who told us that they occasionally catch fish there and sell them to a broker from Makassar to make a little extra money.

AMAZONAS

Nomorhamphus ebrardtii

38

By far the most common halfbeak exported from Sulawesi is Nomorhamphus ebrardtii. It was described from Sulawesi Tenggara quite early (Popta, 1912). My brother Frank, Jeffrey Christian of Maju Aquarium, and I were able to confirm the species in September 2009 in the area of Kendari, in the remaining intact rainforest near Wolasi. This region is densely populated, and it is only a matter of time before the last intact habitats will be trashed or

burned. From the plane we could see how little is left of the rainforest’s former beauty and could only imagine how it must have looked to the members of the Sunda expedition, which collected the fishes for the description. I know of four local variants, and they differ significantly in terms of color. The forms from Sulawesi Tenggara and the island of Muna are orange; those from Balambano are bright red. The morphs of Sulawesi Tenggara, at well over 4 inches (10 cm), are larger than the other known Nomorhamphus species. The form from Balambano is significantly smaller (about 3.2 inches/8 cm). We collected the morph from Wolasi at the end of the rainy season in residual water puddles (water temperature 89.6°F/32°C, 334 μS/cm). Beak, tail, and

ALL: H.-G. EVERS

Alpha male Nomorhamphus ebrardtii from Wolasi.

In these residual puddles near Wolasi, we caught large numbers of Nomorhamphus ebrardtii in 2009. The animals must survive several weeks, sometimes months, in these puddles until the rains arrive and fill the rivers again.

dorsal and anal fins are stained orange. Dominant males have an orange head cap and parts of the pectoral fins are also orange. We collected a second form in the Sumbersari waterfall near Wolasi, but at a higher elevation (75.7°F/24.3°C, 260 μS/cm). This form proved to be the most productive, with up to 30 juveniles per litter. Its color is similar to that of the first form, but the alpha animals lack their intensity. The front half of the caudal fin is orange, but the back half is transparent. Some animals of this form should still exist in the hobby, because I have distributed them to many friends. Both forms are living together with Oryzias sp. “Kendari,” a ricefish very similar to O. woworae, which was

described from the nearby island of Muna. On Muna, the most attractive and aggressive form of N. ebrardtii lives with O. woworae. The dominant males have a deep orange abdomen and are quite aggressive toward each other, even in large aquariums. The “beak wrestling” of adult males inevitably leads to the death of one of them. An effective way to curb the aggressiveness is to keep a large group. In an aquarium with an area of 60 x 24 inches (150 x 60 cm), I started with 10 wild-caught animals (half males, half females); only one male survived. I then added the first 20 fry, and later even more, and the deaths ended. In nature, N. ebrardtii not only hunts insects but also chases ricefish. I like to feed them large water beetles,

Male Nomorhamphus ebrardtii from the island of Muna have orange bellies and, like all forms of this species, bright neon-blue eyes.

AMAZONAS 39

AMAZONAS

Sungai Bantimurung in the karst mountains of the Maros highlands.

40

the deeper water regions, and also does this in the aquarwhich they catch and devour after a wild chase. Fishes ium. The little black devils quickly chased the N. ebrardtii up to the size of a male guppy disappear within a few through the large aquarium (60 x 24 x 20 inches/150 x seconds into the beaks of these hungry predators. The 60 x 50 cm) and made them stay just below the surface. form from Muna has been imported more than once and is still available from specialists. A surprise for us was the discovery of a red color form Nomorhamphus rex that I am lumping in with N. ebrardtii for now. (After all, Just recently, a species was described from South Sulawesi there is a whole mountain range between Sulawesi Tengthat has been imported from time to time. Huylebrouck gara and Sungai Balambano near the town of Malili.) et al. (2012) described Nomorhamphus rex based on fishes The neon-blue eyes, short beak, and especially the fin colcaught in Sungai Toletole and in the drainage of Sungai oration make it similar to N. ebrardtii, but the beak, abWewu. These rivers originate in the highlands west of domen, and unpaired fins are bright red, especially right Lake Matano and flow into Bone Bay. Much further east, after they are caught from the clear, fast-flowing stream and in Toraja, Jeffrey Christian, Peter Debold, and I were also confirming this species. The species settles in clear, (pH 8.0, 460 μS/cm, 14°dGH, 76°F/24.5°C). Sungai fast-flowing waters with temperatures between 74.3 and Balambano is regularly visited by aquarium fish collectors, so this form has probably made its way into the market by now. It is also the only river on Sulawesi where I encountered two syntopic halfbeaks A pair of Nomorhamphus ebrardtii below a waterfall in Sumbersari. sharing the same habitat in the same range. The second species is a smaller, black species. According to Kottelat et al. (1993), it is Nomorhamphus towoetii. I assumed at first that the larger N. ebrardtii would prevail as the dominant species in the aquarium. However, this was not the case. Nomorhamphus towoetii populated

The long lower jaw and the yellow pelvic and anal fins of the recently described Nomorhamphus rex from Central Sulawesi are unmistakable. This is a pair (male at the rear).

Nomorhamphus hageni

Popta (1912) also described Nomorhamphus hageni from Sulawesi Tenggara, a species that is a mystery to me. Meisner (2000) examined material from Penango (today Penanggo), a town north of the Menoke mountain range. I have not been there yet and therefore cannot write about this species. Whether or not the species is valid is questionable at the least. Since then no further specimens have been collected at the type locality, and the quality of preserved specimens is poor at best. Nomorhamphus kolonodalensis

To the north of the distribution of the above two species is the adjacent habitat of the Kolonodale Halfbeak. The species described by Meisner & Louie (2000) colonizes the region west of the port city of Kolonodale in the province of Sulawesi Tengah. In the immediate surroundings of the town, we Male Nomorhamphus ebrardtii from Muna “beak-wrestling.” found only swampy lowlands. Further south, in the hills of the Verbeekmas range (at the northern margin of Lake Matano), we discovered the species along with a new Telmatherina (Telmatherina sp. “Nuha”) near the village of Nuha. Sungai Suriya has fastflowing water with a pH of 7.2, 112 μS/cm, and a temperature of

AMAZONAS

ALL: H.-G. EVERS

77.7°F/23.5–25.4°C (slightly alkaline pH, electrical conductivity between 200 and 400 μS/cm). At first glance, N. rex is similar to its close relative N. ebrardtii, but it is smaller (males get up to 2.4 inches/6 cm, females about 3.2 inches/8 cm) and has a very long mandible (lower jaw) that is more than twice the length of the maxilla (upper jaw), particularly in males. The pelvic and anal fins of both sexes are yellow, and the posterior anal fin of males have black margins. The species is not very productive, and wild-caught animals in particular are initially problematic. Only in the F2 generation did the number of fry increase (up to 11 animals); all of them survived. Since the species is caught in Sulawesi on a regular basis as an aquarium fish, it is sometimes available in pet stores.

41

Nomorhamphus kolonodalensis has already been imported.

72.5°F (22.5°). Aquarium observations are not available because I did not bring any animals home. However, to my knowledge they were imported once or twice along with the Telmatherina.

AMAZONAS

The famous Saluopa waterfall is a tourist attraction and the habitat of Nomorhamphus celebensis, a black halfbeak.

42

The black Nomorhamphus The previous species were fairly simple, but it gets complicated now. The type species of the genus Nomorhamphus, N. celebensis, as well as N. towoetii and another very similar species available in the hobby (although its location is unknown), form a group of black halfbeaks worthy of taxonomic debate. Even the scientists are unable to agree and I am firmly convinced that something was mixed up in the revision of the genus by Meisner (2001). Nomorhamphus celebensis

As the type locality for Nomorhamphus celebensis, Mohr (cited by Brembach, 1991) mentioned Lake Poso as well as a river in “Lappa Kanru.” No halfbeaks live in Lake Poso, as Brembach reported, and I have not found any Nomorhamphus in the lake on my two trips (2008 and 2010). However, in the many rivers surrounding the lake lives a halfbeak that I would describe as N. celebensis. Meisner (2001) designated a lectotype with type locality “Lake Poso,” collected by the brothers Sarasin. Through the collections of Heiko Bleher and others in the early 1990s, and mine about 20 years later, we now know that N. celebensis is a river-dweller. In Sungai Saluopa, a tributary of the great Poso River in the north of the lake, beneath the famous waterfall of the same name, this species is the only fish found in the clear waters of the sinter terraces (pH 8.5, 236 μS/cm, 72°F/22.2°C). However, I was able to confirm it in many other places near the lake, down to Pendolo. N. celebensis likes it cool and suffers over time if the water temperature is above 77°F (25°C). Large females can be up to 4 inches (10 cm) long. The females are always gray, while the much smaller males adopt a charcoal

In the aquarium, Nomorhamphus celebensis is one of the most peaceful species that we know. Although the males display all day, they do not harm each other.

gray to deep black color when displaying. Irregular, light gray vertical bands and spots interrupt the uniformity. In an aquarium 40 inches (1 m) long or bigger, the males squabble constantly but harmlessly while the females look on. Everything remains relatively peaceful, and I have never observed “beak wrestling” or battle injuries. Large females give birth to more than 20 quite large fry (0.5–0.6 inch/1.2–1.5 cm). This species is relatively straightforward to care for and easy to breed.

Nomorhamphus celebensis under water, below the waterfall. The dark male is stalking the larger, light-colored females in the current.

Among the few aquarists who work intensely with halfbeaks, this species is a constant topic of discussion. In the hobby, a black halfbeak has been successfully maintained for several years, thanks to the efforts of Ulrike Korte and friends. This form is similar to the N. towoetii described by Ladiges (1972) from Lake Towuti, with respect to the small size (about 3.2 inches/8 cm for females and 2.4 inches/6 cm for males) and the relatively short beak. The black color is not mentioned in the description. This species definitely does not live in Lake Towuti. Kottelat (1989a/b, 1990) reported clearly about his expeditions to the Malili Lakes and also mentions the species described above: N. weberi for Lake Matano and N. megarrhamphus for Lake Towuti. He also rules out the occurrence of N. towoetii in Lake Towuti, but describes the species in fast-flowing streams “in some

places in the Malili basin” (Kottelat, 1990). He described males and females and mentioned the deep black color of displaying males. I suppose that because of Kottelat’s article, all black halfbeaks in the hobby came to be called N. towoetii, including the already imported N. celebensis near Lake Poso. This species is considerably larger and is much more peaceful than the little black hellions from Malili. The females of N. celebensis are light gray, while the females of N. towoetii can turn dark gray depending on mood. The form maintained by Ulrike Korte (2010) over many

AMAZONAS

ALL: H.-G. EVERS

Nomorhamphus towoetii

43

An aquarium strain of Nomorhamphus cf. towoetii from an unknown locality. Note the orange blotches on the rear of the males’ bodies and the brighter color of the female (above).

AMAZONAS

A pair of Nomorhamphus towoetii from Sungai Balambano near Malili. The females also turn dark during courtship.

44

Sungai Lawa is a cool, fast-running stream that flows into Lake Matano.

years is orange in the rear body area in both sexes, although the extent of the color varies individually. The females are always gray and do not turn dark. In addition, their halfbeaks are significantly shorter than those of the fish that Kottelat (1990) considers to be N. towoetii and which was caught in Sungai Balambano near Malili in September 2011 by Jeffrey Christian, Christian Reusch, and me. The species lives there together with a form of N. ebrardtii (see above). In the aquarium, the animals from Balambano are quite aggressive and even dominate the much larger N. ebrardtii. Husbandry has proved difficult and only a few young fish were produced (Reusch, pers. comm.). I could never discover the form cultivated by Korte on Sulawesi, despite intensive efforts. Because of their significant differences from N. towoetii (sensu Kottelat, 1990) I suggest that we call this fish Nomorhamphus cf. towoetii.

Undetermined Nomorhamphus In September 2011, during a trip I took to the Malili Lakes region with Jeffrey Christian and Christian Reusch, we collected three species of Nomorhamphus whose final determination is still pending. Nomorhamphus sp. “Sungai Lawa”

Before I left for Sulawesi, Fabian Herder of Bonn gave me a tip: search for halfbeaks in

AMAZONAS

ALL: H.-G. EVERS

Male Nomorhamphus sp. “Sungai Lawa”

45

Female Nomorhamphus sp. “Sungai Lawa”

46