The Christmas Double Issue

EVERY WEEK DECEMBER 14/21, 2022

9000

VOL

Megan, who previously worked at C OUNTRY L IFE , is a continuity and birth-centre midwife in a London NHS hospital and delivered her 100th baby on Christmas Day last year. She has a degree in Natural Sciences from Durham University and is now studying for a masters degree in Midwifery. Megan has also volunteered with Health & Hope, training midwives in remote Chin State, Myanmar, and is the daughter of Tim and Charlotte Jenkins of Esher, Surrey.

Photographed on West Wittering Beach, West Sussex, by Mike Garrard

Miss Megan Jenkins

Miss Megan Jenkins

CCXIX NO 50, DECEMBER 14/21, 2022

The Christmas Double Issue

This week

86 A time to give with love

The Revd Lucy Winkett offers her message of hope this Christmas

106 Paul O’Grady’s favourite painting

The actor, presenter and dog lover chooses a convivial Swedish scene

108 The ghost of a Christmas past

How do the preoccupations of 2022 compare with 1897?

110 Invincible to enemies

On the 950th anniversary of its royal transfer, John Goodall explores splendid and influential Lincoln Cathedral

120 All’s white with the world

Ice and snow consumed the painting world in the 16th century to create a pantheon of snowy masterpieces, says Michael Prodger

128 Hey, Mister Snowman

Katy Birchall selects her carrots and coals

132 The magic of Midnight Mass

The Revd Colin Heber-Percy sets his mind to the enchanted service on Christmas Eve

136 ’Tis the season to eat merrily

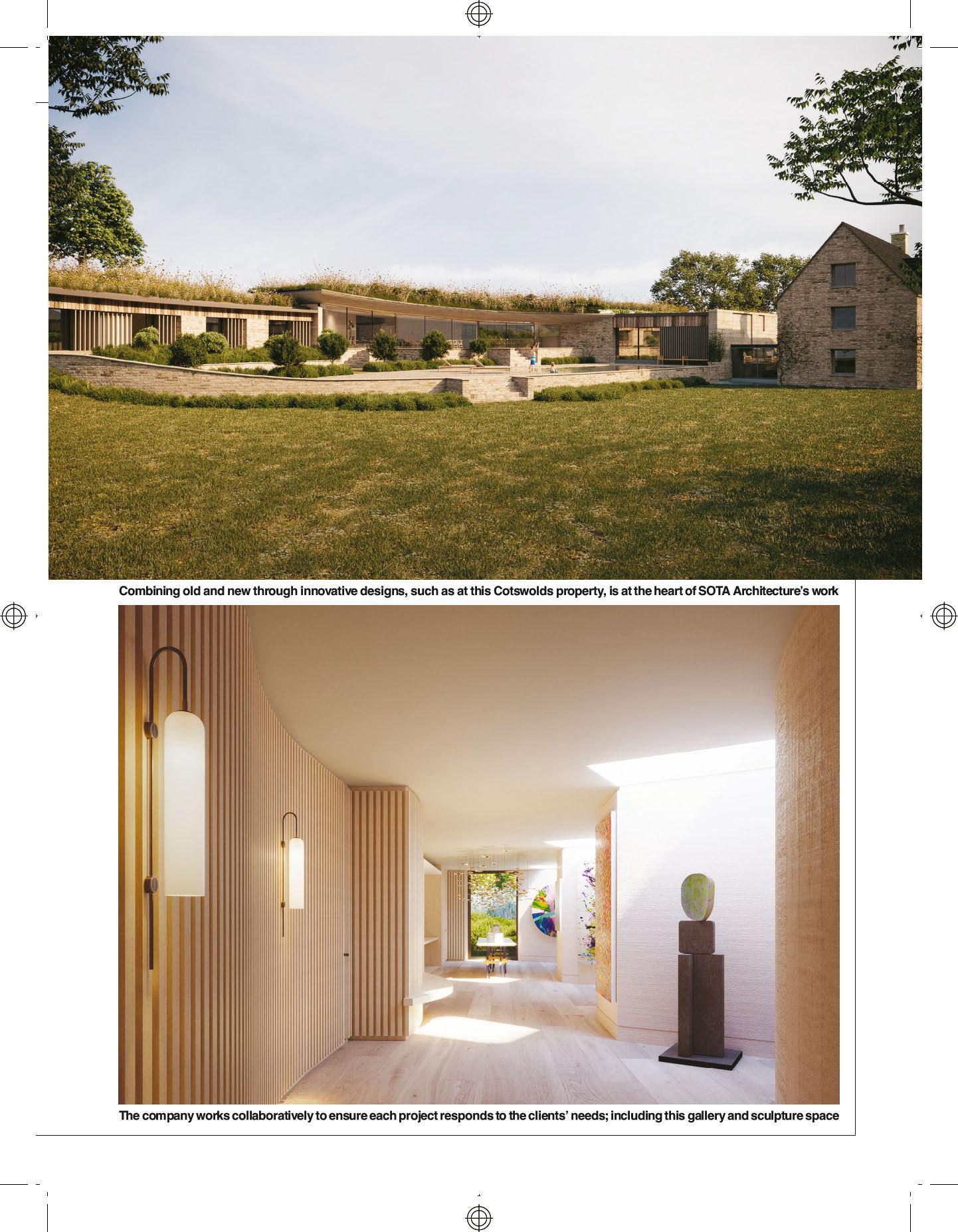

From the goose to the pudding, it’s worth getting the best for Christmas. Tom Parker Bowles presents his pick of the producers

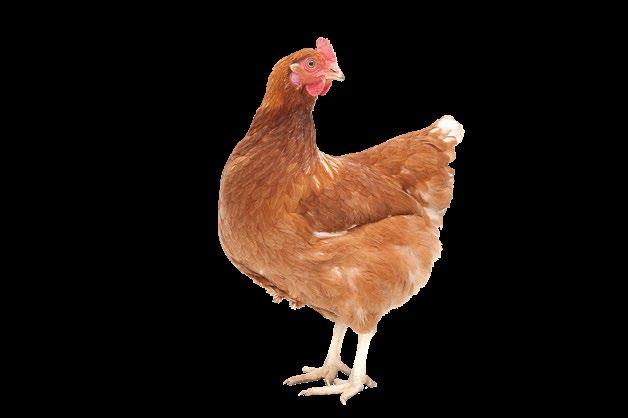

144 Pigs for Christmas—and for life

Could you eat your garden resident? Julie Harding talks to those who can and can’t

150 Of spice and men

The scent of the season is unmistakeable, but why are some spices so firmly associated with Christmas, asks Emma Hughes

156 Carve! The herald angels sing

Ben Lerwill meets woodcarver William Barsley, whose work echoes Westminster Hall

162 The master of disguise

If you manage to spot the well-camouflaged ptarmigan, you’re lucky, avers Simon Lester

166 A winter’s tale

Alexandra Wood remembers the frozen wonderland of a childhood power cut

168 The Editor’s Christmas Quiz

172 Plenty of room at the inn

As the snow falls, the villagers gather in the warm fug of the pub to welcome an early arrival, relates Kate Green

176 Put a ring on it

Once necessary, now ecofriendly, napkin rings are enjoying a revival, says Matthew Dennison

182 The golden goose

Succulent and tasty, it’s impossible to resist a juicy goose, finds Tom Parker Bowles

186 Interiors

Arabella Youens, Matthew Dennison and Amelia Thorpe wax lyrical about candles

194 Luxury

Last-minute treats, watches and diamonds to savour and Kit Kemp’s favourite things

206 One pine day

John Lewis-Stempel marvels at the pine cone, an edible example of Nature’s artistry

212 In the still of winter

Tiffany Daneff explores Fullers Mill, Suffolk, where plantsman Bernard Tickner created a remarkable garden from rough land

222 Bursting with life

Plant your bulbs and let the beauty unfurl, urges Stephen Desmond

228 Kitchen garden cook

Melanie Johnson tucks into Brussels sprouts

230 Gone rabbiting

Fiona Reynolds climbs

Watership Down in the pawprints of Hazel and Fiver

232 The verdict on 2022

Jamie Blackett looks back over a turbulent year from the sanity of his farm

Friend for life or supper? ( page 144 )

Contents December 14/21, 2022 EVERY WEEK DECEMBER 14/21, 2022 DECEMBER 14/21, 2022

Gold Hill, Shaftesbury, Dorset (Alan Morgan Photography/ Alamy)

Alamy; Getty; Look and Learn/Bridgeman

Images; William Barsley; Millie Pilkington/Country Life Pcture Library; John Holder

84 | Country Life | December 14/21, 2022

Left: Light up the night ( page 186). Above: All aboard with Mr Toad ( page 252)

234 The flying ghosts of Christmases past Jack Watkins salutes the magnificent equine heroes of the King George VI Chase

236 They wrote the words the whole world sings

First poems, now familiar carols, the likes of Hark! the herald angels sing often have unexpected origins, discovers Andrew Green

242 A coalition of interest

John Goodall talks to Sir Philip Rutnam, the erudite new chairman of the National Churches Trust, about the difficulties ahead

December 14/21, 2022 | Country Life | 85 Every week 94 Town & Country 100 Notebook 102 Letters 103 Agromenes 104 Athena 202 Properties of the week 220 In the garden 228 Kitchen garden cook 260 Art market 262 Books 266 The big crossword 268 Bridge/Quiz answers 270 Classified advertisements 280 Spectator 280 Tottering-by-Gently 246 Masterpiece Jack Watkins is swept away by Peter Pan 248 An Othello for the times Michael Billington reviews the theatrical year 252 All creatures great and small Animals in favourite childhood books stay with us forever, Another pint, please, and some of that stew ( page 172 ) Six issues for £6* Visit www.countrylifesubs.co.uk/X820 *After your first 6 issues, your payments will continue at £39.99 every three months. For full terms and conditions, visit www.countrylifesubs. co.uk/6for6terms. Offer closes January 31, 2023

Above: The elusive ptarmigan, striking in its monochrome winter garb ( page 162). Below: Angels from the realms of wood ( page 156)

A time to give with love

CHRISTMAS is one way that we measure the passage of time. It’s a punctuation moment in the year and we find ourselves remembering that it’s the first Christmas in this house or that it was the last Christmas with her or him. Nostalgia plays a large part in our celebrations as adults: it is a set of rituals to return to, which anchor us somehow, especially if the memories are happy ones.

In my role as Rector of St James’s Church, Piccadilly, in central London, I watch the run-up to Christmas take a particular turn each year. At the heart of the West End, our parish is full of bars, restaurants and shops, all advertising Christmas parties from October onwards. It was very odd being in central London during lockdown or restricted Christmases, when the lights were on and the decorations were up, but the streets were deserted. There was a special bleakness about the city during that time. If I’m honest, there hasn’t been a return to a pre-pandemic Christmas atmosphere, although the same lights and decorations are on this year. There are particularly spectacular angels that fly down Jermyn

Street and Piccadilly, but the crowds hurrying by underneath feel different: a bit more thoughtful somehow, less hedonistic and a little more, well, fragile.

As this year’s John Lewis television advertisement—with its focus on children in care—suggests, society is thinking about deeper themes, beyond the determination to have a good time.

I see much of this at St James’s. One of the striking moments of this winter was an

exchange we had in the run-up to the festive season. Every week, we host a hot meal in the church for people going through homelessness or on low incomes. It’s often a lively and chatty evening: the conversations I’ve had with our guests range from politics to history, music, family. One of the most animated was an argument about the 17th-century English Civil War and the merits (or otherwise) of the actions of Oliver Cromwell. As our Christopher Wren church

86 | Country Life | December 14/21, 2022

As many of us prepare to celebrate a simpler Christmas, the Revd Lucy Winkett is moved by the generosity of those often dealing with their own difficult circumstances and stresses that giving someone your time can be a great gift, too

Andrew Sydenham/Country Life Picture Library

Future Publishing Ltd, 121–141 Westbourne Terrace, Paddington, London W2 6JR 0330 390 6591; www.countrylife.co.uk

This is expressed in the birth of Christ, who showed us what God is like, but also what it could be like to be human

was consecrated in 1684, we were in the right place to be discussing the aftermath of the only 11 years of Republican rule that England has had and the debate went long into the evening.

Another time, we were collecting donations for our local food bank, when one of our homeless guests turned up with an offering. I am ashamed to say that I was rather too surprised that this had happened. Really, I shouldn’t have been: people are generous and kind, despite strikingly difficult circumstances. Yet this was such a remarkable gesture, I felt humbled by it. It was a moving example of gift-giving that put all my prospective shopping to shame. Of course, I want to live in a city that has neither food banks, nor people sleeping on the streets. But at a time of great hardship for many and great anxiety for most, this impulse to give a gift to someone else moved me beyond words.

This is one of the ways in which I think that the message of Christmas makes sense in a secularised society. For Christians, the celebration focuses on the astonishing gift that God gives: of life itself, of wonder and miracle, light and hope. This is expressed in the birth of Christ: a unique and irreplaceable human life who showed us what God is like, but also, perhaps more challengingly, showed us what it could be like to be human. I think that within all human

Property Magazine of the Year 2022, Property Press Awards

PPA Magazine Brand of the Year 2019

PPA Front Cover of the Year 2018

British Society of Magazine Editors Columnist of the Year (Special Interest) 2016

British Society of Magazine Editors Scoop of the Year 2015/16

PPA Specialist Consumer Magazine of the Year 2014/15

British Society of Magazine Editors Innovation of the Year 2014/15

beings, practising Christian or not, there is the deep impulse to give. Not only to buy presents, but to give, sometimes, ourselves, our time, our love or our commitment. It’s implanted deep within us as part of what human beings do.

these concerns are also shaping the way we shop and give at Christmas. The younger generations can see that a throwaway culture harms the planet—single-use plastic or fast-fashion goods may raise eyebrows if unwrapped on Christmas Day.

It’s also affecting our approach to work, particularly among younger people who appear to seek demonstrable purpose— especially social purpose—in their jobs, as I recently found out at a meeting with business leaders. Attention to environmental and modern-day-slavery issues among today’s corporations is notably strong and

Six issues for £6*

Visit www.countrylifesubs.co.uk/X820

*After your first six issues, your payments will continue at £39.99 every three months. For full terms and conditions, visit www.countrylifesubs.co.uk/6for6terms

Offer closes January 31, 2023

But raising these concerns doesn’t have to reduce the fun or dampen the celebrations. Staple gifts of soap, tea, candles, clothes, jewellery, books and electronic gadgets can all be kind to people and the planet, if chosen carefully. Perhaps, therefore, this Christmas might be a simpler, more thoughtful one, expressing the sort of empathy and imagination that was shown by our homeless guest, not only for other people, but for the Earth, and making every gift, however simple, more beautiful, because it’s given with love.

The Revd Lucy Winkett is the Rector of St James’s Church, Piccadilly, London W1. Formerly a professional soprano, she is a long-standing contributor to ‘Thought for the Day’ on BBC Radio 4’s ‘Today’ . The church is raising funds to repair and re-use its buildings in an environmentally sensitive way, honouring its post-war history, as well as adapting, re-landscaping, celebrating and cherishing the historic green space and architectural heritage. To donate to the St James’s Wren Project, visit www. sjp.org.uk/donate/the-wren-project

Editorial Editor-in-Chief

Mark Hedges

Editorial Enquiries

Editor’s PA/Editorial Assistant

Amie Elizabeth White 6102

Telephone numbers are

prefixed by 0330 390

Emails are

name.surname@futurenet.com

Deputy Editor Kate Green 4171

Managing & Features Editor

Paula Lester 6426

Architectural Editor John Goodall

Gardens Editor Tiffany Daneff 6115

Executive Editor and Interiors

Giles Kime 6047

Acting Deputy Features Editor

Carla Passino

Acting News & Property Editor

James Fisher 4058

Lifestyle and Travel Editor Rosie Paterson 6591

Luxury Editor Hetty Lintell 07984 178307

Commercial director Clare Dove

Advertisement director Kate Barnfield 07817 629935

Advertising (Property) Julia Laurence 07971 923054

Lucy Khosla 07583 106990

Luxury Katie Ruocco 07929 364909 Interiors/Travel Emma Hiley 07581 009998

Art & Antiques Mollie Prince 07581 010002

Classified Tabitha Tully 07391 402205 Millie Filleul 07752 462160

Advertising and Classified Production Stephen Turner 6613

Senior Ad Production Manager Jo Crosby 6204

Inserts Canopy Media 020–7611 8151; lindsay@canopymedia.co.uk

Back issues www.magazinesdirect.com

To find out more, contact us at licensing@futurenet.com or view our available content at www.futurecontenthub.com

December 14/21, 2022 | Country Life | 87

Head of Print Licensing Rachel Shaw Circulation Manager Matthew De Lima Production Group Production Manager Nigel Davies Management Senior Vice President Women’s, Homes and Country Sophie Wybrew-Bond Managing Director Chris Kerwin Please send feature pitches to countrylife.features@futurenet.com Printed by Walstead UK Subscription delays We rely on various delivery companies to get your magazine to you, many of which continue to be affected by Covid. We kindly ask that you allow seven days before contacting us about a late delivery at help@magazinesdirect.com Head of Design Dean Usher Senior Art Editor Emma Earnshaw Deputy Art Editor Heather Clark Senior Designer Ben Harris Picture Editor Lucy Ford 4072 Deputy Picture Editor Emily Anderson 6488 Chief Sub-Editor Octavia Pollock 6605 Senior Sub-Editor Stuart Martel Digital Editor Toby Keel Property Correspondent Penny Churchill Country Life Picture Library Content & Permissions Executive Cindie Johnston 6538 Subscription enquiries 0330 333 1120 www.magazinesdirect.com

human

Within all

beings, Christian or not, there is the deep impulse to give

Town & Country

Edited by James Fisher

One foot forward, one back

ADECISION to open a new coal mine in Cumbria has been described as an ‘incomprehensible act of self harm’. The comments, made by Sir David King, head of the Climate Crisis Advisory Group, have been echoed by scientists, campaigners and institutions both at home and abroad as fury mounts over the decision taken last week. Green MP Caroline Lucas called the decision a ‘climate crime against humanity’, as Cumbrian Liberal Democrat MP Tim Farron simply described it as ‘daft’. Frank Bainimarama, the prime minister of Fiji, added: ‘Is this the future we fought for under the Glasgow pact?’

The outrage comes after the Levelling Up Secretary Michael Gove signed off on the plans last Wednesday, which will see the first coal mine opened in the UK in 30 years. The plan will see an investment of some £165 million and is projected to create 500 jobs in the area. The mine will produce up to 2.8 million tons of coking coal a year, which is used in steel-making. The project was initially proposed in 2014, and received local and Government backing in 2020 and 2021, respectively, before having consent withdrawn in the run up to COP26 in Glasgow in November last year.

Mr Gove approved the mine on the basis that ‘there is currently a UK and European market for the coal’ and that the carbon emissions produced ‘would be relatively neutral and not significant’. The department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities said that the decision to approve the mine was in line with the Government’s commitments to reduce carbon emissions. It is expected to be operational until 2049, one year before the UK has pledged to reach carbon ‘net zero’. Sir Jake Berry, Conservative MP for Rossendale and Darwen in Lancashire, agreed that the decision to open the mine was ‘good news for the North and for common sense’.

Not all in the Conservative party agreed, with Tory peer Lord Deben, chairman of the Government’s advisory Climate Change Committee (CCC), calling the proposal ‘absolutely indefensible’. Conservative MP Philip Dunne, chair of the environmental audit committee, said: ‘Coal is the most polluting energy source and is not consistent with the Government’s net-zero ambitions. It is not clear cut to suggest that having a coal mine producing coking coal for steel-making on our doorstep will reduce steelmakers’ demand for imported coal.’ Conservative Alok Sharma, president of COP26, added that ‘over the past three years

the UK has sought to persuade other nations to consign coal to history, because we are fighting to limit global warming to 1.5˚C and coal is the most polluting energy source. A decision to open a new coal mine would send completely the wrong message and be an own goal.’

Critics have said justification for the mine is flawed, pointing out that most of the coal extracted will be exported. The two companies that still produce steel in the UK—British Steel and Tata—have said they plan to move away from using coking coal. Labour has said it would prevent the opening of the mine if elected; it is also expected that the decision (to open the mine) will be challenged in court.

The decision comes in the same week that the Government decided to relax restrictions on building on-shore windfarms in England, after some 30 Conservative MPs threatened to rebel against a planning bill. The decision will see a change to a 2015 law that only allowed for on-shore windfarms to be built in very specific areas, leading to a sharp decline in on-shore wind in recent years, with critics saying it was effectively a ban. The decision also fell under the remit of Mr Gove, who said local authorities would have the ability to identify sites suitable for on-shore wind. New farms would still be subject to local approval.

94 | Country Life | December 14/21, 2022

On-shore windfarms, such as this one in Wales, may become more common, but a new coal mine in Cumbria has also been approved

Alamy; Val Corbett

Tower of trouble

PLANS have been submitted to renovate London’s Liverpool Street station, but have met resistance from campaigners such as the Victorian Society (VS), SAVE Britain’s Heritage and the C20 Society. The plans, designed by architects Herzog & de Meuron, will see the station upgraded to a ‘modern transportation hub’, with two new structures that will house offices and a hotel. The plans are up for public consultation.

The VS says the plans ‘would irreparably damage [the station’s] character and architectural and historical significance’. It is urging the public to engage with the consultation and to object. The society also intends to resurrect the Liverpool Street Station Campaign, which successfully prevented the demolition of the building in the 1970s.

Last week, the listing status of the station was upgraded by Historic England, much to the

jubilation of the campaigners opposing the plans. The new listing, updated from 1975, takes into account the redevelopment of the concourse in the 1990s by architect Nick Derbyshire.

‘This “consultation” gives no opportunity to consider less harmful options and uses images that misleadingly “greys out” the huge tower above the station to make it semi-transparent,’ says Joe O’Connell, director of the VS. ‘Rather than a sensitive response to listed buildings in a conservation area, the proposals appear to be an attempt

Garden goodwill

THENational Garden Scheme (NGS) has donated some £3.11 million to its beneficiary charities this year, as visitor numbers and openings bounced back after the pandemic. The majority (£2.45 million) went to nursing and health beneficiaries, such as Marie Curie, Macmillan and Hospice UK, and the rest was spread among garden charities. For the first time in its history, the NGS is supporting English Heritage’s Historic and Botanic Garden Training Programme, too, with a commitment of £125,000 this year.

‘Despite the worst of the pandemic having passed, our beneficiaries continue to support those in often dire need and who have now been confronted with the challenge of the cost-of-living crisis,’ says NGS chairman Rupert Tyler. ‘This continues to place unbearable pressure on many aspects of their work and we are delighted to continue our support in such a meaningful way.’

Chief executive George Plumptre adds: ‘The enormous contribution by our garden owners and volunteers was added to by other fundraising activities. A special event at the iconic Temperate House at Kew raised more than £48,000 and, in

Good week for Wildcats

The woodlands of Devon and Cornwall have been pitched as suitable loca tions for the reintroduction of the European wildcat in England. The species became extinct in the 16th century and is the UK’s rarest mammal, living only in remote parts of Scotland

Spoonbills

proving divisive

to maximise commercial return by creating a shopping centre dressed up as publicamenity space over the station.’

In response, developers say the £1.5 billion scheme will not harm the station and called the concerns based on ‘misconceptions and misunderstandings’. James Sellar, CEO of developers Sellar said the current experience of Liverpool Street was ‘woeful’. ‘There is no reason I can see why London wouldn’t want to embrace the opportunity’. Those behind the plans added that ‘not a single Victorian bolt will be touched’.

A record 77 young from 43 pairs of spoonbills was recorded by the RSPB and Natural England this year, with breeding pairs and colonies now in eight locations across the UK as landowners improve wetland habitats and tree cover

David Croc-ney

The 85-year-old artist delighted The King with his ‘beautifully chosen yellow galoshes’ at the Order of Merit luncheon. Mr Hockney paired his brightly coloured crocs with blue socks and his signature checked suit for the occasion

Bad week for Hooved thespians

Live horses will no longer feature in the Metropolitan Opera’s produc tion of Aida, ending a 30-year tradition. The board-treading equines will be replaced by a digital background on the New York stage in May

Lights out in Lewis’s John Lewis and Waitrose are turning down thermostats and dimming lights to bring energy bills down. The retailer predicts it will overspend on its energy budget by £18m

Saltaire ‘stain’

July, we hosted our third Great British Garden Party, giving the opportunity for anyone—whether they open their garden or not—to hold an event with friends or family... generating £30,000.’

The NGS is hosting a Christmas raffle, which is open until December 20. There are 15 prizes, including a luxury day visit for two to The Newt in Somerset, an online consultation about your garden with Chelsea Gold-winning partners Hugo Bugg and Charlotte Harris and a signed copy of Arabella Lennox-Boyd’s Gardens in My Life. Tickets cost £5; visit www.ngs.org.uk to enter.

Proposals for a new visitor centre in Saltaire, West Yorkshire, have met a backlash from residents, who claim the £5.39m modern building would be a ‘stain’ on the UNESCO World Heritage Victorian village Solar from the Sahara

An £18bn project to link Britain to a wind and solar farm in the Sahara, hoped to provide 8% of Britain’s electricity supplies by 2030, has been delayed by at least a year due to political turmoil AEW

December 14/21, 2022 | Country Life | 95 For all the latest news, visit countrylife.co.uk

Low Crag, Cumbria, opened for the NGS in June

Plans to renovate Liverpool Street station are

Town & Country

A pair of CyberMen guard the entrance to the National Museum of Scotland last week, in preparation for the ‘Doctor Who Worlds of Wonder’ exhibition. The touring exhibition opened at the Edinburgh museum on Friday and explores the science behind the hit television series. Visitors can expect everything from contributions by the specialists who bring the show to life to iconic monsters, gadgets and props

We need right trees, right place

AFRESH approach to tree planting is needed to safeguard our woodlands against climate change, says Sir William Worsley, chair of the Forestry Commission, as new figures reveal the full extent of the damage caused by storms across Britain last winter.

Sir William suggests that woodland owners should be encouraged to plant and manage more diverse and resilient forests of varying ages and species of trees to mitigate stronger gales, drought, pests and diseases, as well as more frequent severe weather events.

Forest Research-led mapping has revealed that almost 31,506 acres of trees were lost in storms last winter in Britain, with some 22,980 acres of damage in Scotland and 8,278 acres across England. The main culprit was Storm Arwen, an extra-tropical cyclone that blew across Britain overnight on November 26–27, 2021, accounting for 30,055 acres of tree loss.

Although it is estimated that more than 90% of trees felled as a result of storm damage will be replanted, Sir William is calling for a rethink on how that work is carried out to ensure the long-term prosperity of our woodlands. ‘The figures highlight the challenges we are facing with a changing climate and more frequent and extreme storm events,’ he points out. ‘The woodlands of the future need to be planted and managed differently if they are to not only survive,

Storm Arwen toppled dozens of trees in November 2021, as in John Muir Country Park, East Lothian

but thrive. Now and in the long term, we need a wider range of tree species and age profiles across the country. This targeted approach will ensure the long-term resilience of our precious woodlands.’ He notes: ‘At a national scale, the level of loss is comparatively modest, but the loss of trees can also have a devastating impact on individual woodland owners and we continue to support the forestry sector and partners with their recovery from winter storms.’ SM

96 | Country Life | December 14/21, 2022

Town & Country

Flowers flock together

A‘COOPERATIVE nurseries stand’

is to make its debut at the RHS Chelsea Flower Show, it has been announced. The idea, which is the brainchild of the Plant Fairs Roadshow (PFR), will see eight nurseries share a single stand at the prestigious horticultural show, in a bid to ‘share the load’ and introduce new growers to the world-famous event. The 107sq ft stand will be divided up into eight segments for individual nurseries to design and showcase their speciality plants, with a central information hub manned by specialists.

The PFR is made up of a ‘diverse collective’ of some 40 nurseries from across the South of England. ‘We are really delighted to have been allocated a place at Chelsea,’ said Colin Moat of Pineview Plants in Kent, who is also the PFR committee chair. ‘Eight of our nurseries will work

together to showcase a diverse range from house plants, to maples, shadeloving and sun-loving to perennials and bulbs too; all in one area.’

The PFR was set up 10 years ago and its cooperative ethos has allowed the group to grow in size and stature, according to Mr Moat. With the increased cost of energy and raw materials, that collective ambition is more important than ever, he adds. As well as Chelsea, the PFR intends to go on a 13-date ‘tour’ of some of the best castles, museums and gardens in 2023.

‘The RHS seem very keen to get new blood coming through—none of us is getting any younger (I put myself in that category),’ adds Mr Moat. ‘It’s good to have youth and enthusiasm supported in this way so they can showcase their unique and interesting nurseries for the first time on the world stage of the Chelsea Flower Show.’

Country Mouse

Lit up like a large Christmas tree

ALTHOUGH I failed to pick the holly before the birds had eaten all the glistening red berries, I have been busy preparing for the first Christmas in our new house. In fact, the preparations began almost two years ago, when I asked our architect to make the hall double height, mainly so that we could have an enormous Christmas tree. I love Christmas and everything that goes with it. I always tell everyone that Christmas lunch is little more than a Sunday roast and that I don’t understand what the fuss is all about, then I do exactly the opposite.

It is the time for fuss and family, carols and candles, tradition and thanks. Every family has its own ways. This year, the Christmas message will be from the new King, but, for most families, little else will change.

I am already preparing for future Christmases. After the decorations have been brought down on Twelfth Night, I will take the mistletoe into the orchard and, with my trusty penknife, cut small notches into the branches of the apple trees, before squeezing the pearl-like white seeds into them. In time, I will have my own mistletoe and feel even more self-sufficient.

Happy Christmas to you all. MH

Town Mouse Christmas merriment

THE children have been as eager as ever to decorate the house for Christmas, but the character of their enthusiasm has undergone a distinct teenage inflection. In years gone by, excitement made them over eager to help, tangling the lights and attempting to install baubles far beyond their reach. Now, their engagement is more theoretical. Therefore, although there was a keen demand for a Christmas tree, when it was proposed we should go and collect it, they were quick to excuse themselves. One declared themselves exhausted and the other, with more tactical ingenuity, despaired volubly of homework commitments.

In return, I made it clear that the Christmas tree would not appear miraculously and I wasn’t collecting it alone. A short debate later, we set off in slightly quarrelsome mood. Tempers improved, however, during the selection process and, soon afterwards, I hoisted the chosen tree on my shoulder. For some reason, the spectacle struck the children as hilariously funny. On the walk home, they behaved like a couple of paparazzi running around taking photographs on their phones, which they shared with family and friends. Unable to think of a practical way that they could help, I was obliged to suffer their merriment. Next year, I thought grimly, I might get the tree alone after all. JG

98 | Country Life | December 14/21, 2022

The light trail at Windsor Great Park, Berkshire, awes visitors in the run up to Christmas. Part of the Windsor Great Park Illuminated festival, the light trail features 18 installations around the park’s obelisk pond. The festival is open until January 2, 2023; tickets start at £11 for children

Town & Country Notebook

Quiz of the week

1) In ’Twas the Night Before Christmas, what does St Nicholas hold in his teeth?

2) The writer and composer of Silent Night hailed from which European country?

3) Which three British mammals enter true hibernation in winter?

4) What’s the original Latin name of Oh Come, All Ye Faithful?

5) What are the last five words of A Christmas Carol?

Word of the week

100 years ago in December 23, 1922

Paws for thought

Dog trainer Ben Randall offers his advice

Life in the fast lane

Edited by Carla Passino

IT is very pleasant to see the country relatives landing at the terminal stations, coming from distant parts, many of them carrying what we presume to be game or poultry in canvas bags and others with great bunches of redberried holly, which this year has done its best to provide with plenty of colour. If one may judge from their happy faces, they come with a determination to make the most of a brief visit to town… Between the staff of a newspaper and its readers the connection never can be so intimate, yet in the course of a quarter of a century we have come to know one another far more closely than those outside would think possible… It is, therefore, in no merely conventional spirit that in this year of grace we wish to each and every reader a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year.

QI have an eight-month-old Patterdale terrier who wants to run after traffic all the time. I can’t let him off the lead, unless I am far away from the roads—please can you offer me any advice?

L.P., via email

ASeeing your puppy running after traffic can be terrifying. Here’s how to stop him:

1. Use meal times to build patience. Have him sit in a controlled area with his food— it’s the first building block in teaching him to wait patiently in all environments. 2. Make recall a positive experience. On hearing the

Time to buy

command, he must understand that something good is happening around you. 3. ‘Leave’ means ‘leave’ in any situation. Your dog needs to know that, when the command is given, a form of reward will come his way. 4. Build trust through ‘heel’. If your dog is taught that staying close to your side is a positive experience, he will soon learn to trust you and your commands.

5. Don’t allow your dog too much freedom on walks, as this can encourage the chasing.

6. Beware of inadvertently ingraining bad habits. If you’re throwing a ball five times on every walk, three times a day, that’s roughly 450 times a month that you’ve encouraged your dog to chase after a moving object. To pose your own canine conundrum, email paws-for-thought@futurenet.com. For details about Mr Randall and his training app, visit www.gundog.app/trial

The Mill on the Floss,

Riddle me this

It should belong to a foot, but now hangs off a chimneypiece. What is it?

100 | Country Life | December 14/21, 2022

1) The stump of a pipe 2) Austria

3) Hedgehogs, dormice and bats

4) ‘Adeste Fideles’ 5) God bless us, every one Riddle me this: A Christmas stocking

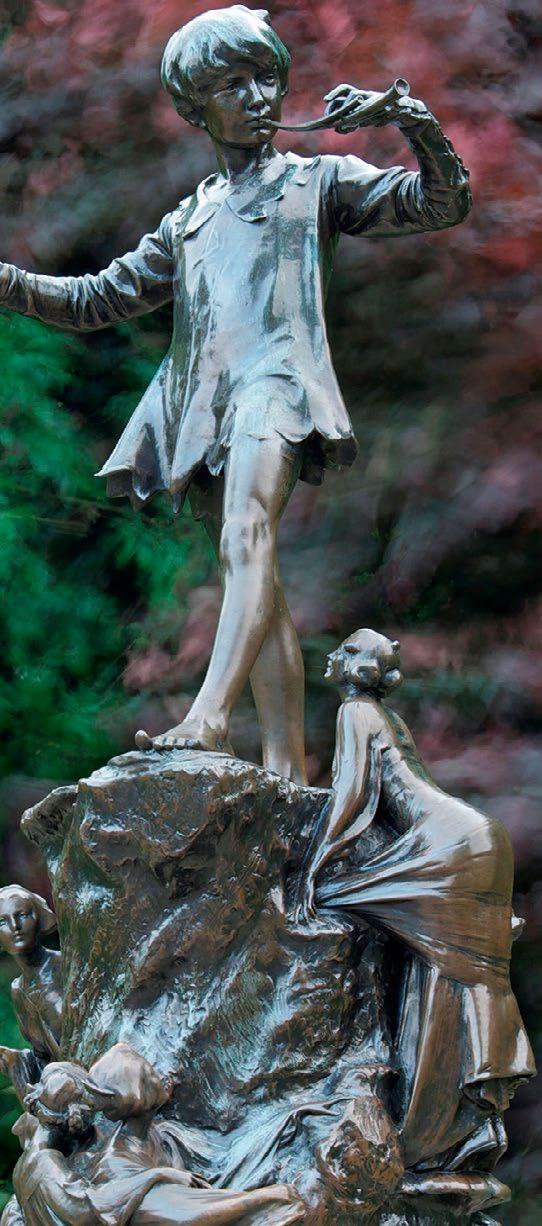

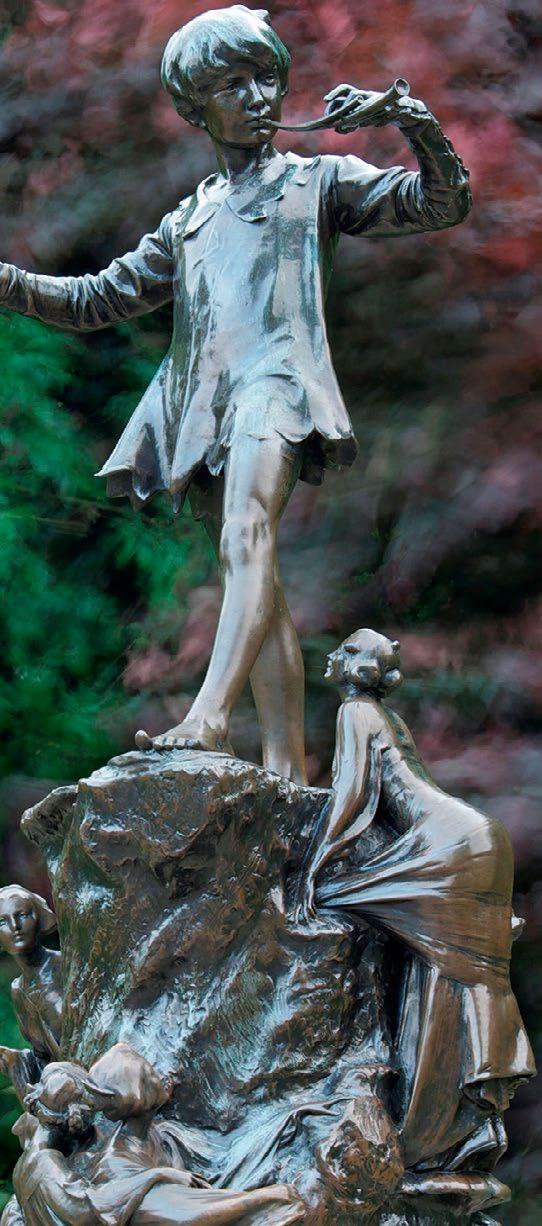

‘Fine old Christmas, with the snowy hair and ruddy face, had done his duty that year in the noblest fashion, and had set off his rich gifts of warmth and colour with all the heightening contrast of frost and snow’

George Eliot

Apolaustic (adjective) Devoted to enjoyment

Lady Jane leather gloves, £49.95, Barbour (www. barbour.com)

Angela Harding Rose Cottage 1,000-piece jigsaw puzzle, £15, National Trust (https:// shop.nationaltrust.org.uk)

Grosvenor hamper, £250, Claridge’s (www. shop.claridges.co.uk)

In the spotlight Woodcock (Scolopax rusticola)

Wines of the week

Easy does it

Lidl, Crémant de Loire Brut, Loire, France, NV. £8.49, Lidl, alc 12%

Crémant is a good hunting ground for value fizz and this doesn’t disappoint. This uncomplicated, traditionalmethod sparkler from the Loire is a light, aperitif-style wine, with green apple fruit and toastiness. Chenin Blanc-dominated, with some Chardonnay.

Fit for Dionysus

Santo Wines, Selection

Cuvée Assyrtiko, Santorini, Greece, 2018. £18.95 Aspris & Son, alc 13.2%

Its plumage is a marbled miracle, as complex as Venetian paper in shades of cocoa, hazel, sepia, chestnut, tawny, khaki and buff. A perfect match, then, for the moulding leaves and twiggery of the woodland floor— and all the better for lying low in the light of day. Should you disturb one, up it will shoot, dodging through the trees, but not far, settling again into leafy obscurity.

Largely nocturnal and elusive, heading for marshes under cover of darkness, woodcock, the enigmatic collective noun for which is a ‘fall’, are year-round residents, but increase

Unmissable events

Until January 1, 2023

Christmas at Stourhead, Stourhead, near Mere, Wiltshire

Giant baubles, tunnels of lights and the mesmerising fire garden transform Stourhead into a winter wonderland (01747 841152; www.nationaltrust. org.uk/stourhead)

Until January 8, 2023 Christmas at Chatsworth, Bakewell, Derbyshire. Inspired by Nordic traditions, celebrations combine an installation of giant Finnish decorations with a massive ice wall laced with carvings, a pine forest in the Sculpture Gallery and folklore tales (01246 565300; www.chatsworth.org)

Did you know?

in number each winter, when the home birds are joined by visitors from colder parts of the Continent. Similarly timed arrivals of goldcrests gave the latter the moniker of ‘woodcock pilot’ (Notebook, November 16). The tiny goldcrests were thought to hitch a ride on the backs of the sturdier wader to get across the North Sea. Had somebody, somewhere, seen it happen? Perhaps, or they thought so, as woodcock hens may carry their chicks to safety when danger threatens. Certainly, migrant woodcock are prepared to hitch a ride on passing ships.

Made with 100% Assyrtiko, this has a fragrant nose of lanolin and peach, plus a pinch of citrus and flint. The 2018 vintage now showcases lovely depth on the bone-dry palate, with acacia honey-scented stone fruits, refreshed by lime zest. Ripe melon notes lead to a long and fulfilling finish. A perfect partner for shellfish in a creamy sauce or simply fish and chips.

Wake up and smell the rosé

Domaine Montrose, 1701, Côtes de Thongue, Languedoc, France, 2020.

£19.35 Vinvm, alc 13.5%

Until January 15, 2023 ‘Dutch Flowers’, Compton Verney, Warwickshire. This touring exhibition, in partnership with the National Gallery, explores Dutch flower paintings ( pictured )

from their early-17th-century beginnings to their late-18thcentury heyday (01926 645500; www.comptonverney.org.uk)

Until February 25, 2023 ‘Gordon Rushmer: A World in Watercolour’, Petersfield Museum and Art Gallery, Petersfield, Hampshire. A selection of work by the Petersfield-born artist (01730 262601; www. petersfieldmuseum.co.uk)

December 22–23 Carols by Candlelight, Salisbury Cathedral, Salisbury, Wiltshire. The premiere of a new carol by composer Errollyn Wallen (01722 555148; www.salisbury cathedral.org.uk)

Linear freshness, intense citrus zing and lingering wildstrawberry and pink-grapefruit notes. Delivers more than your average rosé: great definition, a strong mineral backbone and a nuttiness from partial ageing in oak. Elegant and enjoyable.

Drinking pretty

Kumeu River, Village Pinot Noir, North Island, New Zealand, 2021. £11.50, The Wine Society, alc 13%

Like biting into a ripe red cherry, this wild-fermented, unoaked Pinot emphasises youthful sweet prettiness, but is kept from being confected by fresh raspberry acidity, sappy fruit tannins and a savoury, leafy edge.

For more, visit www.decanter.com

Men could get their beards shaved in the middle of the frozen Thames during London’s first recorded frost fair in 1608. Between then and 1814, the capital would go on to have seven more big fairs, as well as many smaller ones. Charles II attended in January 1684—his ticket is now at the Museum of London.

December 14/21, 2022 | Country Life | 101

Getty; Alamy; Paulus Theodorus van Brussel, Flowers in a Vase /The National Gallery, London

Letters to the Editor Mark Hedges

Letter of the week

Clever boots

YOUR article on John Lobb (‘If the shoes fit’, November 23) brings to mind my late grandfather, James Stuart Farrer. He was discharged from the army in 1917 with the rank of private, a full disability pension and a badly damaged leg that required a surgical boot. By the mid 1920s, he was sufficiently affluent to have his shoes handmade by Lobbs, which improved his mobility and made his disability less obvious. Some 50 years later, an eagle-eyed government official spotted that, despite his pension being paid, my grandfather had made no claim for any new surgical footwear. Someone was dispatched to check he was still alive and enquire why he had not presented himself for any footwear; after he explained, it was decided it would be more cost effective for him to continue having his shoes made by Lobbs. Sadly, he died before he could claim his first pair of free handmade shoes. Our family has speculated whether this was a unique occurrence or if others had the same experience. It certainly caused amusement for everyone. I did contact Lobbs to ask if we could have his lasts, but, unfortunately, I was too late as they had been destroyed. Jane Anthony, via email

The writer of the letter of the week will win a bottle of Pol Roger Brut Réserve Champagne

I see your true colour

ONreading ‘The 39 Steps’ in the recent issue of GENTLEMAN’S L IFE (November 2), I would like to take exception to point 12, namely that ‘a gentleman would never wear Wellington boots that aren’t black or olive green’. Although I do have a green pair for shooting, I often find myself wearing yellow RNLI Wellington boots as part of our PPE. I question whether that precludes us from being gentlemen, or indeed ladies, when fulfilling our duties.

Graham A. F. Hill, via email

Time to get real IN

tackling the menace of plastic waste, Agromenes (November 30) advocates stopping building wasteto-energy plants and creating a really efficient recycling system instead. Sadly, in the real world, this is a contradiction in terms. Really efficient recycling can only take place when the recycled product has a value greater than the cost of recycling and much of the plastic that is polluting the world’s oceans started life in some well-meaning person’s recycling bin. The solution is to minimise waste production, maximise economic recycling and then incinerate the rest in a waste-to-energy plant. Timothy Palmer, Wiltshire

All fired up

OH , but there are pub log fires to be had in Mumbles (Letters, November 16 )! On a recent weekend, I visited my daughter there and, on Sunday, we went to church together. After the service, a group of us (including the minister and his wife)—goodnaturedly referred to as ‘The God Squad’—walked the few steps to The Woodman, on the seafront. There, we were welcomed by a gloriously flaming and spluttering log fire. It warmed the cockles of this old lady’s heart—as well as her fingers.

Yvonne Bell, Somerset

Yvonne Bell, Somerset

A right royal delicacy

IENJOYED Tom Parker Bowles’s celebration of that crowning glory of the clubland table, the robust savoury (‘Strong Flavours to Savour, November 23), but I was disappointed by the omission of eggs Drumkilbo. This delicious dish consists of lobster claw and tail meat, chopped up with either hardboiled hen’s eggs or quail’s eggs and skinless tomato, served in a glass with a mayonnaise and Worcestershire sauce, usually topped with a large prawn and

parsley. It is occasionally served at my club (usually as a starter) and was— according to legend—a favourite of the late Queen Mother, who liked to have sherry added to the sauce. Christopher Goulding, Newcastle-upon-Tyne

Contact us (photographs welcome)

Email: countrylife.letters@futurenet.com

Post: COUNTRY LIFE , 121–141, Westbourne Terrace, Paddington, London, W2 6JR

We regret that we are unable to respond to letters submitted by post Future Publishing reserves the right to edit and to reuse in any format or medium submissions to the letters page of Country Life

N.B. If you wish to contact us about your subscription, including regarding changes of address, please telephone Magazines Direct on 0330 333 1120

Country Life, ISSN 0045-8856, is published weekly by Future Publishing Limited, Quay House, The Ambury, Bath, BA1 1UA, United Kingdom. Country Life Subscriptions: For enquiries and orders, please email: help@magazinesdirect.com, alternatively from the UK call: 0330 333 1120, overseas call: + 44 330 333 1120 (Lines are open Monday–Saturday, 8am- 6pm GMT excluding Bank Holidays). One year full subscription rates: 1 Year (51) issues. UK £213.70; Europe/Eire €380 (delivery 3–5 days); USA $460 (delivery 5–12 days); Rest of World £359 (delivery 5–7 days). Periodicals postage paid at Brooklyn NY 11256. US Postmaster: Send address changes to Country Life, Airfreight and mailing in the USA by agent named WN Shipping USA, 165–15, 146th Avenue, 2nd Floor, Jamaica, NY 11434, USA. Subscription records are maintained at Future Publishing Ltd, Rockwood House, 9–16, Perrymount Road, Haywards Heath, RH16 3DH. Air Business Ltd is acting as our mailing agent. BACK NUMBERS Subject to availability, issues from the past three weeks are available from www.magazinesdirect.com. Subscriptions queries: 0330 333 1120. If you have difficulty in obtaining Country Life from your newsagent, please contact us on 0330 390 6591. We regret we cannot be liable for the safe custody or return of any solicited or unsolicited material, whether typescripts, photographs, transparencies, artwork or computer discs. COUNTRY LIFE PICTURE LIBRARY: Articles and images published in this and previous issues are available, subject to copyright, from the Country Life Picture Library: 01252 555090/2/3.

Editorial Complaints: We work hard to achieve the highest standards of editorial content and we are committed to complying with the Editors’ Code of Practice (https://www.ipso.co.uk/IPSO/cop.html) as enforced by IPSO. If you have a complaint about our editorial content, you can email us at complaints@futurenet.com or write to Complaints Manager, Future Publishing Limited Legal Department, 3rd Floor, Marsh Wall, London E14 9AP. Please provide details of the material you are complaining about and explain your complaint by reference to the Editors’ Code. We will try to acknowledge your complaint within five working days and we aim to correct substantial errors as soon as possible.

102 | Country Life | December 14/21, 2022

John Lobb; Alamy; Getty

Still your guns

THE recent correspondence in C OUNTRY L IFE about not shooting woodcock (Letters, November 30) highlights the precarious state of the species’s population in this country, both migrant and indigenous. Game shooters were encouraged not to shoot the birds until December 1, despite them being in season from September 1. This ambiguity is flawed and does little for the future survival of a threatened species. Perhaps all shoots should be asked to remove woodcock from their quarry lists for a period of two, possibly three years and monitor populations during that time?

Delicious to eat they may be, but, unless some more positive restraint on shooting them is imposed, woodcock may not grace people’s plates for much longer.

Michael Brook, North Yorkshire

Boars become bores

IN Felixstowe, Suffolk, our major container port, there’s a campaign under way that should help to protect farmers all over the country. Two years ago, Agromenes warned that the spread of African Swine Fever threatens the whole of the pig industry, counselling tougher measures on meat imports and a much more effective slaughter policy aimed at our growing wildboar population. The Forestry Commission and Defra upped their game partly as a result.

Every Continental country is battling against the disease, which is passed on by live animals and infected meat. Tourists often innocently import meat that has not been produced to the high EU standards, but, at Felixstowe, Defra’s Animal and Plant Health Agency and the UK Border Force are after the commercial businesses that evade food-standards controls to send uncertified meat into Britain.

DECEMBER 28

We present our Grand Tour of Britain, 52 places to visit and admire. Plus, snipe shooting in Devon, fine topiary and the last in our series examining the English home

Make your week, every week, with a Country Life subscription 0330 333 1120

The cost-of-living crisis means that unscrupulous traders are on the lookout for cheaper products. Safety isn’t their first concern. In two weeks, more than 300kg of illegal meat has been seized in Felixstowe and the Port of Harwich, Essex. It doesn’t sound a lot, but you don’t need much infected material to start an outbreak, which is why Defra has recently tightened the rules for all travellers entering this country.

Brexit hasn’t helped co-operation with the rest of Europe and, in a world where we know that diseases in plants and animals will increase, we must have coordinated policies. We really have to get over our post-referendum obsession with doing things differently. The UK Food Standards Agency (FSA) has been told that, instead of having sensible policies, it must rewrite all the regulations that were patiently worked out when we were members of the EU—whether they need change or not. Hundreds of pages of rules will be replaced

by hundreds of pages of new rules—merely so we can say they’re not EU rules.

For goodness’ sake, change rules that aren’t working, but don’t change them for the sake of change, simply to satisfy the dogmatists. The FSA has a huge job on its hands protecting us without this enormous amount of unnecessary work. It needs to be concentrating on the essentials, including the threat of animal diseases, of which African Swine Fever is only one. That demands its continuing efforts, together with Defra, the Port Health Authorities and the Forestry Commission.

We also need media support, so Agromenes was pleased to see the Daily Telegraph highlighting the battle against wild boar in Spain, Germany and Italy. Sadly, it hardly mentioned the British problem, suggesting that only Scotland was ‘worth keeping an eye on’ —no reference to the many areas of England where wild boar is rampant.

Chronic underfunding and fear of animal-rights protesters mean Britain has had no really effective slaughter policy and the wild-boar population has grown out of control. Two litters a year, with four or more piglets a time, mean that only constant culling works. Otherwise, we will soon have the kind of urban issues that they have in Barcelona, where boar have learned to feed off the easy pickings of food-wasting humans.

That threat ought not to be the driving force, however. It is the urban domination of Government policy and our metropolitan media that forces us to warn of trouble in our cities to get any real attention in the countryside. Yet that’s where the problem is now. The livelihood of pig farmers, already threatened by the import of pork and bacon from countries with lower welfare and safety standards, is at risk from African Swine Fever. This should be a priority for Defra—the Department for Rural Affairs.

December 14/21, 2022 | Country Life | 103

Chronic underfunding and fear of animalrights protesters mean we have no effective policy

Athena Cultural Crusader

Hoping for a Christmas miracle

MORE of Athena’s readers— believers or not—will visit a church at Christmas than at any other time of year. If they do so, they will surely be aware that the future of these buildings is under renewed threat. Not only do they face intense financial pressures but also the likelihood of a further decline in congregations; a recent survey of the Office of National Statistics revealed that just under half the population now identifies as Christian. There are two groups concerned with the future of historic churches to whom this news of decline will not, perhaps, be entirely unwelcome. One is Christians for whom these buildings and their contents are perceived as a burden. They want the church to be about people not places or things.

They see churches as strictly functional buildings for praying in and, if they can no longer serve that purpose, then they are superfluous and their costs, complexities and lack of modern amenities can justifiably be made someone else’s problem.

quality of churches as places set apart. Historic churches transcend time and offer a welcome vacuum in a world where everything else has a purpose and a timetable. For the same reasons, to those who care for them, they offer a sense of place and belonging. That’s something we need to preserve.

At the same time, there are those who value ancient churches for the beauty and history they enshrine, but are indifferent to their religious use. In their eyes, a church without a congregation can be converted to other, secular functions that respect the fabric, perhaps post offices or libraries. The claim is that such uses will secure the physical survival of these public buildings in a post-religious world.

Athena understands these views, but is out of sympathy with the imperative of function that underpins both of them. At heart, that’s because they fail to recognise the crucial

She also distrusts the confidence of those who advocate solutions conceived in the abstract to a group of buildings that are themselves so varied in form, circumstance and location. After all, the converse of belief is not disbelief, but doubt, a quality both underrated and in short supply. It may also be a luxury. Although, therefore, she admits that there are no easy answers as to how these buildings can survive, it strikes her that one certain route to disaster would be to pursue a coherently planned or centrally imposed reorganisation. Instead, they need to be allowed to muddle on.

Finally, Athena regards our historic churches fundamentally as monuments to the human condition. As such, she sees them less as the preserve of secular or religious interest, than as buildings that naturally amplify both qualities when desired. Indeed, for whatever reason you attend a service this year, you are—miraculously—drawing on their richness in both regards and adding depth to them as well.

The way we were Photographs from the C ountry L ife archive

1898Published

Luddington, Warwickshire, photographed by Charles Latham for the first book published by the COUNTRY LIFE press, The Shakespeare Country. The view is carefully composed around the curve of the road. Washing hangs out to dry, a child sits in his perambulator and elms, now vanished from our landscape, rise in the distance.

Every week for the past 125 years, COUNTRY LIFE has documented and photographed many walks of life in Britain. More than 80,000 of the images are available for syndication or purchase in digital format. To view the archives, visit www. countrylifeimages.co.uk and email enquiries to licensing@ futurenet.com

104 | Country Life | December 14/21, 2022

Country

Life Picture Library

One certain route to disaster would be to pursue a centrally planned or imposed reorganisation

My favourite painting Paul O’Grady

Breakfast in the Open by Carl Larsson

Paul O’Grady is a comedian, actor and the presenter of ITV’s Paul O’Grady: For the Love of Dogs. His children’s book Eddie Albert and the Amazing Animal Gang: The Curse of the Smugglers’ Treasure is out now

I like paintings that stir the imagination and this one does. The ladies fuss over a table, as a maid unpacks a hamper, puppy in attendance. A young man watches. I get the impression that he’s annoyed. Perhaps he’s hungry and tired of waiting for his breakfast; perhaps the hatless young woman standing next to him is his wife and they’ve had a row. What is the old lady with a stick cooking in that cauldron? Porridge? Boiled eggs? Water for tea? The young girl leaning against the tree seems lost in thought. Is she simply enjoying the musicians or dreaming of true love? Judging by her expression, they’re happy thoughts. I love the light and the perspective and, looking again, I wonder if they’ve eaten and are, in fact, packing up. As I said, it awakens the imagination

Charlotte Mullins comments on Breakfast in the Open

AYOUNG woman in a white dress loops her arms around a slender birch tree and gazes away from a family gathering. She is Lisbeth, aged 19, fourth child of the artists Carl Larsson and Karin Bergöö. Karin can be seen through the trees, tending the fire, as Lisbeth’s sisters Brita and Suzanne chat over a table laid for an alfresco breakfast. Their brother Pontus snoozes under his straw hat in a chair nearby, as a group of travelling musicians serenades the family. The scene is taking place in 1910 on an island opposite the family home—a cottage in Sundborn, 140 miles northwest of Stockholm in Sweden—that can be seen in the distance.

Carl Larsson spent 10 years at art school in the 1860s and 1870s. He supported himself as an illustrator and his limpid style owes

much to his early employment. He went on to paint many murals for Swedish buildings, including the Stockholm Opera House and the National-museum, inspired by the bold lines of Japanese prints and the fluidity of Art Nouveau.

This large oil painting, Breakfast in the Open, now in the Norrköpings Konstmuseum in Sweden, completed in 1913, followed a largescale study he painted during the summer of 1910. The Larsson family originally only spent their summers in the Sundborn cottage, but, from 1901, they relocated there, refurbishing the house with Karin’s textiles. Their relaxed, family-centred life, with its picnics and boating trips, was idealised in Larsson’s paintings.

The house in the background, called Lilla Hyttnäs, is now the Carl Larsson-gården museum.

106 | Country Life | December 14/21, 2022

Breakfast in the Open, 1913, oil on canvas, 78in by 160in, by Carl Larsson (1855–1919), Norrköpings Konstmuseum, Sweden

Alamy

The ghost of a Christmas past

We compare the Victorian Christmas of 1897, the year of COUNTRY LIFE’s founding, with present-day festivities

1897

Queen Victoria retreats to Osborne

Advent calendar

Homemade Christmas card

Stamp costs 1d

Stir-up Sunday

Goose club

Swags on fireplace

Log fire

Decorations on Christmas Eve

Fir tree

Candles on Christmas trees

Penny toys

Eggnog

Wassail punch

Tate newly opened

Sugar plums

Orange and walnuts in stocking toe

Stilton

Cheddar

Fried smelts

Christmas lunch for the poor

Love came down at Christmas

Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde

Snapdragon

Rudyard Kipling

Nine Lessons and Carols at Truro

Cravat

Embroidered lavender bag

Tobacco pouch

Sleeping cap COUNTRY LIFE

2022

Charles III’s first Christmas message

Chocolate Advent calendar

E-card

First-class stamp costs 95p

Waitrose delivery

Avian flu

Free-standing woodburner

Bioethanol fire

Oxford Street on November 2

Non-drop tree

Candles around the bath

Baubles from Liberty

Champagne

Mulled wine

Cézanne at Tate Britain

Hotel Chocolat

Terry’s Chocolate orange

Stilton

Cheddar with cranberries

Smoked salmon

Crisis at Christmas

All I want for Christmas is You

Beauty and the Beast

Ibble dibble

Michael Morpurgo

Carols at King’s

Christmas jumper

Scented candle

Vape

Beanie COUNTRY LIFE

Alamy; Getty

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Invincible to enemies

The Cathedral of the Blessed Virgin, Lincoln

On the 950th anniversary of its royal transfer, John Goodall looks at the medieval development of one of Europe’s most brilliantly conceived cathedrals

Photographs by Paul Highnam

IN 1066, a well-born monk of Fécamp called Remigius supplied a ship and 20 knights to William, Duke of Normandy, as he prepared to assert his claim to the English throne by force of arms. Remigius sailed with the Norman fleet that autumn and was present at William’s victory at the Battle of Hastings. Reward for his support came the following year, when he was granted the first diocese to fall vacant in England. This had its cathedral church at Dorchester-on-Thames, Oxfordshire, and enjoyed authority over a vast swathe of territory that extended north to the Humber.

Remigius’s appointment was mired in scandal, but it would prove hugely significant. In 1072, as part of the far-reaching reform and reorganisation of the English church, he was commanded by the King—acting with the advice of the Pope—to transfer his cathedral church to Lincoln at the opposite geographical extreme of his diocese. At the time, Lincoln was one of the largest and most populous settlements in England, strategically positioned where the River Witham cuts through the limestone ridge that extends up the eastern side of the kingdom.

The medieval city of Lincoln occupied the site of a Roman settlement that had begun life as a fort in about AD 60. It stood at the

December 14/21, 2022 | Country Life | 111

Fig 1: The cathedral nave. Its far-spaced and slender piers allow expansive views

junction of two major thoroughfares, Ermine Street, which ran along the ridge and connected London to York, and Fosse Way, which began in Exeter. Between AD85 and AD 95, the fort became a self-governing city for veterans, a colonia, known as Lindum. In the process, it expanded and spilled down the steep escarpment of the ridge to form two rectangular, fortified enclosures, now the Upper and Lower City, with suburbs beyond.

The medieval re-occupation and revival of Lincoln was a combined consequence of its position on the Roman road network and command of the Witham, a river gateway to England from the east coast. On both counts, the city was crucial to William the Conqueror’s attempt to subdue the north of England, with its close Scandinavian connections. In 1068, he established a castle here, one in a series that was destructively intruded during his first northern campaign into towns along Ermine Street at York and Huntingdon and—connected to it—at Cambridge.

At Lincoln, the entire Upper City became the bailey or ‘Bail’ of the castle and the Domesday Survey of 1086 records the associated loss of 166 properties. It was evidently as a reinforcement of this castle that

Remigius transferred the seat of his diocese to the city in 1072. The bishop assumed an explicitly military role in the city, where he owed the very considerable service of 45 knights to the castle, and secured a building site for the cathedral within the Bail. The latter was located on the lip of the escarpment in the next-door corner to the artificial mound or motte of the castle.

Work to the new church probably began in about 1075 and was almost complete at Remigius’s death in 1092. It was, in the

words of the chronicler Henry of Huntingdon, writing in about 1130, ‘a strong church in that strong place, a beautiful church in that beautiful place… both agreeable to the servants of God and also, as suited the times, invincible to enemies’. The emphasis on defence is borne out by what survives of the building today: a huge triple arch fossilised in the west front with openings for dropping missiles above the main doors (Fig 3) .

The design is evocative of a Roman triumphal arch and is constructed throughout

112 | Country Life | December 14/21, 2022

Fig 2: The Exchequer Gate to the close. Three spires once rose from the towers

A strong church in that strong place, a beautiful church in that beautiful place

using cut blocks of masonry, a mark of the most ambitious 11th-century architecture. How this structure related to the cruciform plan of Remigius’s cathedral remains a matter of debate. It could be that, as today, it formed a screen façade to the nave. Alternatively, it might have formed part of a tower either attached to the nave or even freestanding from it, like a keep. Whatever the case, it otherwise bears technical comparison to

Byzantine churches, such as the slightly later west front of St Mark’s in Venice, Italy.

Many English cathedrals after the Norman Conquest—including Canterbury, Durham and Worcester—doubled as monastic churches. At Lincoln, by contrast, Remigius’s foundation was organised after Continental example, as a so-called ‘secular’ cathedral. That is to say, it was not served by monks, but by a community of canons or priests

with individual incomes. The canons needed a chapter house to meet and discuss business, but there was no requirement for communal monastic buildings and their houses were spread around a gated close (Fig 2) that expanded piecemeal beyond the line of the Roman wall.

In 1140, during the civil war known as the Anarchy, Lincoln Cathedral was briefly converted into a castle by King Stephen and,

December 14/21, 2022 | Country Life | 113

Fig 3: The 11th-century triumphal triple arch and later frieze fossilised in the west front. Note the central gallery of seated kings

following his defeat at the Battle of Lincoln on February 2, 1141, possibly sacked and burnt. Thereafter, it was rebuilt by the Bishop, Alexander, so that—again in the words of Henry of Huntingdon—‘it appeared more beautiful than in its original state, and would not yield to the fabric of any other building in England’. Among other changes, he is credited with vaulting the whole length of the building in stone.

Possibly as part of Bishop Alexander’s aggrandisement of the church, a frieze of sculpture depicting scenes from the Last Judgement and Old Testament was created across the west front. It is the only major figurative cycle of its kind to survive in England and, over the past 40 years, has been partly boxed in for protection. This year,

however—as part of a wider restoration project and the creation of new visitor facilities made possible by the National Heritage Lottery Fund—the whole frieze has been revealed once again, with replica figures pieced in where necessary. Examination of the sculpture shows that it was originally painted.

On April 15, 1185, the cathedral was badly damaged by an earthquake and, the following year, a new bishop was unanimously elected by the chapter, a Carthusian monk and Burgundian nobleman, Hugh of Avalon. The two events marked a turning point in the history of the building. Bishop Hugh was a formidable figure equally admired by kings and the poor (although his English was, apparently, not good). Famously, his saintly presence calmed the temper of a particularly

large and fierce swan at his Lincolnshire manor of Stow and the bird became his emblem. Hugh was involved in efforts to rebuild the damaged cathedral and the choir, where the work began in 1191, is named after him. The designing mason was intimately familiar with the new Gothic east end at Canterbury Cathedral, recently renewed as the setting for the shrine of the murdered Archbishop Thomas Becket. From Canterbury, he took inspiration for the technical detail and planning of the choir at Lincoln, which included two pairs of transepts and a terminating shrine chapel beyond the high altar. The chapel was almost certainly intended for the body of Bishop Remigius, whose unimpressive case for sanctity—in the absence of alternatives—was then being promoted.

The design of St Hugh’s Choir is a distinctively English exploration of the Gothic idiom at fundamental odds with its ultimate sources in France. In place of the soaring height of such 1190s cathedral designs as Chartres or Bourges, the vaults at Lincoln are both relatively low and low sprung; in contrast with the French High Gothic use of windows to screen the structure of the building from the interior, Lincoln proudly displays its massive walls and encrusts them with carved detail; and, instead of a design in which each vertical bay of the building is discretely conceived and uniform, Lincoln delights in visual integration, syncopation and variety.

Nowhere is this playful ingenuity more clearly apparent than in the vaulting of the choir. Canterbury makes use of vaults divided by ribs into six compartments spread over two bays. At Lincoln, however, the mason compressed the same six-part form over each bay in order to enrich the architectural effect. The resulting asymmetric pattern, which also incorporates a longitudinal rib running along the apex of the vault, is so completely out of character with the logic of French design that it has been memorably dubbed the ‘crazy vault’ (Fig 5)

Crazy or not, the vault was refined and regularised when the rebuilding work continued into the nave during the 1220s—after the violent interruption of the The Fair of Lincoln in 1217 (C OUNTRY L IFE , January 11, 2017 ), during which the cathedral was

114 | Country Life | December 14/21, 2022

Fig 4 above: The magnificent east window. The window above lights the roof space.

Fig 5 facing page: St Hugh’s Choir, with its crazy vault and 14th-century choir stalls

The pattern is so out of character with the logic of French design that it has been dubbed the “crazy vault”

plundered. Here, after its example, the number of ribs on the surface of the vault was increased and the visual distinction between the structural bays further blurred. The result is an unprecedented density of ornament and a strong horizontal emphasis that carries the eye through the length of the interior. Further accentuating the effect are the broad nave bays, which create clear views from the central vessel into the aisles (Fig 1)

Architectural ideas from Lincoln were widely copied, a clear mark of medieval admiration. Remarkably, their influence also extended outside England. Particularly intriguing is Lincoln’s influence in the Baltic at Trondheim Cathedral, Norway, and— possibly—on the vaulting of the Cistercian church at Pelplin, Poland.

With the completion of the nave—and the repair of the crossing following the collapse of the central tower in 1237—attention returned to the east end of the church. In 1220, after working miracles from beyond the grave, Bishop Hugh was canonised and Remigius’s claims to sanctity were forgotten. To create a sufficiently splendid setting for

Hugh’s two shrines—one for his body and another for his head—royal licence was sought to extend his choir across the wall of the Bail to the east of the church in 1255. Adjacent to the extension is a magnificent chapter house on a polygonal plan begun in about 1200 (Fig 10) . It opens off the cloister of the 1290s (Fig 9) .

St Hugh’s Choir determined the proportions of the extension, known as the Angel

Choir. The new work, however, borrowed ideas from the extravagant rebuilding of Westminster Abbey by Henry III (C OUNTRY L IFE , December 15/22, 2021). From Westminster, for example, came the eponymous figures of angels, which are carved in the upper registers of the walls (Fig 7 ), and the ornamentation of windows with lattices of stone termed bar tracery. The stupendous eight-part window that today terminates the Angel Choir interior was of unprecedented size (Fig 4)

Covering the whole structure of the cathedral, and easily forgotten, is a magnificent series of steeply pitched roofs. This monumental and dramatic roofscape, inspired by Continental example, was originally further enlivened by three spires, two over the west end and a third, rising over 500ft (that at Salisbury in Wiltshire scrapes 400ft), added to the central tower when it was raised to its present height in the early 14th century. The spires have all since been lost or dismantled, the principal being the first to come down after a storm in January 1548.

The medieval cathedral was richly furnished both inside and out with monuments

116 | Country Life | December 14/21, 2022

Fig 6 above: The Judgement Portal, flanked by chapels. Fig 7 below: Sumptuous carving and polychrome masonry in the Angel Choir

and figurative sculpture of superlative quality. Important survivals include a 14th-century gallery of Kings, the Judgement Portal (Fig 6), a series of chantry chapels attached to the aisles of the Angel Choir, the pulpitum screen and also a sepulchre used in the Easter liturgy with figures of sleeping soldiers. Another important fragmentary survival is the shrine of Little St Hugh (Fig 8), a boy said to have been crucified by Jews in 1255. His story and shrine are sobering testimony to the violent antisemitism in England that preceded the expulsion of the Jews by Edward I. The shrine never subsequently attracted much devotion and was only destroyed in the 17th century, probably in 1644.

The stupendous eight-part window in the Angel Choir was of unprecedented size

Because of its constitution as a secular cathedral, Lincoln was less affected by the Reformation than its monastic peers. It was, nevertheless, transformed liturgically, physically and institutionally by the religious changes that ensued. Neither these, however, nor the major restoration campaigns that have punctuated its more recent history, have compromised the grandeur, interest or integrity of its architecture. Indeed, even in European terms, Lincoln remains an outstanding structure, remarkable for the ambition, interest and ingenuity of every stage in its evolving design. Few buildings have remained so consistently admired for so long.

Visit www.lincolncathedral.com

December 14/21, 2022 | Country Life | 117

Fig 8 above left: The shrine of Little St Hugh, which was damaged in the 17th century. Fig 9 above right: The cloister of the 1290s. Fig 10 below: The polygonal chapter house was begun in about 1200. A view from the vestibule, which was roofed in 1216

All’s white with the world

It was a 16th-century change in climate that prompted painters to experiment with re-creating a snowy-white world, often through judicious use of colour. Michael Prodger reveals how some of the best-loved wintry artworks came into being

122 | Country Life | December 14/21, 2022

Alamy; The Fine Art Society, London, UK/Bridgeman Images; Musée Condé, Chantilly /Bridgeman Images

WHAT does the Grindelwald Fluctuation have to do with Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s muchloved 1565 painting The Hunters in the Snow, the winter scene that, over the years, has graced countless Christmas cards and Advent calendars? Or with the flurry of Dutch 17th-century canvases showing jolly burghers skating—and tumbling—on frozen canals? Or the paintings of the London frost fairs, which saw tented villages pop up on the icy Thames and the river turn into a slippery theme park? Or another seasonal greetingcard staple, Henry Raeburn’s portrait of the 1790s showing the Revd Robert Walker skating gracefully and determinedly across a Scottish loch? The answer is that, without the Grindelwald Fluctuation, they might well have never been painted.

It is the name given to a period during the ‘Little Ice Age’, when the world’s glaciers began to expand. Starting in about 1560, it marked a point at which the thermostat was turned down on much of northern Europe, not to be dialled up again until the mid 19th century. Although there was nothing new about snow and ice, during this period they became regular and prolonged features in

everyone’s lives. No wonder then that painters began to add the chilly white world to their repertoire: climate change affects art, too.

The sub-zero world was not much in evidence in art until the early 16th century, not least because there was no established genre of landscape painting. There were, of course, exceptions, such as a manuscript illustration of about 1525–30 for the Persian epic poem

Shahnama (Book of Kings), which shows the hero Isfandiyar’s troops struggling to put up their tents in a snowstorm, watched by placid dromedaries and horses with their teeth chattering. The 12th-century Chinese painter Li Gongnian depicted a bleak and bare winter landscape and his 14th-century compatriot Yao Yanqing showed snow-covered mountains.

In Western art, snow first fell in the miniatures made for the Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry, a sumptuous book illustrated by the Burgundian Limbourg brothers between 1412 and 1416. In their miniature for the month of February, they combine a series of snowbound scenes: a man cuts down a tree for firewood as another drives a log-laden donkey off to the nearby town; sheep are tucked up in a snow-covered pen in front of a line of beehives with an icy coating; a smallholder, blowing on his hands, approaches a thatched dwelling (obligingly left open-sided by the painter so we can see within), where two women and a man sit in front of a fire, their tunics unashamedly hitched up to defrost their naked nether regions. It is not only the cockles of their hearts that are warming and the image must have made the Duke of Berry chuckle in the midst of his devotions.

It was Bruegel who became the first artist to explore the potential of snow systematically. As well as his picture of hunters returning, he painted the first Western scene with falling snow, The Adoration of the Kings in the

December 14/21, 2022 | Country Life | 123

There was nothing new about snow and ice, but they became prolonged features in everyone’s lives

Preceding pages: Winter Landscape with Skaters and Bird Trap, 1565, by Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Facing page: The Reverend Robert Walker Skating on Duddingston Loch, 1790s, by Henry Raeburn. Above: Halstead Road in Snow, 1935, by Eric Ravilious

Bleak and bare indeed: ancient trees in Winter Landscape by Caspar David Friedrich

Room for irreverence: spot the peasants lifting their clothes in the February page from the Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry, 1412–16, by the Limbourg Brothers

Snow (Epiphany) of 1563, which transposes the birth of Christ to a Flemish village, as well as other Biblical scenes, such as the Nativity, the Census and, in multiple versions, the Massacre of the Innocents. It was one of his snow scenes, Winter Landscape With Skaters and Bird Trap (1565), that started the fad for winter pictures across the Low Countries.

Bruegel’s painting of a snowbound rural village with children playing on a frozen river was adapted by subsequent painters to show variations of frolicking citizens of both town and country. The most avid purveyor of this new genre was Hendrick Avercamp, born in Amsterdam in about 1585, who enlivened his pictures with vivid detail: among his promenaders, skaters and ice golfers, he painted a man relieving himself, the bare buttocks of a fallen skater pointing skywards, canoodlers finding the cold no restraint on their ardour. All of human life was there. Avercamp was born a deaf mute—‘de Stomme van Kampen’ (the mute of Kampen)—and his affliction heightened his amused observation of his fellow citizens. As snow changed the physical world, so his condition, too, set him apart.

By the early 19th century and the Romantic period, painters were treating snow less as

The two sides of the season