Journal of Medical Sciences and Health

DOI: 10.46347/jmsh.2021.v07i01.016

Year: 2021, Volume: 7, Issue: 1, Pages: 91-94

Case Report

R Manjula1, Sandhya Lakshmy Menon2, C Ranjitha2

1Professor, Department of Anaesthesiology, Adichunchanagiri Institute of Medical Sciences, Mandya, Karnataka, India,

2Postgraduate Student, Department of Anaesthesiology, Adichunchanagiri Institute of Medical Sciences, Mandya, Karnataka, India

Address for correspondence:

Dr. R Manjula, Professor, Department of Anaesthesiology, Adichunchanagiri Institute of Medical Sciences, B.G. Nagara: 571448, Nagamangala Taluk, Mandya district, Karnataka, India. Phone: +91-9008706071. E-mail: [email protected]

Carotid body tumours (CBT) are considered rare. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice and poses many anaesthetic challenges especially in large tumours. In this paper we present our experience of anaesthetic management of CBT excision since very few cases have been reported so far. Preoperative planning and multiple contingency plans to ensure secure airway, cerebral protection, mange haemodynamic fluctuation are utmost important. A high degree of vigilance should be continued in the postoperative period to detect stroke or identify other cranial nerve deficits. With a team approach to management of CBT, operative complications can be minimized with a good outcome.

KEY WORDS:Carotid body tumor, catecholamine surge, chemoreceptor cells, non-chromaffin paraganglioma, hypotensive anaesthesia.

Carotid bodies are highly specialized chemoreceptor organ situated at the bifurcation of common carotid artery. Carotid body tumor (CBT) is a rare non-chromaffin paraganglioma[1] arising from chemoreceptor cells found at carotid bifurcation.

It was first described by Von Haller in 1743. It usually presents as an asymptomatic neck swelling. Reported incidence 1-2/1,00,000 population.[2] The tumor is usually benign but may turn malignant by local invasion. Metastasis may even lead to death hence surgical excision has to be performed at the earliest.

Surgery is the definitive treatment for CBT. Surgical excision of the tumor poses several anesthetic challenges and a high incidence of perioperative morbidity and mortality (20–40%).[2,3] This case report is to highlight the anesthetic management and the problems encountered during CBT excision such as hemodynamic fluctuations and cardiac arrhythmias.

A 48-year-old female from southern part of Karnataka, who is homemaker by occupation, weighing 60 kg presented with a painless swelling in the left side of the neck just below the left angle of mandible for 3 years progressively increasing to reach the present size of 4 cm × 3 cm. She did not give any history of frequent episodes of fever, cough, and history of trauma or painful salivation. Patient doesn’t give any history of tachycardia, flushing, sweating, syncope, and hypertension.[4,5] No history suggestive of comorbid medical illness, pre-existent cerebrovascular accident (CVA). No history of similar complaints in the family.

On examination, lump was 4 cm × 3 cm in size, hard, non-tender, and non-pulsatile with no bruit heard over it. She denied complaints of dysphagia, hoarseness of voice, numbness or paralysis of tongue, and vision changes (cranial nerve complications).

General and physical examinations were unremarkable with heart rate 86 bpm and blood pressure (BP) 120/80 mmHg. Airway assessment was normal.

All routine hematological investigations were normal except for thyroid function test which revealed thyroid-stimulating hormone – 10 μIU/mL, T3 – 0.74 ng/mL, and T4 – 5.74 μg/dL. The patient was initiated on T. Thyronorm 25 mcg OD. IDL was normal. Electrocardiogram (ECG) and chest X-ray were within normal limits. 2D echocardiography was normal. Metanephrines-creatinine ratio 244.44 μg/gram of creatinine (increased in our case). Urinary metanephrines and vanillylmandelic acid were determined in those cases in which endocrine activity was suspected.[5]

USG neck revealed a well-defined heterogeneous mass lesion with internal anechoic tubular structures measuring 4.2 cm × 2.9 cm × 3.2 cm and the lesion is located at left carotid bifurcation and is seen to splay internal carotid artery (ICA) and external carotid artery (ECA). Color Doppler shows intense vascularity within mass lesion.

CT neck – A well-defined soft-tissue density lesion measuring 3.6 cm × 4.3 cm × 3 cm is seen at bifurcation of the left common carotid artery, splaying of ECA and ICA showing homogenous intense post-contrast enhancement. Diagnosis of CBT Shamblin type 2 was made.

Excision of the left-sided CBT was planned under general anesthesia (GA). The doubling time for the tumors is about 5 years, however, excision is the gold standard of treatment due to the risk of morbidity from compression symptoms and the possibility of malignant transformation.[6,7]

A written informed consent taken after explaining the risks associated with anesthesia and surgery during intraoperative and post-operative period to the patient’s attenders in their own language. Preoperatively, adequate blood and blood products and post-operative ventilator bed in surgical intensive care unit (ICU) were reserved.

Previous night of surgery patient was pre-medicated with Tab. Rantac 150 mg and Tab. Alprazolam 0.25 mg. Eight hours non-profit organization was advised. On the day of surgery, the patient was asked to continue Tab. Thyronorm 25 mcg OD.

On the day of surgery, pre-anesthesia checkup reviewed. Workstation checked emergency drugs and cross-matched blood and blood products kept ready. The patient was given nebulization with Lox 4% to reduce pressor response. The patient shifted to OR with 16G IV cannula and 1 pint RL infusion started. ASA standard monitors connected. The patient was pre-medicated with Inj. Glycopyrrolate 0.2 mg, Inj. Midaz 1 mg, and Inj. Fentanyl 100 mcg. Inj. Paracetamol 1 g + Inj. Magnesium sulfate 2 g + inj. Xylocard 60 mg + inj. Dexamethasone 8 mg was given over 15 min prior induction for reducing the intubation response. After adequate pre-oxygenation, the patient was induced with inj. Propofol 100 mg + inj. Scholine 75 mg under direct laryngoscopy flexometallic cuffed reinforced tube 7.5 mm passed into glottis opening and fixed at 20 cm after confirming bilateral equal air entry. Intraoperative monitoring done with ECG, SpO2, EtCO2, urine output, and ventilation variables maintained with inj. vecuronium and isoflurane.

The right femoral vein cannulation was done. Intraoperatively, hypotension was induced with nitroglycerine 0.5 mcg/kg/min and isoflurane 0.4–2% and mean arterial pressure (MAP) was maintained around 70–80 mmHg, heart rate around 70–80 bpm. IV fluids maintained with RL at a rate of 2 mL/kg/h.

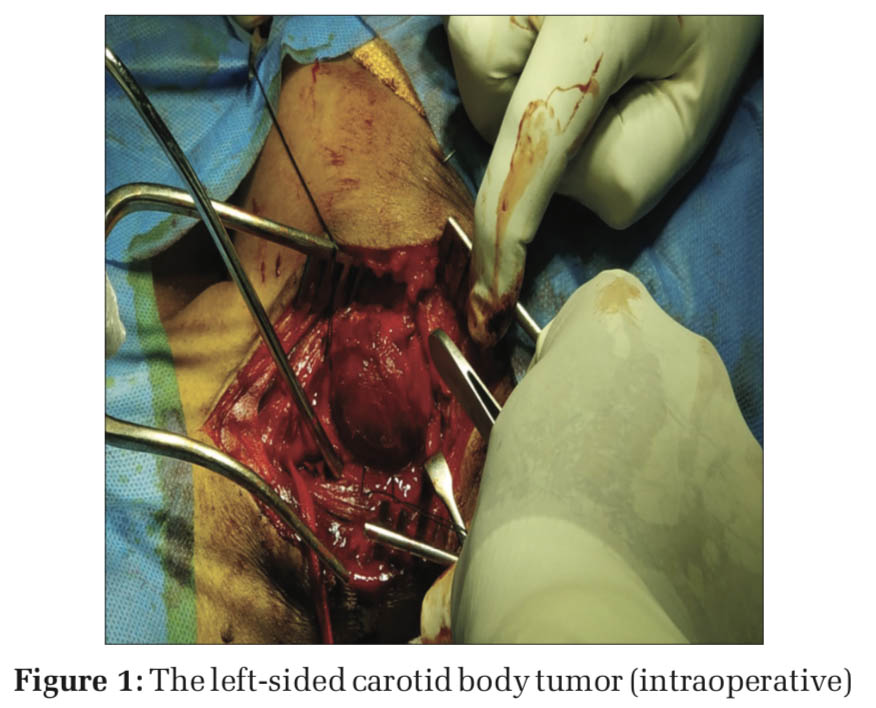

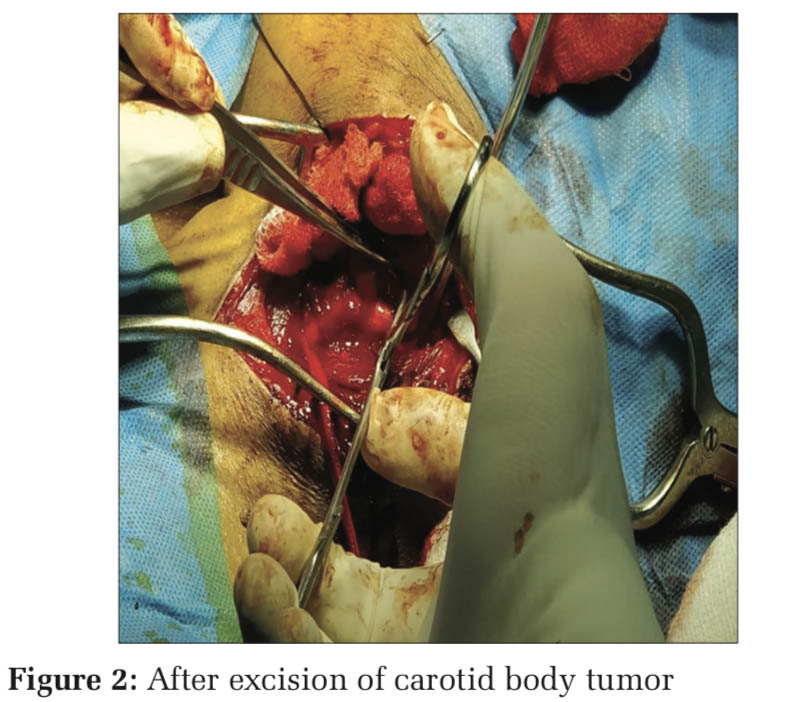

At the time of tumor handling (Figure 1), BP raised to 160/110 mmHg and tachycardia +, managed with inj. Dexmedetomidine 0.5 mcg/kg/h infusion (in view of analgesia and sedation). Immediately following tumor excision (Figure 2), BP fell to 70/50 mmHg, Dexmedetomidine and nitroglycerine infusion were stopped, the patient started on inj. Noradrenaline infusion 0.025 mcg/kg/min and 1 pint packed red blood cell (PRBC) and crystalloids were infused. At the end of surgery, patient’s vitals were stable with BP 130/80 mmHg and PR 100 beats/min. inj. Mannitol 20 g and inj. Citicoline 500 mg i.v. and inj. Heparin 5000 U i.v. given before clamping as a preventive measure to thromboembolic phenomenon and stroke.[2,8-10] Inj. Xylocard 60 mg i.v. given 90 min before extubation to reducethehemodynamicresponse.Inj.Neostigmine 2.5 mg + inj. Glycopyrrolate 0.5 mg given once patient met all extubation criteria and extubated after thorough suctioning of oral cavity and vocal cords are checked at extubation.

Post-extubation, the patient was conscious, oriented, moving all four limbs and cranial nerves were intact with no hoarseness of voice. The patient was clinically assessed for neurological deficits, since neurological monitoring was not available.

The patient shifted to post-operative ICU and monitored for neurological deterioration, hemodynamic instability, and arrhythmias.

Extra-adrenal paragangliomas are neoplasm arising from paraganglia located in the paravertebral sympathetic and parasympathetic chain.

Paragangliomas can arise anywhere in the tract and most common in abdomen, retroperitoneum, chest and mediastinum, head and neck location like jugulotympanic membrane, orbit, nasopharynx, vagal body, and carotid body.

In head and neck region of paragangliomas, most common location is carotid body. It arises from bifurcation of internal and external carotid arteries.

CBTs or paragangliomas are painless and slow growing tumors, often present as a long-standing growth which is asymptomatic and will be focused incidentally.

Benign CBTs often occurs at 40–70 years of age and more common in women. Metastasis can be seen in 2–9% of cases. About 0–4% are functional,[11] 10% are associated with cranial nerve palsy specially. Some may present with pulsatile sensation and tinnitus or tongue deviation or weakness depending on the location. Some may have symptom such as uncontrolled hypertension, tachycardia, facial flushing, and excessive sweating – suggests catecholamine secretory tumor. This warrants serum or urinary catecholamines and metabolites evaluation. Functional tumors are optimized by alpha- and beta-blockers. Patients with pre-existent cranial nerve deficits were not prescribed sedative premedication. Usually, CBT exploration and excision are done under general anesthesia/continuous cervical plexus block,[7] the latter is reserved for patients who are not fit for GA. Although slow-growing, painless, and usually benign, they can invade or exert pressure on neighboring neurovascular tissues and due to tendency for malignancy, surgical excision should be performed at the earliest. Radiotherapy is reserved for the elderly and those in poor general condition.

CBTs are vascular lesion, and this is reflected in imaging appearances. These lesions play apart the internal carotid and ECA, as they progress may even encase the carotid artery and nearby hemovascular structures, causing presenting symptoms. In our case also, similar picture was seen. Classically, lateral displacement and no vertical movements were seen.

A surgical classification was developed by Shamblin et al., based on the size of the tumor and difficulty of surgical resection. Our case was Shamblin II. More extensive surgery is required in II and III. Blood loss during resection had to be considered.

Anesthetic goals are hemodynamic stability and maintenance of cerebral perfusion pressure. Hence, we used hypotensive anesthesia using inj.

Nitroglycerine and inj. Dexmedetomidine with MAP maintaining between 70 and 80 mmHg. Four units of PRBCs were cross-matched and kept ready. A single dose of inj. Thiopentone was given while carotids were clamped for neuroprotection. Neuroprotection during carotid artery repairs normocapnia, Thiopentone (25–50 mg/kg bolus followed by 2–10 mg/kg/h infusion), and maintaining a good MAP with a relatively low systolic head during periods of blood loss and a high systolic pressure head during arterial clamping ensures optimal cerebral perfusion.

Electroencephalography and somatosensory evoked potentials can be used during surgery to monitor adequate cerebral perfusion. Carotid sinus stimulation causes reflex bradycardia, hypotension which usually responds to intravenous atropine. Alternatively, spraying with Inj. 2% Lignocaine at surgical site may be useful. External cardiac pacing if not responding to pharmacological treatment for reflex bradycardia and hypotension.

Catecholamine surge managed with short-acting antihypertensives such as esmolol, nitroglycerine, and nitroprusside. If cranial nerve palsy suspected prevent post-operative aspiration: Consider short- term nasogastric feeding or with percutaneous gastrostomy tube insertion. Vocal cord medialization should be employed in those with persisting vocal deficit.

Hypoventilation, non-obstructive central apnea kept in mind. Baroreflex failure syndrome, especially if bilateral, lead to hypertension: Clonidine and alpha- methyldopa used for treatment.

Take home message

Utmost vigilance by the anesthesiologist is essential during CBT excision. A detailed history, systemic examination, airway examination, cranial nerve examination, catecholamine secretion and other specific investigations, proper optimization of the patient, invasive monitoring, hypotensive anesthesia, and a high index of suspicion for possible complications (bleeding, CVA, and cranial nerve palsy), inotropes, and cross-matched blood and blood products in hand results in successful outcome.

The anaesthetist has a significant role in the management of CBT. They have to be involved in the preoperative planning, intraoperative and postoperative management (airway, intraoperative blood loss, stroke, cranial nerve dysfunction, and blood pressure control), are specific to the management of carotid body tumours. Increased awareness of these specific scenarios, appropriate management and timely intervention ensures minimal perioperative morbidity and mortality.

Subscribe now for latest articles and news.