We conclude our examination of Summa contra Gentiles with

- an overview of ScG, III.114–146 and the surrounding chapters;

- a consideration of why Aquinas talks about law, and what topics are omitted in our course;

- on the legal and religious nature of the human person;

- in light of providence, on the possibility of a philosophy of history;

- concluding thoughts on the Summa contra Gentiles and Christian wisdom.

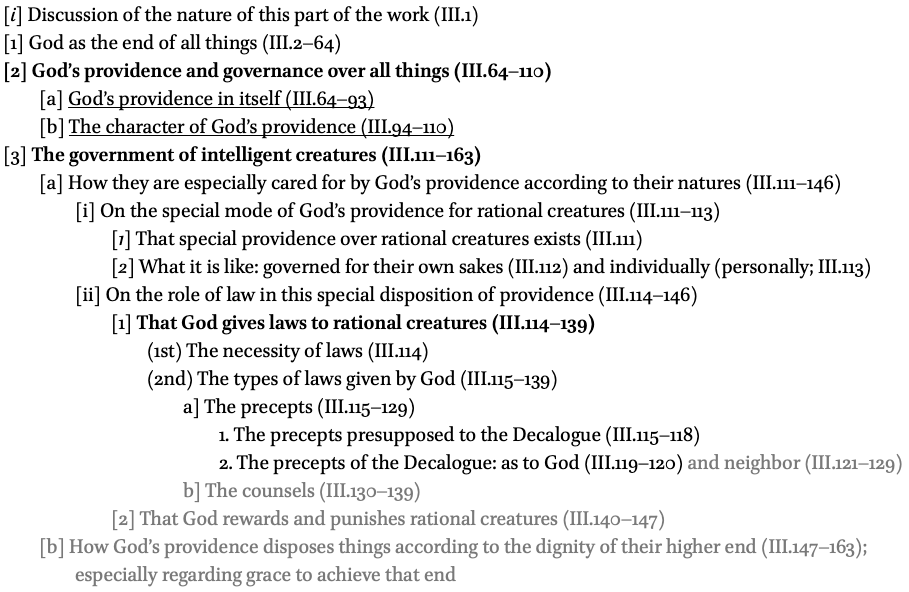

15.1. A Final Outline

The notions of creation, of human nature, of the ultimate good, of providence, and even of governance and human beings as under various other creatures, authority, and law, can all begin to seem structural and static.

Divine Providence, then, makes itself present in human history, in the history of thought and freedom, in the history of hearts and consciences. In man and with man the action of Providence acquires a “historical” dimension. It does this in the sense that it follows the rhythm and adapts itself to the laws of development of human nature, while remaining unchanged and unchangeable in the sovereign transcendence of its subsisting being. Providence is an eternal presence in the history of humanity—of individuals and communities.

John Paul II, General Audience of 21 May 1986; English translation at https://inters.org/John-Paul-II-Catechesis-Providence-Freedom (accessed 1 May 2023).

To understand ScG, Book III more fully, we must see how it includes the dynamic of history.

15.2. Providence, Law, and the Remaining Parts of ScG

Law is needed as part of providence because it directs specifically rational natures, because rational natures are capable, via knowledge, of participating in their own directedness to their ends. Law is given to free creatures, for “law should be given to those in whom is the power to act or not to act.” (ScG, III.114) Laws of nature for non-intelligent creation, then, are at best a very distant analogous use of term “law.”

These passages in ScG, III.118–117 are not the most systematic treatment by St. Thomas on the nature and species of law. Indeed, as Ferrariensis notes in his commentary, these chapters instead focus on the need for laws to be given to rational creatures and then the precepts related to the Decalogue (either those precepts presupposed to them or concerning those precepts themselves).

The presupposition of the Decalogue is the law of love of God and of neighbor. Adherence to God as to the supreme good could not but be the end of the law, since God is the ultimate common good of the created universe, and the law is the rational direction to the common good (see III.115, first argument). This adhesion to God is the love of God:

Lawgivers move those to whom the law is given by the command of the law which they promulgate. Now, in all things moved by a first mover, the more a thing participates in that movement, and the nearer it approaches to a likeness to that first mover, the more perfectly is it moved. Now God, the divine lawgiver, does all things on account of his love. Consequently, he who tends to him in that way, namely by loving him, tends to him in the most perfect manner. Now, every agent intends perfection in what he does. Therefore, the end of all legislation is that man love God.

ScG, III.116

This love would be, firstly, a natural love (see ScG, III.17–21). That is, to love God is commanded by the natural law. (See ST, Ia–IIae, q. 100, a. 3, obj. 1: “The first and principal precepts of the Law are, Thou shalt love the Lord thy God, and Thou shalt love thy neighbor … ” and and ad 1: “Those two principles are the first general principles of the natural law, and are self-evident to human reason, either through nature or through faith. Wherefore all the precepts of the decalogue are referred to these, as conclusions to general principles.”) That the efficacious or meritorious love of God requires grace is established later (see ScG, III.151). Because the law directs us to love God, it also directs us to love of neighbor (III.117): for God as the ultimate common good thereby unites those who love Him, and we love those whom God loves, and thus love of neighbor completes a type of community which seeks through its love a divine peace. This divine law elevates and perfects the love of the natural law:

The divine law is offered to man in aid of the natural law. Now it is natural to all men to love one another: a proof of this is that a man, by a kind of natural instinct, comes to the assistance of anyone even unknown that is in need—for instance, by warning him if he should have taken the wrong road, by helping him to rise if he should have fallen, and so forth—as though every man were intimate and friendly with his fellow-man. Therefore, mutual love is prescribed to man by the divine law.

ScG, III.117

In other words, providence provides laws for human beings, both natural and divine, as a pedagogical tool throughout history to direct us to our final end. This end cannot be reached without grace: “Grace establishes ‘friendship between God and man’ (III.157). Christian friendship has its source in the descent of the superior to the inferior, the strong to the weak.” (Hibbs, Dialectic and Narrative in Aquinas, 127) Indeed, grace perfects nature in ways that nature cannot fully anticipate:

According to Aristotle, exemplary friendships exist among privileged members of the city (polis), in whose lives social position, proper education, and virtue fortuitously coincide. With its offer of salvation to all, Christian universalism explodes the limited purview and dubious efficacy of pagan philosophy. One of Thomas’s criticisms of philosophy’s claim to teach with peremptory authority on the topic of beatitude is that it reaches only the few and even then with an admixture of error (III.39). Christian revelation reaches the low and the high alike and unites them to that good to which the philosophers aspire. Embracing not just the philosopher’s aspiration for the good, but also the longing of the whole “human genus,” revelation is more capacious than philosophy.

Ibid.

This is why Book III ends with a consideration of grace, including the greatest grace of all, that of becoming a saint (election, predestination to glory), and why Book IV is necessary to complete the account: “In the Christian context, imperfect happiness is not the last word on human happiness; it is ordered to a vision beyond time and history.” (Ibid., 131–32)

15.3. Man, the Religious Animal

St. Thomas argues in ScG, III.118 that faith is needed to attain this end, and, indeed, “divine law binds men to the true faith.” This kindly yet binding light comports with our rational nature, for sight is needed in order to fall in love:

For just as the beginning of material love is sight exercised through the material eye, so the beginning of spiritual love is the intellectual vision of a spiritual lovable object. Now, the vision of that spiritual lovable object, which is God, is impossible to us in the present life except by faith, because it surpasses natural reason, and especially inasmuch as our happiness consists in the enjoyment of it. Therefore, we need to be brought to the true faith by the divine law.

ScG, III.118

Indeed, we need sensible things to direct us to the worship of God (III.119). In this, our acts of religion, our piety and service and latria given to God are truly human: arising from our hylomorphic natures, body and soul. Indeed, a certain gnostic theology denies this, and thus “we must not wonder that heretics who deny that God is the author of our body decry the offering of this bodily worship to God. In which it is clear that they forget that they are men, inasmuch as they deem the presentation of sensible objects to be unnecessary for interior knowledge and affection.” This worship of God, latria, belongs to him alone (III.120); it ought not be given to other spiritual or superior beings, to some purported world soul or world-spirit, nor to physical idola.

The acts of this worship again befit the social nature of man:

As we said above, this external worship is necessary for man in order that his soul be roused to give spiritual homage to God. Now, custom is of great weight in moving the human mind to action, for we are more easily inclined to that which is customary. And the custom among men is that the honor given to the head of the state (for example, the king or the emperor) be given to no other. Therefore, the human mind should be urged to realize that there is one supreme cause of all by rendering to it something that it renders to no other. This is what we call the worship of latria.

Man, the rational animal, is by natural law directed to the truth; the truth is communicated to us by teachers in a community, especially the truth about God; but God is owed worship, or latria. So, we should say that man is a rational animal, and therefore a social-political animal, and additionally he is a religious animal. Here is Prof. Hibbs:

The reference [in III.120] to God as principle, author, and end recalls the division of the first three books and their dominant themes: the correction of idolatrous views about the divine nature, of views concerning creation that detract from the perfection of God and creatures, and of philosophical misconstruals of the sense in which God is the end of the rational nature. The correspondence between internal and external in divine worship presupposes the account of the union of soul and body. Human sacrifice orders the whole of creation to God. The convergence of these various themes underscores the importance of worship in the structure of the whole work.

Hibbs, Dialectic and Narrative in Aquinas, 123.

Why do we worship? How? In what manner and at whose behest? The particular answers to such questions cannot be deduced from general philosophical principles. In order to be assured of the rectitude of one’s worship in its specific detail, revelation is required. God must enter history, in some way or other, and reveal this to us.

15.4. The Theocentric Drama of History

It is sometimes said that the philosophical vision of the universe offered by St. Thomas Aquinas is static and has no room for history. It is true that his biology and cosmology did not include evolution or the innovation of entire new kinds of being through physical processes. However, it is not true that his philosophical principles and theological contemplation excluded history. How might we find the principles in St. Thomas’s thought “to ground in creation itself the historical reality of the universe, the theological origin of history?” Such is the concern of Marie Dominique Chenu, O.P. (in “Création et histoire,” in Étienne Gilson and Armand A. Maurer, eds., St. Thomas Aquinas, 1274-1974: Commemorative Studies, vol. 1 of 2, 391–399 (Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 1974), at 391; my translation.)

One way is to note what follows from the nature of the human person. The person is governed for his own sake in the cosmos, for “intellectual nature alone is free” (III.112) and the other, non-intellectual parts of the universe are not only for the sake of the overall perfection of the universe but for the sake of intellectual creatures. Providence has ordered the universe in such ways for those creatures as individual persons (III.113), and not just the maintenance of a species via the survival of physical individuals. For persons do not cease to exist once they exist. The history of persons is not just the biological repetition of a species, but a story:“Time is not only the succession of punctuated physical instants, a number immanent to movement; it is the interior measure of a destiny, included in some way in the eternal design of a transcendent providence actualized in personal and collective consciousness.” (ibid., 394)

Human beings have history because they are material beings:

A man does not come to be except in a body; his “incarnation” is at one and the same time the principle of individuality, or sociability, of history. An angel is neither social nor historical. It is sterile in its sufficiency. Because he is not a pure spirit, but a spirit which animates matter, man is not present to himself except by going out of himself. He does not see anything in his interior reality except by turning himself towards the world of objects and of other men.

Ibid.

Unlike the angel, the human being must go out into a world of physical exteriority and search for what is true and good; this requires material conditions, implies time, and implicates the other human beings who have brought him into existence. (Chenu’s ideas here are similar to ones elaborated in much more detail by Charles De Koninck; see the passages from his works noted in my essay, “Is Personal Dignity Possible Only If We Live in a Cosmos?” 236n29.)

Indeed: “Mobile being pursues its existence, but it cannot continue to exist in order to have had a history. Its end cannot consist in the pursuit of an existence always infinitely removed, that is unrealizable.” (De Koninck, The Cosmos, 263) Human history cannot be the mere timeline of a set of physical objects attaining to various stopping points. For, as we argued with St. Thomas in ScG, III.22–24, the heavens are directed intellectually towards the generation of the human form. An end-goal of human history looks for something definitive: “We also know that all this is provisory, that this agitation and the shape of the present world are only a shadow of that which in it is truly made for a definitive future where there will be no more history.” (De Koninck, “The Problem of Indeterminism,” 396) How could history end in its end? Can philosophy know the end-goal of all cosmic history?

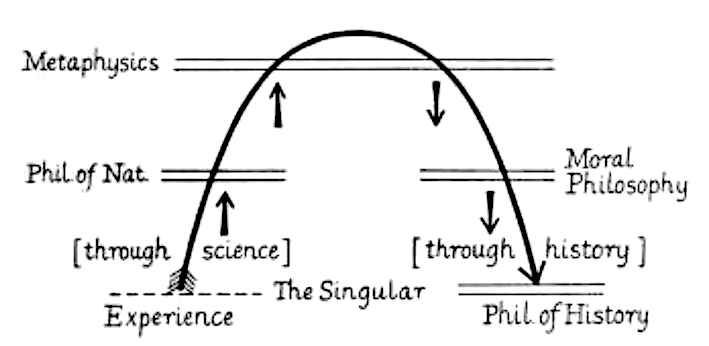

The general Thomistic answer is a qualified “no”. For instance, the philosopher Jacques Maritain provides this schematic regarding how a philosophy of history might come about.

The subject-matter of the philosophy of history is the unrolling of time, the very succession of time. Here we are confronted not only with the singularity of particular events, but with the singularity of the entire course of events. It is a story which is never repeated; it is unique. And the formal object of the philosophy of history is the intelligible meaning, as far as it can be perceived, of the unrolling, of the evolution in question.

Jacques Maritain, On the Philosophy of History (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1957), 35; 13–14 (for diagram).

Of course, as Maritain is well aware, since the singular is not knowable via philosophical demonstration, but only in a probable way, it proves impossible to deduce laws of history with certainty. General trends can be noted. But human freedom undermines deductive predictability. Instead, one might note the law of the passage from “sacral” to “secular” or “lay” civilizations, or one might consider the law of the political and social coming of age of the people. (See ibid., 111–15ff; Maritain gives various other examples but stresses they are not deterministic.) This philosophy of history is limited by its coordination with higher parts of philosophy and their relative inability to illuminate the inner meaning of the course of history, constituted in part by free human acts. Thus, while the philosophy of history borrows from metaphysics, it is principally moral philosophy:

Once more, the philosophy of history is no part of metaphysics, as Hegel believed. It pertains to moral philosophy, for it has to do with human actions considered in the evolution of mankind. And here we have either to accept or to reject the data of Judeo-Christian revelation. If we accept them, we shall have to distinguish between two orders—the order of nature and the order of grace; and between two existential realms, distinct not separate—the world, on the one hand, and the Kingdom of God, the Church, on the other. Hence, we shall have to distinguish between a theology of history and a philosophy of history. There is a theology of history, which is centered on the Kingdom of God and the history of salvation—a theology of the history of salvation—and which considers both the development of the world and the development of the Church, but from the point of view of the development of the Church. And there is a philosophy of history, which is centered on the world and the history of civilizations, and which considers both the development of the Church and the development of the world, but from the point of view of the development of the world. In other words, the theology of history is centered on the mystery of the Church, while considering its relation to the world; whereas the philosophy of history is centered on the mystery of the world, while considering its relation to the Church, to the Kingdom of God in a state of pilgrimage.

If this is true, it means that the philosophy of history pertains to moral philosophy adequately taken, that is to say to moral philosophy complemented by data which the philosopher borrows from theology, and which deal with the existential condition of that very human being whose actions and conduct are the object of moral philosophy.

Maritain, On the Philosophy of History, 37–38.

Is this adequate? Josef Pieper argues that “a philosophy of history that is severed from theology does not perceive its subject-matter.” (See The End of Time: A Meditation on the Philosophy of History, trans. by M. Bullock (London: Faber & Faber, 1954). Note that in the pages following those quoted above, Maritain expresses his own disagreement with Pieper.)

Pieper argues: this is because the beginning and end of human history is conceivable “only on acceptance of a pre-philosophically traditional interpretation of reality” such that “what really and in the deepest analysis happens in history is salvation and disaster” which are concepts due to some revelation (Pieper, The End of Time, 21, 22). To refuse these theological roots is to destroy it realiter as philosophy. This argument might go too far in its emphasis of philosophy’s dependence upon theology. However, what Pieper adds is that the meaning of history—since it is a kind of cosmic-scale motion providentially ordered by divine wisdom and freedom—can only be fully understood in light of its end-goal. It verges on the domain of prophecy. Is this goal the kingdom of God on earth? Is it the realization of the perfect freedom of the State (Hegel) or the oppressed masses (Marx)? The provision of a technological paradise of human free desire (liberal post-modernity)?

Pieper thinks the believer can see what the “rational” philosopher cannot, due to faith.

Thus for instance, the totalitarian work State, seen from the viewpoint of liberal thought, may appear something monstrously surprising in twentieth-century Europe, something unbelievable extreme—whereas the observer who regards history from the viewpoint of the Apocalypse ‘recognizes’ the totalitarian State, without surprise and with accurate understanding of its innermost historical tendencies and structures, as a milder preliminary form of the State of Antichrist.

Ibid., 51.

In another work devoted to this topic, Pieper suggests:

A modern statesman, Hermann Rauschning, instructed by some exceptionally intimate experiences with the totalitarian regime in Germany, thinks it quite possible that there could emerge a world civilization “of worldwide materialistic gratification based upon progressive dehumanization and absolutely subject to the total power of a World Grand Inquisitor.” The words “Grand Inquisitor” call to mind the name of another European who likewise anticipated the hidden potentialities of his time with seismographic sensitivity: Dostoevsky. In his Legend of the Grand Inquisitor we find the startling sentence: “In the end they will lay their freedom at our feet and say to us: Make us your slaves, but feed us.”

Josef Pieper, Hope and History, trans. by R. and C. Winston (New York: Herder and Herder, 1969), 84–85.

But even Pieper, arguing as he is against a conception of history conceived in terms of secular technological progress, emphasizes the little we can know, and that in general terms: “The Last Days will see an extreme concentration of the energy of evil and an unprecedented fury in the struggle against Christ and Christianity (and ‘against all good men’, Thomas Aquinas said).” (Ibid., 85) Rather, Pieper emphasizes that we are essentially viatores to something beyond death, and this opens up human historical existence to the structure of hope. Indeed:

Christ makes us loving exegetes; he teaches us how to read temporal, embodied signs in light of, as ordered to, eternity. In the time between the Incarnation and the judgment of the world, the sacraments constitute the principal signs of the divine; they continue the sanctification of the temporal, sensible order and anticipate the elevation of the cosmos in the “new heaven and new earth.”

Ibid., 87.

The Church through Her sacraments is this sensible link via liturgy in time of our end beyond time.

15.5. Defending Christian Wisdom in Season and Out of Season

If the deep interpretation of human history is theocentric, as outlined in the previous section, then there is never a time during which Christian wisdom can be forgotten or left undefended. Indeed, St. Thomas Aquinas’s own Summa that we have studied provides an example of how to bring to bear timeless philosophical and theological truths to address pressing questions of one’s day. However, our study has also shown that, with some name changes, many of the questions of Aquinas’s day in the 13th century, and certainly the most pressing, are still our own questions in the 21st century.

How then could philosophy presume to exclude in advance the possibility of being subsumed in some larger narrative that would satisfy its own teleology? It can do so only by placing greater emphasis upon rational certitude than upon the objects toward which the whole of the philosophical life tends. Christian wisdom opposes the totalitarian pretension of philosophy.

Hibbs, Dialectic and Narrative in Aquinas, 161.

That is, it opposes the abuse of philosophy; it opposes the elitist pretensions of some philosophers: “The exaltation of the lowly ‘idiots,’ as Thomas calls them in the original prologue, reflects an unexpected twist in the plot of creation.” (Ibid., 160) Yet even such fools need Christ the teacher:

Christ’s descent to the human order and his embrace of lowliness and suffering complicate the relationship between the two modes of truth. The second mode does not just supplement nature; rather, it manifests the higher in and through the lower; it corrects, transforms, and elevates nature.”

Ibid., 165.

The God-Man is the author come in search of His characters, characters who have been searching for their author. He is the treasure of Christian wisdom; He is the goal of human history:

After the last judgment has taken place, human nature will have reached its term. … Therefore, it is said: I saw a new heaven and a new earth (Rev 21:1); and: I create new heavens and a new earth; and the former things shall not be remembered or come into the heart. But be glad and rejoice forever (Isa 65:17–18). Amen.

ScG, IV.97

Thank you for the illuminating presentation on the philosophy of history. How does sociology fit into this account? The sort of thing exemplified by Tocqueville and Dawson? It seems to discover laws of societal development that are true for the most part.

Also, might the study of Providential action have some connection with the good of knowing a friend through his actions?

I would have to think about that more. And I should have included Dawson, who has a very “theocentric” view of history of course.

My initial though is that their studies of culture to discover the sort of “laws” that Maritain talks about (if I recall, Maritain even refers to Dawson in that book?).

By your last question do you mean that Christians can have some insight into the actions of Christ? That seems true—spiritual writers talk like that sometimes about the special providence in one’s life. On a handout for the actual course/lecture I included some selections from Caussaude and St. Francis de Sales on providence. That’s the importance of providence *not* being a universal providence (the way some Arabic Aristotelian thought), but down to the last particulars.

From St. Francis de Sales (quoted in Magnificat, January 2023):

«The Savior of our souls has not given us an ardent desire to serve him without also giving us the means to do so. The heart of our Redeemer measures and adjusts everything that happens in the world to the advantage of those who desire to serve his divine love without reserve. It will surely come, that hour for which you long, on the day that sovereign providence has named in the secret of his mercy, and then it will come with thousands of secret consolations. Your soul will be open to his divine goodness, which will change your stones into water, your snake into a staff, the thorns in your heart into roses whose perfume will refresh your spirit with their sweetness. For it is true that our faults, while they are in our souls, are so many thorns, but upon being brought forth by self-accusation, they are changed into fragrant blossoms. Our malice keeps them within our hearts, and the goodness of the Holy Spirit expels them.

«While taking a walk by yourself, or when you are alone at some other time, turn your eye to God’s universal will and see how he wills all the works of his mercy and justice, in heaven and on earth and under the earth. Then with profound humility, accept, praise, and then bless this sovereign will, which is entirely holy, just, and beautiful. Turn your eve next to God’s particular will, by which he loves his own and accomplishes in them different works of consolation and tribulation. Ponder this a while, as you consider not only the variety of his consolations, but above all the trials suffered by the good. Then, with great humility, accept, praise, and bless the whole of this will. Finally, consider this will in your own person, in all that befalls you for good or ill, and in all that can happen to you, except sin. Then, accept, praise, and bless all this and declare your intention always to honor, cherish, and adore this sovereign will, confiding to his mercy and giving him your own life and those of your loved ones. Conclude with an act of great confidence in his will, believing that he will do everything for us and for our happiness.»