By Ma

Having learnt some French, I was not flabbergasted by the singular/plural gender possessive nouns in German, although learners of the latter will take a bigger challenge of remembering the corresponding three grammatical genders (in terms of definite and indefinite articles) of every noun, namely male (der), female (die) and neutral (das), while French learners only need to distinguish the gender of nouns from male (le) and female (la).

The conjugation of German verbs is not surprising to me either, except that I had little fear (which I do even now!) whether I could recognize them efficiently and systematically. Anyway, I would like to share in this entry about the two interesting facts that bewildered me at first.

All German Nouns Must be Capitalized

Unlike English and French where the first letter of nouns except proper nouns is small, in German, all nouns must be capitalized. Such a rule has entirely subverted my way of reading passages written in European languages, for, in the case of English, I usually identify the beginning of the sentence with a capitalized word. Now, whenever I read German paragraphs, I need to look for the word after the full stop instead.

I have also discovered that the German rule of capitalization may also determine the meaning of the word. Take the pronouns sie and Sie as examples. Sie, when capitalized, represents the second person pronoun (you (formal)), while sie, written in small letters, denotes either a third-person “she” or the plural pronoun “they” in English.

Capitalization and punctuation, included in grammar rules, both play essential roles in conveying the meaning of a sentence. From a linguistics perspective, grammar carries meaning, and thus, capitalization of German nouns must signify something, too. I can’t really wait to unveil its hidden meaning!

You got various ways to form different German plural nouns

I have been amused by the multiple ways of forming various German plural nouns. In contrary to English, in most of cases of which you only have to add an “s” to the end of the noun to form a plural, a German plural noun can be done by putting “n/en”, “e”, “r/er” or “s” at the end of its singular equivalent. Sometimes an umlaut is even necessary. In some cases, a plural noun is spelled the same as its singular counterpart. An example would be Brötchen (English: bread), as both its singular and plural form share the same spelling.

German negation is more complicated than the English one, too. Instead of placing “not” before a noun in English, you need to consider the gender (and the case) of German nouns before deciding whether to use kein or keine. It thus seems to me that there is no shortcut to success, except memorizing every rule by heart.

Just as Plato, Aristotle and many others who subscribe to the belief that every existence bear a reason, I too, think that every grammatical rule exist for their own reason (In French, for instance, ne and pas are normally used together to emphasize the negative tone). Therefore, I believe that there must be a reason behind all German grammatical rules.

After all, German is a very interesting language that I want to know more (Hopefully I can take a German exam in the future)! Auf Wiedersehen!

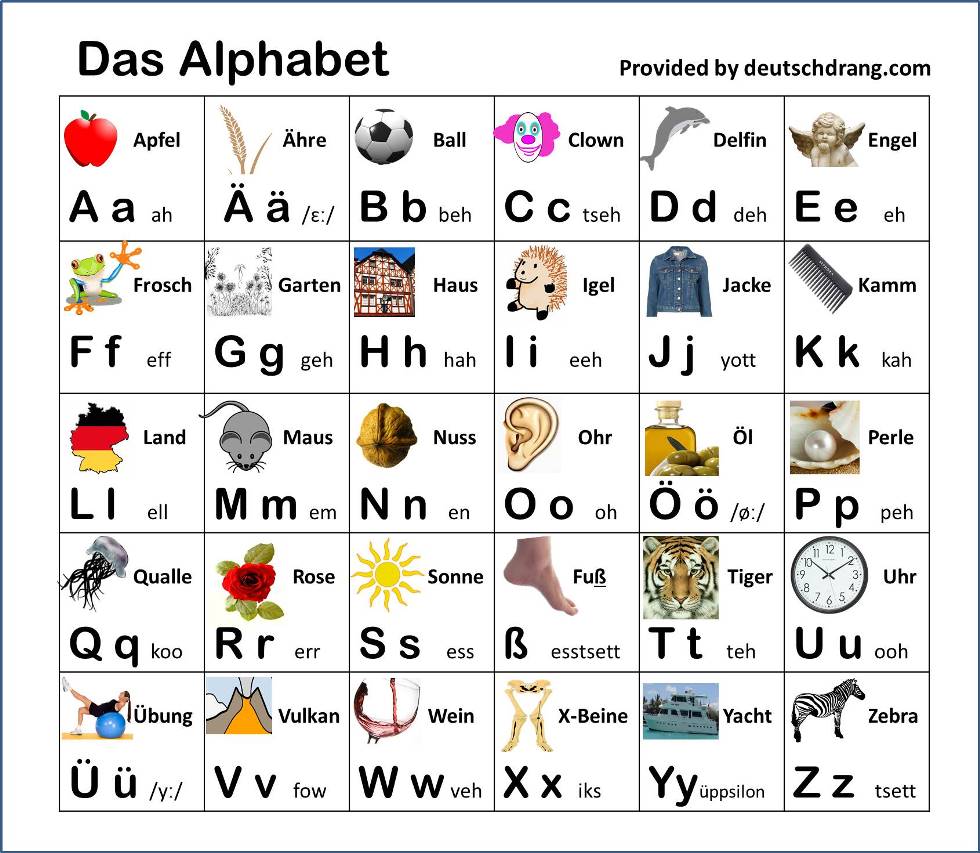

[Featured image: image40.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/German-Alphabet-With-Words.jpg]

i would wish to get pronounciations of the german alphabet

LikeLike