Despite arguably being Japan’s most famous and commercially successful filmmaker of his time, Akira Kurosawa found himself at the mercy of producers and investors who – by the time the 1970s came around – hesitated in funding any more of his projects. Kurosawa’s career seemed to be over by that point following a series of unsuccessful ventures into the world of television and the audience’s general indifference with regards to his work. As a result, a few days before Christmas, in 1971, the Japanese director decided to take his own life. The attempt resulted in severe wounds that managed to heal quickly and allowed Kurosawa to look ahead toward a new life.

Less than a year later, he was approached by the Soviet studio – Mosfilm. The Soviet executives offered him free artistic range in the selection and realization of his next film. The Soviet film industry was at an all time low and in need of a big hit. Kurosawa simply answered, “I want to tell the story of Dersu Uzala,” referring to the real life character of a Goldi hunter in Siberia at the turn of the 20th century portrayed in the autobiographical book of Russian explorer Vladimir Arsenyev. This great idea in scope (as it required on-location shooting in harsh weather conditions over a lengthy period of time with a large crew) and unlikely collaboration as well as first venture into directing a film in a foreign language proved to be the saving grace for Kurosawa, eventually winning the Oscar in 1976 for Best Foreign Language film and putting the director’s career back on track.

Seeing Dersu Uzala for the first time I was reminded of when I would sit in my grandfather’s lap and listen attentively to his stories. He’d recount his hunting expeditions to Mongolia and Iran in the 60s and 70s, carefully describing the landscape, the animals and the people that had contributed to his memorable adventures. The world he described so passionately was no more. Similarly, Dersu Uzala is about the inevitable disappearance of nature, man and the harmony that binds them, that same harmony and sense of purpose that my grandfather told me all about when I was six or seven.

In Kurosawa’s film, we are introduced to Captain Arsenev as he visits a logging site, looking for the place where his friend, Dersu, was buried some years ago. Unfortunately, nobody can tell anymore. It all looks the same – a cemetery of trees.

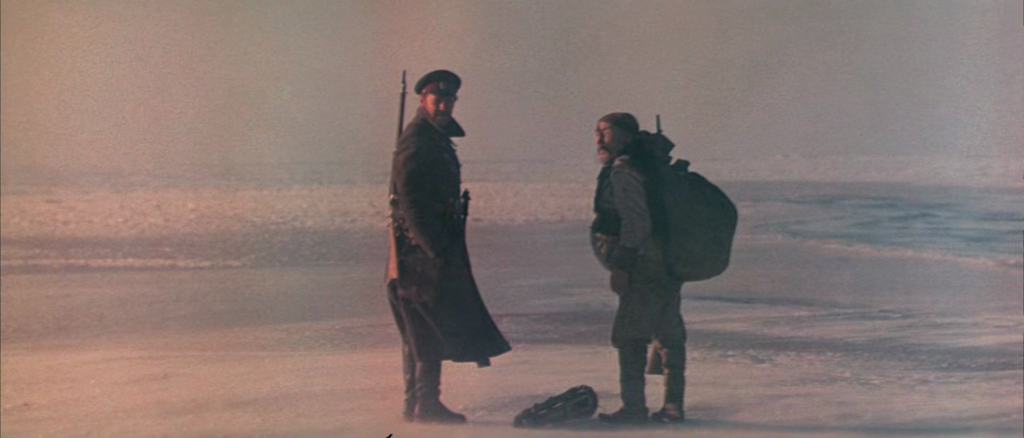

Arsenev takes us back to the time he first entered the Ussuri region as the leader of a topographic surveying expedition into the heart of the Siberian wilderness. As Arsenev and his men – novices to the dangers and harsh conditions of the immense area they must cover – venture into the wild they soon stumble upon an older man named Dersu Uzala. Dersu’s of small build, his backpack towering over him, armed with a rifle and an inseparable stick that helps him maintain his balance on uneven, slippery terrain. The two men immediately take a liking to each other and Dersu agrees to become their guide.

What follows is a beautiful and moving portrait of brotherhood.

Kurosawa’s trademark sense of action, movement and sound from the days of Seven Samurai, The Bad Sleep Well and Throne of Blood is replaced by calm, sweeping long-takes of men trudging in the wilderness, surrounded by nothing but nature and the beauty and threat that comes with it. With remarkable skill, Kurosawa is able to convey to us the epic scale of the landscape by effectively placing his characters in the center of every frame as if he were laughing at the disparity in proportions between man and his surroundings.

The captain senses that Dersu is no ordinary man. His speech in broken Russian points to a man from a different time and place, a man who, like Dersu himself says, “How old? Me not know. Me have lived plenty summers.” He used to have a family, a wife and kids, but life took them away from him. Now he must continue to make his own way, and the taiga is his shelter, his sanctuary. Arsenev is immediately drawn to the ways of the old man who talks to fire and exchanges thoughts with the sun and the moon because for Dersu the wilderness speaks its own language: “Fire is people. When fire angry, taiga burn for many days. Fire get angry, it frightening. Water get angry, it frightening. Wind get angry, it frightening. Fire, water, wind – three mighty people.“

For Arsenev – who is a product of modern society and loyal servant of the empire – Dersu is, like my grandfather was to me, a link to the past, a link to another way of life, of seeing and doing things, of carrying yourself in this world. Dersu reminds Arsenev that not everything needs to be measured and labelled. Some things he will not be able to define throughout his expedition, and that is fine. The immensity of the taiga will teach Arsenev to accept the unpredictability of things coming his way, with Dersu ready to accompany him and teach him how to carry an open dialogue with nature.

“Look around. All is people. Sun is the most important people. This people die, everyone die,” Dersu tells the captain. Dersu’s vision of the world is directly linked with the consequences of his actions, their impact on the world he inhabits. Arsenev, on the other hand, comes from a world where conquest is all that matters regardless of the cost. Kurosawa is fascinated by this difference in world view and makes of Arsenev a sympathetic character, willing to learn from the old man’s ways. It is through Dersu that the captain realizes how fragile his existence is in the wilderness. A winter coat and a rifle will not save you from a wind blowing at 70 mph and the chill of the night fast approaching.

The most beautiful and intense sequence of the film takes place on a frozen lake as the wind erases Arsenev and Dersu’s tracks, forcing them to confront the prospect of spending the night at freezing temperatures without adequate shelter. Dersu instructs the captain to start chopping and gathering as many reeds as he can in order to build a protection from the blizzard. The action is silent, the threat looming over the two characters as the camera tracks their desperate movements. It is through Kurosawa’s camera and staging that we see the miniscule scale of the human body, the frailty of it and how inconsequential our actions are in the face of the enormity of the wild.

Perhaps Dersu’s greatest teaching is the first one he provides Arsenev with: always keep in mind those that have come before you and those who will follow in your footsteps. For Dersu, there is no such thing as a stranger. A person is a fellow, just as a bear or wolf or snake is a fellow. Upon spending the night in a hut, Dersu asks the captain and his men to leave some food behind. What for? they ask him. “Put it in bark, leave it in hut.” Why? “Others come this way. Find dry wood there. Food to eat. People no die.” The older man sees life for what it is: a difficult journey that provides you with few answers. You have to respect others around you, whether it’s a person or an ant, or a bucket of cold water or a piece of hot coal. At the end of the day, you must always carry on the torch you were given the day you entered this world. When Dersu saves the captain’s life from certain death in freezing temperatures, he tells him, “Walk together, work together. No need to say thank you.“

I think that, like Captain Arsenev, Kurosawa found a grander meaning to life through Dersu’s story as the film portrays the kind of life that goes beyond career or reputation. It’s a life that factors in water, fire and the sky. In this life you must strive for survival and leave tracks for others who follow behind. You must consider the stars and the direction the wind blows. What is most devastating – and what probably Kurosawa considered the crux of the film – is that Arsenev was welcomed into Dersu’s world and was soon able to find his footing, yet when Dersu is forced by the end to try and make sense of modern society, he’s seen as an intruder, an alien who will never fit in. A species bound to go extinct. And that is our tragedy.