Abstract

The World Health Organization (WHO) 2017 classification of head and neck tumors has been just published and has reorganized tumors of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. In this classification, three new entities (seromucinous hamartoma, NUT carcinoma, and biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma) were included, while the total number of tumors has been reduced by excluding tumors if they did not occur exclusively or predominantly in this region. Among these entities, benign tumors were classified as sinonasal papillomas, respiratory epithelial lesions, salivary gland tumors, benign soft tissue tumors, or other tumors. In contrast, inflammatory diseases often show tumor-like appearances. The imaging features of these benign tumors and tumor-like inflammatory diseases often resemble malignant tumors, and some benign lesions should be given attention in the follow-up period and before surgery to avoid recurrence, malignant transformation, or massive bleeding. Understanding the CT and MR imaging features of various benign mass lesions is clinically important for appropriate therapy. The purpose of this article is to describe the clinical characteristics and imaging features of each of clinically important nasal and paranasal benign mass lesions, as classified according to the WHO 2017 classification of head and neck tumors, along with some inflammatory diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The 4th edition of the 2017 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of head and neck tumors has been published and tumors of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses were reorganized. This classification includes three new, relatively well-defined entities: seromucinous hamartoma, NUT carcinoma, and biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma, while the total number of entities has been reduced by excluding tumor types if they did not occur exclusively or predominantly at these sites or if they are discussed in detail in other sections [1]. However, a significant diversity of entities is still listed at the sinonasal region, and updating the knowledge of various disease entities and classifications is clinically crucial for radiologists.

Among tumors of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses, this article especially focused on the benign mass lesions including benign tumors and inflammatory diseases. This article also included nasopharyngeal lesions because the nasopharyngeal lesions often extend into the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses and sometimes occur in such regions. Although most benign lesions are curative by total resection or medical treatment, some benign lesions should be given attention in the follow-up period and before surgery. For example, sinonasal papillomas sometimes recur because of incomplete resection and have potential for malignant transformation, inflammatory diseases often present as tumor-like lesions and could be misdiagnosed as malignant tumors before surgical resection, and hypervascular tumors including hemangioma or nasopharyngeal angiofibroma may cause massive bleeding. Therefore, understanding the computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) imaging features of various types of nasal and paranasal benign mass lesions is clinically important for appropriate therapy.

The purpose of this review article is to describe the clinical characteristics and incidence of each of clinically important nasal and paranasal benign mass lesions classified according to the 2017 WHO classification of head and neck tumors (Tables 1 and 2), along with some inflammatory diseases. In addition, imaging features are reviewed and clinical and diagnostic tips of these benign mass lesions are described.

Sinonasal papillomas

Inverted type, oncocytic type, and exophytic type

Pathologic and clinical features

Sinonasal papillomas are benign epithelial neoplasms arising from Schneiderian mucosa and are histopathologically divided into three subtypes (inverted [62%], oncocytic [6%], and exophytic [32%]) [2].

Inverted papilloma (IP) is the most frequent papilloma of the sinonasal region, showing inverted growth with a multilayered epithelium [3]. Multiple inversions of the surface epithelium into the underlying stroma, which are composed of squamous and/or respiratory cells and lined by a distinct and intact continuous basement membrane, are a typical morphology. A non-keratinizing squamous or transitional epithelium frequently predominates and is covered by a layer of ciliated columnar cells. IPs are most frequent in the fifth and sixth decades of life and are 2.5–3 times more common in males than in females [3,4,5]. Patients present with non-specific symptoms such as nasal obstruction, polyps, epistaxis, rhinorrhea, hyposmia, and headache. The lateral wall of the nasal cavity and the median wall of the maxillary sinus are the most common locations. Although benign, IPs have a high propensity for recurrence, local aggressiveness, multicentricity, and malignant transformation (1.9–27% of IPs become squamous cell carcinoma [SCC]) [6, 7]. IPs are suspected to associate with human papillomatous virus (HPV) [3].

Oncocytic papilloma (OP) is derived from the sinonasal epithelium, which is composed of both exophytic fronds and endophytic invaginations lined by multiple layers of columnar cells with oncocytic features [8]. Intraepithelial microcysts containing mucin and neutrophils are characteristic of OPs. Most patients are older than the sixth decade of life with no sex predilection [5]. The main symptoms are nasal obstruction and intermittent epistaxis. OPs almost always occur unilaterally on the lateral nasal wall or in the paranasal sinuses. Malignant transformation is identified in about 10% of OPs. Unlike in inverted and exophytic papillomas, HPV has not been identified in OPs [8].

Exophytic papilloma (EP) is derived from the sinonasal mucosa composed of papillary fronds with delicate fibrovascular cores covered by a multilayered epithelium, which varies from squamous to ciliated pseudostratified columnar cells or may be transitional between the two [9]. EPs occur in the third to sixth decades of life and are 2–10 times more common in males than in females. Symptoms are unilateral nasal obstruction and epistaxis. EPs usually arise on the lower anterior nasal septum. Malignant transformation is extremely rare. As in IPs, EPs are also suspected to associate with HPV [9].

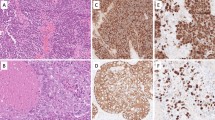

Imaging findings (Fig. 1)

Because imaging differences among the three subtypes of sinonasal papillomas have not been revealed [10, 11], we mainly describe the imaging features of IPs. CT could provide information about the site of origin of IPs, where focal hyperostosis on the sinus wall is often identified [12]. In contrast, bone sclerosis is usually more diffuse in other inflammatory sinonasal diseases. On MR imaging, IPs frequently show a lobulated shape with hyperintensity on T2-weighted image and iso- to hypointensity on T1-weighted image. A convoluted cerebriform pattern (CCP) is characteristic of IPs, showing alternating hypointense and hyperintense bands on T2-weighted image and contrast enhanced T1-weighted image, which resemble the cerebral gyri [13]. A focal loss of CCP, a necrotic lesion, or invasion to the surrounding tissue may be additional signs that indicate the presence of coexistent SCC (Fig. 2) [14].

Sinonasal inverted papilloma in a 38-year-old man. Sagittal CT shows a mass lesion in the left maxillary sinus and localized hyperostosis of the posterior wall of the maxillary sinus on the bone window (arrow) (a), which indicates the origin of the inverted papilloma. T2-weighted image shows a lobulated shape mass with a CCP (arrows) (b). T1-weighted image shows hypointensity (c) with heterogeneous contrast enhancement after contrast administration (arrows) (d)

Concomitant sinonasal inverted papilloma and squamous cell carcinoma in a 79-year-old woman. Axial (a) and coronal (b) T2-weighted images show a mass lesion in the left nasal cavity with a CCP (arrows). This mass shows hypointensity on T1-weighted image (c) and a CCP on contrast enhanced fat-suppressed T1-weighted image (d). Left ethmoid sinus and orbital invasion is identified, indicating that it is concomitant with squamous cell carcinoma (arrows). Diffusion is slightly restricted on axial DWI (b = 1000) (e) and the corresponding ADC map (f). Secondary maxillary sinus obstructive changes are easily differentiated from the primary lesion

Clinical and diagnostic tips

Because recurrences and malignant transformation are frequent in inadequate excision, identifying the hyperostotic region in adjacent bone is crucial before surgery. CCP is a characteristic sign of IPs, and a focal loss of CCP or a necrotic lesion may indicate the presence of coexistent SCC. A summary of the differentiation between IPs and other benign mass lesions is shown in Table 3.

Respiratory epithelial lesions

Respiratory epithelial adenomatoid hamartoma

Pathologic and clinical features

Respiratory epithelial adenomatoid hamartoma (REAH) is a benign neoplasm occurring in the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. The histopathologic feature is dominated by the presence of a submucosal glandular proliferation, which is lined by a ciliated respiratory epithelium with a polypoid appearance [15].

Median patient age is in the sixth decade of life, ranging from the third to ninth decades, and the male to female ratio is 7:1. The most common symptoms are nasal obstruction, rhinorrhea, and loss of smell [15,16,17,18]. Most REAHs are found on the anterior half of the olfactory clefts (OC) or the posterior nasal septum [15, 19]. Involvement of other sites occurs less common [15].

Imaging features (Fig. 3)

CT shows a homogeneous mass with clear enlargement of the OC without bone destruction [19]. MR imaging shows well-delineated tissue filling on T2-weighted image and homogeneous contrast enhancement. Although REAHs have been classically recognized as an isolated lesion, it also occurs coincident with diffuse sinonasal polyposis and other paranasal diseases. This coincident type of REAH also shows wide OC, as in the isolated type [19].

Respiratory epithelial adenomatoid hamartoma in an 80-year-old man. CT shows mass lesions in the bilateral olfactory clefts with clear widening of both sides of the olfactory clefts (arrows) (a, b). MR imaging shows well-delineated mass lesions with iso- to hyperintensity on T2-weighted image (c) and isointensity on T1-weighted image (d) with homogeneous contrast enhancement after contrast administration (e, f). Intracranial extension is not identified

Clinical and diagnostic tips

Significant widening of the OC with the characteristic location (in the anterior half of the OC) is a specific trait of REAHs. The main differential diagnosis is IPs, which require more extensive surgical excision to avoid recurrence or malignant transformation. In contrast, complete excision is curative in REAHs with no reports of malignant transformation [20].

Salivary gland tumors

Pleomorphic adenoma

Pathologic and clinical features

Pleomorphic adenoma (PA) has variable cytomorphological and architectural manifestations with epithelial/myoepithelial components and mesenchymal stromal components [21]. About 65% of PAs involve the major salivary glands, mainly the parotid, and 35% of PAs involve the accessory salivary glands. The nasal cavities and paranasal sinuses are only exceptionally involved. PAs in the nasal cavity display a more dominant epithelial component (versus stromal component) than is seen in PAs of the major salivary glands [21].

Most intranasal PAs are present in the third to sixth decades of life with a slight female predilection [22]. The most frequent symptom is unilateral nasal obstruction. About 80% of PAs arise in the nasal septal submucosa without destruction of surrounding tissue, and epistaxis and sinusitis can occur secondary to extension into the maxillary sinus. Malignant transformation has been reported in 2.4–10% of PAs [21].

Imaging findings (Fig. 4)

Multilobulated appearance is one of the key findings. CT can demonstrate adjacent bony changes such as displacement and expanding erosion [23]. Intratumoral calcifications sometimes occur. MR imaging shows iso- to hyperintensity on T2-weighted image, and hypointensity on T1-weighted image with heterogeneous curvilinear contrast enhancement, while non-enhancing parts representing cystic areas within the tumor can also be seen (9–40%) [24,25,26].

Clinical and diagnostic tips

Because complete excision is curative, it is important to identify the origin of intranasal PAs, which often originates from the nasal septum. A myxoid appearance in the post-operated region may be the most frequent feature of recurrence [24].

Benign soft tissue tumors

Leiomyoma (angioleiomyoma)

Pathologic and clinical features

Leiomyoma is a benign tumor with smooth muscle differentiation (and vascular differentiation in angioleiomyoma) [27]. Spindle cells are arranged in intersecting fascicles with oval to elongated and cigar-shaped nuclei, and an eosinophilic fibrillary cytoplasm. Leiomyomas are extremely rare (less than 1%) in the sinonasal tract. In most cases, tumors involve the nasal cavity, and more rarely involve the paranasal sinuses [28]. Angioleiomyoma, also called vascular leiomyoma, is a solitary and rare form of leiomyoma, accounting for 25–50% of all superficial leiomyomas. Angioleiomyomas show a prominent vasculature surrounded by smooth muscle cells with which the vessels are intimately associated [29, 30]. Calcification, ossification, fatty metaplasia, or myxohyaline degeneration may be seen and may suggest regression in longstanding lesions.

Adults are most commonly affected both in leiomyomas and angioleiomyomas, with no sex predilection in leiomyomas and a female predilection in angioleiomyomas (male to female = 1:2) [31]. Both tumors present as longstanding polypoid masses with nasal obstruction, epistaxis, and pain. The inferior nasal turbinate, nasal septum, and nasal vestibule are reported as the most common sites of occurrence [27].

Imaging findings

CT shows leiomyoma as an isodense mass that is primarily expansile rather than invasively destructive. On MR imaging, leiomyomas show slight hyperintensity relative to gray matter on T2-weighted image, and isointensity on T1-weighted image with moderate contrast enhancement. A cystic appearance is sometimes identified. In contrast, angioleiomyomas (Fig. 5) show heterogeneous hyperintensity on T2-weighted image and isointensity on T1-weighted image with remarkable contrast enhancement, which indicates its hypervascular nature [32].

Angioleiomyoma in a 78-year-old man. CT shows a homogeneous hypodense expansile mass lesion in the lateral wall of the nasal cavity (arrow) (a). On MR imaging, the lesion shows isointensity on T2-weighted (b) and T1-weighted image (c) with remarkable contrast enhancement after contrast administration (arrow) (d)

Clinical and diagnostic tips

An elliptical, well-defined, homogeneous and expansile mass without bony erosion may help to suggest a diagnosis of sinonasal leiomyomas. Because of its hypervascular nature, fine-needle aspiration or biopsy should be avoided in angioleiomyomas [27]. A summary of the differentiation among benign mass lesions with marked contrast enhancement is shown in Table 4.

Hemangioma

Pathologic and clinical features

Hemangioma is a benign neoplasm of vascular phenotype, divided primarily into capillary and cavernous types, depending on the dominant microscopic vessel size [27]. Capillary hemangioma is by far more common than cavernous hemangioma in the sinonasal region, while cavernous hemangioma tends to be larger than capillary hemangioma [33, 34].

Capillary hemangiomas, which include lobulated capillary hemangioma or pyogenic granuloma, are composed of capillary sized vessels lined with flattened epithelial cells separated by a collagen stroma. Although capillary hemangiomas occur in all ages (median: in the fifth decade of life), there are peaks in children and adolescent males, females in their reproductive years, then an equal sex distribution beyond the fifth decade of life [27].

Cavernous hemangiomas are composed of multiple, large, cystic, thin-walled, and blood-filled spaces lined by endothelial cells, and separated by scant connective tissue stroma. Cavernous hemangiomas tend to arise in men mainly with the fifth decade of life [35].

Both diseases show similar symptoms, including epistaxis and nasal obstruction. Capillary hemangioma usually arises from the nasal septum, whereas cavernous hemangiomas are more likely to occur on the lateral wall of the nasal cavity.

Imaging findings

CT shows capillary hemangioma (Fig. 6) as a well-circumscribed mass with an intensely enhancing tumor surrounded by a hypoattenuated peripheral rim [36]. Bone remodeling and erosion are identified as the tumors become larger than 2 cm. MR imaging shows heterogeneous hyperintensity with a hypointense peripheral rim on T2-weighted image, and hypointensity on T1-weighted image with marked contrast enhancement and a non-enhanced thin peripheral ring. Signal voids within the mass are often identified. Dynamic contrast enhanced study may show a washout pattern (in about 75% of capillary hemangiomas) [37].

Capillary hemangioma in a 74-year-old man. CT shows a homogeneous isodense mass lesion (a) on the left nasal septum with remarkable contrast enhancement (arrow) (b). MR imaging (c–f) which is performed 1 month after CT shows a heterogeneous hyperintense lesion on T2-weighted image (c), which has become enlarged. T1-weighted image (d) shows hypointensity with remarkable medial contrast enhancement after contrast administration (arrows) surrounded by non-enhancing hematoma (arrowheads) (e, f)

CT shows cavernous hemangioma (Fig. 7) as a large and inhomogeneous mass with heterogeneous enhancement of either a centripetal or multifocal nodular pattern. MR imaging shows hyperintensity on T2-weighted image, and homogeneous isointensity on T1-weighted image with mild to moderate contrast enhancement, which is called “progressive enhancement” [34, 38].

Cavernous hemangioma in a 70-year-old man. CT shows a homogeneous isodense mass lesion in the left maxillary sinus with heterogeneous contrast enhancement after contrast administration (arrow) (a–c). T2-weighted image shows heterogeneous hyperintensity (d). T1-weighted image shows hypointensity (e) with homogeneous contrast enhancement after contrast administration (f). Axial dynamic contrast enhanced fat-suppressed T1-weighted images show a gradual enhancement pattern (arrows) (g–i)

Clinical and diagnostic tips

On MR imaging, hyperintensity on T2-weighted images, and marked enhancement with a washout pattern and a non-enhanced thin peripheral ring are characteristic of capillary hemangiomas, while mild hyperintensity on T2-weighted image and a progressive enhancement pattern are characteristic of cavernous hemangiomas. Preoperative embolization can decrease bleeding in both types.

Schwannoma

Pathologic and clinical features

Schwannoma is a slow growing, encapsulated, and spindle cell tumor composed of hypercellular Antoni A areas and hypocellular/myxoid Antoni B areas [27].

Adults are mainly affected (mean age: in the sixth decade) with no sex predilection. Common symptoms are headache, nasal obstruction, facial pain, and Horner syndrome. Sinonasal schwannomas arise from the branches of the cranial nerves (V and IX–XII) and autonomic nervous system, occurring especially in the ethmoid sinus, followed by the maxillary sinus and nasal cavity. Tumors may expand into the orbit, nasopharynx, and cranial cavity. Complete surgical excision is curative, and malignant transformation or postoperative recurrence is rare [27].

Imaging findings (Fig. 8)

CT shows an inhomogeneous hypodense soft tissue mass, with smooth erosion and scalloping of the adjacent bony walls [39, 40]. Tumors may expand into the orbit, nasopharynx, and cranial cavity. MR imaging shows iso- to hyperintensity on T2-weighted image, and hypointensity on T1-weighted image. Target sign may be seen with a biphasic pathologic pattern of the central Antoni A area (hypointensity) and peripheral Antoni B area (hyperintensity). Sinonasal schwannomas may show more T2-hypointensity than schwannomas in other body parts because of a high ratio of the hypercellular Antoni A area [34]. Although schwannomas are hypovascular tumors, most cases show marked and delayed contrast enhancement on dynamic study, which may be due to poor venous drainage and pooling of contrast materials, whereas some cases show poor contrast enhancement. Cystic and hemorrhagic changes are common [40].

Schwannoma in an 11-year-old boy. CT shows a homogeneous isodense expansile mass lesion in the right nasal cavity (arrow) (a). T2-weighted image shows heterogeneous iso- to hyperintensity (b). T1-weighted image (c) shows isointensity with remarkable contrast enhancement and a central unenhanced cystic area after contrast administration (arrow) (d). Restricted diffusion is seen on axial DWI (b = 1000) (e) and the corresponding ADC map (f)

Clinical and diagnostic tips

The imaging feature of sinonasal schwannoma is non-specific, but a tubular tumor shape and target sign may be characteristic features and may be helpful for preoperative diagnosis and surgical planning [40].

Other tumors

Meningioma

Pathologic and clinical features

Sinonasal meningioma, often blended with the surface squamous or respiratory epithelium, is arranged in lobules of whorled syncytial meningothelial cells [41, 42]. Of the 15 histological types of meningioma, the meningothelial, transitional, metaplastic, and psammomatous types are common in sinonasal meningiomas. Most of these meningiomas are grade 1 tumors, whereas grade 2 and 3 meningiomas are rare [41]. Sinonasal meningiomas account for fewer than 2% of all meningiomas, including both primary and secondary types, which are based on the absence or presence of intracranial attachments, respectively [43]. Primary extracranial meningiomas of the sinonasal tract with no direct cranial attachment are extremely rare, whereas secondary sinonasal meningiomas, which show direct extension, are much more common [41].

Adults (mean age: in the fifth decade) are mainly affected with a female predilection (male to female = 1:1.7–2.1). Symptoms are generally non-specific, including a mass or polyp and nasal obstruction. Sinonasal meningiomas most commonly involve the nasal cavity, followed by the frontal sinus [41].

Imaging findings (Fig. 9)

CT shows a mass with adjacent bone erosion or hyperostosis. In most cases, direct extension by permeative growth from the intracranial primary lesion can be documented. MR imaging shows various signal intensities on T2-weighted image, and hypointensity on T1-weighted image with homogenous contrast enhancement [44].

Invasive meningioma (chordoid meningioma, grade 2 [atypical grade for this region]) in a 23-year-old man. Coronal CT shows a huge homogeneous hyperdense mass lesion extending from the intracranial cavity to the ethmoid sinus and nasal cavity (a). Axial (b) and sagittal T2-weighted images (c) show homogeneous hyperintensity and an intratumoral flow void (arrows). Coronal contrast enhanced fat-suppressed T1-weighted image shows remarkable homogeneous enhancement (d). Diffusion is slightly restricted on axial DWI (b = 1000) (e) and the corresponding ADC map (f)

Clinical and diagnostic tips

Identification of hyperostosis may be useful for diagnosis of meningiomas. In the diagnosis of secondary extracranial meningioma, a characteristic feature that displays a different signal intensity and enhancement patterns between intra and extracranial components may be identified [45].

Benign lesions

Ectopic pituitary adenoma

Pathologic and clinical features

Ectopic pituitary adenoma (EPA) is a benign anterior pituitary gland neoplasm that does not involve the sella turcica [46, 47].

Patient age at presentation varies widely (between the first to ninth decades of life; older than patients with typical pituitary adenoma) with a slight female predilection (male to female = 1:1.3) [48]. Symptoms include nasal obstruction, sinusitis, rhinorrhea, discharge, and headache. Some patients present with endocrinopathic manifestations (about 70% of the EPAs are functional, including Cushing’s syndrome, acromegaly, and hyperparathyroidism). EPAs most frequently occur along the path of migration of Rathke’s pouch, especially in the sphenoid sinus. Concomitantly, a normal pituitary gland is often identified in the normal location, and to date only 15 cases of sphenoid sinus EPAs associated with empty sella have been reported in the literature [49, 50]. However, Yang et al. [51] reported that 62.5% of EPA patients showed empty sella, suggesting that EPAs may occur in association with empty sella, which probably gives a diagnostic clue to this entity. Although the association between EPA and empty sella is not clearly understood, one possible explanation is that an empty sella develops secondary to abnormal migration of Rathke’s pouch, with only a few pituitary progenitor cells reaching the sella, resulting in the formation of empty sella [50].

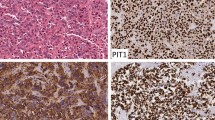

Imaging findings (Fig. 10)

Imaging studies are required to exclude direct extension from the sella turcica. CT shows a well-defined soft tissue mass with homogeneous isodensity or slight hyperdensity [52]. Bone destruction is common, while calcification is rare. MR imaging shows iso- to hyperintensity on T2-weighted image and hypo- to isointensity on T1-weighted image. Some EPAs could include sacciform hemorrhage, or necrosis. A specific bubble-like or thin hyperintensity, and cribriform appearance on contrast enhanced T1-weighted image may be identified [49]. Empty sella may also be identified in EPAs [51].

Ectopic pituitary adenoma in a 73-year-old man with hyperthyroidism. Axial T2-weighted image shows a heterogeneous isointense mass lesion in the sphenoid sinus (arrow) (a). Sagittal T1-weighted image shows isointensity (b). Sagittal contrast enhanced T1-weighted image shows mild contrast enhancement (arrow) (c). The normal pituitary gland can be also identified in the sella turcica (arrowhead)

Clinical and diagnostic tips

Although rare, EPAs should always be considered in differential diagnosis of sphenoid sinus mass lesions in older adults regardless of coexistence with empty sella. Even if the pituitary gland is radiologically normal, the pharyngeal-cranial migration route must be reviewed in patients presenting with clinical and laboratory findings of a functioning pituitary adenoma, to exclude the possibility of EPAs.

Benign soft tissue tumors

Nasopharyngeal angiofibroma

Pathologic and clinical features

Nasopharyngeal angiofibroma (NA), which is also called juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma, is a rare, benign, highly vascular, and locally aggressive neoplasm, composed of two components: vascular and stromal tissues. The blood vessels are of various sizes, shapes, and thicknesses, ranging from slit-like capillaries to irregularly dilated and branching vessels. The stroma consists of bipolar or stellate fibroblastic cells, which appear to be arranged around the blood vessels [53].

NAs develop almost exclusively in adolescent and young males (mean age; 17 years), showing a puberty-associated growth because of their frequent expression of an androgen receptor. Patients present with the classic triad of nasal obstruction, epistaxis, and nasopharyngeal mass. Most NAs arise from the pterygopalatine fossa and nasopharynx of the posterolateral nasal cavity wall [53].

Imaging findings (Fig. 11)

CT shows a remarkably enhanced mass that is centered within the sphenopalatine foramen [54]. Anterior bowing of the posterior wall of the maxillary antrum and widening of the pterygopalatine fossa are typical. As the tumor grows, extension to surrounding tissue and destruction of adjacent bone are sometimes identified. MR imaging is superior to CT for detecting the intracranial extension, which is seen in 10–30% of cases. MR imaging shows iso- to hyperintensity on T2-weighted image, and hypointensity on T1-weighted image with avid contrast enhancement. A flow void may be seen because of the hypervascularity [54].

Nasopharyngeal angiofibroma in a 33-year-old man. CT shows a homogeneous isodense mass lesion in the pterygopalatine fossa (a) expanding the posterior wall of the maxillary sinus on the bone window (arrow) (b). On MR imaging, the lesion shows hyperintensity on T2-weighted image (c) and isointensity on T1-weighted image (d) with remarkable contrast enhancement after contrast administration (arrow) (e), which indicates hypervascularity

Clinical and diagnostic tips

Patient’s age and sex, specific location with a bowing posterior wall of the maxillary antrum, and hypervascularity can be characteristic features, which allow diagnosis and accurate estimation of the extent without recourse to the dangers of biopsy. Because of the hypervascularity, angiography is also diagnostic and useful for identifying the feeding artery (usually the internal maxillary artery) and preoperative embolization [53].

Inflammatory diseases

Inflammatory polyp

Pathologic and clinical features

Sinonasal inflammatory polyp often originates from the maxillary sinus. Inflammatory polyp is caused by allergy, vasomotor rhinitis, infections, cystic fibrosis, aspirin intolerance, or nickel exposure. Fluid accumulation in the lamina propria results in polyp formation. Furthermore, inflammatory polyp may be associated with mucocele or antral cyst formation in the maxillary sinus because of increased pressure in the antrum, resulting in expansion through an accessory or secondary ostium below the middle meatus. Antrochoanal polyp is a relatively rare type of inflammatory polyp, which often arises from the ostium of the maxillary sinus, extends through the ostium, across the choana, and into the nasopharynx, and usually occurs unilaterally [35].

Patient age at presentation varies widely with no sex predilection. Symptoms are non-specific, most commonly including nasal obstruction and rhinorrhea.

Imaging findings (Fig. 12)

CT shows inflammatory polyp, including antrochoanal polyp, as an oval hypodense mass but may be hyperdense because of increased protein content or fungal infection. MR imaging shows inflammatory polyp, including antrochoanal polyp, as hypo- to hyperintensity on T2-weighted image associated with the components, and isointensity on T1-weighted image with peripheral contrast enhancement. In particular, an antrochoanal polyp tends to be a single, unilateral expansile process, revealing nearly total maxillary sinus opacification, mucosal thickening, and extension into the nasopharynx [35].

Antrochoanal polyp in a 74-year-old woman. CT shows a homogeneous isodense mass lesion in the left nasal cavity (a). T2-weighted image shows a hyperintense mass lesion with partial hypointensity (arrows) (b). Coronal (c) and sagittal (d) contrast enhanced fat-suppressed T1-weighted images show peripheral enhancement of the nasal lesion, which extends into the nasopharynx (arrows). No restricted diffusion is seen on axial DWI (b = 1000) (e) and the corresponding ADC map (f)

Clinical and diagnostic tips

Although a large inflammatory polyp, especially antrochoanal polyp, may be misdiagnosed as other tumors, such as IPs, because of overlapping imaging features, peripheral enhancement may be useful for differentiation [55]. Sinonasal inflammatory polyps, including antrochoanal polyps, can coexist with a wide variety of pathologic entities ranging from infective granuloma diseases to malignant tumors [56].

Fungus ball

Pathologic and clinical features

Fungal disease of the paranasal sinuses is mainly categorized into two primary categories: invasive (acute and chronic) and noninvasive (allergic and fungus ball) [57,58,59]. Among these fungal diseases, fungus ball is a noninvasive dense conglomeration of fungal hyphae usually in a single sinus cavity. The disease tends to occur in older immunocompetent individuals. Patients are usually asymptomatic, although they may present with mild pressure sensation involving one of the paranasal sinuses, nasal discharge, and cacosmia [58]. The maxillary sinuses are most commonly affected, followed by the sphenoid, frontal, and ethmoid sinuses [59].

Imaging findings (Fig. 13)

CT shows fungus ball as a high-density mass with calcification. Surrounding circumferential hypoattenuating mucosal thickening is usually present, indicating chronic sinusitis. The bony margins of the involved sinus are usually intact. MR imaging shows severe hypointensity, like air, on T2-weighted image, and iso- to hypointensity on T1-weighted image [58]. Contrast enhanced T1-weighted image demonstrates thickening and enhancement of the surrounding inflamed mucosa [59].

Fungus ball in a 76-year-old man. CT shows an isodense lesion with partial calcification (arrow) (a). T2-weighted image shows severe hypointensity (arrow) (b). T1-weighted image (c) shows hypointensity with mucosal contrast enhancement after contrast administration, whereas fungus ball itself does not show contrast enhancement (d). The fungus ball shows hypointensity (arrows) on axial DWI (b = 1000) (e) and the corresponding ADC map (f) due to the presence of calcifications and paramagnetic metals

Clinical and diagnostic tips

A hyperattenuating mass within an opacified single sinus in a non-atopic immunocompetent patient is consistent with fungus ball [58].

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

Pathologic and clinical features

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), which was formerly called Wegener granulomatosis, is an idiopathic necrotizing granulomatous vasculitis. GPAs involve lungs (95%), paranasal sinuses (90%), kidneys (85%), nose/nasopharynx (65%), and joints (65%) [60]. GPAs characteristically present with nasal involvement accompanied by pulmonary and renal disease. Histologic features are vasculitis, necrosis, and granulomatous inflammation [60].

The disease presents at any age, but is more common in the fourth and fifth decades of life with no sex predilection [60].

Imaging findings (Fig. 14)

The imaging features of sinonasal involvement of GPAs include bilateral sinus opacification, mucosal thickening, osseous erosion and destruction, and neo-osteogenesis. Osseous erosion has a predilection for the anterior ethmoid region. CT can reveal the erosive changes characterized by punctate osseous destruction, especially in the nasal septum, and neo-osteogenetic sclerotic appearance [61]. MR imaging shows hypointensity on T2-weighted and T1-weighted images with inhomogeneous contrast enhancement [62].

Clinical and diagnostic tips

The imaging features of GPA-induced sinonasal disease overlap with those of several diseases, such as nasal cocaine necrosis and NK/T cell lymphoma. A clinical history of cocaine usage is diagnostic of nasal cocaine necrosis. Hard palate defects are common with nasal cocaine necrosis and lymphoma. Osseous erosion underlying mucosal inflammation can be seen in lymphoma. In contrast, these findings are not characteristic of GPAs. Erosions affecting the nasal septum and turbinates are more specific for GPAs [60].

IgG4-related disease

Pathologic and clinical features

IgG4-related disease (IgG4-RD) is a rare systemic condition that has been found to be responsible for fibro-inflammatory lesions of numerous organs such as the pancreas, liver, biliary tract, salivary glands, lymph nodes, orbits, kidneys, and lungs [63]. It is currently reported that IgG4-RDs have a particular tropism for the trigeminal nerve, particularly its infraorbital branch [64]. These lesions often show homogeneously enhanced sinonasal soft tissue masses on CT and MR imaging and may be misdiagnosed as other sinonasal tumors [65].

In the head and neck region, mean patient age is in the sixth decade of life with no sex predilection [63].

Imaging findings (Fig. 15)

Involvement of the trigeminal branches, maxillary sinus, and nasal septum is reported as sinonasal lesions of IgG4-RDs [64, 66]. Among them, most characteristical imaging finding of IgG4-RDs is an infraorbital lesion, which often shows as a soft tissue mass. CT shows enlargement of the infraorbital canal. On MR imaging, the infraorbital branch shows a homogeneously enhancing soft tissue mass involving the skull base along the second and third divisions of the trigeminal nerves. These lesions show hypointensity relative to the brain on T2-weighted image [64, 67].

Clinical and diagnostic tips

Differential diagnoses include aggressive malignant tumors with perineural invasion and malignant lymphoma [68]. Diagnosis may be challenging in cases of lymphoma, with a clinical presentation close to the orbital inflammation. However, lymphoma presents with a strongly restricted apparent diffusion coefficient, which may be helpful for differentiation [64].

Chronic expanding hematoma

Pathologic and clinical features

Chronic expanding hematoma (CEH) is a non-neoplastic hemorrhagic lesion, which consists of a variable state of hematoma surrounded by an organized fibrous capsule [69]. CEH is also called organized/organizing hematoma or blood boil. Mechanisms for the formation of CEHs are the following: (1) repeated hemorrhage in the semiclosed lumen (especially in the maxillary sinus) forms a hematoma encapsulated by fibrosis; (2) the encapsulation prevents the absorption of the hematoma and induces vascularization, which causes rebleeding and increasing pressure within the hematoma; and (3) the progressive expansion of the hematoma causes the demineralization of adjacent structures [69].

Patients present between the second to eighth decades of life with no sex predilection. Symptoms are epistaxis, nasal obstruction, facial swelling, and rhinorrhea. CEHs usually occur in the maxillary sinus unilaterally. Because of their expanding features, CEHs are often misdiagnosed as malignant tumors. Complete removal of the hematoma with the fibrous capsule is not only the standard treatment but also diagnostically important to differentiate it from malignant tumors with massive hematoma. Furthermore, partial removal causes massive bleeding, resulting in prompt recurrence [70].

Imaging findings (Fig. 16)

CT shows a heterogeneous hypo- to hyperdense mass with expansion of the maxillary sinus wall, while bone destruction is rare [70]. The lesions have patchy heterogeneous contrast enhancement. The central hematoma shows variable signal intensity because of the time of lesion on both T2-weighted and T1-weighted image, while the fibrous capsule is characterized by a hypointense rim on T2-weighted image, and iso- to hypointensity on T1-weighted image. Heterogeneous enhancement in the central portion is common because of the variable stage of the hematoma. Rim enhancement may be seen if neovascularization occurs within the fibrous capsule [33].

Chronic expanding hematoma in a 70-year-old man. CT shows a hyperdense mass lesion (a) in the right maxillary sinus with expanding the sinus wall (arrows) (b). T2-weighted image shows heterogeneous hypo- to hyperintensity (arrows) (c). Dynamic contrast enhanced fat-suppressed T1-weighted images (d–f) show a gradual heterogeneous enhancement pattern (arrows)

Clinical and diagnostic tips

Although preoperative embolization of CEH is still controversial and is not always performed, preoperative embolization may decrease the intraoperative bleeding volume if the feeding artery is found with angiography because CEH sometimes causes massive bleeding [71, 72].

Conclusions

In this article, we demonstrated the imaging features of nasal and paranasal benign mass lesions according to the latest 2017 WHO Classification. An overview of specific imaging findings of nasal and paranasal benign mass lesions described in this manuscript is provided in Table 5. Because some of these benign lesions show aggressive imaging findings like malignant tumors, familiarity with the CT and MR imaging features of various nasal and paranasal benign mass lesions will facilitate accurate diagnosis and clinical decision-making.

References

Thompson LDR, Franchi A. New tumor entities in the 4th edition of the World Health Organization classification of head and neck tumors: nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses and skull base. Virchows Arch. 2017;472(3):315–30.

Barnes L. Schneiderian papillomas and nonsalivary glandular neoplasms of the head and neck. Mod Pathol. 2002;15:279–97.

Hunt JL, Bell D, Sarioglu S. Sinonasal papillomas, inverted type. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ, editors. WHO classification of head and neck tumours. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC Press; 2017. p. 28–9.

Kim DY, Hong SL, Lee CH, Jin HR, Kang JM, Lee BJ, et al. Inverted papilloma of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses: a Korean multicenter study. Laryngoscope. 2012;122:487–94.

Vorasubin N, Vira D, Suh JD, Bhuta S, Wang MB. Schneiderian papillomas: comparative review of exophytic, oncocytic, and inverted types. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2013;27:287–92.

Nudell J, Chiosea S, Thompson LD. Carcinoma ex-Schneiderian papilloma (malignant transformation): a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic study of 20 cases combined with a comprehensive review of the literature. Head Neck Pathol. 2014;8:269–86.

Eggesbo HB. Imaging of sinonasal tumours. Cancer Imaging. 2012;12:136–52.

Hunt JL, Chiosea S, Sarioglu S. Sinonasal papillomas, oncocytic type. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ, editors. WHO classification of head and neck tumours. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC Press; 2017. p. 29–30.

Hunt JL, Lewis JS, Richadson M, Sarioglu S, Syrjänen S. Sinonasal papillomas, exophytic type. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ, editors. WHO classification of head and neck tumours. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC Press; 2017. p. 30–1.

Terada T. Malignant transformation of exophytic Schneiderian papilloma of the nasal cavity. Pathol Int. 2012;62:199–203.

Karligkiotis A, Bignami M, Terranova P, Gallo S, Meloni F, Padoan G, et al. Oncocytic Schneiderian papillomas: clinical behavior and outcomes of the endoscopic endonasal approach in 33 cases. Head Neck. 2014;36:624–30.

Lee DK, Chung SK, Dhong HJ, Kim HY, Kim HJ, Bok KH. Focal hyperostosis on CT of sinonasal inverted papilloma as a predictor of tumor origin. Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28:618–21.

Ojiri H, Ujita M, Tada S, Fukuda K. Potentially distinctive features of sinonasal inverted papilloma on MR imaging. Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175:465–8.

Jeon TY, Kim HJ, Chung SK, Dhong HJ, Kim HY, Yim YJ, et al. Sinonasal inverted papilloma: value of convoluted cerebriform pattern on MR imaging. Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29:1556–60.

Wenig BM, Franchi A, Ro JY. Respiratory epithelial adenomatoid hamartoma. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ, editors. WHO classification of head and neck tumours. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC Press; 2017. p. 31–2.

Lee JT, Garg R, Brunworth J, Keschner DB, Thompson LD. Sinonasal respiratory epithelial adenomatoid hamartomas: series of 51 cases and literature review. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2013;27:322–8.

Wenig BM, Heffner DK. Respiratory epithelial adenomatoid hamartomas of the sinonasal tract and nasopharynx: a clinicopathologic study of 31 cases. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1995;104:639–45.

Aviles Jurado FX, Guilemany Toste JM, Alobid I, Alos L, Mullol IMJ. The importance of the differential diagnosis in rhinology: respiratory epithelial adenomatoid hamartoma of the sinonasal tract. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 2012;63:55–61.

Hawley KA, Ahmed M, Sindwani R. CT findings of sinonasal respiratory epithelial adenomatoid hamartoma: a closer look at the olfactory clefts. Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34:1086–90.

Fitzhugh VA, Mirani N. Respiratory epithelial adenomatoid hamartoma: a review. Head Neck Pathol. 2008;2:203–8.

Bell D, Bullerdiek J, Gnepp DR, Hunt JL. Salivary gland tumours. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ, editors. WHO classification of head and neck tumours. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC Press; 2017. p. 33.

Sciandra D, Dispenza F, Porcasi R, Kulamarva G, Saraniti C. Pleomorphic adenoma of the lateral nasal wall: case report. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2008;28:150–3.

Ozturk E, Saglam O, Sonmez G, Cuce F, Haholu A. CT and MRI of an unusual intranasal mass: pleomorphic adenoma. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2008;14:186–8.

Motoori K, Takano H, Nakano K, Yamamoto S, Ueda T, Ikeda M. Pleomorphic adenoma of the nasal septum: MR features. Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21:1948–50.

Baron S, Koka V, El Chater P, Cucherousset J, Paoli C. Pleomorphic adenoma of the nasal septum. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2014;131:139–41.

Takita H, Takeshita T, Shimono T, Tanaka H, Iguchi H, Hashimoto S, et al. Cystic lesions of the parotid gland: radiologic-pathologic correlation according to the latest World Health Organization 2017 classification of head and neck tumours. Jpn J Radiol. 2017;35:629–47.

Thompson LDR, Bullerdiek J, Flucke U, Franchi A. Benign soft tissue tumour. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ, editors. WHO classification of head and neck tumours. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC Press; 2017. p. 47–50.

Veeresh M, Sudhakara M, Girish G, Naik C. Leiomyoma: a rare tumor in the head and neck and oral cavity: report of 3 cases with review. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2013;17:281–7.

He J, Zhao LN, Jiang ZN, Zhang SZ. Angioleiomyoma of the nasal cavity: a rare cause of epistaxis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;141:663–4.

Agaimy A, Michal M, Thompson LD, Michal M. Angioleiomyoma of the sinonasal tract: analysis of 16 cases and review of the literature. Head Neck Pathol. 2015;9:463–73.

Huang HY, Antonescu CR. Sinonasal smooth muscle cell tumors: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 12 cases with emphasis on the low-grade end of the spectrum. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:297–304.

Yang BT, Wang ZC, Xian JF, Hao DP, Chen QH. Leiomyoma of the sinonasal cavity: CT and MRI findings. Clin Radiol. 2009;64:1203–9.

Kim JH, Park SW, Kim SC, Lim MK, Jang TY, Kim YJ, et al. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging findings of nasal cavity hemangiomas according to histological type. Korean J Radiol. 2015;16:566–74.

Yang B, Wang Y, Wang S, Dong J. Magnetic resonance imaging features of schwannoma of the sinonasal tract. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2015;39:860–5.

Thompson LDR, Fanburg-Smith JC. Update on select benign mesenchymal and meningothelial sinonasal tract lesions. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:95–108.

Lee DG, Lee SK, Chang HW, Kim JY, Lee HJ, Lee SM, et al. CT features of lobular capillary hemangioma of the nasal cavity. Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31:749–54.

Yang BT, Li SP, Wang YZ, Dong JY, Wang ZC. Routine and dynamic MR imaging study of lobular capillary hemangioma of the nasal cavity with comparison to inverting papilloma. Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34:2202–7.

Vargas MC, Castillo M. Sinonasal cavernous haemangioma: a case report. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2012;41:340–1.

Yu E, Mikulis D, Nag S. CT and MR imaging findings in sinonasal schwannoma. Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27:929–30.

Kim YS, Kim HJ, Kim CH, Kim J. CT and MR imaging findings of sinonasal schwannoma: a review of 12 cases. Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34:628–33.

Ro JY, Bel LD, Nicolai P, Thompson LDR. Meningioma. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ, editors. WHO classification of head and neck tumours. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC Press; 2017. p. 50–1.

Rushing EJ, Bouffard JP, McCall S, Olsen C, Mena H, Sandberg GD, et al. Primary extracranial meningiomas: an analysis of 146 cases. Head Neck Pathol. 2009;3:116–30.

Thompson LD, Gyure KA. Extracranial sinonasal tract meningiomas: a clinicopathologic study of 30 cases with a review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:640–50.

Baek BJ, Shin JM, Lee CK, Lee JH, Lee KH. Atypical primary meningioma in the nasal septum with malignant transformation and distant metastasis. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:275.

Shimono T, Akai F, Yamamoto A, Kanagaki M, Fushimi Y, Maeda M, et al. Different signal intensities between intra- and extracranial components in jugular foramen meningioma: an enigma. Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26:1122–7.

Katabi N, Hunt JL, Thompson LDR, Wenig BM. Benign and borderline lesions. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ, editors. WHO classification of head and neck tumours. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC Press; 2017. p. 72–3.

Bobeff EJ, Wisniewski K, Papierz W, Stefanczyk L, Jaskolski DJ. Three cases of ectopic sphenoid sinus pituitary adenoma. Folia Neuropathol. 2017;55:60–6.

Thompson LD, Seethala RR, Muller S. Ectopic sphenoid sinus pituitary adenoma (ESSPA) with normal anterior pituitary gland: a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic study of 32 cases with a comprehensive review of the english literature. Head Neck Pathol. 2012;6:75–100.

Wu X, Wen M. CT finding of ectopic pituitary adenoma: case report and review of literature. Head Neck. 2015;37:E120–4.

Liang J, Libien J, Kunam V, Shao C, Rao C. Ectopic pituitary adenoma associated with an empty sella presenting with hearing loss: case report with literature review. Clin Neuropathol. 2014;33:197–202.

Yang BT, Chong VF, Wang ZC, Xian JF, Chen QH. Sphenoid sinus ectopic pituitary adenomas: CT and MRI findings. Br J Radiol. 2010;83:218–24.

Erdogan N, Sarsilmaz A, Boyraz EI, Ozturkcan S. Ectopic pituitary adenoma presenting as a nasopharyngeal mass: CT and MRI findings. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2012;114:414–6.

Prasad ML, Franchi A, Thompson LDR. Soft tissue tumours. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ, editors. WHO classification of head and neck tumours. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC Press; 2017. p. 74–5.

Mishra S, Praveena NM, Panigrahi RG, Gupta YM. Imaging in the diagnosis of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2013;3:1.

Chawla A, Shenoy J, Chokkappan K, Chung R. Imaging features of sinonasal inverted papilloma: a pictorial review. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2016;45:347–53.

Kale SU, Mohite U, Rowlands D, Drake-Lee AB. Clinical and histopathological correlation of nasal polyps: are there any surprises? Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2001;26:321–3.

Morpeth JF, Rupp NT, Dolen WK, Bent JP, Kuhn FA. Fungal sinusitis: an update. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1996;76:128–39; quiz 39–40.

Mossa-Basha M, Ilica AT, Maluf F, Karakoc O, Izbudak I, Aygun N. The many faces of fungal disease of the paranasal sinuses: CT and MRI findings. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2013;19:195–200.

Raz E, Win W, Hagiwara M, Lui YW, Cohen B, Fatterpekar GM. Fungal Sinusitis. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2015;25:569–76.

Pakalniskis MG, Berg AD, Policeni BA, Gentry LR, Sato Y, Moritani T, et al. The many faces of granulomatosis with polyangiitis: a review of the head and neck imaging manifestations. Am J Roentgenol. 2015;205:W619–29.

Lohrmann C, Uhl M, Warnatz K, Kotter E, Ghanem N, Langer M. Sinonasal computed tomography in patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2006;30:122–5.

Muhle C, Reinhold-Keller E, Richter C, Duncker G, Beigel A, Brinkmann G, et al. MRI of the nasal cavity, the paranasal sinuses and orbits in Wegener’s granulomatosis. Eur Radiol. 1997;7:566–70.

Andrew N, Kearney D, Selva D. IgG4-related orbital disease: a meta-analysis and review. Acta Ophthalmol. 2013;91:694–700.

Soussan JB, Deschamps R, Sadik JC, Savatovsky J, Deschamps L, Puttermann M, et al. Infraorbital nerve involvement on magnetic resonance imaging in European patients with IgG4-related ophthalmic disease: a specific sign. Eur Radiol. 2017;27:1335–43.

Katsura M, Morita A, Horiuchi H, Ohtomo K, Machida T. IgG4-related inflammatory pseudotumor of the trigeminal nerve: another component of IgG4-related sclerosing disease? Am J Neuroradiol. 2011;32:E150–2.

Ishida M, Hotta M, Kushima R, Shibayama M, Shimizu T, Okabe H. Multiple IgG4-related sclerosing lesions in the maxillary sinus, parotid gland and nasal septum. Pathol Int. 2009;59:670–5.

Toyoda K, Oba H, Kutomi K, Furui S, Oohara A, Mori H, et al. MR imaging of IgG4-related disease in the head and neck and brain. Am J Neuroradiol. 2012;33:2136–9.

Sasaki T, Takahashi K, Mineta M, Fujita T, Aburano T. Immunoglobulin G4-related sclerosing disease mimicking invasive tumor in the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. Am J Neuroradiol. 2012;33:E19–20.

Nishiguchi T, Nakamura A, Mochizuki K, Tokuhara Y, Yamane H, Inoue Y. Expansile organized maxillary sinus hematoma: MR and CT findings and review of literature. Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28:1375–7.

Lee HK, Smoker WR, Lee BJ, Kim SJ, Cho KJ. Organized hematoma of the maxillary sinus: CT findings. Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:W370–3.

Omura G, Watanabe K, Fujishiro Y, Ebihara Y, Nakao K, Asakage T. Organized hematoma in the paranasal sinus and nasal cavity–imaging diagnosis and pathological findings. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2010;37:173–7.

Kuo CL, Li WY, Luo CB, Ho CY. Ruptured internal carotid artery aneurysm presenting as a sinonasal organized hematoma: conventional approach may endanger life. J Neuroimaging. 2014;24:199–201.

Funding

We received no financial support for this review article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

Ethical statement

This manuscript is a review article and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

About this article

Cite this article

Tatekawa, H., Shimono, T., Ohsawa, M. et al. Imaging features of benign mass lesions in the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses according to the 2017 WHO classification. Jpn J Radiol 36, 361–381 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11604-018-0739-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11604-018-0739-y