Abstract

Cardiac tumors are rare and benign masses account for the most part of the diagnosis. When malignant cancer is detected, primary or secondary cardiac lymphoma are quite frequent. Cardiac lymphoma may present as an intra or peri-cardiac mass or, rarely, it may diffusely infiltrate the myocardium. Although often asymptomatic, patients can have non-specific symptoms. Acute presentations with cardiogenic shock, unstable angina, or acute myocardial infarction are also described. Modern imaging techniques can help the clinicians not only in the diagnostic phase but also during administration of chemotherapy. A multidisciplinary counseling and serial multi-parametric assessment (echocardiography, cardiac troponin) seem to be the most effective approach to prevent possible fatal complications (i.e., cardiac rupture). Currently, only chemo- and radiotherapy are available options for treatment, but the prognosis remains poor. This is a case of secondary cardiac lymphoma presenting as a mediastinal mass with large infiltration of the heart and the great vessels with a good improvement after only one cycle of chemotherapy. It demonstrates the importance of an early diagnosis to modify the natural history of the disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Malignant neoplasm, such as sarcomas and primary lymphomas, is very rare. In fact, almost three out of four cardiac masses are benign tumors.1 However, metastatic invasion of the heart is quite frequent.2

Cardiac involvement in case of lymphoma is commonly clinically silent and often discovered post-mortem.2 Nonetheless, some patients may complain symptomatic manifestations.2,3

Although the modern combination schemes of chemotherapy, the general prognosis of primary or secondary cardiac lymphomas is usually poor, partly because of diagnostic delay.3,4 So, it is crucial to suspect and detect early cardiac involvement, especially with the support of imaging techniques. Echocardiography is the method of choice to detect cardiac involvement and complications.5

In this case report, we present an unusual case of massive cardiac infiltration due to mediastinal lymphoma, where the multidisciplinary approach in the diagnostic phase and during the first cycle of chemotherapy has been of primary relevance. The close imaging follow-up and the efficacy of hematologic therapies have been crucial to avoid potential life-threatening complications.

Case Report

On May 2020, a 54-year-old man came to our attention in order to undergo surgical ablation of persistent atrial fibrillation. He was symptomatic for palpitation, dyspnea, and mild chest oppression.

During the previous year, the patient had multiple episodes of atrial fibrillation and he was also hospitalized for pericardial effusion causing cardiac tamponade and for intraparenchymal cerebral hemorrhage which necessitated surgical evacuation. In that occasion, the pericardiocentesis revealed hematic fluid with bacterial growth, so he was treated with antibiotic therapy.

Before undergoing surgical ablation, the trans-thoracic echocardiogram pointed out a marked and diffused thickening of the myocardium and a large iso-echogenic peri-cardiac mass as well as sign of pulmonary and systemic congestion, mild pericardial effusion, and severe left pleural effusion (Figure 1).

Trans-thoracic echocardiography - parasternal long-axis view. On the left, it is evident the marked and diffused thickening of the myocardium, especially of the interventricular septum, the posterior, the interatrial septum and the right ventricular free wall, which appear hypokinetic. Also, the large iso-echogenic mass takes up space around the ascending aorta and in the anterior mediastinum (yellow narrow). On the right, the view after the first chemotherapy regimen

The chest X-ray and the computed tomography confirmed the presence of an abundant solid tissue in the anterior mediastinum, surrounding the great vessels. Multiple enlarged lymph nodes above and below the diaphragm were also described (Figure 2).

Chest X-ray - The upper picture shows the parenchymal thickening of the left inferior pulmonary lobe with associated pleural effusion. Note the enlarged mediastinum and the increased dimension of the heart. The inferior picture shows the chest X-ray after the first cycle of chemotherapy, with net reduction of the pleural effusion and the mediastinal mass

To complete the evaluation, positron emission tomography (PET) was performed and confirmed subdiaphragmatic lymph nodes and global accumulation of 18-FDG in the heart (Figure 3).

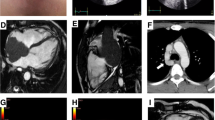

Also, the cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) demonstrated massive invasion of the heart by the mediastinal mass, whose cleavage borders were not evaluable. Marked thickening of the myocardium with sign of diffuse edema on T2-mapping and the presence of late gadolinium enhancement were found (Figure 4)

Cardiac magnetic resonance. A 3-chamber view and mid-ventricular short-axis view before chemotherapeutic treatment. Note the massive invasion of the heart by the mediastinal mass, whose cleavage borders are not evaluable; the myocardium appears thickened. Diffuse edema in T2-weighted sequences was detected, with a similar diffuse LGE pattern. B After the first regimen of chemotherapy, no more myocardial edema and late gadolinium enhancement were noticed, with near-normalization of left ventricle thickness

The bone marrow biopsy did not find any localization of the malignancy, thus the thoracoscopic biopsy of the mediastinum was performed. The histological examination confirmed the diagnosis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (Figure 5). Thus, according to hematological indications, a chemotherapy regimen was started. Given the massive cardiac infiltration, according to the hematologist consultation, the first dose of the R-CHOP cycle (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) was administered in three stages. During the administration, echocardiogram was performed every 48 hours for the first 10 days, in order to detect early occurrence of complications, such as pericardial effusion or cardiac rupture.

The patient improved quickly. On day 7 after the first cycle of chemotherapy, dyspnea and chest oppression disappeared, as well as the signs of systemic congestion, together with concomitant significant reduction of the mediastinal mass and complete resolution of the pleural effusion.

Lastly, there was a spontaneous restoration of sinus rhythm and a heart rate reduction (Figure 6).

Despite the rapid improvement of the cardiac infiltration, after 5 months of chemotherapy, the patient had a progression of the disease with cerebral localization, so he was addressed to palliative cares.

Discussion

This case reflects many features of the secondary cardiac lymphoma.

Primary cardiac lymphoma (PCL) is a non-Hodgkin lymphoma which involves primarily the heart and/or the pericardium, with the bulk of the tumor intrapericardial.6 Unlike PCL, secondary cardiac localization accounts for 25% of all disseminated lymphoma.3

The most prevalent secondary lymphomas are B-cell origin non-Hodgkin lymphomas, and diffuse large B-cell is the most frequent (80%). It usually affects immunocompetent male patients, with a median age of 60 years old.7 In case of immunocompromised individuals, cardiac lymphoma is usually virus-related (Epstein–Barr virus, human herpes virus-8) .3

On the other hand, cardiac involvement from Hodgkin lymphoma has been rarely detected.2

Typically, both primary and secondary cardiac lymphomas can be infiltrative, intramural, or may appear as epicardial lesions, singular or multiple, with a particular tropism for the pericardium and the right side of the heart.3 Usually cardiac valves are spared.5

Sometimes, cardiac involvement in disseminated lymphoma is widespread, affecting not only the pericardium but also the myocardium, diffusely.8 Some case reports showed uncommon presentations like massive cardiac infiltration mimicking restrictive cardiomyopathy.6,8,9,10

The localization of the tumor reflects the way of its spread. It can be lymphatic, hematogenous or by direct extension.8 A triple-way diffusion is possible, especially in case of widespread lymphoma.

Although it is usually detected during autopsy, non-Hodgkin lymphoma may be clinically evident and lead to potentially lethal complication.

Signs and symptoms depend on several factors, such as tumor location, size, growth rate, degree of invasion, and friability.4 Many of the symptoms are non-specific, particularly if the metastasis is not extensive.2 The most common symptom is dyspnea, followed by chest pain and B-symptoms (i.e., weight loss, fatigue, night sweats). Congestive heart failure with peripheral edema and pulmonary congestion characterizes 50% of clinical presentation. Cardiogenic shock, sudden cardiac death, acute myocardial infarction, and myocardial perforation have also been reported (Table 1).11

Due to its location in the right or left heart, a tumor embolization in the pulmonary or the systemic system can, respectively, occur.3

Direct infiltration or compression of coronary arteries is rare.12 If present, patients can experiment angina, also with troponin elevation (Table 1). Our patient had CT finding of epicardial involvement of coronary arteries too, but clinically silent.

The lymphomatous cells can infiltrate the electrical conduction system of the heart and determine electrocardiographic (ECG) abnormalities. Frequently, these include atrial arrhythmias and atrioventricular blocks. Other ECG alterations descripted are right bundle branch block, inverted T waves, low voltage, as well as life‐threatening ventricular tachyarrhythmia.13 The risk of sudden cardiac death is present. In particular, T-cell lymphomas seem to be more related to sudden cardiac death when compared to B-cell ones, because of a highest predisposition to infiltration.5

ECG as well as chest X-ray is not sensitive tool to recognize or suspect cardiac infiltration.14

In case of suspected cardiac involvement, trans-thoracic echocardiography is the first-line imaging modality.3 The typical features include right or left ventricular hypertrophy, and hypo- or akinetic areas where the infiltrative tumor grows. The infiltration can extend and modify epicardial and endocardial borders, as well as surround the peri-cardiac vessels.5 When the pericardium is involved, lymphomas may cause pericardial effusion, particularly hemorrhagic effusion, and cardiac tamponade.3

Our case is a rare presentation of a massive infiltration of both ventricles, with extension to the peri-aortic space. Only other few case reports displayed similar findings, with a recall to infiltrative-hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.6,9,10

Trans-esophageal echocardiography is an imaging technique potentially useful in these patients, but risky, due to the contiguity between the esophagus and the pericardium sac and the heart. Accordingly, even in our case, this approach was avoided.

Thanks to its tissue resolution, computed tomography (CT) can demonstrate the morphology, the location, and the extension of cardiac or mediastinal mass. The usual findings are single or multiple hypo- or iso-attenuating, variably enhancing mass.8 However, myocardial infiltration may be detected with CT (i.e., hypertrophic left ventricular septum). One of the disadvantages is the absence of real-time images.3 CT is the gold standard to stage the disease.

The preferred imaging modality is cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) because of better temporal and spatial resolution. The variable signal intensity is due to the cellularity of the neoplasm: tumor cells have a higher free-water content, so they commonly appear hypointense on T1-weighted MR sequences and hyperintense in T2. On contrast, late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) does not show specific pattern for cardiac lymphoma presenting as a mass (commonly minimal or no enhancement).

Finally, [18F]-Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography, biopsy of the bone marrow or, directly, of the mass, completes the evaluation and confirms tumor extension. Moreover, PET has recently been reported to detect clinically silent cardiac involvement.4

Despite the improvement of imaging tools, cardiac lymphoma has still a diagnostic delay because of a low index of suspicion and a rapid evolution.6Thus, the prognosis remains poor for both primary and secondary cardiac lymphoma. Four risk factors for a worse survival are: being immunocompromised, the presence of extracardiac disease, left ventricular involvement, and absence of arrhythmia.3,8 Usually, heart failure and sepsis are the common cause of death. Gordon et al. showed that the initial presentation had some impact on prognosis, with a median survival of 3 months.2 In general, the mean survival is about 12 months after diagnosis.3 However, other case series also displayed better survival thanks to modern chemotherapy schemes.8

No guidelines are available regarding treatment.4 The only effective therapy is chemotherapy and, in many cases, it has only palliative purposes.5 The therapeutic schemes include different combination of drugs, where the most used is CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone). Rituximab and monoclonal therapies are often administered.4 Usually, cardiac infiltration is sensitive to chemo- and radiotherapy.15 However, radiation is confined to cardiac masses that progress despite chemotherapy, because of cardiovascular side effects.4 In some case series, it is reported that the overall response rate of primary cardiac lymphoma to chemotherapy is 79% and complete remission is 59%. Similar results are shown for secondary lymphoma.16

Eventually, surgical excision is only addressed to exceptional cases (i.e., patient with heart valve obstruction and good estimated prognosis).5

Two points appear to be fundamental: early administration of chemotherapy and prevention of complication. Although rare, some fatal events may occur during the initiation of chemotherapy.4,8 Ventricular fibrillation, refractory heart failure, myocardial injury, and massive pulmonary embolism may complicate the management.17 Moreover, a theoretical risk of cardiac rupture is also reported, particularly in case of rapid tumor destruction. In fact, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is also known to potentially cause perforation of hollow organs (i.e., trachea and gastro-intestinal tract).18 Evidences from several case reports or retrospective case series show a dose reduction regimen or a chemotherapy delay to be effective in reducing complications (Table 1).8 However, because of the lack of strong recommendations, an individualized approach, based on clinical suspicion or concern, should be used19. A prophylactic placement of pericardial patch over the atrial free wall to protect against rupture has been described20,21,22,23,24.

In order to detect early complications, a multidisciplinary approach, involving different physicians (i.e., cardiologist, hematologist, cardiac surgeon), is suggested. The role of cardiovascular imaging is crucial as well as serial troponin measurement.

New Knowledge Gained

This review confirms that multimodal imaging assessment is crucial to diagnose cardiac lymphoma and to early detect the occurrence of complications. Since its suspect, cardiac lymphoma necessitates multidisciplinary interventions.

Conclusion

Primary cardiac lymphoma is a rare condition, while metastatic localization of lymphoma is more frequent.3 Although usually clinically silent, some non-specific symptoms may occur. In particular, our patient had electrical disturbances and sign and symptoms of congestion.

Multimodality imaging is helpful and confirmation with biopsy is mandatory. Once detected, the cardiac lymphoma necessitated early administration of chemotherapy.

The risk of complications during chemotherapy cycles is low, but still present. Serial echocardiographic testing, electrocardiographic monitoring, and evaluation of biomarkers (i.e., cardiac troponin) may help the clinician to find out complications, especially in the very first phases. It seems that a low-dose regimen, especially in the initial phases, may be safe and effective in the prevention of complications.

Early response to the drugs seems to be not infrequent, with relief of the symptoms. However, despite modern effective chemotherapy regimens, overall prognosis remains poor.

Abbreviations

- CMR:

-

Cardiac magnetic resonance

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- ECG:

-

Electrocardiogram

- IVUS:

-

Intravascular ultrasound

- LGE:

-

Late gadolinium enhancement

- NA:

-

Not available

- PCL:

-

Primary cardiac lymphoma

- PET:

-

Positron Emission Tomography

- TEE:

-

Trans-esophageal echocardiography

- TTE:

-

Trans-thoracic echocardiography

References

Grebenc ML, Rosado De Christenson ML, Burke AP, Green CE, Galvin JR (2000) Primary cardiac and pericardial neoplasms: Radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiographics.20.4.g00jl081073

Gordon MJ, Danilova O, Spurgeon S, Danilov AV (2016) Cardiac non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: Clinical characteristics and trends in survival. Eur J Haematol. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejh.12751

Jeudy J, Burke AP, Frazier AA (2016) Cardiac lymphoma. Radiol Clin N Am. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcl.2016.03.006

O’Mahony D, Peikarz RL, Bandettini WP, Arai AE, Wilson WH, Bates SE (2008) Cardiac involvement with lymphoma: A review of the literature. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma. https://doi.org/10.3816/CLM.2008.n.034

Vinicki JP (2013) Complete regression of myocardial involvement associated with lymphoma following chemotherapy. World J Cardiol. https://doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v5.i9.364

Fujisaki J, Tanaka T, Kato J et al (2005) Primary cardiac lymphoma presenting clinically as restrictive cardiomyopathy. Circ J. https://doi.org/10.1253/circj.69.249

Travis WD, Brambilla E, Nicholson AG et al (2015) WHO classification of tumours of the lung, pleura, thymus and heart. J Thorac Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1097/JTO.0000000000000630

Al-Mehisen R, Al-Mohaissen M, Yousef H (2019) Cardiac involvement in disseminated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, successful management with chemotherapy dose reduction guided by cardiac imaging: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases. https://doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i2.191

Kuchynka P, Palecek T, Lambert L, Masek M, Knotkova V (2018) Cardiac involvement in lymphoma mimicking hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Kardiol Pol. https://doi.org/10.5603/KP.2018.0167

Lau L, Mozolevska V, Kirkpatrick IDC, Jassal DS, Kansara R (2017) Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma mimicking cardiac amyloidosis. Clin Case Rep. https://doi.org/10.1002/ccr3.948

Cohen Y, Daas N, Libster D, Gillon D, Polliack A (2002) Large B-cell lymphoma manifesting as an invasive cardiac mass: Sustained local remission after combination of methotrexate and rituximab. Leuk Lymphoma. https://doi.org/10.1080/1042819022386699

Oder D, Topp MS, Nordbeck P (2020) Coronary B-cell lymphoma infiltration causingmyocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz538

Chen C-F, Hsieh P-P, Lin S-J (2017) Primary cardiac lymphoma with unusual presentation: A report of two cases. Mol Clin Oncol. https://doi.org/10.3892/mco.2017.1131

Faganello G, Belham M, Thaman R, Blundell J, Eller T, Wilde P (2007) A case of primary cardiac lymphoma: Analysis of the role of echocardiography in early diagnosis. Echocardiography. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-8175.2007.00472.x

Reynen K, Köckeritz U, Strasser RH (2004) Metastases to the heart. Ann Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdh086

Petrich A, Cho SI, Billett H (2011) Primary cardiac lymphoma: An analysis of presentation, treatment, and outcome patterns. Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.25444

Rolla G, Bertero MT, Pastena G et al (2002) Primary lymphoma of the heart. A case report and review of the literature. Leuk Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2126(01)00092-3

Vaidya R, Habermann TM, Donohue JH et al (2013) Bowel perforation in intestinal lymphoma: Incidence and clinical features. Ann Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdt188

Palaskas N, Thompson K, Gladish G et al (2018) Evaluation and management of cardiac tumors. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11936-018-0625-z

Molajo AO, Mcwilliam L, Ward C, Rahman A (1987) Cardiac lymphoma: An unusual case of myocardial perforation-clinical, echocardiographic, haemodynamic and pathological features. Eur Heart J. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a062317

Beckwith C, Butera J, Sadaniantz A, King TC, Fingleton J, Rosmarin AG (2000) Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma involving the heart: Case 1. Primary transmural cardiac lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2000.18.9.1996

Citron ML (2008) Dose-dense chemotherapy: Principles, clinical results and future perspectives. Breast Care. https://doi.org/10.1159/000148914

Shah K, Shemisa K (2014) A “low and slow” approach to successful medical treatment of primary cardiac lymphoma. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2223-3652.2014.04.01

Cereda AF, Moreo AM, Sormani P et al (2018) Impact of serial echocardiography in the management of primary cardiac lymphoma. J Saudi Hear Assoc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsha.2017.08.001

Wiernik PH (1976) Spontaneous regression of hematologic cancers. Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 44:35-8

Collazzo R, Guindani A, Pavan D, Zanuttini D (1987) Secondary neoplastic infiltration of the myocardium diagnosed by two-dimensional echocardiography in seven cases with anatomic confirmation. J Am Coll Cardiol. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0735-1097(87)80401-1

Cracowski JL, Trémel F, Nicolini F, Bost F, Mallion JM (1997) Localisation myocardique chimiosensible observee au cours d’un lymphome malin non Hodgkinien. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss 90:1527

Cho JG, Ahn YK, Cho SH et al (2002) A case of secondary myocardial lymphoma presenting with ventricular tachycardia. J Korean Med Sci. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2002.17.4.549

Bergler-Klein J, Knoebl P, Kos T et al (2003) Myocardial involvement in a patient with Burkitt’s lymphoma mimicking hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. https://doi.org/10.1067/j.echo.2003.08.013

Dawson MA, Mariani J, Taylor A, Koulouris G, Avery S (2006) The successful treatment of primary cardiac lymphoma with a dose-dense schedule of rituximab plus CHOP [4]. Ann Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdj005

Jonavicius K, Salcius K, Meskauskas R, Valeviciene N, Tarutis V, Sirvydis V (2015) Primary cardiac lymphoma: Two cases and a review of literature. J Cardiothorac Surg. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13019-015-0348-0

Sarr SA, Gaye AM, Aw F et al (2017) Obstructive primary cardiac t-cell lymphoma: A case report from senegal. Am J Case Rep. https://doi.org/10.12659/AJCR.901455

Cheng JF, Lee SH, Hsu RB et al (2018) Fulminant primary cardiac lymphoma with sudden cardiac death: A case report and brief review. J Formos Med Assoc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfma.2018.03.011

Bonou M, Kapelios CJ, Marinakos A et al (2019) Diagnosis and treatment complications of primary cardiac lymphoma in an immunocompetent 28-year old man: A case report. BMC Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-019-5405-y

Disclosures

Doctors Bonelli, Paris, Bisegna, Milesi, Gavazzi, Giubbini, Cattaneo, Facchetti, and Faggiano have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Brescia within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Funding

Doctors Bonelli, Paris, Bisegna, Milesi, Gavazzi, Giubbini, Cattaneo, Facchetti and Faggiano have no funding sources.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bonelli, A., Paris, S., Bisegna, S. et al. Cardiac lymphoma with early response to chemotherapy: A case report and review of the literature. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 29, 3044–3056 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12350-021-02570-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12350-021-02570-5