Summary

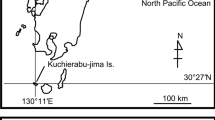

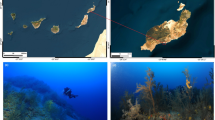

Providencia Island in the SW Carbbean is 4.5 to 8.5 km across (including Sta. Catalina Island). In contrast to nearby San Andrés, which is an elevated Tertiary atoll, Providencia is formed by an extinct Miocene volcano. This lies far off the Middle American mainland, and therefore its geological history is somewhat unique among other western Caribbean islands. The submarine basement of Providencia rises with steep to vertical slopes from an ocean sea floor of approximately 2,000 m depth. The island itself is rugged with peaks reaching up to more than 360 m above present sea-level. It is surrounded by a wide carbonate insular shelf protected towards the N,E and SE by the second largest barrier reef (after that of Belize) of the Caribbean Sea. The entire reef complex forms a carbonate shelf, which consists of a 32 km long windward bank-barrier reef with lagoonal environments in its lee, dotted with patch reefs and minor fringing reefs. Seaward of the barrier there is a wide fore-reef terrace dropping off to the upper island slope. In contrast, the leeward shelf, lagoon and coastal areas are unprotected to the open sea by major coral reefs and submarine showls, though minor reef structures resembling relics of a former barrier reef are present. Hence, the leeward environments are exposed against storm waves approaching from the West.

The submarine topography of the insular shelf is characterized by several lagoonal basins, up to 14 m deep, which may be partly of karstic origin. At water depths of 2–6m wide areas are occupied by extensive shallow lagoonal terraces. At least, two stream gullies continue from the island as submarine channels onto the insular shelf. A submerged elongate ridge in shelf-margin position is situated at more than 25 m of depth and may be a drowned shelf-edge barrier reef. These observations and the presence of submerged terraces indicate that the contemporary submarine topography of the modern reef complex has geomorphologic features inherited during lowered Pleistocene sea-level stands.

A major part of the barrier reef is formed by a wide belt consisting of numerous patch reefs, mostly of the pinnacle type, which rise from the sea floor at −6 to −8 m reaching to the low-tide level. Such discontinuous parts of the barrier reef may be from 100 up to 1,000 m wide. The continuous segments of the barrier reef are around 100 m wide and display well-developed groove-and-spur systems. Locally, segments of a continuous barrier are also present in front of the discontinuous reef belt. The reef crests and upper forereef are overgrown by luxuriantMillepora alcicornis with local patches ofAcropora palmata. Otherwise, the latter species is found mainly in front or behind the crest. Near the NW end of the barrier the outer margin of the reef flat is marked by a true algal ridge. The lagoonal patch reefs vary in shape, size and outline, and their crests are normally below 1 or 2 m water depth. They are characterized by thickets ofAcropora cervicornis in the E and by dense growths ofPorites furcata in the SE of the island. Calm-water associations withMontastraea annularis prevail at deeper and/or calmer lagoonal sites. Crests of unprotected shallow leeward reefs (‘Lawrance Reef’, ‘Pearstick Bar’) show dense growth ofAcropora palmata.

Providencia itself is a volcanic island formed by pre-Miocene(?) to Miocene lava flows, pyroclastics and epiclastic deposits. All of its pre-Miocene(?) to possibly very early Miocene effusives are of the rhyolitic type and seem to be submarine. Subsequent subaerial eruptions in Early to Upper Miocene time yielded large masses of basaltic to andesitic lavas and pyroclastics. As calculated from the dips of their volcanic bedding planes, the former rim of the central crater area may have emerged more than 1,000 m above the present sea-level in Upper Miocene time. Since then, the relief of the island gradually diminished by subaerial erosion aquiring its present aspect of a deeply eroded volcanic cone. The crater diametre was about 1 km. Intercalations of carbonates within the younger series of volcanic deposits reveal lagoonal deposits near its base and carbonate slope deposits interfingering with the higher volcanic strata. The lagoonal deposits are horizontally bedded tuffaceous carbonates, which yielded a soft-bottom coral fauna, burrowing echinoids and pelecypods signalling the first direct evidence of an early carbonate island shelf. The seaward-sloping higher strata contain massive and branching reef corals and large isolated oyster valves. The fossils suggest an Early to possibly Middle Miocene age of the carbonates.

The regional tectonic pattern of the Western Caribbean deep-sea floor is notable for its conspicuous fracture zones. It appears that the primitive submarine volcano of Providencia initiated in early Tertiary time along a tectonic fracture line paralleling the NNE trending San Andrés Trough to its E. It is assumed that the outflows of submarine(?) lavas along a fissure formed an elongated submarine volcanic ridge in fairly shallow water. By Miocene time, subsidence compensated by shallow water carbonate sedimentation and upgrowth of coral reefs lead to the formation of a carbonate platform, most likely of the coral bank or atoll type. It probably showed already the approximate outline and size as the present insular shelf. A second period of volcanic activity in Early to Late Miocene yielded basaltic to andesitic lavas and pyroclastics during several major subaerial eruptions. These formed five conspicuous volcanic tongues, which radiate to the sea from a crater area in the centre of the island.

The early eruptive phase was probably contemporaneous with the formation of several additional shallow submarine volcanos in the Western Caribbean. They appear equally bound to fracture lines on the sea-floor. These volcanic structures are deeply submerged today and capped by thick limestone deposits forming the remaining atolls and islands of the archipelago. Of these, only nearby San Andrés was uplifted in latest Tertiary times thus revealing today its Miocene reef and lagoonal deposits. But, in contrast to Providencia, in none of these was there a second period of eruptive activity in late Tertiary times to form a long-living emergent volcanic build-up.

Quaternary sea-level oscillations are indicated by subaerial and submarine terraces cut into coastal limestone by advancing sea cliffs. There is a relic of an erosional terrace at +50–60 m in the Miocene limestone, probably of Early or Middle Pleistocene age. The wide fore-reef terrace with its outer margin at depths around −20 to −40 m indicates a prolonged low sea-level stand of pre-Sangamonian age. A fossil fringing reef terrace of Sangamonian age, reaches a maximum elevation of about +3 m above present sea-level. The fossil coral associations of this reef indicate an environment fairly protected from major waves. Thus, it may be assumed that the contemporary outer reef barrier protecting the island coast reached more than 3 m above the present sea-level. In addition there is evidence that the coral associations of the fossil reef lived in water depths possibly near 10 m. The very shallow terraces situated in front of the active limestone cliffs and around certain patch reefs were formed by planation towards the end of the Holocene transgression.

Size and shape of the island changed periodically during Pleistocene sea-level fluctuations. Due to the high and relatively steep island relief, the Pleistocene high sea-level recorded by the ’+50–60 m—Terrace’ would not have submerged more than about 35% of the present land surface area. With the exception of the flooding of the coastal low-lands and some deeper valleys and the formation of smaller satellite islands by temporarily isolating some of the higher headlands, the configuration of Providencia did not undergo any essential change. By contrast, during low stands (−25 to −120 m) that followed the great Sangamonian transgression until the Wisconsinian stage, the total of the extensive island shelf was almost permanently emergent for a period of more than 100,000 years. Geomorphologically, the reef complex appeared as an elongated limestone table mountain bounded by sheer cliffs which rose more than 100 m above sea-level. During this period the emergent insular shelf formed an extended northern prolongation of the original volcanic island. The entire island measured some 30 km in length in Wisconsinian times, and its surface area totalled roughly 12 times that of the present island.

From the evidence above we may draw the preliminary conclusion that the existence of an insular shelf can be traced back at least to Miocene time. The contemporary shelf morphology is the product of a complex history of sea-level oscillations accompanied by terracing at different levels, renewed reef growth and erosion. Of this history, at present, only a few evolutionary stages may be recognized. Volcanic activity did not contribute to the geomorphologic evolution of the island and shelf in post-Miocene time. The shelf was last exposed to subaerial weathering during the sea-level lowering that accompanied the late Wisconsin glaciation. It appears that since reflooding in the early Holocene some 5,000 years ago, renewed reef growth and sedimentation have only partly concealed or modified the pre-existing shelf topography.

Zusammenfassung

Die Insel Providencia im südwestlichen Karibischen Meer erreicht einen Durchmesser von 4,5 bis 8,5 km (einschließlich Sta. Catalina). Im Gegensatz zur nahegelegenen Insel San Andrés, einem herausgehobenen tertiären Atoll, wird sie von einem erloschen miozänen Vulkan gebildet. Dieser liegt fern vom Festland und ist deshalb etwas ungewöhnlich unter den karibischen Inseln. Das untermeerische Fundament der Insel Providencia steigt steil bis senkrecht von einem ozeanischen Meeresboden in rund 2 000 m Tiefe auf. Die Insel selbst erhebt sich mit zackigen Spitzen mehr als 360 m über den heutigen Meeresspiegel. Sie wird von einem breiten Insularschelf umgeben, der gegen N, E und S durch das zweigrößte Wallriff (nach Belize) des Karibischen Meeres geschützt wird. Der gesamte Riffkomplex bildet einen Karbonatschelf bestehend aus einem 32 km langen luvseitigen Wallriff und den in seinem Lee gelegenen Lagunenablagerungen mit Fleckenriffen und kleineren Saumriffen. Seewärts des Wallriffes liegt eine breite Vorriff-Terrasse, welche jäh von dem steilen bis senkrechten Insularabhang abgelöst wird. Im Gegensatz hierzu werden weder der leeseitige Schelf noch die leeseitigen Lagunen-und Küstenbereiche von größeren Riffen und Untiefen gegen das offene Meer geschützt, obwohl es auch hier kleinere Riffe gibt, welche wie Relikte eines einstigen Wallriffes erscheinen. Folglich sind die leeseitigen Milieus den winterlichen Sturmwellen aus westlichen Richtungen besonders ausgesetzt.

Die submarine Topographie des Insularschelfes zeigt charakteristischerweise mehrere bis zu 14 m tiefe Lagunenbecken, welche teilweise durch Verkarstung entstanden sein könnten. Weite Gebiete werden von ausgedehnten Lagunen-Terrassen in 2–6 m Tiefe eingenommen. Wenigstens zwei Bachrisse lassen sich von der Insel über den Insularschelf als submarine Rinnen verfolgen. Ein untermeerischer Rücken am nordöstlichen Schelfrand in etwas mehr als 25 m Wassertiefe scheint ein ertrunkenes Schelfkanten-Wallriff zu sein. Diese Beobachtungen und das Vorkommen weiterer untergetauchter Terrassen zeigen, daß die heutige submarine Topographie des rezenten Riffkomplexes geomorphologische Merkmale aufweist, welche während Meeresspiegel-Tiefständen im Pleistozän erworben wurden.

Ein Großteil der Riffbarriere wird von einem breiten Gürtel aus dichtstehenden Turmriffen gebildet, welche sich aus 6 bis 8 m Tiefe bis an den Niedrigwasserspiegel erheben. Gerüstbildner sind vor allemMillepora alcicornis, aber auchAcropora palmata undMontastraea annularis. Solche unzusammenhängenden Abschnitte des Wallriffes können 100 bis 1000 m breit werden. Die zusammenhängenden Abschnitte der Riffbarriere sind gegen 100 m breit und besitzen ein wohlausgebildetes Brandungsrinnensystem. Stellenweise finden sich Teilstücke einer zusammenhängenden Barriere noch zusätzlich vor dem unzusammenhängenden Riffgürtel. Der Riffkamm des zusammenhängenden Wallriffes ist von einem üppigen Wuchs vonMillepora alcicornis bedeckt, zu dem stellenweise nochAcropora palmata-Hecken treten, welche sonst hauptsächlich vor und hinter dem Riffkamm siedeln. Nicht weit vom NW-Ende des Wallriffes hat sich am Außenrand der Riffplatte ein echter Kalkalgenwall gebildet. Die Fleckenriffe in der Lagune sind mannigfaltig in Bezug auf ihre Form, Größe und Umriß. Ihre Riffkämme reichen nicht flacher als 1 bis 2 m und werden charakteristischerweise vonAcropora cervicornis-Hecken im E und von dichtstehenden Kolonien der FingerkorallePorites furcata im SE der Insel überwachsen. Ruhigwasser-Vergesellschaftungen mitMontastraea annularis herrschen an tieferen und/oder geschützteren Lagunenlokalitäten vor. Kämme von ungeschützten Flachwasser-Riffen der Leeseite (‘Lawrance Reef’, ‘Pearstick Bar’) zeigen dichten Bewuchs durchAcropora palmata.

Providencia selbst ist eine Vulkaninsel, welche von prämiozänen (?) bis miozänen Lavaergüssen, Pyroklastika und epiklastischen Ablagerungen gebildet wird. Alle prä-miozänen(?) bis möglicherweise sehr früh-miozänen Effusiva sind von rhyolithischem Typus und scheinen submarin zu sein. Nachfolgende subaerische Eruptionen im frühen bis oberen Miozän haben große Mengen von basaltischen bis andesitischen Laven und Pyroklastika gefördert. Aus dem Einfallen der Vulkanitlagen läßt sich die ungefähre Höhe des früheren Kraterrandes ermitteln. Dieser hätte demnach im Obermiozän mehr als 1000 m über den heutigen Meeresspiegels geragt. Seither hat sich das Relief allmählich durch subaerische Erosion verflacht, und die Insel hat das heutige Aussehen eines tief erodierten Vulkankegels angenommen. Der Krater besaß ungefähr 1 km Durchmesser. Als Einschaltungen treten in der jüngeren Vulkanit-Serie lokal Flachwasserablagerungen auf. Es sind dies tuffhaltige Lagunen-Ablagerungen mit einer Weichboden-Korallenfauna, grabenden Seeigeln und Pelecypoden, welche erstmals direkt einen frühen karbonatischen Insularschelf belegen. Darüber folgen karbonatische Hangablagerungen mit massigen und verzweigten Riffkorallen und einzelnen Austernklappen von frühem bis wahrscheinlich mittelmiozänem Alter.

Das regionale Tektonik-Muster des Tiefseebodens des westlichen Karibischen Meeres zeigt auffallende Bruchzonen. Es scheint, daß der primäre untermeerische Vulkan von Providencia im frühem Tertiär entlang einer tektonischen Bruchlinie entstand, welche parallel zu dem sich in NNE-Richtung erstreckenden San Andrés-Trog verläuft. Man kann annehmen, daß die entlang einer Spalte ausfließenden untermeerischen(?) Laven einen länglichen vulkanischen Rücken in ziemlich flachem Wasser bildeten. Der Chemismus dieser Effusiva war sauer und von rhyolithischem Typus. Bis zum Miozän haben die Sedimentation von Flachwasserkarbonaten und das Hochwachsen von Korallenriffen auf dem vulkanischen Rücken bei gleichzeitiger Subsidenz zur Bildung einer Karbonatplattform, höchstwahrscheinlich vom Korallenbank-Typ oder Atoll-Typ geführt. Diese hatte wahrscheinlich bereits einen ähnlichen Umriß und ähnliche Größe wie der heutige Insularschelf. Eine zweite Eruptionsperiode im frühen bis späten Miozän förderte basaltische sowie andesitische Laven und Pyroklastika während mehrerer größerer subaerischer Eruptionen. Diese Vulkanite wurden hauptsächlich in 5 auffallenden Zungen abgelagert, welche von einem zentralen Krater in Inselmitte radial nach allen Richtungen in Richtung Meer auslaufen. Zu Beginn waren diese Eruptionen besonders heftig, indem sie einen Teil der älteren geschichteten, rhyolithischen Ablagerungen hochpreßten, so daß diese heute großflächig, aber verstellt im Inselinneren anstehen. Zudem tritt ein Teil dieses älteren rhyolithischen Materiales als Komponenten der vulkanischen Breccien der jüngeren Periode auf. Die jüngeren Eruptionen waren örtlich beschränkt auf das Südende des alten vulkanischen Rückens, welcher das Fundament der miozänen Korallenbank bildet. Anscheinend war der im N des tätigen Vulkans gelegene Teil der Korallenbank nicht langfristig von den vulkanischen Immissionen betroffen und konnte sich als Atoll-ähnliche Struktur weiterentwickeln. Die meisten der Flachwasser-karbonate, welche sich mit den jüngeren Vulkaniten verzahnen und heute auf der Insel aufgeschlossen sind, wurden während der Burdigal-Transgression abgelagert. Zusammen mit der Subsidenz ergibt der scheinbare Meeresspiegelanstieg einen Betrag von wahrscheinlich mehr als 150 m. Außerdem läßt die heutige Höhenlage des Kalkes auf etwas tektonische Heraushebung im Post-Burdigal schließen. Die primäre rhyolithische Eruptionsphase der Insel erfolgte anscheinend zeitgleich mit der Bildung von mehreren weiteren flachmarinen Vulkanen im westlichen Karibischen Meer, welche gleichfalls an Bruchlinien am Meeresboden gebunden waren. Auch diese vulkanischen Strukturen wurden durch Subsidenz tief abgesenkt und von mächtigen Karbonaten überlagert, so daß sich Atolle oder Guyots bildeten. Von diesen tertiären Atollen wurde allein San Andrés im jüngsten Tertiär weit genug herausgehoben, daß heute hier miozäne Riff- und Lagunenablagerungen in Aufschlüssen zugänglich sind. Im Gegensatz zu Providencia erfolgte bei keinem dieser miozänen Atolle eine zweite Eruptionsphase, welche eine langlebige Vulkaninsel hätte aufbauen können.

Hinweise für quartäre Meeresspiegelschwankungen sind subaerische und submarine Terrassen, welche in Kalkstein durch vorrückende Küstenkliffs geschnitten wurden. Es gibt ein Terrassenrelikt in +50–60 m Höhe, eingeschnitten in den miozänen Kalk und eine fossile Saumriffterrasse, welche sich maximal rund +3 m über den heutigen Meeresspiegel erhebt. Das absolute Alter dieses Riffes ist ca. 120 000 Jahre und damit in das Sangamon-Interglazial (=Riß-Würm-Interglazial, Eem) zu stellen. Die fossile Korallenassoziation weist auf ein Milieu hin, das ziemlich gut vor größeren Wellen geschützt war. Folglich kann man annehmen, daß die frühere äußere Riffbarriere, welche die Küste der Insel schützte, mehr als etwa 3 m höher als der heutige Meeresspiegel gereicht hat. Außerdem gibt es Hinweise dafür, daß die Korallenassoziationen des fossilen Riffes in Wassertiefen nahe 10 m lebten. Die breite Vorriff-Terrasse mit ihrem Außenrand in Wassertiefen um −40 bis −20 m ist ein Indiz für einen längeren Meeresspiegel-Tiefstand von Prä-Sangamon-Alter. Die sehr flachliegenden Terrassen (−4 bis −2 m) vor den aktiven Kalksteinkliffen und um bestimmte Fleckenriffe herum wurden durch Einebnung gegen Ende der holozänen Transgression gebildet.

Die Form und Größe der Insel wechselten periodisch während pleistozänen Meeresspiegelschwankungen. Infolge des hohen und verhältnismäßig steilen Reliefs der Insel, dürfte der pleistozäne Meeresspiegelhochstand, der durch die +50–60 m—Terrasse markiert wird, nicht mehr als 35% der gegenwärtigen Landoberfläche unter Wasser gesetzt haben. Mit Ausnahme der Überflutung der schmalen Küstenebenen und tiefgelegenen Tälern sowie der Bildung von kleineren Satelliten-Inseln durch vorübergehendes Abtrenen einiger der höher aufragenden Küstenvorsprünge, wurde die Gesamtform von Providencia grundsätzlich nicht sehr stark verändert. Im Gegensatz hierzu fiel während der Meeresspiegel-Tiefstände (−25 bis −120 m), welche auf die große Sangamon-Transgression folgten und welche bis zum Ende des Wisconsin-Glazials (=Würm-Eiszeit) andauerten, der gesamte ausgedehnte Insularschelf über eine Zeitraum von mehr als 100 000 Jahren fast ununterbrochen trocken. Der damals aufragende Riffkomplex erschien deshalb während dieses Zeitraumes als länglicher Tafelberg aus Kalkstein mit einer bis über 100 m hohen, steilen bis senkrechten Kliffküste. Dieser Tafelberg bildete eine beträchtliche Verlängerung der ursprünglichen Insel nach N. Damals erreichte Providencia rund 30 km Länge, und die Landoberfläche war ungefähr 12 mal größer als diejenige der heutigen Insel.

Aus den obigen Beobachtungen können wir den vorläufigen Schluß ziehen, daß sich die Entwicklung eines Insularschelfes zumindest bis ins Miozän zurück verfolgen läßt. Die heutige Schelfmorphologie ist Ergebnis einer komplexen Geschichte von Meeresspiegelschwankungen, welche von Terrassenbildungen, Riffwuchs und Erosion in verschiedenen Höhen- und Tiefenlagen begleitet war. Von dieser Entwicklungsgeschichte lassen sich gegenwärtig nur einige wenige Entwicklungsstadien sicher rekonstruieren. Der Vulkanismus hat im Post-Miozän nicht mehr zur geomorphologischen Entwicklung von Insel und Insularschelf beigetragen. Der Insularschelf war zum letzten Mal der subaerischen Verwitterung während der Meeresspiegelabsenkung des Wisconsin-Glazials (Würm-Eiszeit) ausgesetzt. Es scheint, daß seit der erneuten Überflutung im frühen Holozän vor rund 5 000 Jahren erneuter Riffwuchs und Sedimentation die überlieferte Schelf-Topographie nur unvollständig verändert und verdeckt haben.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Adey, W.H. &Burke, R.B. (1976): Holocene bioherms (algal ridges and bank-barrier reefs) of the eastern Caribbean.—Bull. geol. Soc. Amer.,84, 95–109, 15 figs., Washington, D.C.

Antonius, A. (1982): The ‘band’ diseases in coral reefs.—Proc. Fourth int. Coral Reef Symp. (Manila, 1981)2, 7–14, 16 figs., 2 tables, Quezon City

Arden, D.D. (1969): Geologic history of the Nicaraguan Rise— Trans. Gulf Coast Assoc. geol. Socs.19 295–309, 8 figs., Miami Beach

Bak, R.P.M. &Criens, S.R. (1982): Experimental fusion in AtlanticAcropora (Scleractinia).—Marine Biol. Letters3, 67–72, 1 table, Amsterdam

Barnwell, F.H. (1975): External annual growth bands in the Caribbean hydrocoralMillepora complanata.—Chronobiologia2(suppl. 1) 6, Milano, publications pertinent to the archipelago

Barriga-Bonilla, E., Hernández-Camacho, J., Jaramillo, T.I., Jaramillo-Mejía, R., Mora-Osejo, L.E., Pinto-Escobar, P., &Ruiz-Carranza, P. (1969): La Isla de San Andrés. Contribuciones al conocimiento de su ecología, flora, fauna y pesca.—152 p., 4+31 figs., 5 foldouts, 6 tables, Universidad Nacional, Dirección de Divulgación Cultural, Bogotá, publications pertinent to the archipelago

Bartsch, P. &Rehder, H.A. (1939): Mollusks collected on the Presidential Cruise of 1938.—Smithsonian miscellan. Coll.98/10, 1–18, 5 pls., Washington, publications referring directly to Providencia

Bayer, F.M. (1961): The shallow-water Octocorallia of the West Indian region—Stud. Fauna Curaçao and other caribb. Islands12, 373 p., 27 pls., 101 figs., 3 tables, The Hague, publications referring directly to Providencia

Ben-Tuvia, A. &Ríos, C.E. (1970): Informe de un crucero del B/I Chocó a la Isla de Providencia y los bancos adyacentes de Quitasueño y Serrana en territorios insulares de Colombia.— PNUD-FAO-INDERENA, Communicaciones1/2, 9–45, 9 figs., 9 tables, Bogotá, publications referring directly to Providencia

Bowen, D.Q. (1988): Quarternary geology. A stratigraphic framework for multidisciplinary work.—234 pp., Oxford (Pergamon)

Bowland, Ch.L. (1984): Seismic stratigraphy and structure of the western Colombian Basin, Caribbean Sea.—M.S. thesis, University of Texas at Austin, 247 p. (only abstract seen)

Bowland, Ch.L. &Rosencrantz, E. (1988): Upper crustal structure of the western Colombian Basin, Caribbean Sea.—Bull. geol. Soc. America100, 534–546, 12 figs., Washington

Budd, A.F., Johnson, K.G. &Edwards, J.C. (1989): Miocene coral assemblages in Anguilla, B.W.I., and their implications for the interpretation of vertical succession on fossil reefs.—Palaios4, 264–275, 9 Figs., 3 tables, 1 appendix, Tulsa

Burgess, G.H. (1978): Zoogeography and depth analysis of the fishes of Isla de Providencia and Grand Cayman Island.— M.Sc. Thesis, Univ. Florida, Gainesville, 109 p. (unpublished, not seen), publications referring directly to Providencia

Burke, R.B. (1982): Reconnaissance study of the geomorphology and benthic communities of the outer barrier reef platform, Belize.—In:Rützler, K. &Macintyre, I.G. (eds.). The Atlantic barrier reef ecosystem at Carrie Bow Cay, Belize. I. Structure and communities (pp. 509–526, figs. 221–226), Smithsonian Institution, Washington

Cabrera-Ortíz, W. (1980): San Andrés y Providencia. Historia. —175 p., Bogotá, (Cosmos), publications referring directly to Providencia

Christofferson, E. &Hamil, M.M. (1978): A radial pattern of seafloor deformation in the southwestern Caribbean Sea.— Geology6, 341–344, 2 figs., Boulder, publications pertinent to the archipelago

Clark, A.H. (1939): Echinoderms (other than holothurians) collected on the Presidential Cruise of 1938.—Smithsonian miscellan. Coll.98/11, 1–18, 5 pls. Washington, publications referring directly to Providencia

Collett, C.F. (1837): On the island of Old Providence.—J.r. geogr. Soc. London7, 303–310, London publications referring directly to Providencia

Concha-Perdomo, A.-E. (1989): Geochemisch-petrologische Untersuchungen an Vulkaniten der kolumbianischen Insel Providencia/Karibik.—PhD Dissertation, pp. i-iii+1-140, 51 figs., 3 tables, 5 appendices, Johannes-Gutenberg-Universität, Mainz (unpublished), publications referring directly to Providencia

Conchia, A.-E. & Macia, C. (1992): Clasificación geoquímica de las rocas volcánicas de Providencia en el Caribe Colombiano.—manuscript submitted to Geología colombiana, Bogotá, publications referring directly to Providencia

Cortés-N., J. &Risk, M. (1985): A reef under siltation stress: Cahuita, Costa Rica.—Bull. marine Sci.36/2, 339–356, 8 figs., 5 tables, Miami

Coventry, G.A. (1944): Results of the Fifth George Vanderbilt Expedition (1941). The Crustacea.—Acad. nat. Sci. Philadelphia, Monogr.6, 531–544, Philadelphia, publications referring directly to Providencia

Darwin, Ch. (1851): The structure and distribution of coral reefs. (Reprinted by University of California Press, Berkeley & Los Angeles 1962, IX+214 p., 5 figs., 3 pls.), publications referring directly to Providencia

Dt. Hydr. Inst. (1989): Westindien-Handbuch I. Teil: Die Nordküste Süd- und Mittelamerikas, 370 p., numerous figs., maps etc., Deutsches Hydrographisches Institut, Publ. Nr. 2048, Hamburg, publications pertinent to the archipelago

Exquemelin, A.O. (1678): De Americaensche Zee-Roovers.—Jan ten Hoorn, Amsterdam. (New edition and German translation, 1969: Das Piratenbuch von 1678. Die amerikanischen Seeräuber, 265 p., Tübingen (Erdmann), publications referring directly to Providencia

Faye, S. (1941): Commodore Aury.—Louisiana historical Quarterly24, 611–697, New Orleans, publications referring directly to Providencia

Fowler, H.W. (1944): The fishes.—In: Results of the Fifth George Vanderbilt Expedition (1941).—Acad. nat. Sci. Philadelphia, Monogr.6, 57–529, 268 figs., 20 pls., Philadelphia, publications referring directly to Providencia

Fowler, H.W. (1950): Results of the Catherwood-Chaplin West Indies Expedition, 1948. Part. III. The fishes.—Proc. Acad. nat. Sci. Philadelphia,102, 69–93, 43 figs., Philadelphia, publications referring directly to Providencia

Frost, S.H. (1977): Miocene to Holocene evolution of Caribbean Province reef-building corals.—Proc. Third int. Coral Reef Symp. (Miami 1977)2 (Geology), 353–359, 3 figs., Miami

Garzón, F.J. &Acero, P.A. (1983): Notas sobre la pesca y los peces comerciales de la Isla de Providencia (Colombia), incluyendo nuevos registros para el Caribe occidental.— Caribb. J. Sci.19/3–4, 9–19, 1 table, Mayagüez, publications referring directly to Providencia

Geister, J. (1972a): Zur Oekologie und Wuchsform der SäulenkoralleDendrogyra cylindrus Ehrenberg. Beobachtungen in den Riffen der Insel San Andrés (Karibisches Meer, Kolumbien). —Mitt. Inst. colombo-alemán Invest. cient.6, 77–87, 2 figs., 2 pls., Sta. Marta, publications pertinent to the archipelago

Geister, J. (1972b): Nota sobre la edad de las calizas coralinas del Pleistoceno marino en las Islas de San Andrés y Providencia (Mar Caribe Occidental, Colombia).—Mitt. Inst. colomboalemán Invest. cient.6, 35–140, 2 figs., Sta. Marta, publications referring directly to Providencia

Geister, J. (1973a): Los arrecifes de la Isla de San Andrés (Mar Caribe, Colombia).—Mitt. Inst. colombo-alemán Invest. cient.7, 211–228, 1 fig. 3 pls. Sta. Marta, publications pertinent to the archipelago

Geister, J. (1973b): Pleistozäne und rezente Mollusken von San Andrés (Karibisches Meer, Kolumbien) mit Bemerkungen zur geologischen Entwicklung der Insel.—Mitt. Inst. colomboalemán Invest. cient.7, 229–251, Sta. Marta, publications pertinent to the archipelago

Geister, J. (1975): Riffbau und geologische Entwicklungsgeschichte der Insel San Andrés (westliches Karibisches Meer, Kolumbien).—Suttgarter Beitr. Naturk, Ser. B (Geol. & Paläont.)15, 1–203, 29 figs., 11 tables, 11 pls., Stuttgart, publications pertinent to the archipelago

Geister, J. (1977a): The influence of wave exposure on the ecological zonation of Caribean coral reefs.—Proc. Third int. Coral Reef Symp. (Miami 1977)1 (Biology), 23–29, 1 fig., Miami, publications referring directly to Providencia

Geister, J. (1977b): Occurrence ofPocillopora in Late Pleistocene Caribbean coral reefs.—Second Symposium international sur les coraux et récifs coralliens fossiles (Paris 1975).—Mém. Bur. Rech. géol. min.89, 378–388, 1 fig., 4 pls., Paris, publications pertinent to the archipelago

Geister, J. (1978): Recent coral reefs and geologic history of Providencia Island (western Caribbean Sea, Colombia).— Segundo Congr. colombiano Geol. (Bogotá 1978), 22 p., 1 fig., 7 pls. (unpublished manuscript), publications referring directly to Providencia

Geister, J. (1980a): Morphologie et distribution des coraux dans les récifs actuels de la mer des Caraibes.—Ann. Univ. Ferrara (N.S.) Sez. IX (Sci. geol. & paleont.) Vol.VI (Suppl.), 15–37, 4 figs., 4 pls., Ferrara, publications referring directly to Providencia

Geister, J. (1980b): Calm-water reefs and rough-water reefs of the Caribbean Pleistocene.—Acta palaeont. polon.25/3–4, 541–556, 7 figs., pls. 50–53, Warszawa, publications referring directly to Providencia

Geister, J. (1983): Holozäne westindische Korallenriffe: Geomorphologie, Oekologie und Fazies.—Facies9, 173–284, 57 figs., pls 25-35, 8 tables, Erlangen, publications referring directly to Providencia

Geister, J. (1984a): Récifs pléistocènes de la mer des Caraïbes: aspects géologiques et paléoécologiques.—In:Geister, J. & Herb, R. (eds.): Géologie et paléoécologie des récifs (3.1–3.34, 21 figs.), Institute de Géologie de l’Université de Berne, publications referring directly to Providencia

Geister, J. (1984b): Die paläobathymetrische Verwertbarkeit der scleractinen Korallen.—Paläontol. Kursbücher2, 46–95, 16 figs., München.

Gilbert, C.R. &Burgess, G.H. (1986): Variation in Western Atlantic gobiid fishes of the genusEvermannichthys.—Copeia1986/1, 157–165, 2 figs., 1 pl., Washington, publications referring directly to Providencia

Ginsburg, I. (1939): Two new gobioid fishes collected on the Presidential Cruise of 1938.—Smithsonian miscellan. Coll.98/14, 1–5, 2 figs., Washington, publications referring directly to Providencia

Glynn, P.W. (1984): Widespread coral mortality and the 1982–83 El Niño warming event.—Environmental Conservation11/2, 133–146, 8 figs., 4 tables, Lausanne

Göbel, V.W. (1985): On the Miocene volcanism of Providencia Island, Colombia, Western Caribbean.—Abstracts with programs.—Geol. Soc. Amer., South Central Section, 19th ann. Meeting, Fayetteville 198517/3, p. 159. publications referring directly to Providencia

Gómez, N. &Orozco, J.J. (1982): Petrografía de las rocas volcánicas de Providencia.—Tesis de grado, Universidad Nacional, Bogotá (unpublished, not seen), publications referring directly to Providencia

Gómez, D.P. &Victoria, P. (1980): Inventario preliminar de los peces de la Isla de San Andrés y noreste de la Isla de Providencia (Mar Caribe de Colombia).—Tesis de grado, Universidad Jorge Tadeo Lozano, Bogotá. (unpublished, not seen), publications referring directly to Providencia

Gordon, A. (1966): Caribbean Sea-Oceanography.—In:Fairbridge, Rh.W. (ed.): The encyclopedia of oceanography.—Encyclopedia of Earth Science Series, Vol.1, (p. 175–181, 5 figs.), New York, (Reinhold)

Hallock, P., Hine, A.C., Vargo, G.A., Elrod, J.A. &Jaap, W.C. (1988): Platforms of the Nicaraguan rise: Examples of the sensitivity of carbonate sedimentation to excess trophic resources.—Geology16, 1104–1107, 4 figs., Boulder

Haq, B.L., Hardenbol, J. &Vail, P.R. (1987): The new chronostratigraphic basis of Cenozoic and Mesozoic sealevel curves.—Special Publ. Cushman Foundation of Foraminiferal Research, No.24, 7–13, 4 figs., Washington

Holcombe, T.L., Ladd, J.W., Westbrook, G., Edgar, N.T. &Bowland, C.L. (1990): Caribbean marine geology: ridges and basins of the plate interior.—In:Dengo, G. &Case, J.E. (eds.): The Geology of North America. Vol.H, The Caribbean Region. —pp.231–306, 14 figs., Boulder, (The Geological Society of America), publications pertinent to the archipelago

Hubach, E. (1956): Aspectos geográficos y geológicos y recursos de las Islas de San Andrés y Providencia.—Cuademos de Geografía de Colombia12, 1–39, 3 maps, Bogotá, publications referring directly to Providencia

Invemar (1981): Informe sobre los resultados de la Expedición Providencia I a las Islas de Providencia, y Santa Catalina (Colombia).—117 p., Anexos 1–4, Instituto de Investigaciones Marinas de Punta de Betín (INVEMAR), Sta. Marta, publications referring directly to Providencia

Keeley, F.J. (1931): Pinchot Expedition, 1929: Notes on some volcanic rocks.—Proc. Acad. nat. Sci. Philadelphia,82 (1930), 139–141, Philadelphia, publications referring directly to Providencia

Kerr, J.M. Jr. (1978): The volcanic and tectonic history of La Providencia Island, Colombia.—M.S. Thesis, 52 p., 6 figs., 8 pls., 2 tables, appendices A+B, Rutgers-The State University, New Brunswick (unpublished) publications referring directly to Providencia

Laborel, J. (1969): Les peuplements de madréporaires des côtes tropicales du Brésil.—Ann. Université d’Abidjan 1969, Sér. E II, fasc.3, 261 p., 71 figs., Abidjan

Laubenfels, M.W. de (1939): Sponges collected on the Presidential Cruise of 1938.—Smithsonian miscellan. Coll.98/15, 1–7, 1 fig., Washington

Leão, Z.M.A.N. (1982): Morphology, geology and developmental history of the southermmost coral reefs of Western Atlantic, Abrolhos Bank, Brazil.—Diss. Univ. Miami, 216 p., 10 pls

Lessios, H.A. (1988): Mass mortality ofDiadema antillarum in the Caribbean: What we have learned?—Ann. Rev. Ecol. Syst.19, 371–393, 1 fig., 1 table, Palo Alto

Lessios, H.A., Robertson, D.R. &Cubit, J.D. (1984): Spread ofDiadema mass mortality through the Caribbean.—Science226, 335–337, 2 figs., New York

Lewis, J.B. (1991): Banding, age and growth in the calcareous hydrozoanMillepora complanata Lamarck.—Coral Reefs9/4, 209–214, 5 figs., 3 tables, Berlin

Loboguerrero, M.J. (1954): Sinopsis geográfica del Archipiélago de San Andrés y Providencia.—Bol. Soc. geogr. Colombia,12/3–4, 193–209, 14 figs., Bogotá, publications referring directly to Providencia

Macintyre, I.G. (1972): Submerged reefs of eastern Caribbean.— Bull. amer. Assoc. Petroleum Geol.56/4, 720–738, 8 figs., 2 tables, Tulsa

Macintyre, I.G., Burke, R.B. &Stuckenrath, R. (1982): Core holes in the outer fore-reef off Carrie Bow Cay, Belize: a key to the Holocene history of the Belizean barrier reef complex. —Proc. 4th. int. Coral Reef Symp. (Manila, 1981)1, 567–574, 5 figs., Quezon City

Malfait, B.T. &Dinkelman, M.G. (1972): Circum-Caribbean tectonic and igenous activity and the evolution of the Caribbean Plate. Bull. geol. Soc. America83, 251–272, 9 figs., Boulder

Mann, P., Schubert, C. &Burke, K. (1990): Review of Caribbean neotectonics.—InDengo, G. &Case, J.E. (eds.): The Geology of North America, Vol. H: The Caribbean Region.—pp.307–338, 3 figs., 3 tables, pl. 11, Boulder (The Geological Society of America)

Márquez-C., G. (1987): Las Islas de Providencia y Santa Catalina. Ecología regional.—110p., 17 figs., 32 coloured photographs, 3 maps, 1 table, Bogotá (Fondo FEN Colombia & Universidad Nacional de Colombia), publications referring directly to Providencia

McBirney, A.R. &Williams, H. (1965): Volcanic history of Nicaragua.—Publ. geol. Sci. (Univ. California))55, 1–73, Berkeley

Melendro, E. &Torres, M.L. (1985): Crustáceos decápodos de aguas someras de las Islas Vieja Providencia y Sta. Catalina (13°20′N y 81° 22′W) Colombia.—Tesis de grado, Universidad Jorge Tadeo Lozano, Bogotá, (unpublished, not seen), publications referring directly to Providencia

Milliman, J.D. (1969a): Four southwestern Caribbean atolls: Courtown Cays, Albuquerque Cays, Roncador Bank and Serrana Bank.—Atoll Res. Bull.129, 1–41, figs. 1–10+A1–A7, 13 pls., tables 1–4+A1–A2, Washington, publications pertinent to the archipelago

Milliman, J.D. (1969b): Carbonate sedimentation on four southwestern Caribbean atolls and its relation to the ‘oolite problem’.—Trans. Gulf Coast Assoc. geol. Socs.19, 195–206, 14 figs., 7 tables, Miami, publications pertinent to the archipelago

Milliman, J.D. &Supko, P.R. (1968): On the geology of San Andres Island, western Caribbean Sea.—Geologie en Mijnbouw47/12, 102–105, 4 figs., s’Gravenhage. publications pertinent to the archipelago

Mitchell, R.C. (1955): Geologic and petrographic notes on the Colombian islands of La Providencia and San Andrés, West Indies.—Geologie en Mijnbouw (Nw. Ser.)17, 76–83, 3 figs., s’Gravenhage, publications referring directly to Providencia

Mora-A., H. (1940): Archipiélago de San Andrés y Providencia. —Bol. Soc. geogr. Colombia6/4, 237–249, Bogotá, publications referring directly to Providencia

Newton, A.P. (1914): The colonizing activities of the English Puritans. The last phase of the Elizabethan struggle with Spain. —XI+344 p., 3 maps., Yale Historical Publications Miscellany I, New Haven, publications referring directly to Providencia

Ogden, J. & Wicklund, R. (eds.) (1988): Mass bleaching of coral reefs in the Caribbean: a research strategy.—National Undersea Res. Program Res. Rept.88-2, 51 pp., Washington

Ortega-Ricaurte, D. (1944): Los cayos colombianos del Caribe. —Bol. Soc. geogr. Colombia7/3, 279–291, 4 figs., 8 pls., Bogotá, publications pertinent to the archipelago

Pagnacco, P.F. &Radelli, L. (1962): Note on the geology of the Isles of Providencia and Santa Catalina (Caribbean Sea, Colombia).—Geol. colombiana3, 125–132, 1 fig., Bogotá, publications referring directly to Providencia

Parsons, J.J. (1956): San Andrés and Providencia. English-speaking islands in the western Caribbean.—Publ. Geogr. (Univ. California)12/1, 1–84, 5 pls., 3 maps, 2 tables, Berkeley, publications referring directly to Providencia

Parsons, J.J. (1964): San Andrés y Providencia. Una geografía histórica de las islas colombianas del Mar Caribe occidental.— 152 p., 2 maps, Publ. Banco de la República, Bogotá

Pfaff, R. (1969):Las Scleractinia y Milleporina de las Islas del Rosario.—Mitt. Inst. colombo-alemán Invest. cient.3, 17–24, 2 figs., 1 table, Sta. Marta

Pilsbry, H.A. (1931): Results of the Pinchot South Sea Expedition. I. Land mollusks of the Caribbean islands Grand Cayman, Swan, Old Providence and St. Andrew.—Proc. Acad. nat. Sci. Philadelphia82, 221–261, 11 figs., 5 pls., Philadelphia. publications referring directly to Providencia

Porter, J.W. (1972): Ecology and species diversity of coral reefs on opposite sides of the Isthmus of Panamá.—Bull. biol. Soc. Washington2, 89–115, 13 figs., Washington

Prahl, H. von (1983): Notas sobre las formaciones de manglares y arrecifes coralinos en la Isla de Providencia, Colombia.—In: Mem. Seminario ‘Desarrollo y Planificación ambiental en las Islas de San Andrés y Providencia’ (p. 57–67, 4 figs.).—FIPMA & Ministerio de Agricultura, Bogotá, publications referring directly to Providencia

Prahl, H. von &Erhardt, H. (1985): Colombia: corales y arrecifes coralinos.—294 p., colour pls. A-N, 166 figs., FEN COLOMBIA (Fondo para la Protección del Medio Ambiente ‘José Celestino Mutis’) Bogotá, publications referring directly to Providencia

Prahl, H. von &Manjarrés, G. (1983): Cangrejos Gécarcinidos (Crustacea: Gecarcinidae) de la Isla de Providencia, Colombia. —Caribb. J. Sci.19/1–2 31–34, 2 figs., Mayagüez, publications referring directly to Providencia

Richards, H.G. (1966): Dates of some Pleistocene coral reefs in the West Indies.—Program and Abstracts, Geol. Soc. Amer., Southeastern Section, Athens, Georgia:39, p. 373, publications pertinent to the archipelago

Ripper, A. von (1949): In the West Indies with the Catherwood-Chaplin Academy Expedition.—Frontiers,13, 74–75, Philadelphia, (Acad. nat. Sci. Phila.), publications referring directly to Providencia

Rosen, B.R. (1975):The distribution of reef corals.—Rep. Underwater Ass.,1 (N.S.), 1–16, 5 figs., 1 table, London

Rowland, D. (1935): Spanish occupation of the island of Old Providence, or Santa Catalina, 1641–1670.—The Hispanic American Historical Review15, 297–312, Baltimore, publications referring directly to Providencia

Rutz-Rivas, G. (1948): El archipiélago lejano. San Andrés y Providencia.—140 p., 31 figs., 3 maps, Barranquilla (Ediciones Arte), publications referring directly to Providencia

Rützler, K. &Macintyre, I.G. (1982): The habitat distribution and community structure of the barrier reef complex at Carrie Bow Cay, Belize.—In:Rützler, K. &Macintyre, I.G. (eds.): The Atlantic barrier reef ecosystem at Carrie Bow Cay, Belize. I. Structure and communities.—pp. 9–45, figs. 1–31, Washington, (Smithsonian Institution).

Rützler, K., Santavy, D.L. &Antonius, A. (1983): The Black Band Disease of Atlantic reef corals. III. Distribution, ecology, and development.—Marine Ecology4/4, 329–358, 15 figs., 3 tables, Berlin

Sarmiento-Alarcón, A. &Sandoval, J. (1953): Comisión geológica del Archipiélago de San Andrés y Providencia. Estudio de fosfatos.—Bol. geol.1/11–12, 27–42, 6 figs., Bogotá, publications referring directly to Providencia

Schmitt, W.L. (1939): Decapod and other Crustacea collected on the Presidential Cruise of 1938 (with introduction and station data).—Smithsonian miscellan. Coll.98/6, 1–29, 3 pls., Washington publications referring directly to Providencia

Schmitt, W.L. &Schultz, L.P. (1940): List of fishes taken on the Presidential Cruise of 1938.—Smithsonian miscellan. Coll.98/25, 1–10, Washington, publications referring directly to Providencia

Schnetter, R. (1976, 1978): Marine Algen der karibischen Küsten von Kolumbien.—Bibliothecaphycologica (ed.J. Cramer)24, part I. Phaeophyceae (1976), (pp.1–126, 14 pls.);42, part II. Chlorophyceae (1978), (pp.1–200, 25 pls.), Vaduz, publications referring directly to Providencia

Schnetter, R. (1980): Algas marinas nuevas para los litorales colombianos del Mar Caribe.—Caribb. J. Sci.,15/3–4, 121–125, Mayagüez, publications referring directly to Providencia

Shackleton, N.J. &Mathews, R.K. (1977): Oxygen isotope stratigraphy of Late Pleistocene coral terraces in Barbados.— Nature268, 618–620, 1 fig., 1 table, London

Spencer, T. (1985): Weathering rates on a Caribbean reef limestone: results and implications.—Marine Geol.69, 195–201, 2 tables, Amsterdam

Stanley, D.J. &Swift, D.J.P. (1968): Bermuda’s reef front platform: bathymetry and significance.—Marine Geol.6/6, 479–500, 8 figs., Amsterdam

Taylor, W.R. (1939): Algae collected on the Presidential Cruise of 1938.—Smithsonian miscellan. Coll.98/9, 1–18, 14 figs., 2 pls., Washington, publications referring directly to Providencia

Tyler, J.C. &Böhlke, J.E. (1972): Records of sponge-dwelling fishes primarily of the Caribbean.—Bull. marine Sci.22/3, 601–642, 2 figs., Coral Gables, publications referring directly to Providencia

Valderrama, R. & Pérez, G. (1978): The geology of San Andrés and Providencia Islands.—In: Collection Eighteenth annual Field Conference, Colombia.—Soc. Petroleum Geol. and Geophys. Colombia, p. 499–545, 6 figs., 11 pls., Bogotá, publications referring directly to Providencia

Vanderbilt, G. (1944): Results of the Fifth George Vanderbilt Expedition (1941): Introduction and itinerary.—Acad.nat. Sci. Philadelphia, Monogr.6, 1–6, Philadelphia, publications referring directly to Providencia

Wadge, G. &Wooden, J.L. (1982): Late Cenozoic alkaline volcanism in the northwestern Caribbean: tectonic setting and Sr isotopic characteristics.—Earth and planet. Sci. Lett.57, 35–46, 4 figs., 2 tables, Amsterdam, publications referring directly to Providencia

Wells, J.W. (1973): New and old scleractinian corals from Jamaica. —Bull. marine Sci.23/1, 16–58, 36 figs., 1 append., Miami

Wells, S. (1988) (ed.): Coral reefs of the world. Vol. 1: Atlantic and Eastern Pacific, UNEP Regional Seas Directories and Bibliographies, xlvii + 373 pp., 38 maps., IUCN, Gland (Switzerland) and Cambridge, U.K./UNEP, Nairobi, publications referring directly to Providencia

Werding, B. (1984): Porcelánidos (Crustacea: Anomura: Porcellanidae) de la Isla de Providencia, Colombia.—An. Inst. Invest. marinas Punta de Betín14, 3–16, 3 figs., Sta.Marta, publications referring directly to Providencia

Williams, E.H., Jr. &Bunkley-Williams, L. (1990): The world-wide coral reef bleaching cycle and related sources of coral mortality.—Atoll Res. Bull.335, 1–71, 4 figs., 23 tables, 1 appendix, Washington

Wilson, P.J. (1973): Crab antics. The social anthropology of English-speaking negro societies of the Caribbean.—Caribbean Ser.14, 1–258, 8 figs., 5 tables, New Haven, (Yale University Press), publications referring directly to Providencia

Woodley, J.D., Chornesky, E.A., Clifford, P.A., Jackson, J.B.C., Kaufman, L.S., Knowlton, N., Lang, J.C., Pearson, M.P., Porter, J.W., Rooney, M.C., Rylaarsdam, K.W., Tunnicliffe, V.J., Wahle, C.M., Wulff J.L., Curtis, A.S.G., Dallmeyer, M.D., Jupp, B.P., Koehl, M.A.R., Neigel, J., Sides, E.M. (1981): Hurricane Allen’s impact on Jamaican coral reefs.— Science214 (Nr. 4522), 749–755, 4 figs., 2 tables, New York

Zea, S. (1987): Esponjas del Caribe colombiano.—286 p., 84 figs., 11 tables, 14 pls., Catálogo Cientifico, Bogotá, publications referring directly to Providencia

Zea, S. &Soest, R.W.M. van (1986): Three new species of sponges from the Colombian Caribbean.—Bull. marine Sci.38/2, 355–365, 4 figs., Miami, publications referring directly to Providencia

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Geister, J. Modern reef development and cenozoic evolution of an oceanic island/reef complex: Isla de Providencia (Western Caribbean sea, Colombia). Facies 27, 1–69 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02536804

Received:

Revised:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02536804