By Rachel Kang

Gender-affirming care is defined by the World Health Organization as the implementation of any social, psychological, behavioral, or medical interventions designed to support and affirm a person’s gender identity. This form of care is essential for the mental well-being of transgender folks who experience gender dysphoria, which can appear in children as young as 7 years old1. In celebration of Pride Month, let’s discuss what gender-affirming care really is, and why it should be easier for people to receive this care.

What is gender dysphoria?

Gender dysphoria is defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR) as a “marked incongruence between a person’s experienced or expressed gender and the one they were assigned at birth.” In other words, gender dysphoria occurs when a person’s body and sex characteristics do not align with their psychological sense of their gender. This misalignment can cause a sense of unease or dissatisfaction that can lead to depression and anxiety. Gender-affirming care is one method of addressing gender dysphoria in helping trans folks feel more at ease with their bodies.

What is gender-affirming care?

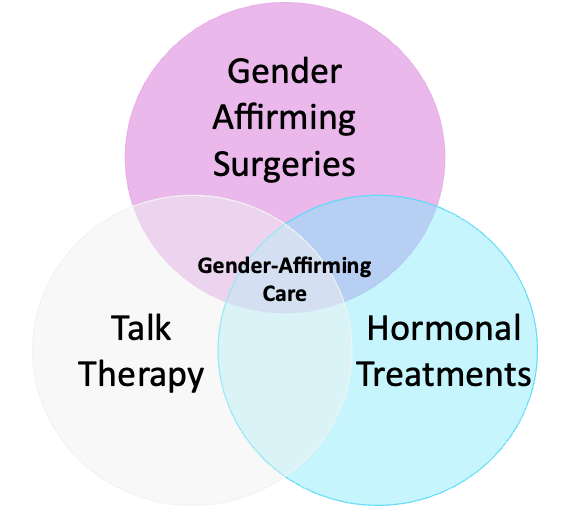

Many forms of gender-affirming care exist for people wanting to address their gender dysphoria (Figure 1). Some people may elect to undergo gender-affirming surgical procedures, like top surgery, to have their physical bodies match their gender identity. Others may take hormonal treatments with estrogen or testosterone to change their bodies more subtly to match their gender identity, such as with voice changes or hair growth. Trans folks can also attend therapy to cognitively address their gender dysphoria.

Gender-affirming Surgeries

Gender affirmation surgery is one of the most utilized forms of gender-affirming care and is used to help a trans person transition their body into exhibiting the characteristics associated with their correct gender. The most common procedure is top surgery that either enlarges, reduces, or removes beast tissue from a person’s chest2. Other forms of gender-affirming surgery can include facial surgery to change a person’s face shape or bottom surgery which involves the removal or creation of genitalia to fit a person’s gender expression.

Though surgery may seem drastic to some, one study found that less than 1% of patients who underwent gender-affirming surgery expressed any form of post-surgery regret3. In contrast, a study examining patient surgical regret, predominately in cancer patients, reported that 1 in 7 patients experience some kind of decisional regret as a result of their surgical procedure.4 Interestingly, another study reported that 47.2% of women who underwent breast reconstruction following a mastectomy for breast cancer treatment experienced some level of post-surgery regret5. The study reported that the regret stemmed from patients having a negative body image post-surgery because these their bodies no longer resembled how they thought they should look – a perspective which strongly resembles gender dysphoria experienced by trans folks.

Hormonal Treatments

Other trans people may choose to undergo hormonal treatment to change their body’s physiology. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT), first used to combat menopausal symptoms in older women using estrogen injections, has been used in gender-affirming care since the 1960s, with the method reaching a peak in popularity in the 1990s6. Now, many trans people utilize HRT to stop their bodies from producing their native hormone, replacing it with the hormone that better fits their gender identity. For instance, feminizing hormone therapy involves the use of an androgen blocker to stop production of testosterone, and then additionally taking estrogen to replace the native hormones.

Before undergoing HRT, some trans teens may decide to use puberty blockers to delay or stop puberty-related changes in the body. A drug known as gonadotropin releasing hormone agonist suppresses the production of sex hormones and have been prescribed to adolescents since the mid-1990s7. Puberty blockers are completely reversible, and choosing to take them offers the teen time to explore their identity before physiological characteristics develop that may cause gender dysphoria. The decision also gives trans children time to speak with a physician and further explore what forms of gender-affirming care would be right for them8,9.

Talk Therapy

Gender-affirming talk therapy focuses on affirming a patient’s gender identity rather than trying to “fix” the individual. 40% of transgender youth are reported to mostly or always feel depressed, compared to only 14% of non-LGBTQ youth10. Talk therapy can be used to reduce the negative effect of societal stigmas against trans individuals and improve their mental health.

While many forms of gender-affirming care exist, some trans individuals may choose to not undergo any kind of care at all. Suffering is not a necessary component of the trans experience. Trans folks are trans no matter what they choose to do with their body and how they choose to express their gender.

What are the steps involved with receiving Gender-affirming care?

One of the biggest worries regarding trans health is the idea that trans identities are just fads, and children will one day regret transitioning so early in life. This is not the case: a study found that the majority of trans people (86.9%) who have transitioned are happy with their decision. Of the comparatively small percentage that have de-transitioned, 82.5% of them cited an external factor, like societal or familial pressures, that influenced their decision to de-transition11. Despite this finding, a growing population of people worry that the transitioning process is too easy. In recent news, some states have passed laws banning gender-affirming care for minors altogether, ostensibly to prevent minors from making “irresponsible” choices (Florida, West Virginia, Ohio, General Map of Bans).

So, how easy is it to obtain gender-affirming care?

Many trans individuals will undergo hormonal treatments prior to surgery. Historically, a teen has needed a referral letter from a mental health professional before receiving treatment, to confirm that the patient was suffering from gender dysphoria and had the capacity to provide informed consent. However, more and more medical facilities are expanding their HRT access by only requiring an informed consent form to be signed, removing all other prerequisites. Hormone therapy is still only provided to individuals over 18 years old; however, 16–17-year-old adolescents can receive hormones with parental consent12.

To be eligible for gender affirmation surgery, the individual must be at least 18 years old, and have the following13:

- A letter from a medical professional stating the patient does have persistent and well documented gender dysphoria with specifics on length of hormonal therapy.

- A letter from a therapist stating the patient has gender dysphoria, all other significant mental health concerns are well controlled, and that the patient has been living full-time in their identified gender for at least 12 months.

- A second letter from a mental health professional that states that the patient is ready for surgery with full understanding of the surgical procedure, recovery, fertility implications, and risks of surgery.

While many insurances do cover gender-affirming care, a gender dysphoria diagnosis is required to be submitted for such coverage to be awarded. Without insurance, HRT can range from $20 – $80 a month, and surgeries can range from $5,000 to $50,000. Although it is illegal for insurance companies to discriminate against transgender individuals, insurances can still refuse to cover transition-related care14. One study found that 25% of trans people surveyed were denied coverage for HRT, and 55% of trans people surveyed were denied gender-affirming surgeries.15 Denials can occur for a variety of reasons, such as not meeting the physical or mental health requirements mentioned above, or insurance companies taking the position that the gender-affirming care is cosmetic and not a medical necessity.

Gender-affirming care is not a cosmetic surgery that a person would undergo just for aesthetic reasons. It is a life-altering procedure that validates and affirms a person’s identity. The goal of gender-affirming care isn’t to make someone look like someone else: it is to help a person feel at home in their own bodies. While every trans person’s transition journey may look different, there is no doubt that gender-affirming care is essential, and anyone who might need it should have access to it.

TL:DR

- Gender-affirming care encompasses therapy, hormonal treatment, and surgical procedures to help combat gender dysphoria.

- The goal of gender-affirming care is to help trans folks feel at home in their bodies.

- It’s pride month! Go out and support your LGBTQ+ friends. 😊

References

1. Zaliznyak M, Bresee C, Garcia MM. Age at First Experience of Gender Dysphoria Among Transgender Adults Seeking Gender-Affirming Surgery. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(3):e201236. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.1236

2. Lane M, Ives GC, Sluiter EC, et al. Trends in Gender-affirming Surgery in Insured Patients in the United States. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2018;6(4):e1738. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000001738

3. Bustos VP, Bustos SS, Mascaro A, et al. Regret after Gender-affirmation Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Prevalence. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2021;9(3):e3477. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000003477

4. Wilson A, Ronnekleiv-Kelly SM, Pawlik TM. Regret in Surgical Decision Making: A Systematic Review of Patient and Physician Perspectives. World J Surg. 2017;41(6):1454-1465. doi:10.1007/s00268-017-3895-9

5. Sheehan J, Sherman KA, Lam T, Boyages J. Association of information satisfaction, psychological distress and monitoring coping style with post-decision regret following breast reconstruction. Psycho-Oncology. 2007;16(4):342-351. doi:10.1002/pon.1067

6. Cagnacci A, Venier M. The Controversial History of Hormone Replacement Therapy. Medicina (Kaunas). 2019;55(9):602. doi:10.3390/medicina55090602

7. Giordano S, Holm S. Is puberty delaying treatment ‘experimental treatment’? Int J Transgend Health. 2020;21(2):113-121. doi:10.1080/26895269.2020.1747768

8. Panagiotakopoulos L. Transgender medicine – puberty suppression. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2018;19(3):221-225. doi:10.1007/s11154-018-9457-0

9. Turban JL, King D, Carswell JM, Keuroghlian AS. Pubertal Suppression for Transgender Youth and Risk of Suicidal Ideation. Pediatrics. 2020;145(2):e20191725. doi:10.1542/peds.2019-1725

10. Human Rights Campaign Foundation. Post-Election Survey of Youth. Published online 2017. http://assets.hrc.org//files/assets/resources/HRC_PostElectionSurveyofYouth.pdf

11. Turban JL, Loo SS, Almazan AN, Keuroghlian AS. Factors Leading to “Detransition” Among Transgender and Gender Diverse People in the United States: A Mixed-Methods Analysis. LGBT Health. 2021;8(4):273-280. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2020.0437

12. Nitkin K. Helping Transgender Children and Youth. Published November 28, 2018. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/news/articles/helping-transgender-children-and-youth

13. Boston Children’s Hospital. Eligibility for Surgery. Accessed April 14, 2023. https://www.childrenshospital.org/programs/center-gender-surgery-program/eligibility-surgery

14. Bakko M, Kattari SK. Transgender-Related Insurance Denials as Barriers to Transgender Healthcare: Differences in Experience by Insurance Type. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(6):1693-1700. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-05724-2

15. James S, Herman J, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, Anafi. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. Published online December 2016.