Louis Armstrong (1901-1971) and Bing Crosby (1903-1977) are two of the most well-known performers of the twentieth century. Born three years apart in states at opposite ends of the country, the two left their childhood homes in New Orleans and Spokane in the 1920s to pursue a music career in Chicago and Los Angeles. The pair met as young adults at the Sunset Café in Chicago in 1926. Crosby heard Armstrong perform there and found his stage presence and musical abilities impressive. Scholar Gary Giddins describes Crosby’s reaction to Armstrong’s performance as follows:

Crosby apparently could not believe his eyes or his ears, because what really knocked him out was that Armstrong would do one number that would practically bring you to tears, and then the very next number he’d put on his deacon’s coat and do an impersonation of a Deep South preacher and have everybody bowled over in the aisles.[1]

In a 1950 letter written by Armstrong, he remembers a time he witnessed Crosby in action. His words commend the entertainer.

…The next time I dug my boy Bing’-was at the Paramount Theatre in New York. He had been there for weeks – when, one day’ I came into the APPLE (New York) and, there before mine eyes, Bing Crosby. Headlining the show that mees. The minute I sat my bags down at home I made a Bee line, over to the Paramount and Ol’ Bing Crosby AS WE “CATS UP IN HARLEM’ called him in those days- Ofcourse nowadays, I call’s him Pappa Bing. The show I caught at the Paramount, was a thrill as well as a surprise to me. He had matured wonderfully- and above all, a very fine comedian. My my that man Bing delivered, a couple of lines while singing to a chick, -made me laugh so hard and so loud, until my stomach was hurting and I had to hold it – my tummy. The whole house just roared…[2]

Armstrong and Crosby continued to cross paths and became friends while working on various films, radio and television shows, and making an album entitled Bing and Satchmo (1960).

Armstrong and Crosby were some of the early users of new entertainment technologies. In 1931 RCA introduced the bidirectional ribbon microphone. This microphone differed from previous iterations in many ways. It had “better pickup, frequency range, and dynamic range, which greatly improved sound quality.”[3] Academic Allison McCracken states that this kind of microphone increased the vocal resonance in singers’ voices, especially when they would stand close to it.[4] New microphone technology was important for crooners such as Crosby, but also for Armstrong, especially during the 1930s when he was expanding his musical identity by covering commercial popular songs.

Armstrong and Crosby standing close to a microphone while recording “Pennies from Heaven” in 1936

During their musical careers, Armstrong and Crosby had to deal with criticism from various sources. Armstrong received comments that labeled him as an “Uncle Tom” and apathetic toward racial injustice. Meanwhile, Crosby handled critiques concerning his drinking habit as well as his crooner identity. Before Crosby, many Americans identified crooners with soft, high-pitched, romantic voices as effeminate and even immoral. In the 1930s, Crosby’s team, which included his producer, Jack Kapp, and his family members, worked hard to distinguish him from previous crooners. McCracken claims that when Crosby emerged on the scene, he projected a new image and sound of white heterosexual masculinity that set the standard for other male popular singers.[5]

The professional journeys of Armstrong and Crosby differed in other ways. As a white performer, Crosby had certain advantages – he had control over his career and the ability to move upward in the entertainment industry without as many challenges as Armstrong. This is not to say that Crosby had it easy or that Armstrong did not have agency. Crosby used his pull for good when he demanded that Armstrong receive the same billing as the main stars in the film Pennies from Heaven (1936). This was a big achievement as it was the first time a Black performer received this kind of recognition in a major motion picture.

Throughout the years, some journalists and fans have questioned whether Armstrong’s and Crosby’s friendship was all for show, given that they never went over to each other’s houses. Today certain people still speculate that Crosby might have had underlying feelings of prejudice that manifested when he was out of the public eye. Armstrong’s remarks in a 1961 issue of Ebony Magazine elucidate his opinion on his and Crosby’s relationship. He states:

But we [Armstrong and Crosby] aren’t social. Even in the early days, we didn’t go cabareting together. I didn’t go out with the Hollywood colony then-and still don’t. I don’t even go out with the modern stars, even though I’ve played with a lot of them – Danny Kaye, Sinatra. I don’t even know where they live. In fact, I’ve never been invited to the home of a movie star – not even Bing’s. You don’t have to be in people’s faces to appreciate the warmth they have for you. We all appreciate each other’s talents. Do I think any of them have a lingering prejudice? If they do, they don’t show it. They must be damn good actors. I’d feel chilliness in a minute.[6]

When Crosby was queried about these issues his response was that Armstrong had never invited him over to his house either. It was also well-known that Crosby valued his privacy and seldom invited people over.

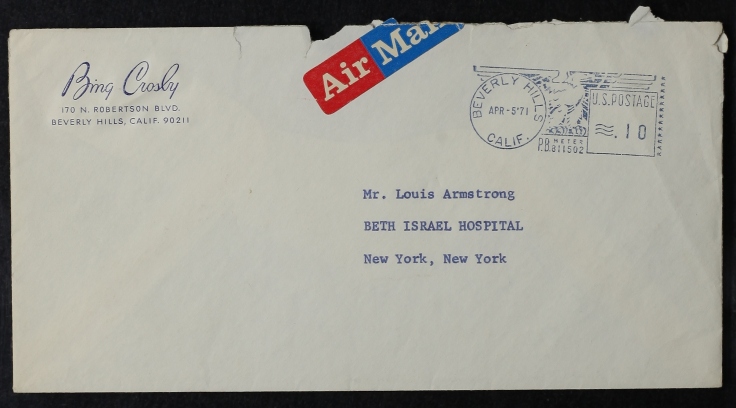

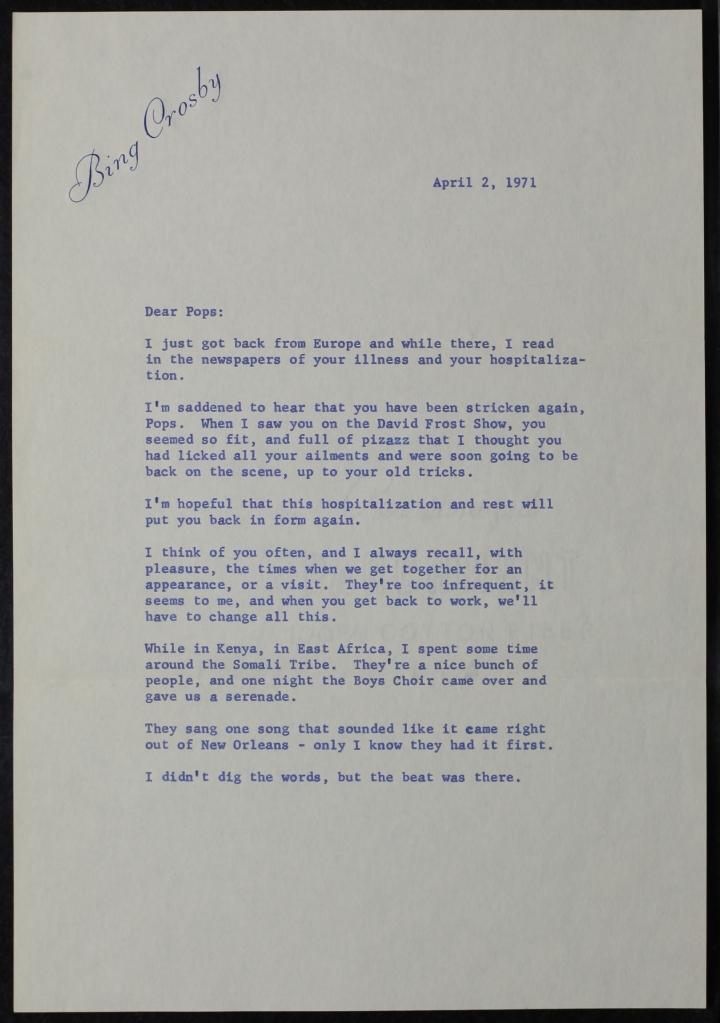

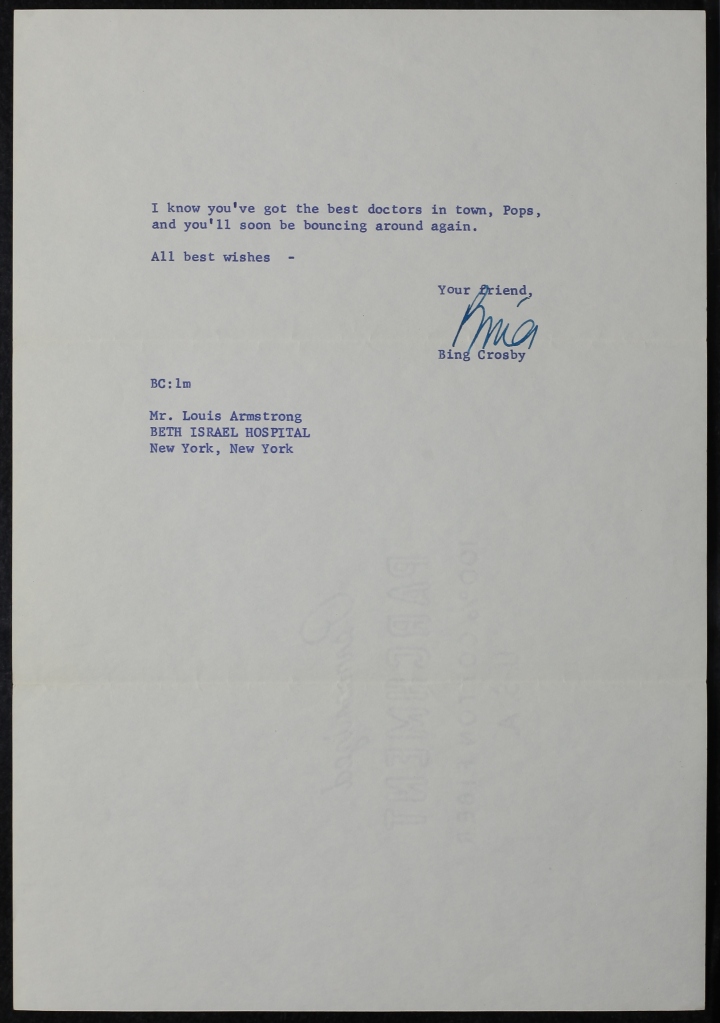

Armstrong and Crosby continued to correspond in their later years. When Armstrong was hospitalized in Beth Israel Hospital in New York in 1971, he received a letter from Crosby that spoke of their friendship, recalled old memories, and offered well wishes (see below). At Armstrong’s funeral, Crosby was one of the honorary pallbearers.

Armstrong’s and Crosby’s mutual admiration and respect for one another increased when they worked together professionally. Both were diligent and determined performers who possessed charisma and a sense of humor. During different decades in American history, their captivating voices served as a vehicle for expressing American blackness and whiteness. They created new singing practices, utilized new technologies to their advantage, and reinvented what it meant to be an entertainer. Together and apart they helped transform the American music industry.

[1] “Bing and Louis: A Pocketful of Dream with Gary Giddins,” The Jim Cullum Riverwalk Jazz Collection, accessed October 30, 2020, https://riverwalkjazz.stanford.edu/?q=program/bing-and-louis-pocketful-dreams-gary-giddins.

[2] “Letter to Unknown,” Object ID1987.9.9, January 1, 1950, https://collections.louisarmstronghouse.org/asset-detail/1008123, The Louis Armstrong Archives.

[3] Allison McCracken, Real Men Don’t Sing: Crooning in American Culture (Durham: Duke University Press, 2015), 288.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid, 19.

[6] “Daddy, How the Country Has Changed!” Ebony Magazine, Object ID: 2005.3.491, May 1, 1961, https://collections.louisarmstronghouse.org/asset-detail/1097067, The Louis Armstrong Archives.