Peter Lobner, updated 25 April 2024 (Rev. 6)

1. Introduction

Modern Airships is a three-part document that contains an overview of modern airship technology in Part 1 and links in Parts 1, 2 and 3 to more than 275 individual articles on historic and advanced airship and aerostat designs. This is Part 2. Here are the links to the other two parts:

- Modern Airships – Part 1: https://lynceans.org/all-posts/modern-airships-part-1/

- Modern Airships – Part 3: https://lynceans.org/all-posts/modern-airships-part-3/

To help you navigate the large volume of material in these three documents, please refer to following indexes. The first index simply lists the article titles in alphabetic order within each Part.

Parts 1 & 2 address similar types of airships and unpowered aerostats. The following airship type index enables you to see all of the airships and aerostats addressed in Parts 1 & 2, grouped by type, with direct links to the relevant articles.

The airships described in Part 3 are relatively exotic concepts in comparison to the more utilitarian and heavy-lift airships that dominate Parts 1 and 2. As shown in the following index, the airships in Part 3 are organized by function rather than airship type, which sometimes is difficult to determine with the information available.

Modern Airships – Part 2 begins with a set of graphic tables that identify the airships addressed in this part, and concludes by providing links to more than 115 individual articles on those airships. A downloadable pdf copy of Part 2 (Rev. 6) is available here:

Each of the linked articles can be individually downloaded.

If you have any comments or wish to identify errors in these documents, please send me an e-mail to: [email protected].

I hope you’ll find the Modern Airships series to be informative, useful, and different from any other single document on this subject.

Best regards,

Peter Lobner

25 April 2024

Record of revisions to Part 2

- Original Modern Airships post, 26 August 2016: addressed 14 airships in a single post.

- Expanded the Modern Airships post and split it into three parts, 18 August 2019: Part 2 included 25 articles

- Part 2, Revision 1, 21 December 2020: Added 2 new articles on Walden Aerospace. Part 2 now had 27 articles

- Part 2, Revision 2, 3 April 2021: Added 35 new articles, split the original variable buoyancy propulsion article into three articles, and updated all of the original articles. Also updated and reformatted the summary graphic table. Part 2 now had 64 articles.

- Part 2, Revision 3, 9 September 2021: Updated 7 articles. Added category for “thermal (hot air) airships” and added pages for them in the summary graphic table. Part 2 still had 64 articles.

- Part 2, Revision 4, 11 February 2022: Added 26 new articles, expanded the graphic tables and updated 12 existing articles. A detailed summary of changes incorporated in Part 2, Rev 4 is listed here. Part 2 now had 90 articles.

- Part 2, Revision 5, 10 March 2022: Added 1 new article, split rigid & semi-rigid airships in the graphic tables, and updated 52 existing articles. With this revision, all Part 2 linked articles have been updated in February or March 2022. A detailed summary of changes incorporated in Part 2, Rev 5 is listed here. Part 2 now has 91 articles.

- Part 2, Revision 6, 17 March 2024: This revision includes a major reorganization of Parts 1 & 2 to better aggregate airships and unpowered aerostats by type, with a corresponding reorganization of the graphic tables. Over the past two years, 28 new articles were added to Part 2 and 27 articles were updated. In the final changes for Rev. 6, several articles were moved between Parts 1 & 2. A detailed summary of changes incorporated in Part 2, Rev 6 is listed here. Part 2 now has 117 articles.

Part 2, changes since Rev. 6 (17 March 2024)

New articles:

- None yet

Updated articles:

- None yet

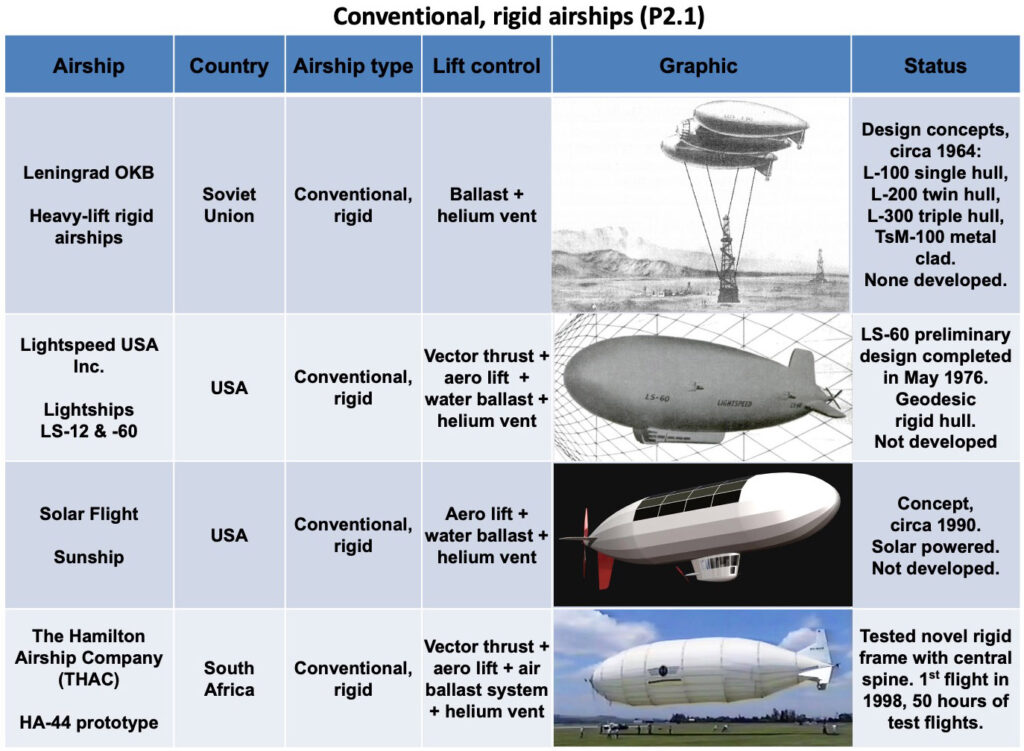

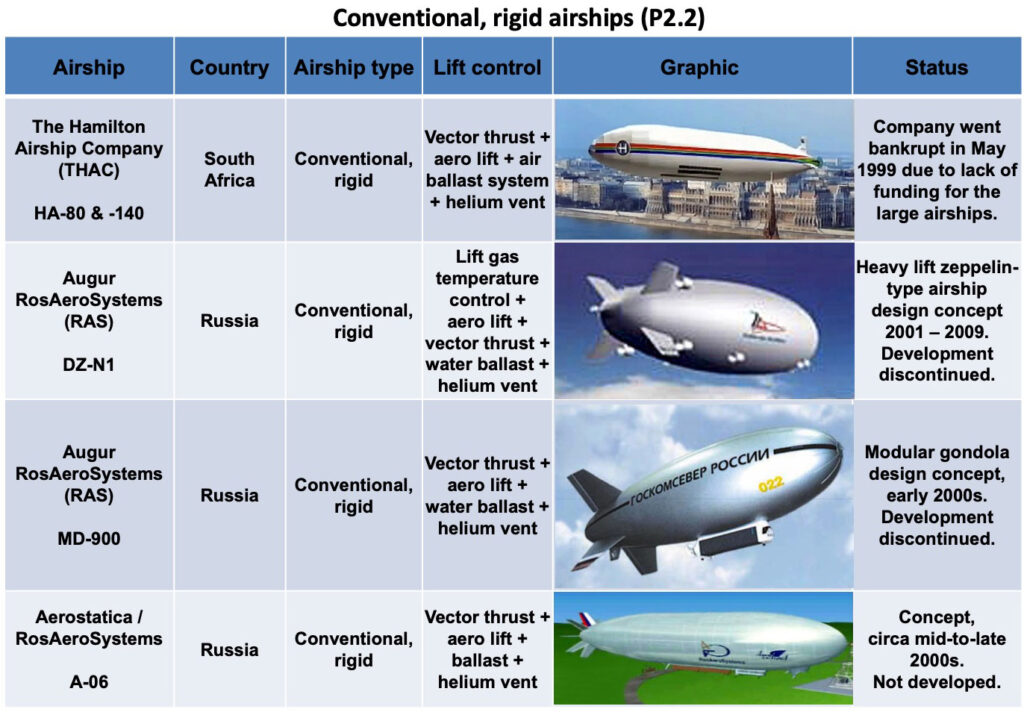

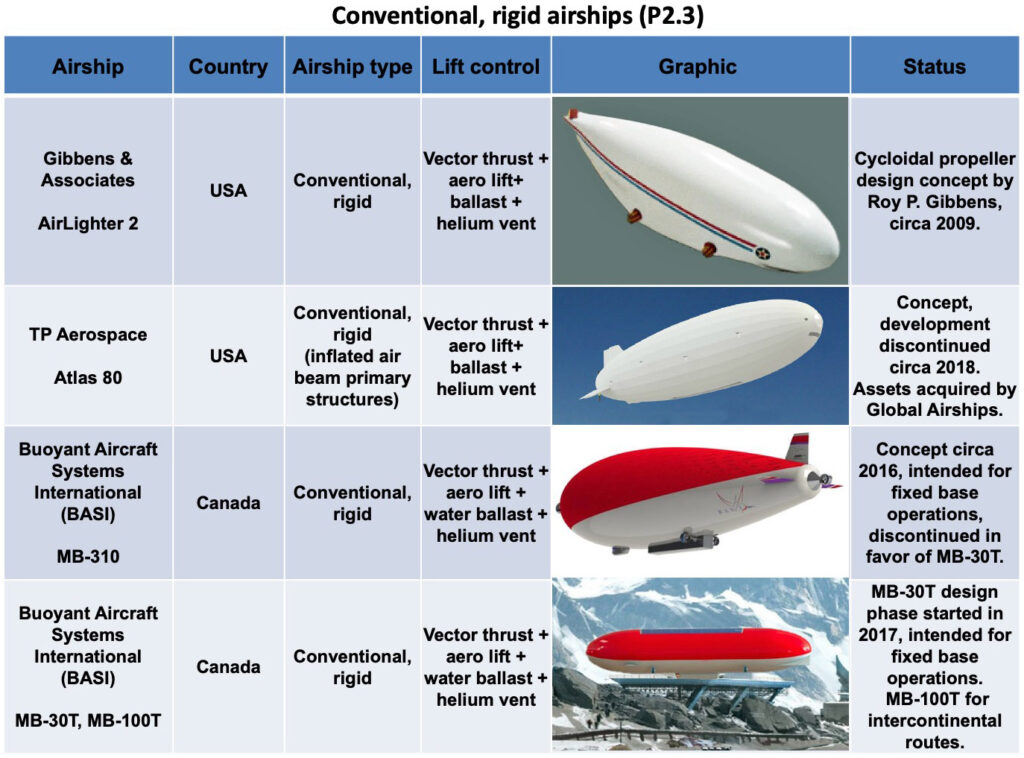

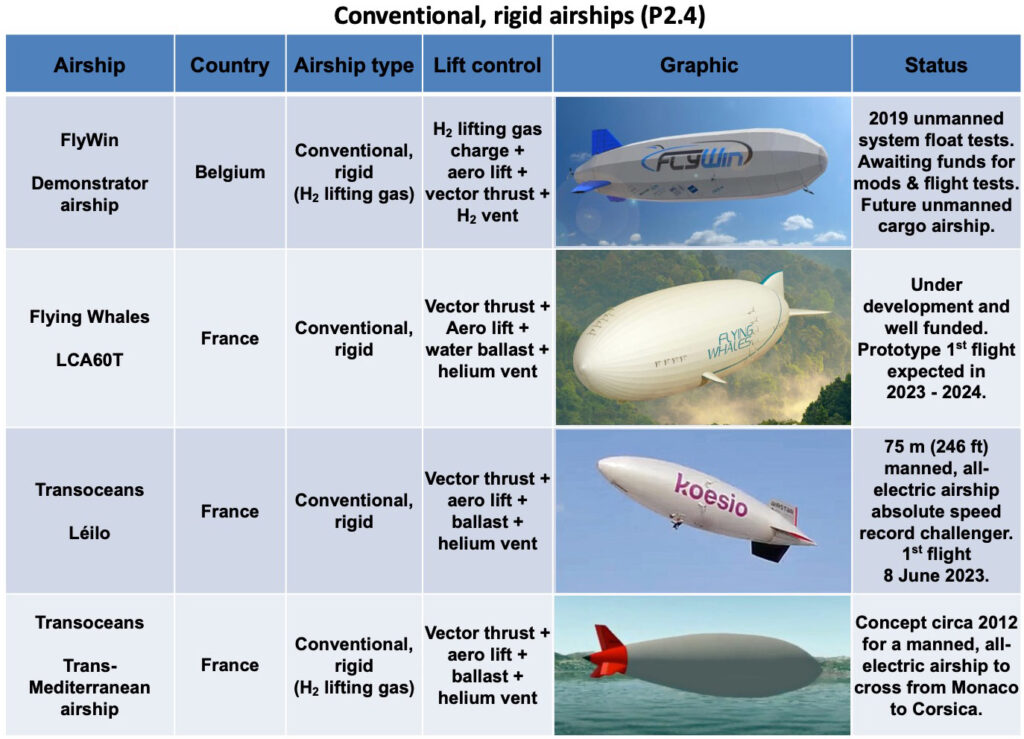

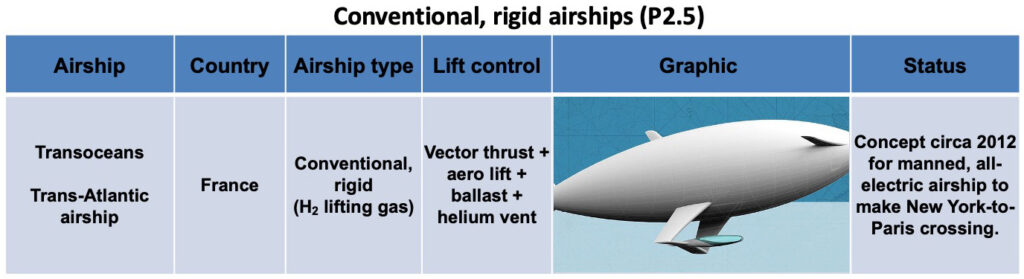

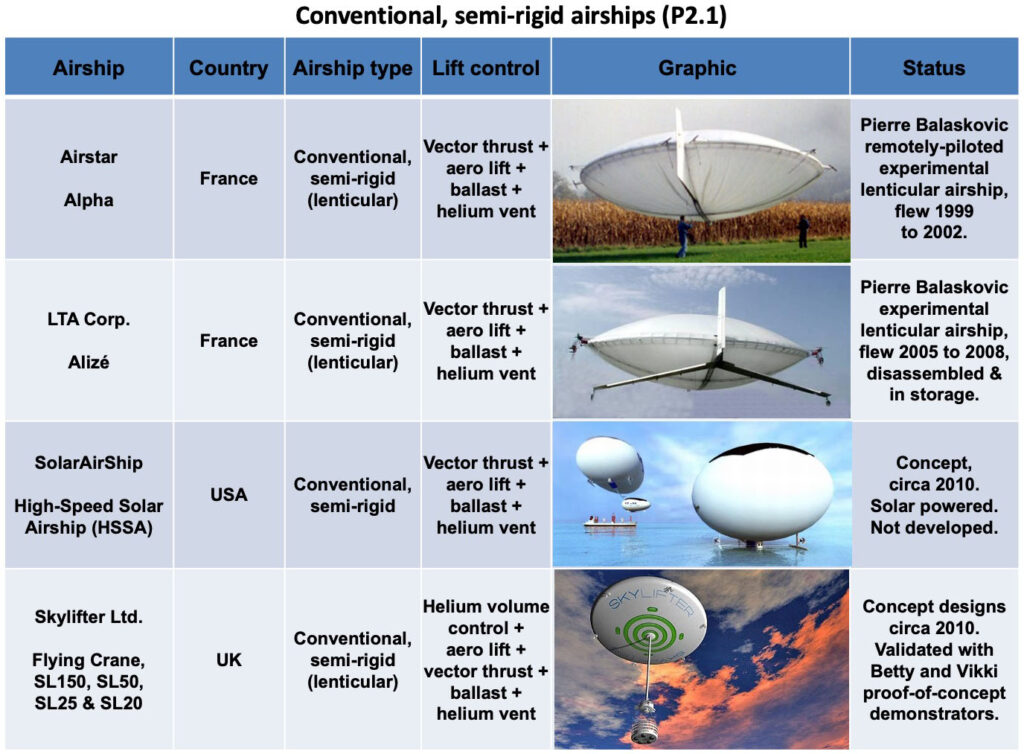

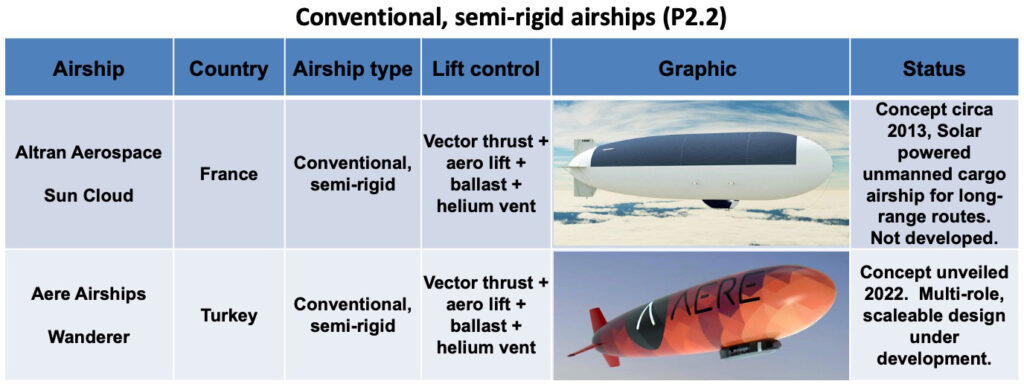

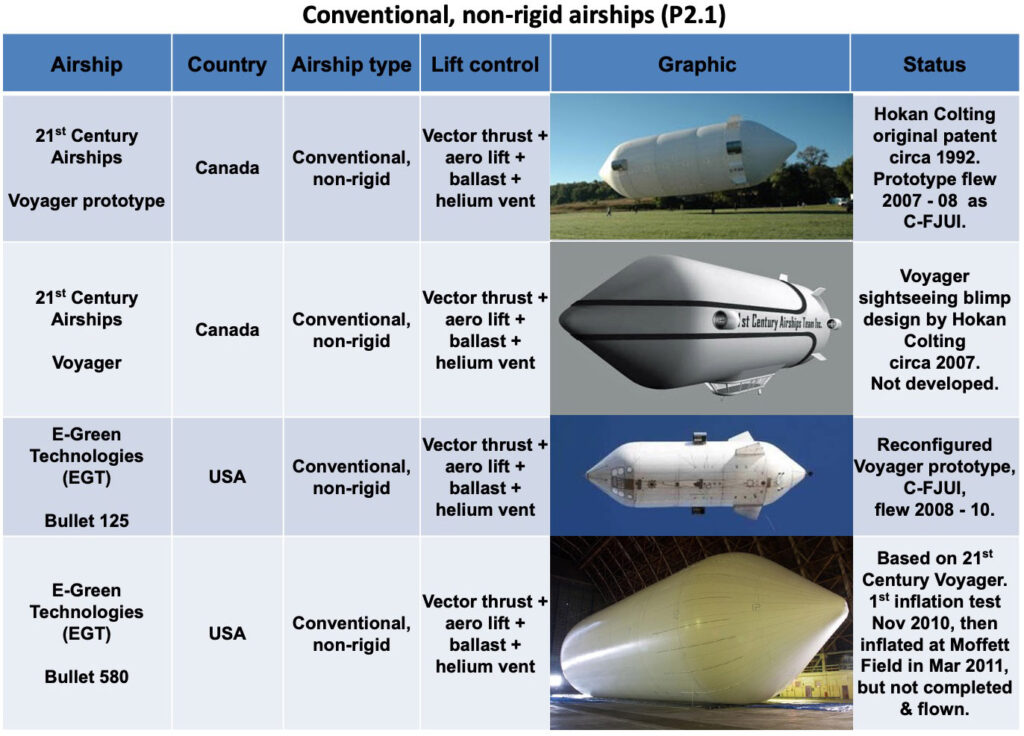

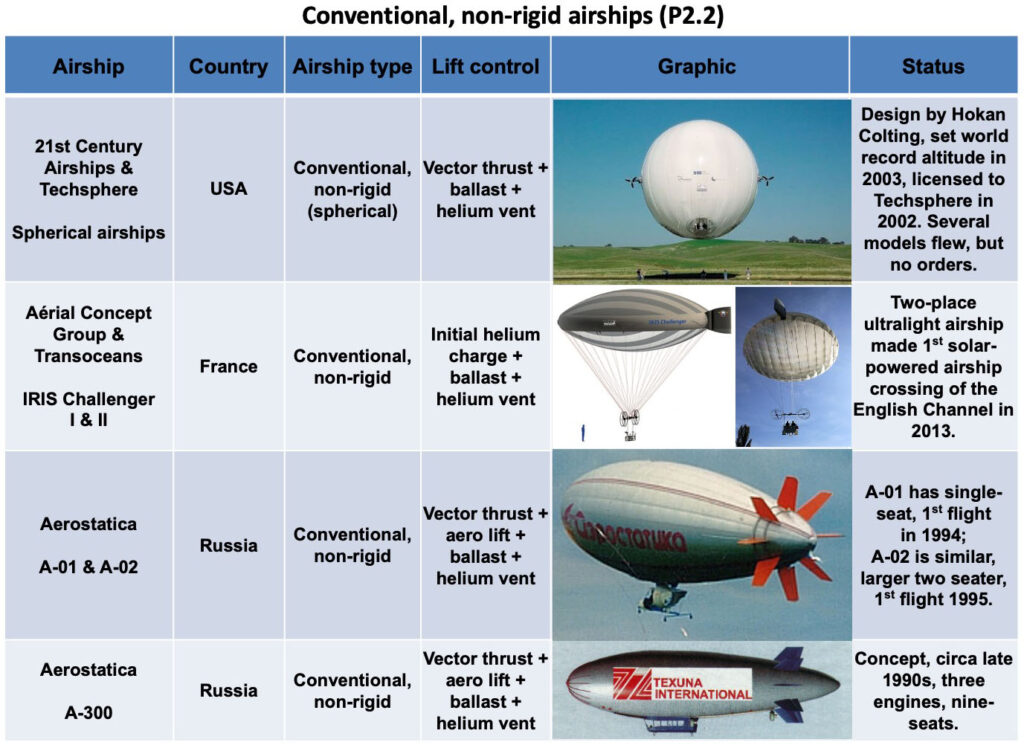

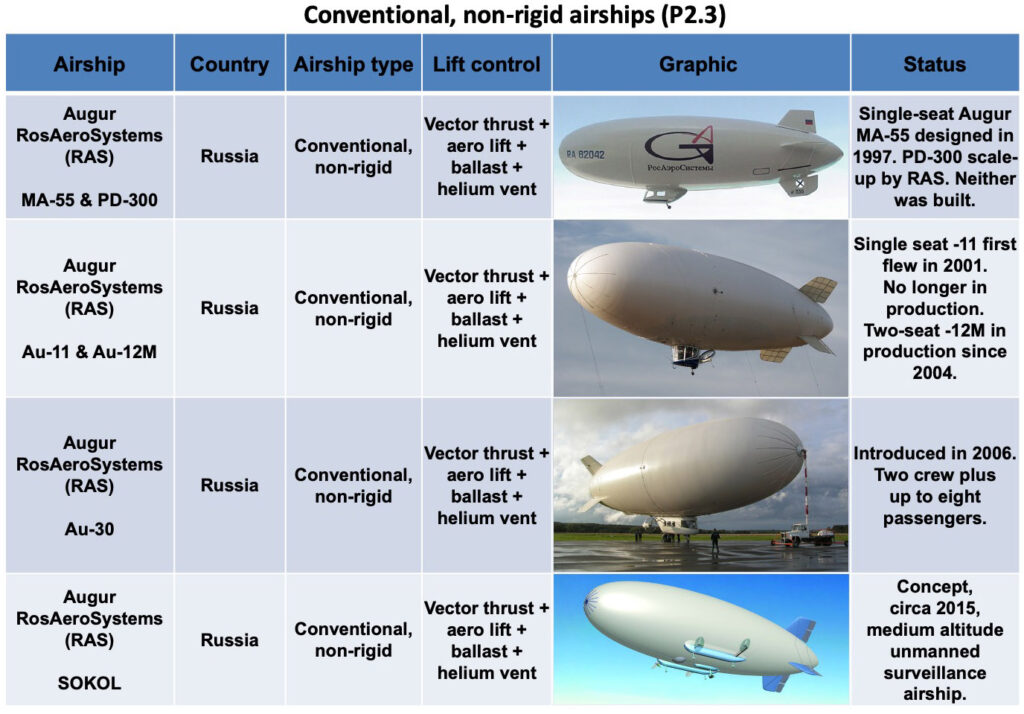

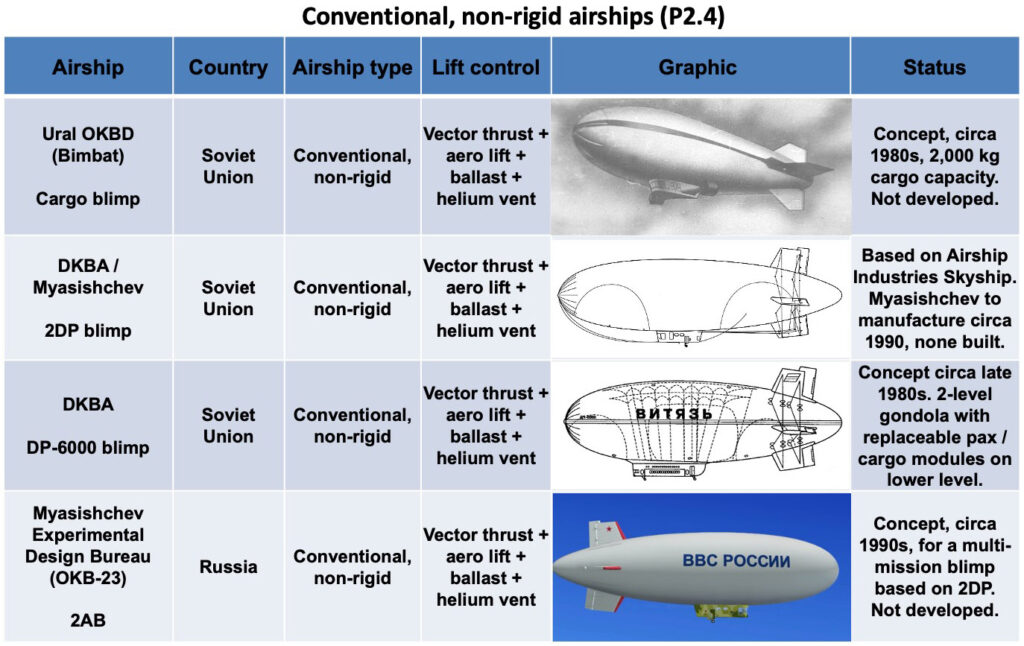

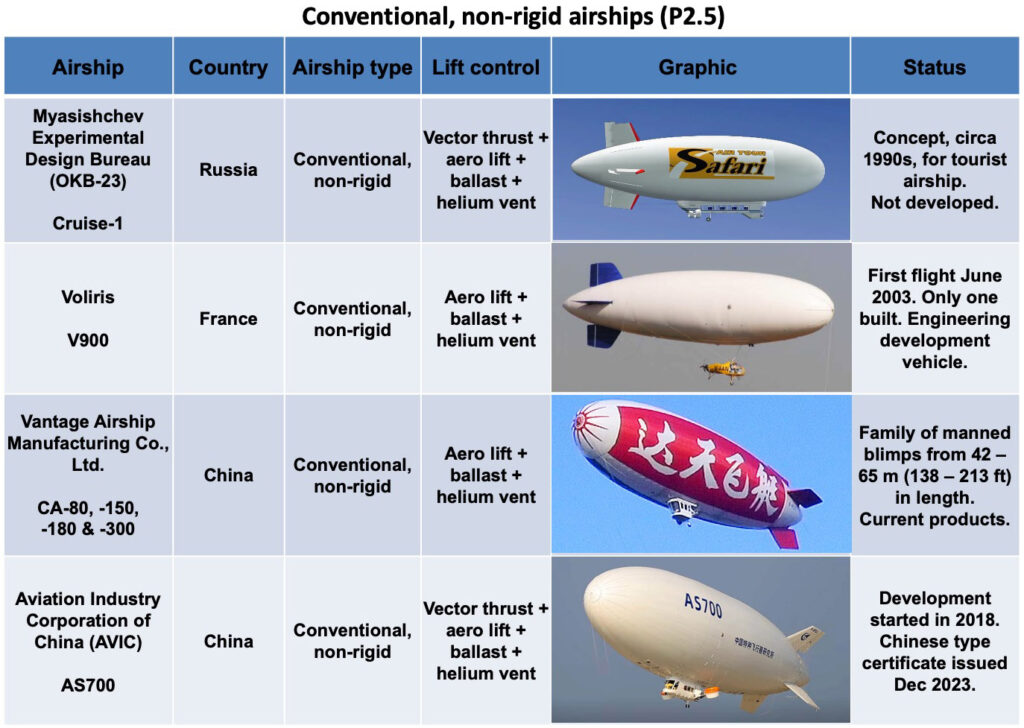

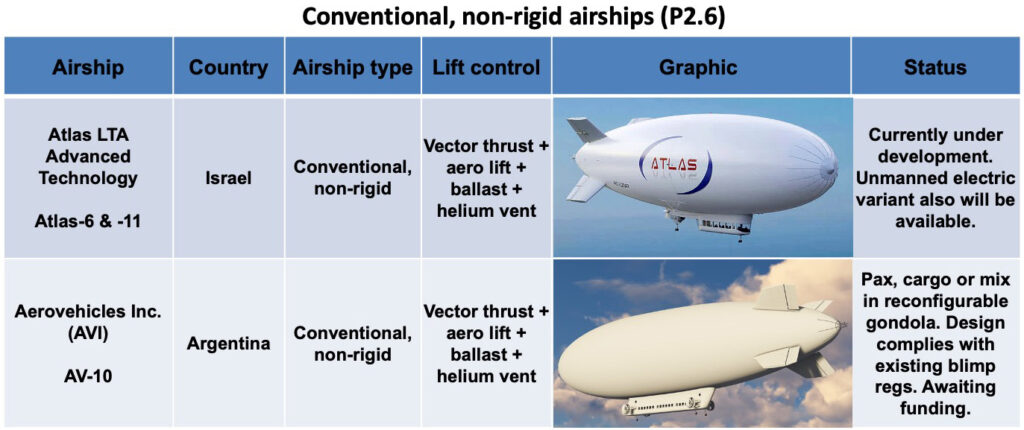

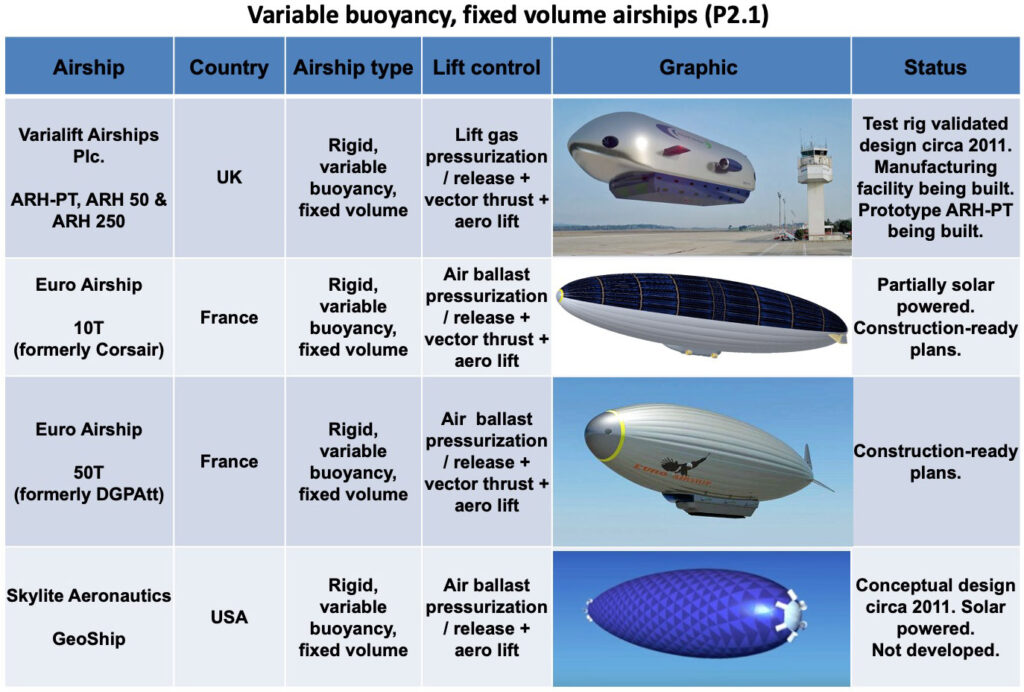

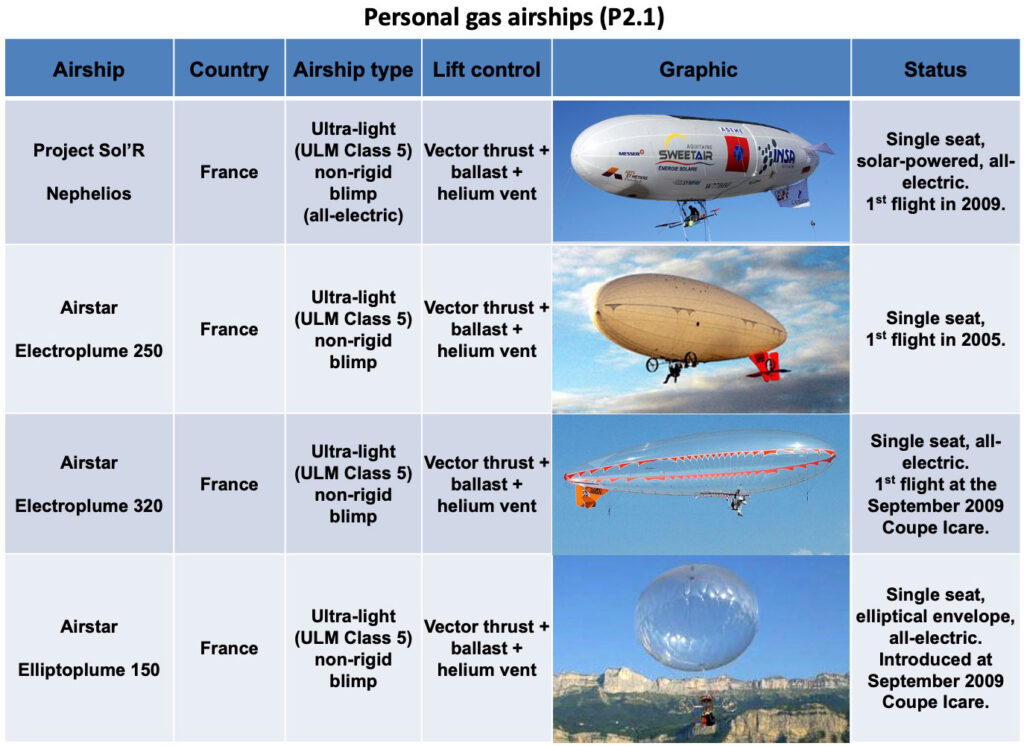

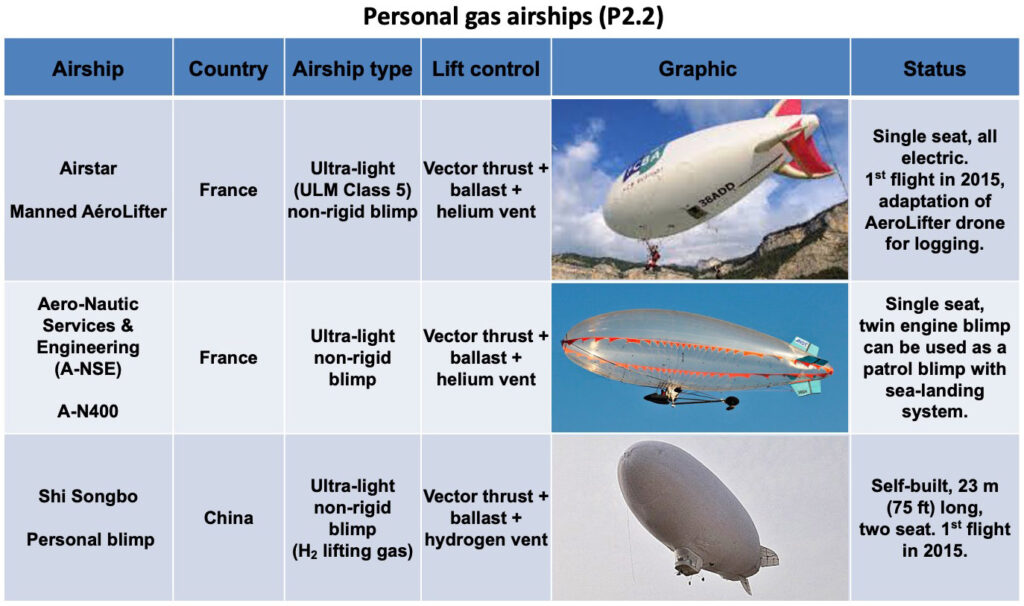

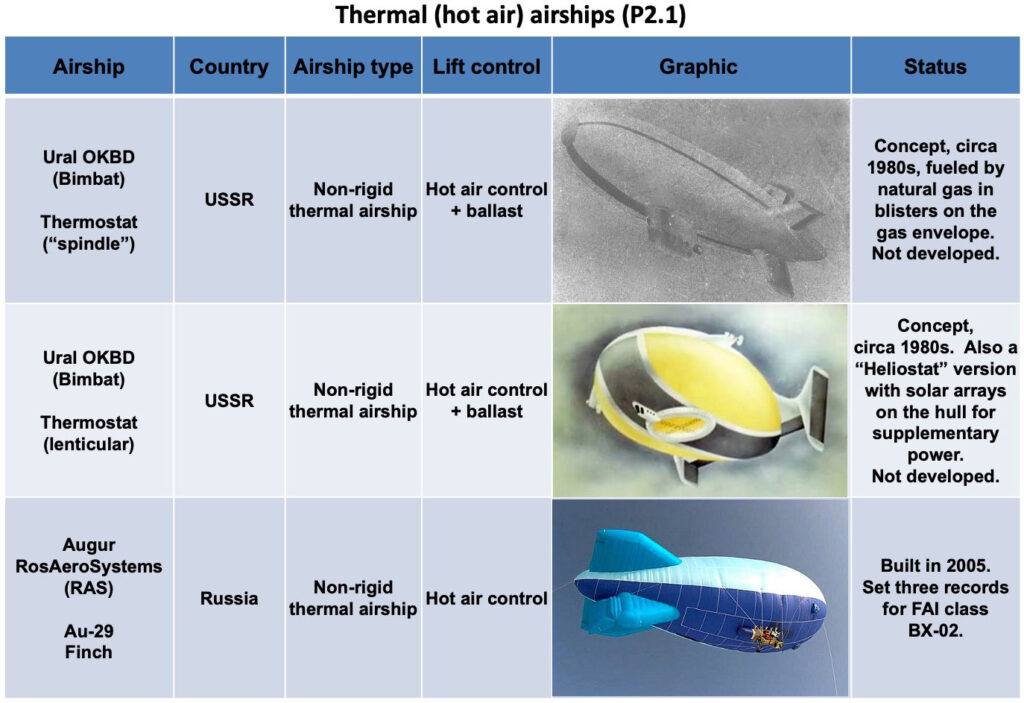

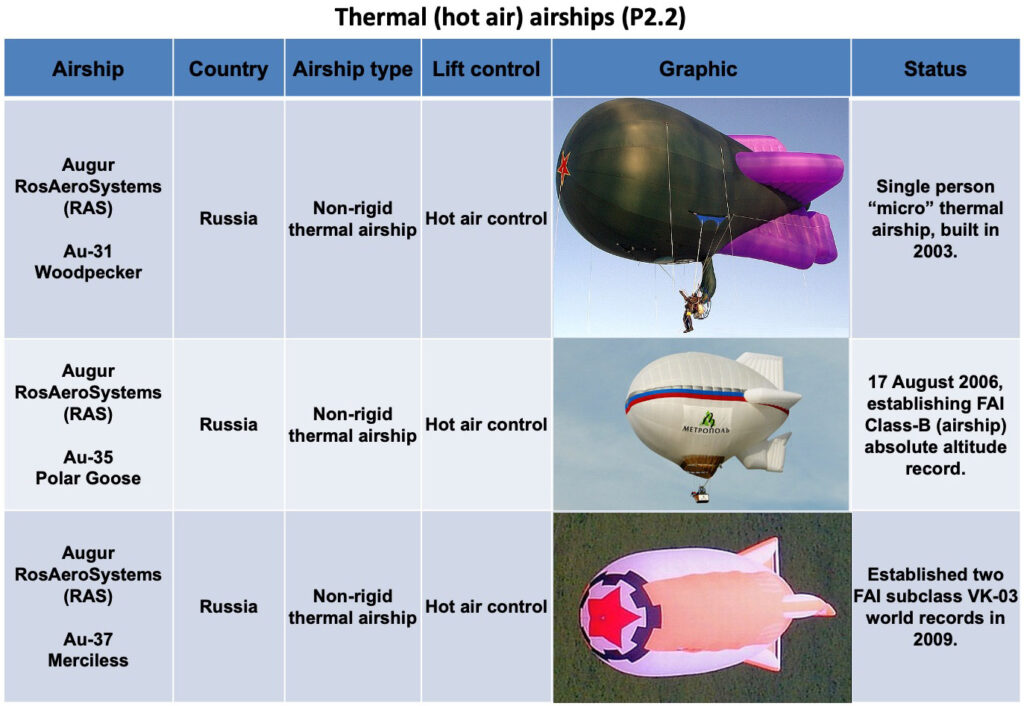

2. Graphic tables

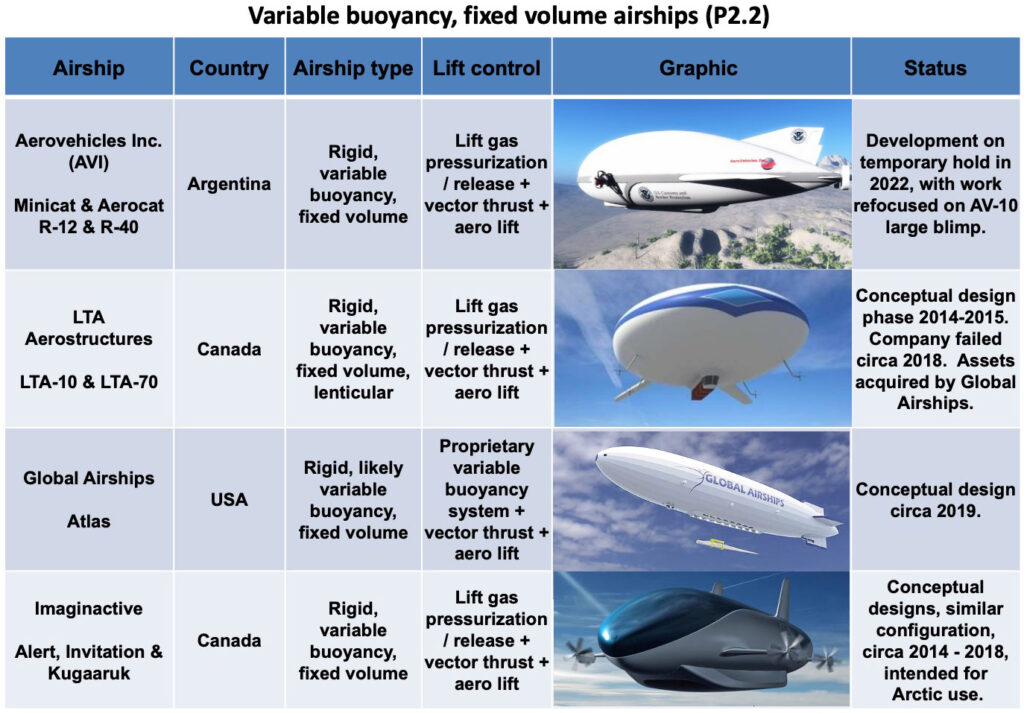

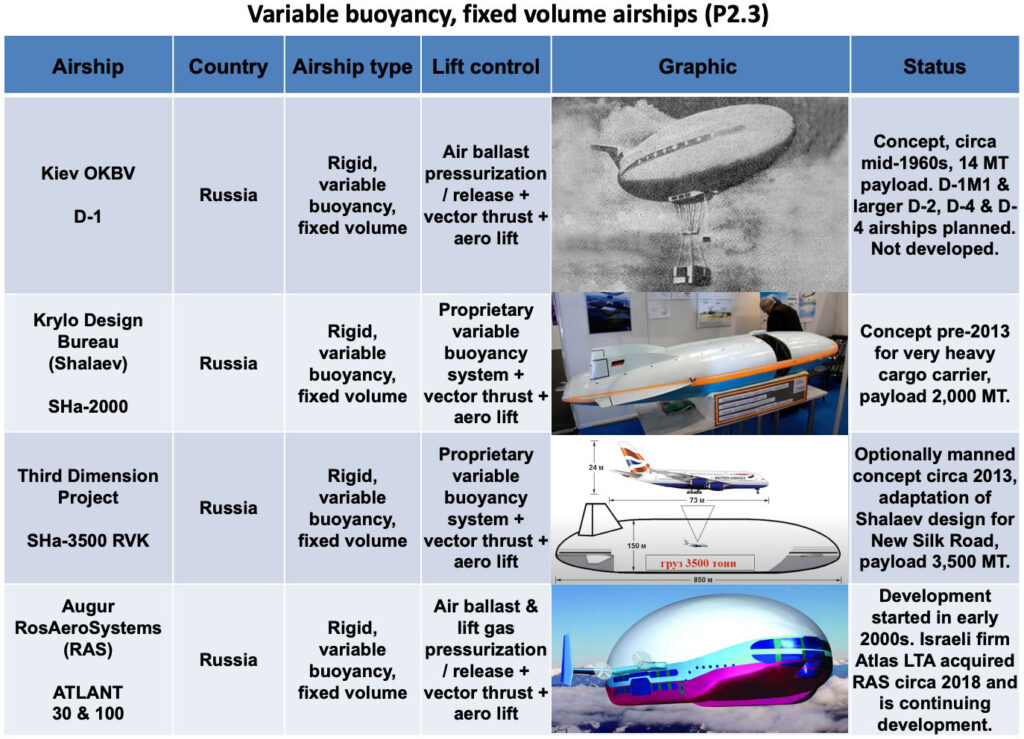

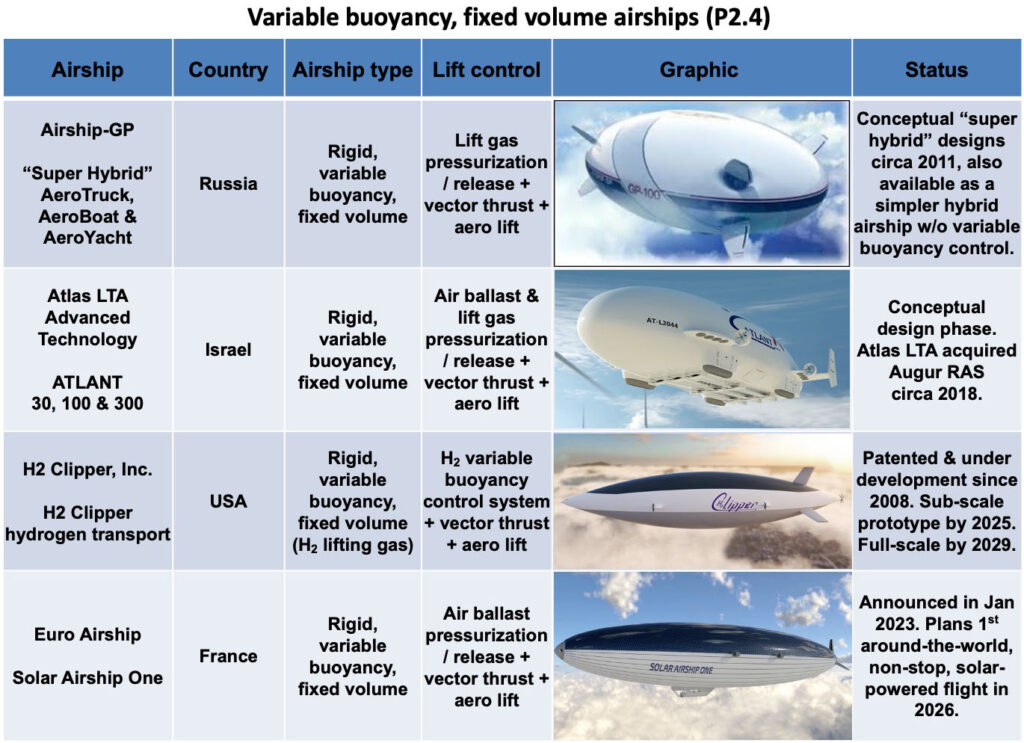

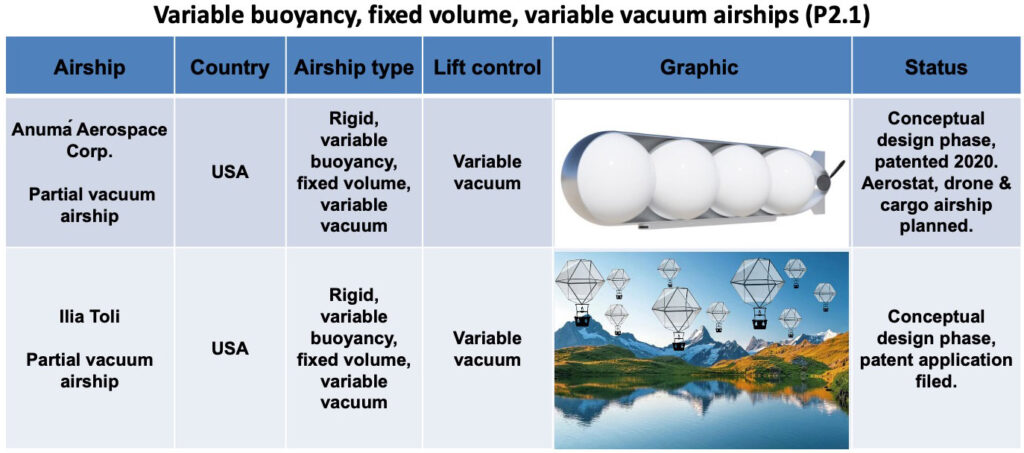

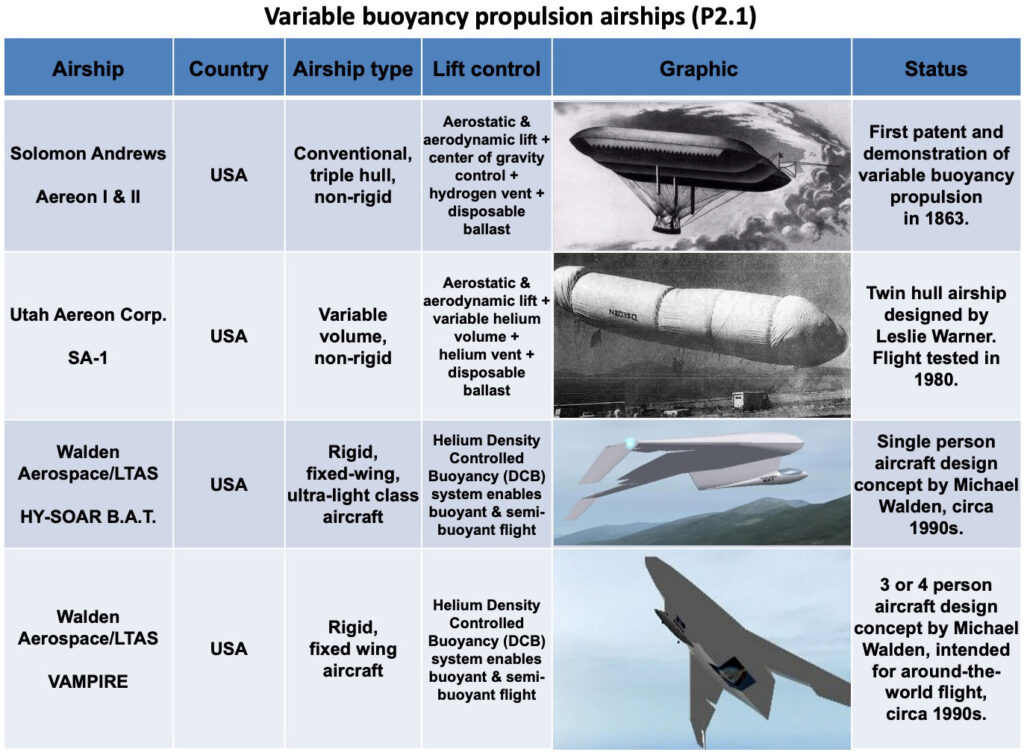

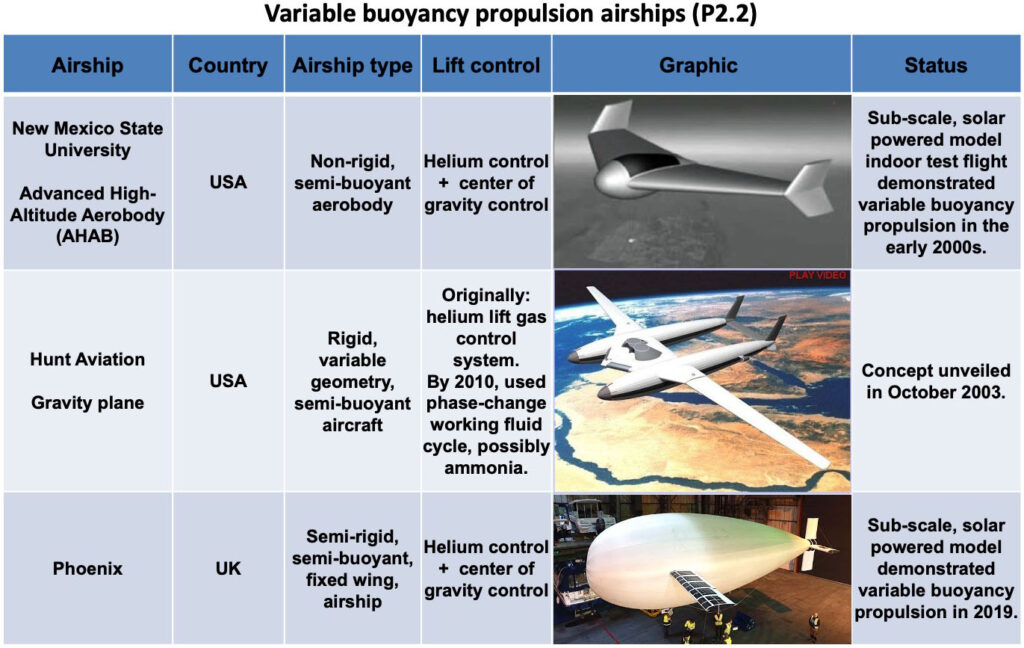

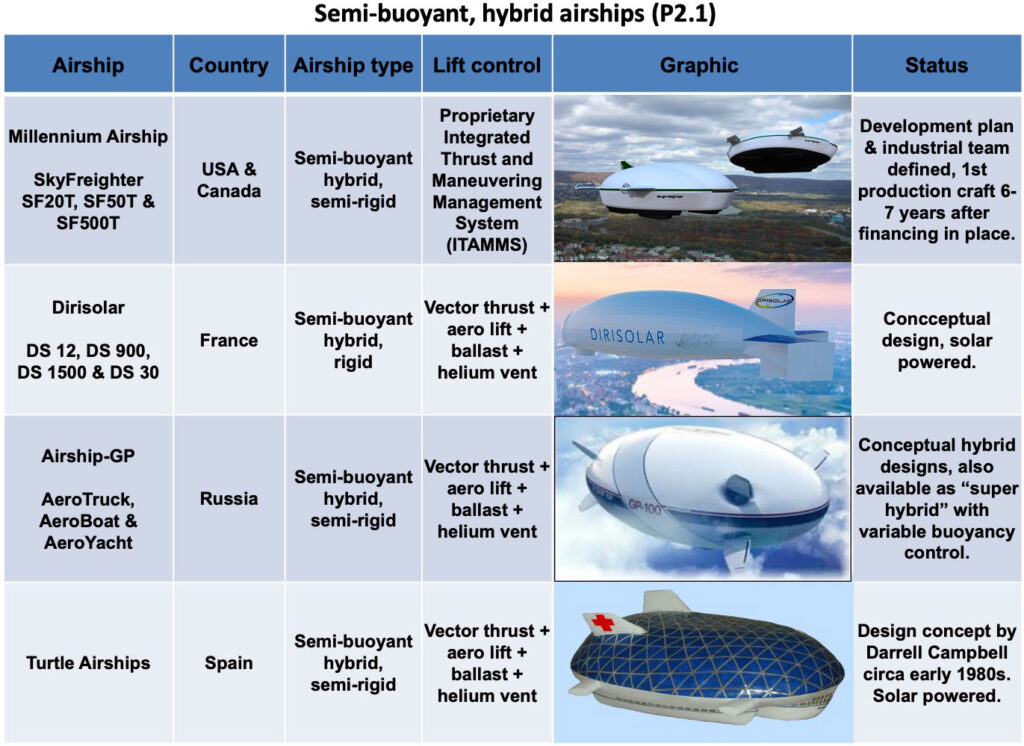

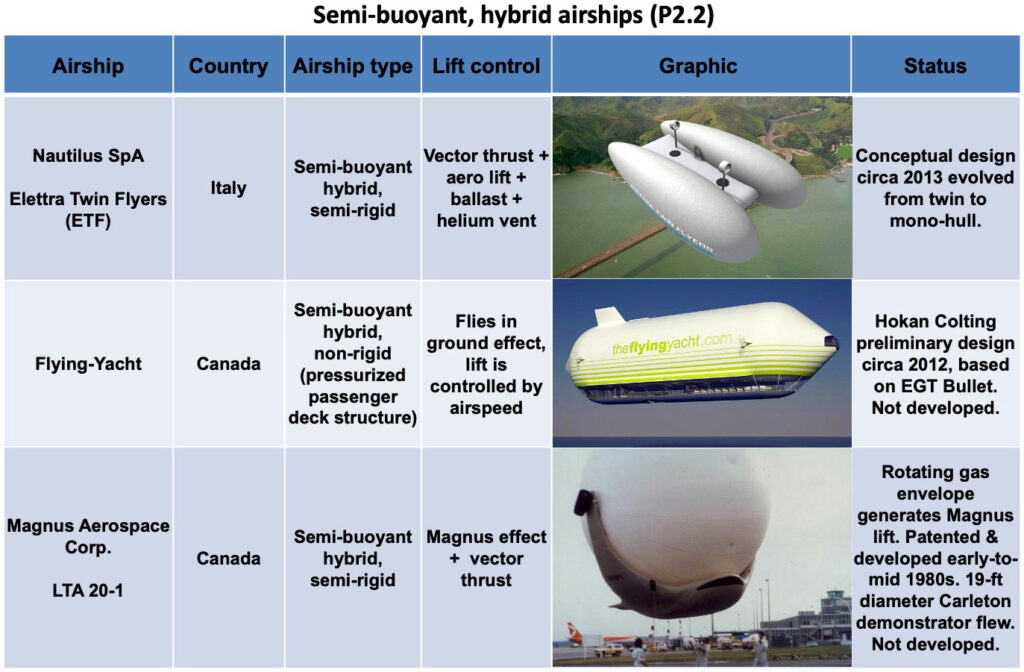

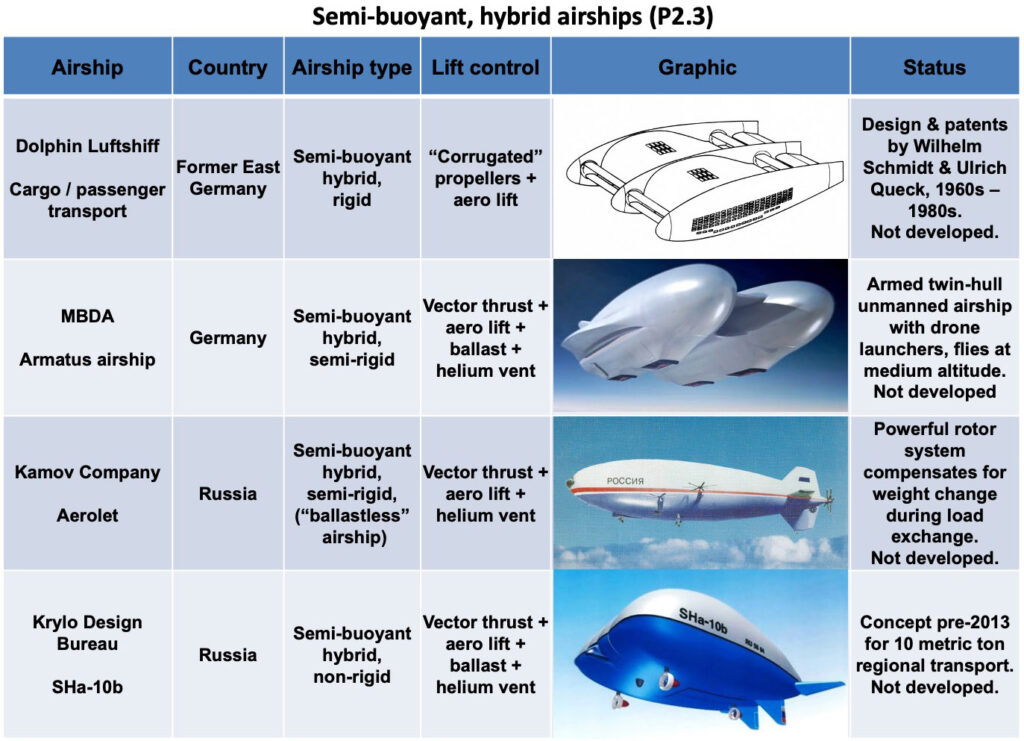

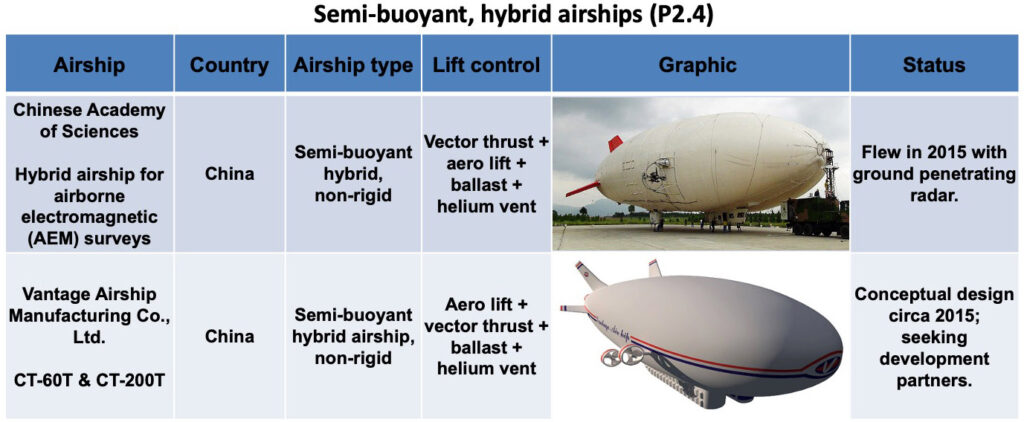

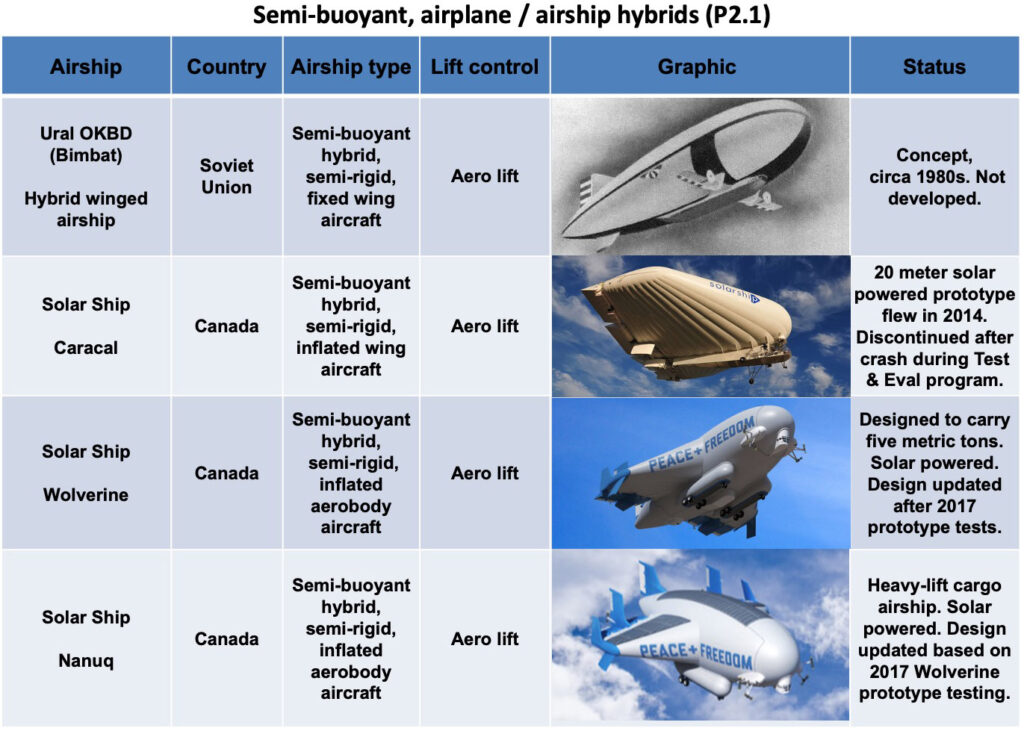

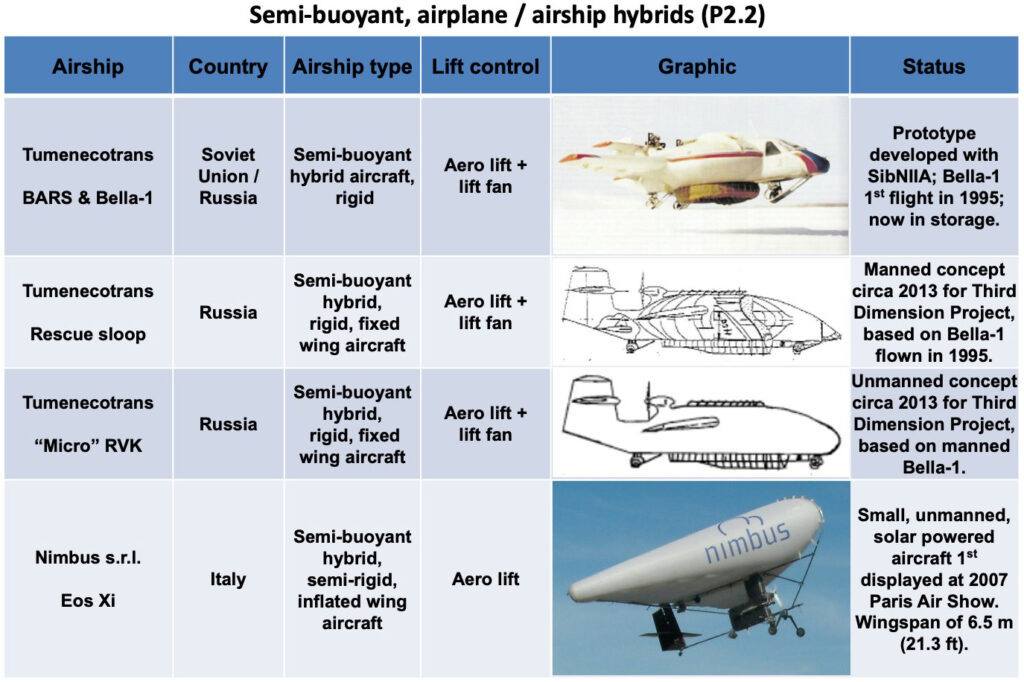

The airships reviewed in Modern Airships – Part 2 are summarized in the following set of graphic tables that are organized into the categories listed below:

- Conventional airships

- Rigid airships

- Semi-rigid airships

- Non-rigid airships (blimps)

- Variable buoyancy airships

- Variable buoyancy, fixed volume airships

- Variable buoyancy, fixed volume, variable vacuum airships

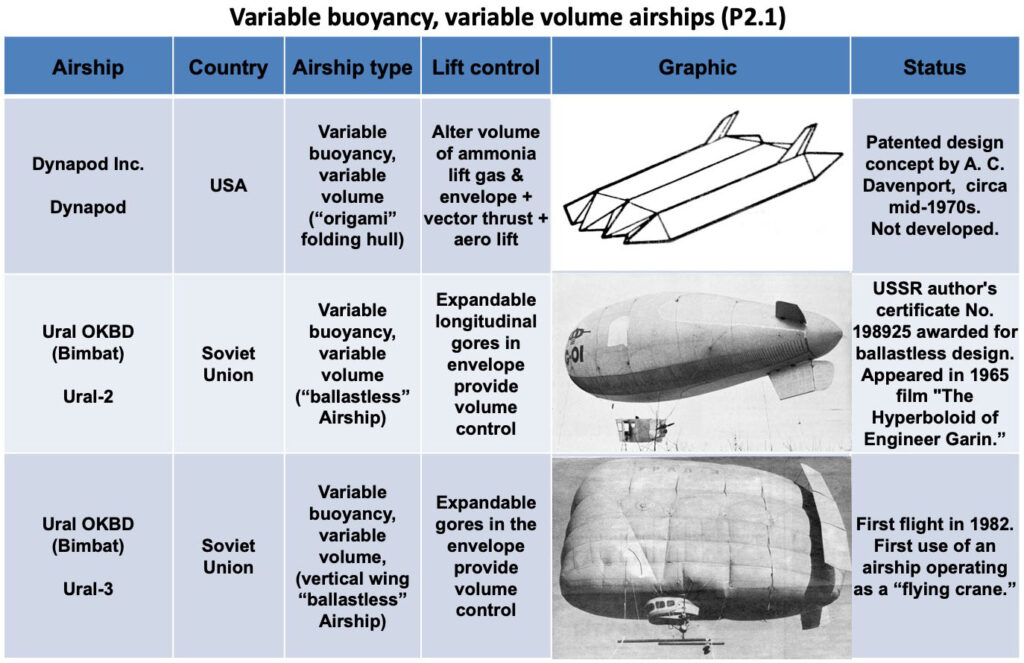

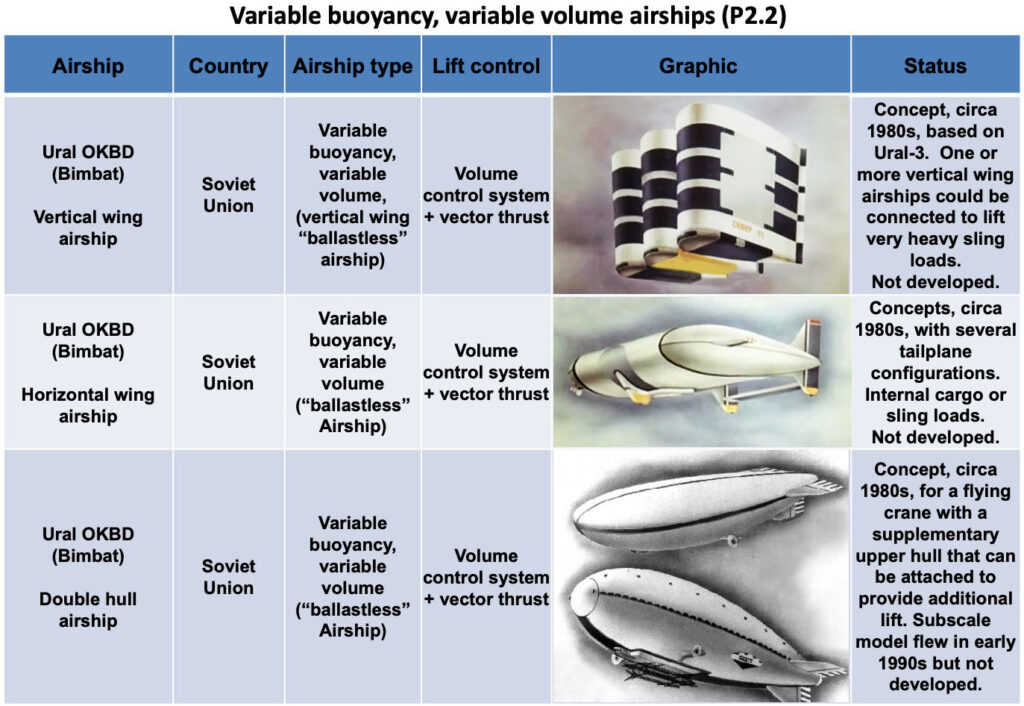

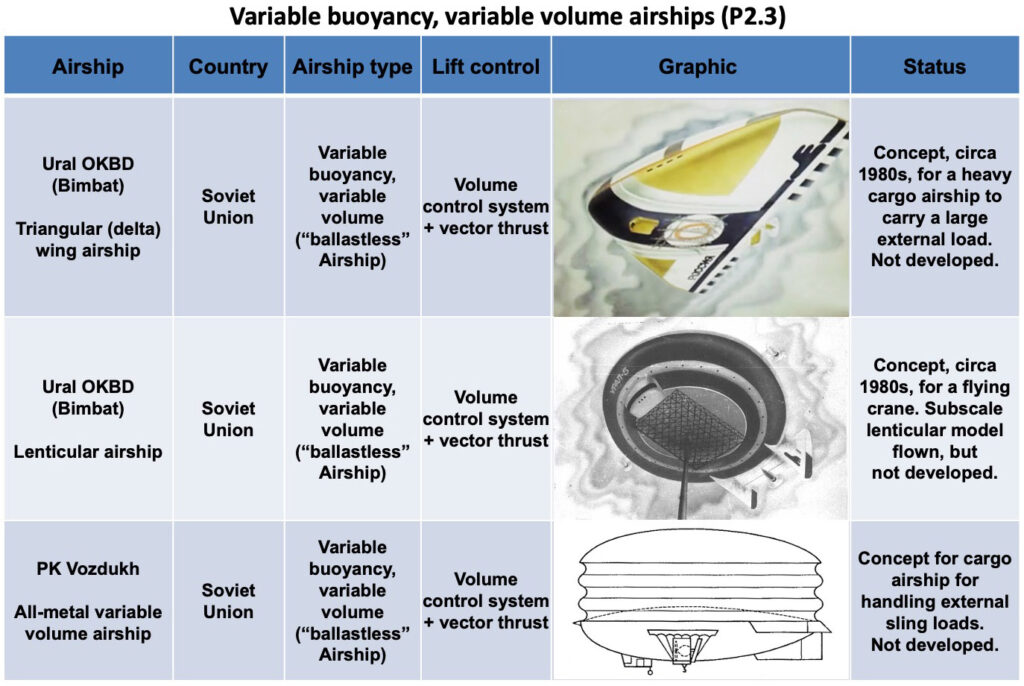

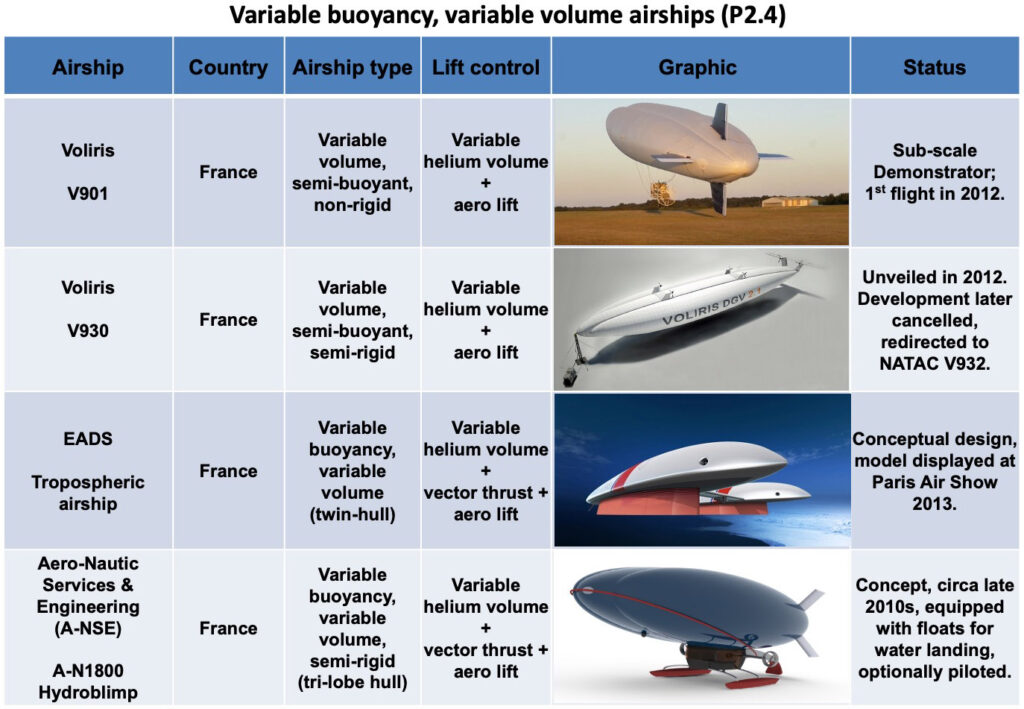

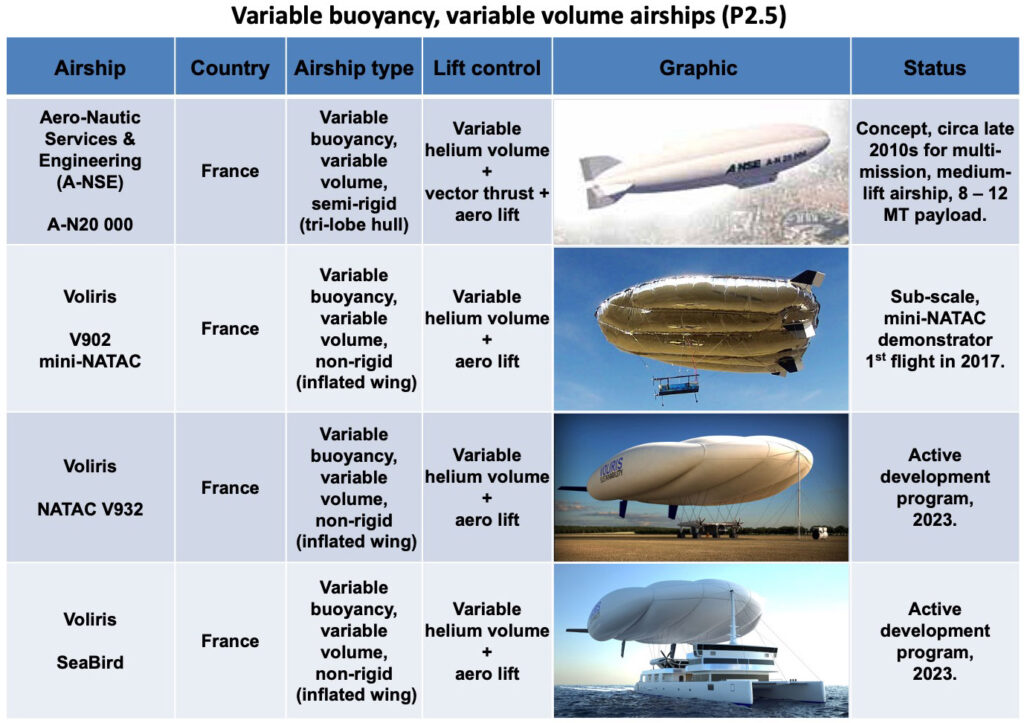

- Variable buoyancy, variable volume airships

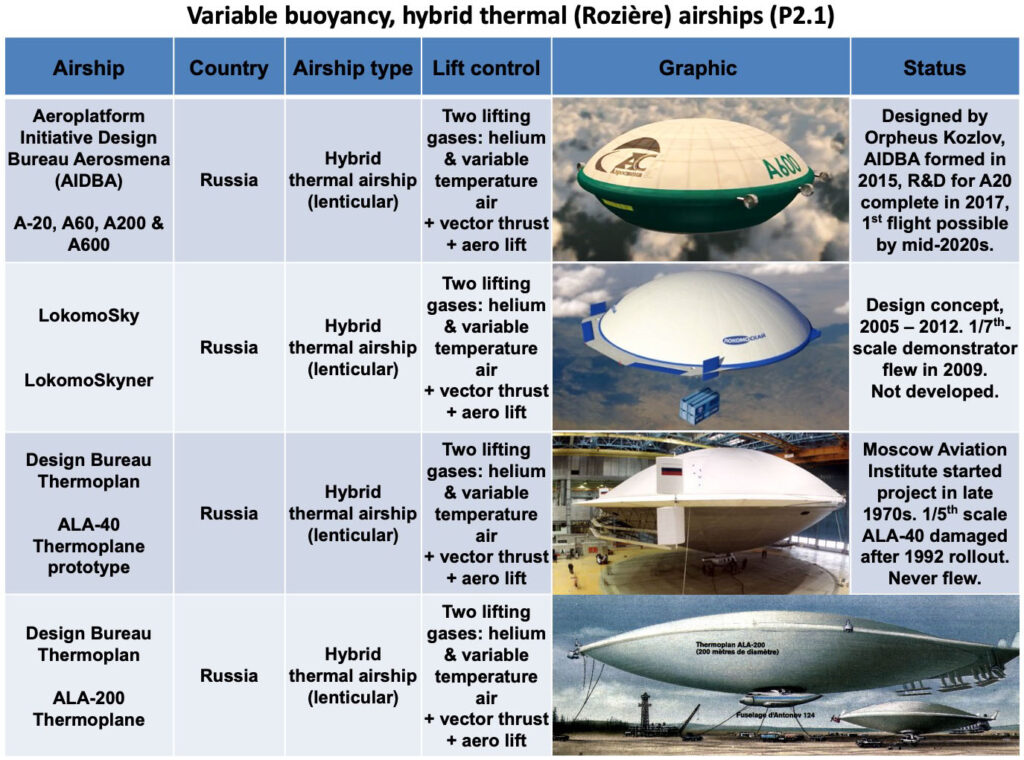

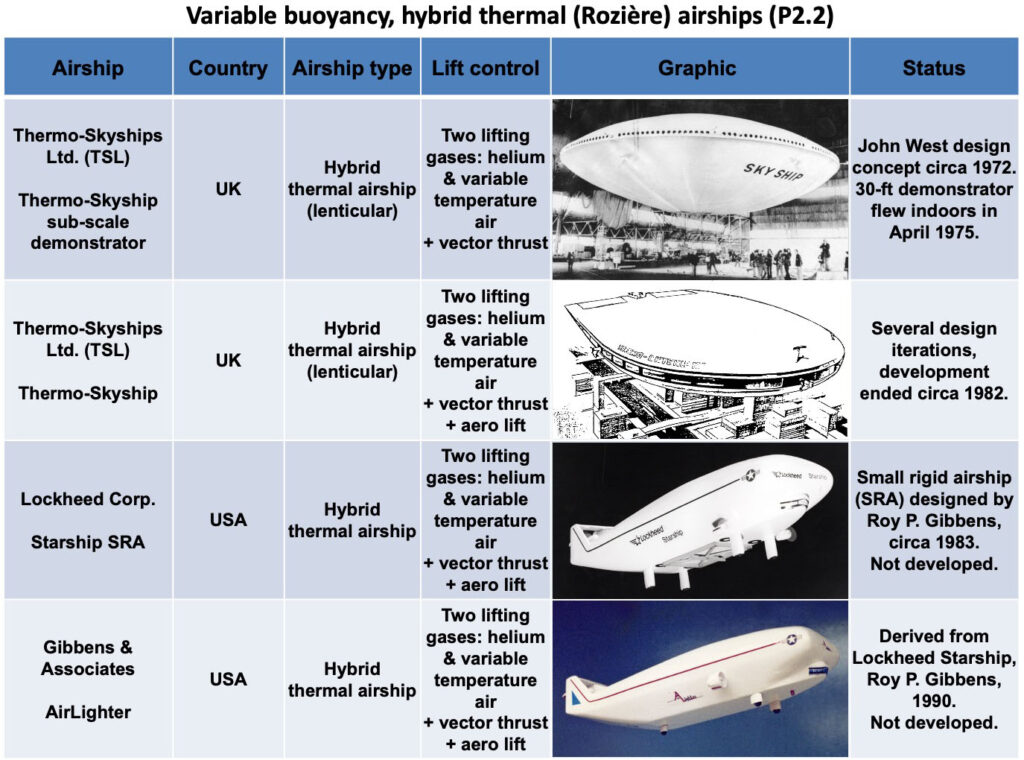

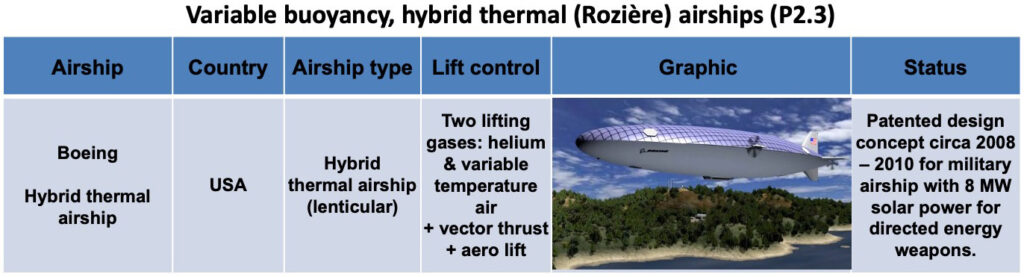

- Variable buoyancy, hybrid thermal-gas (Rozière) airships

- Variable buoyancy propulsion airships / aircraft

- Semi-buoyant hybrid air vehicles

- Semi-buoyant, hybrid airships

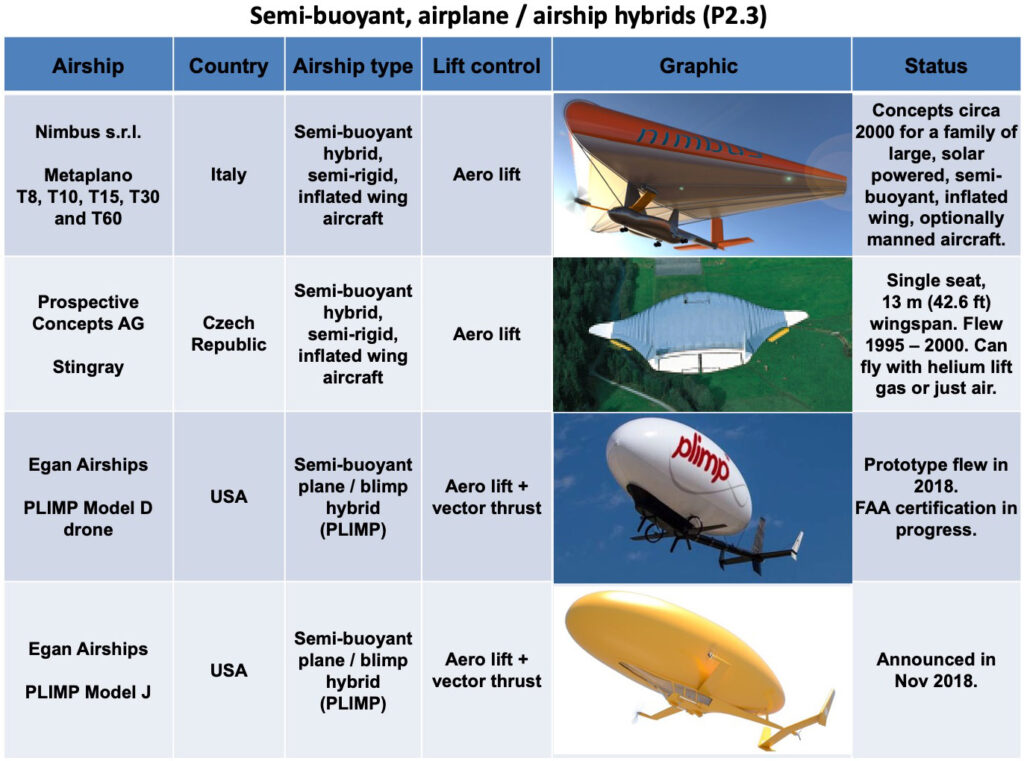

- Semi-buoyant, airplane / airship hybrids (Dynairship, Dynalifter, Megalifter)

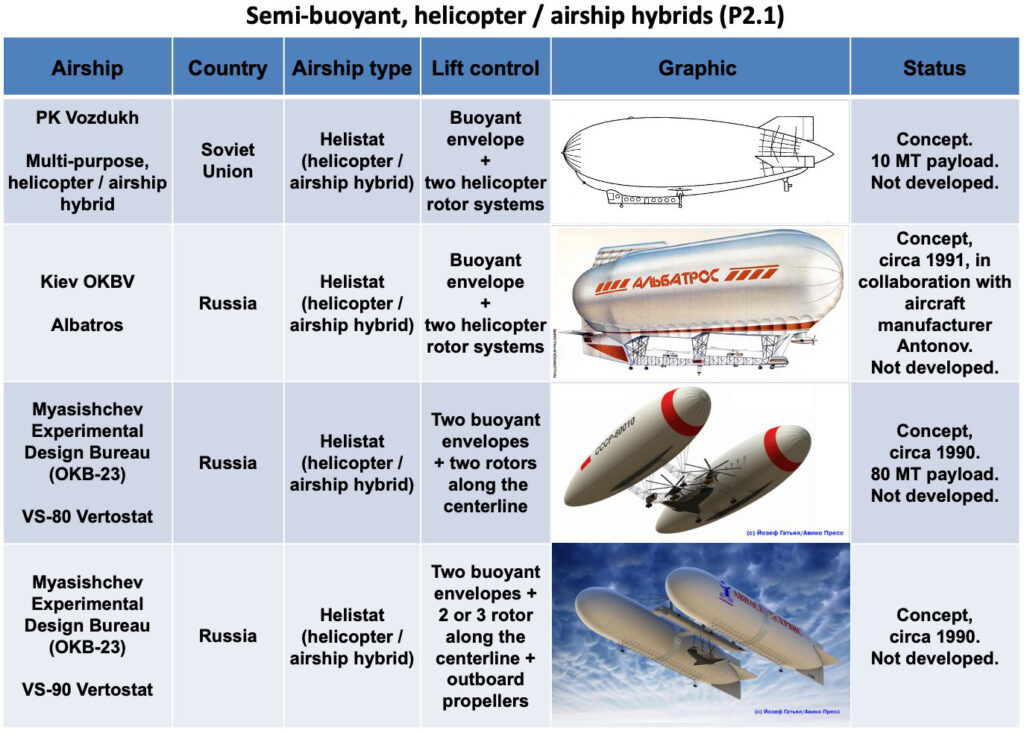

- Semi-buoyant, helicopter / airship hybrids (helistats, Dynastats, rotostats)

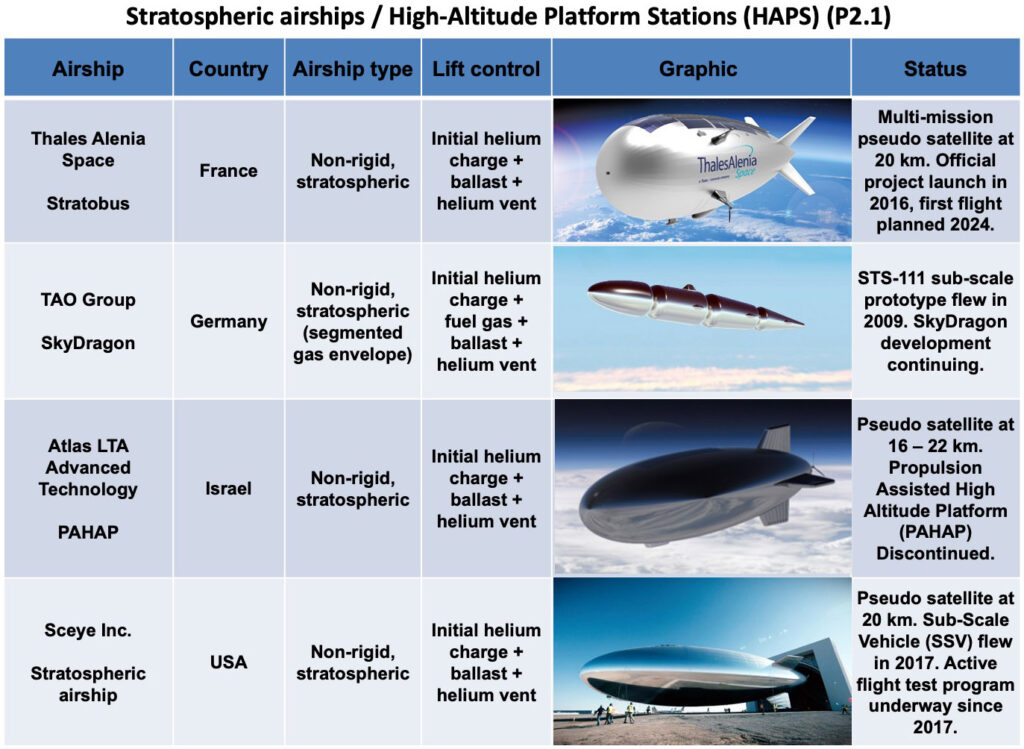

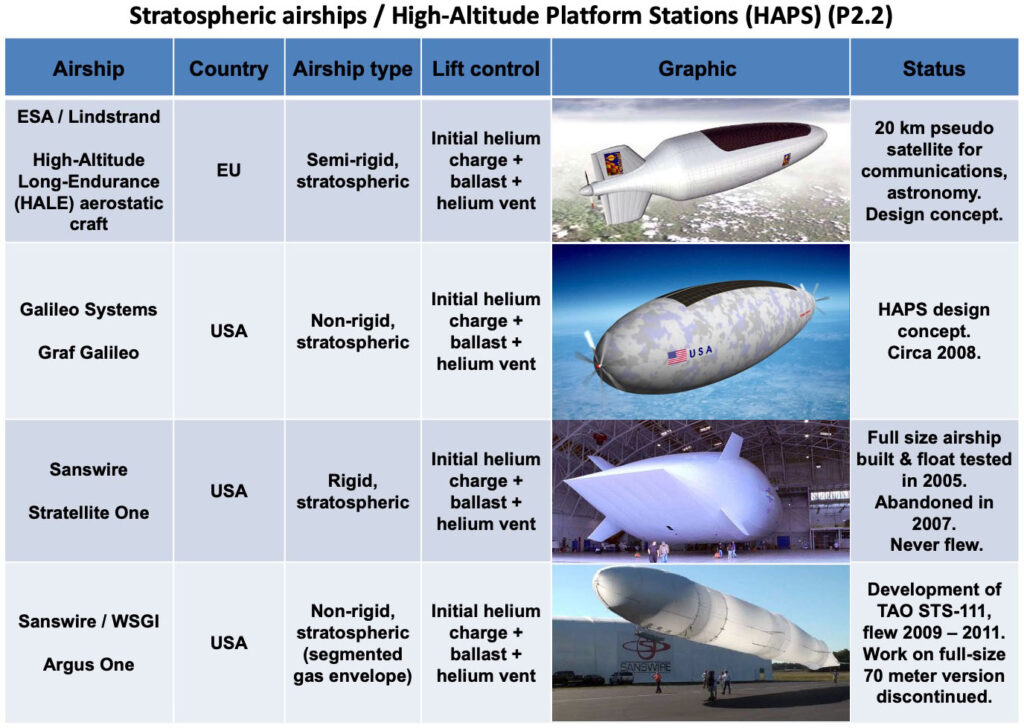

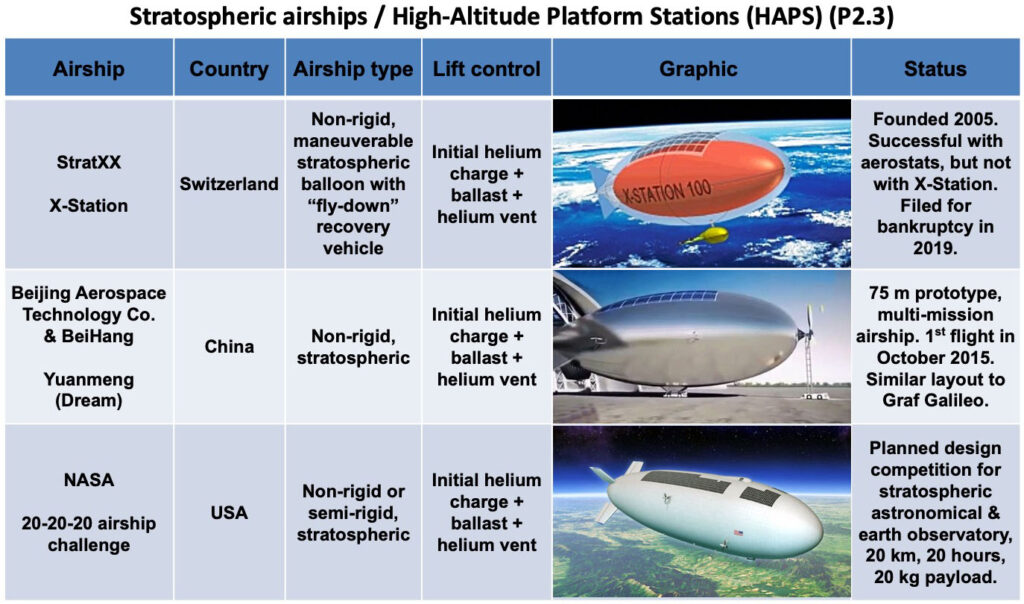

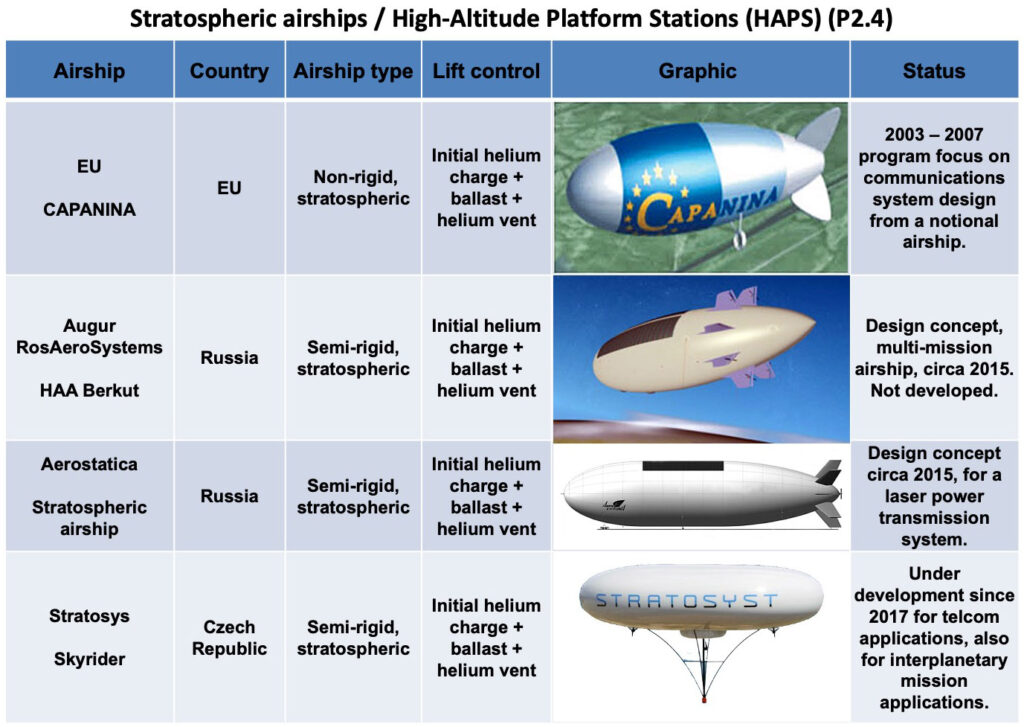

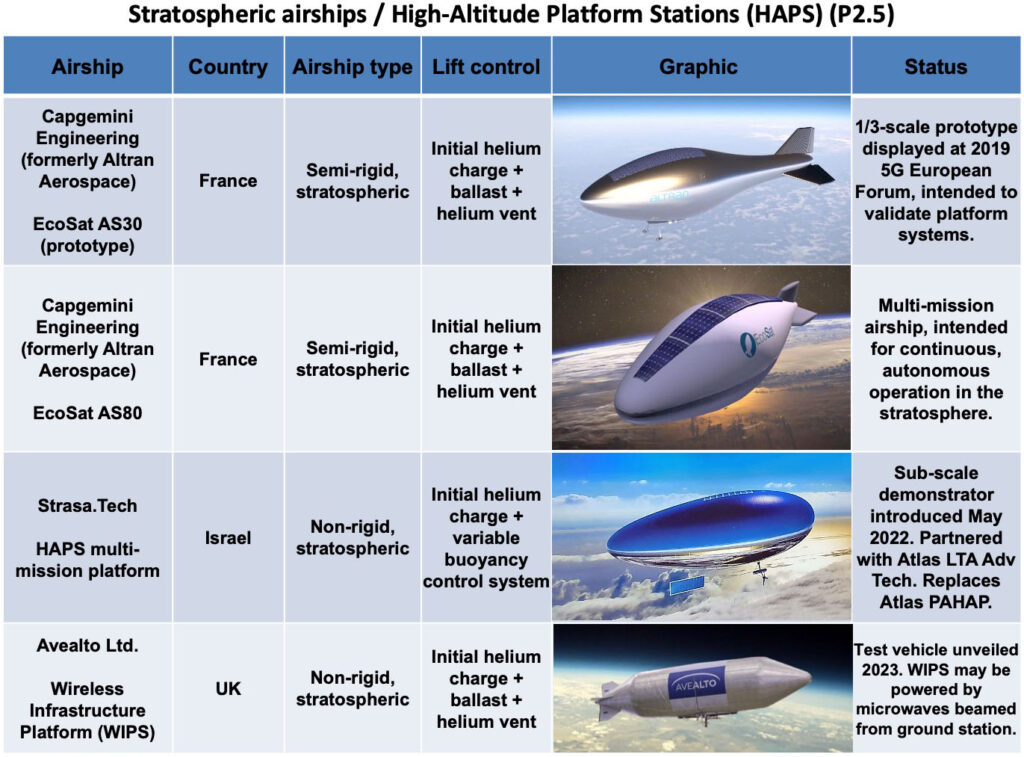

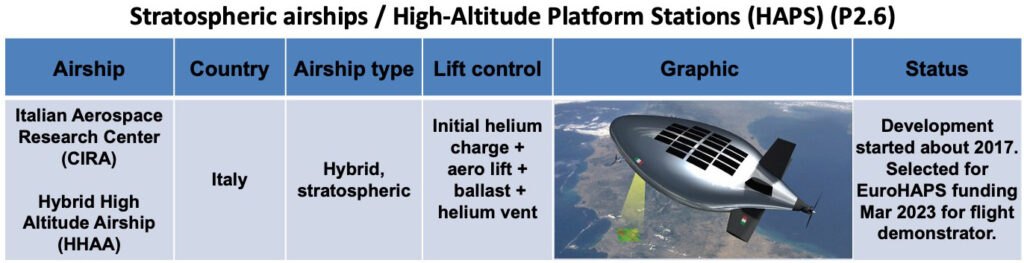

- Stratospheric airships / High-Altitude Platform Stations (HAPS)

- Personal gas airships

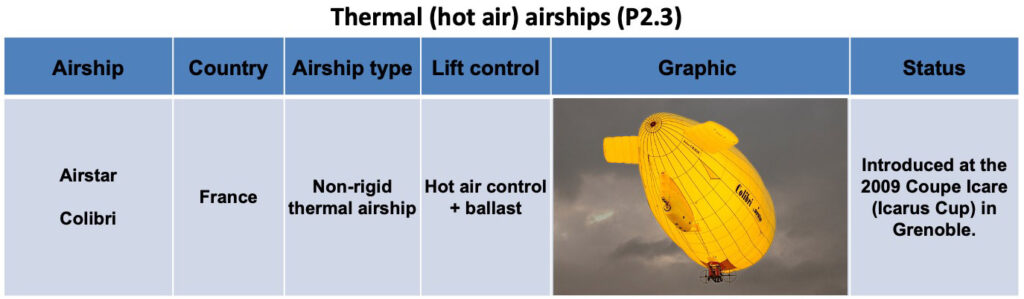

- Thermal (hot air) airships

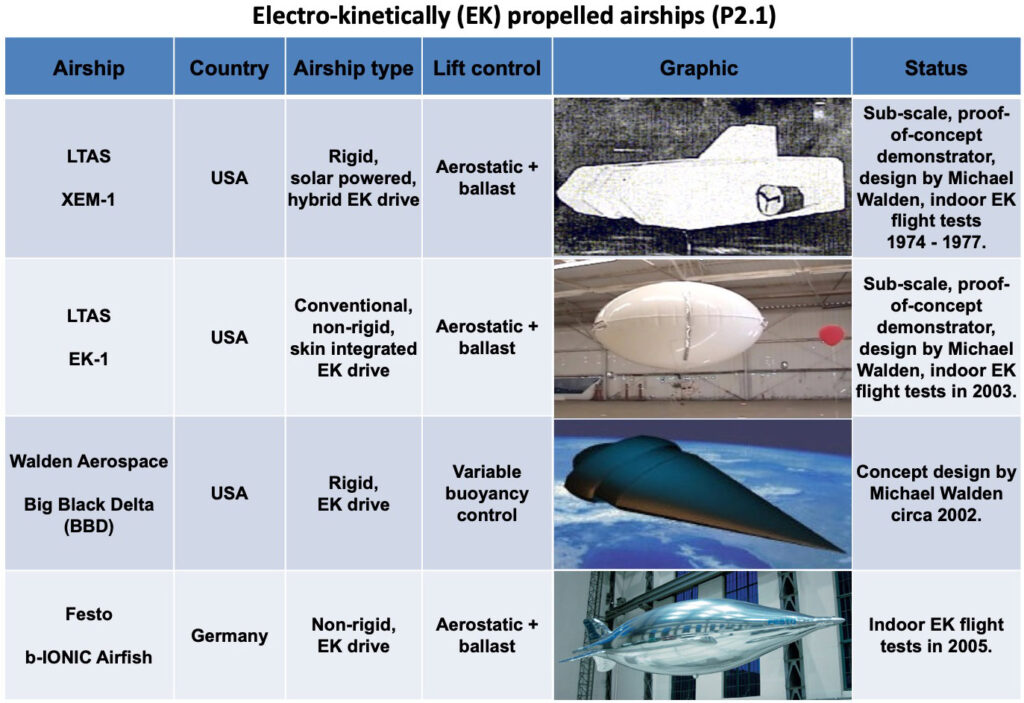

- Electro-kinetically (EK) propelled airships

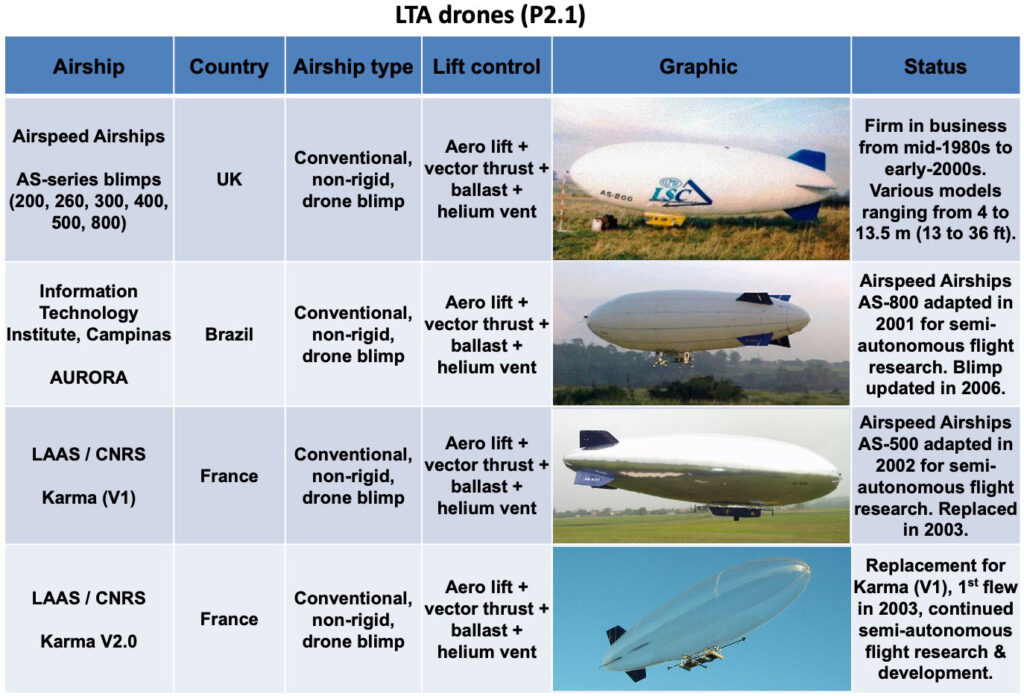

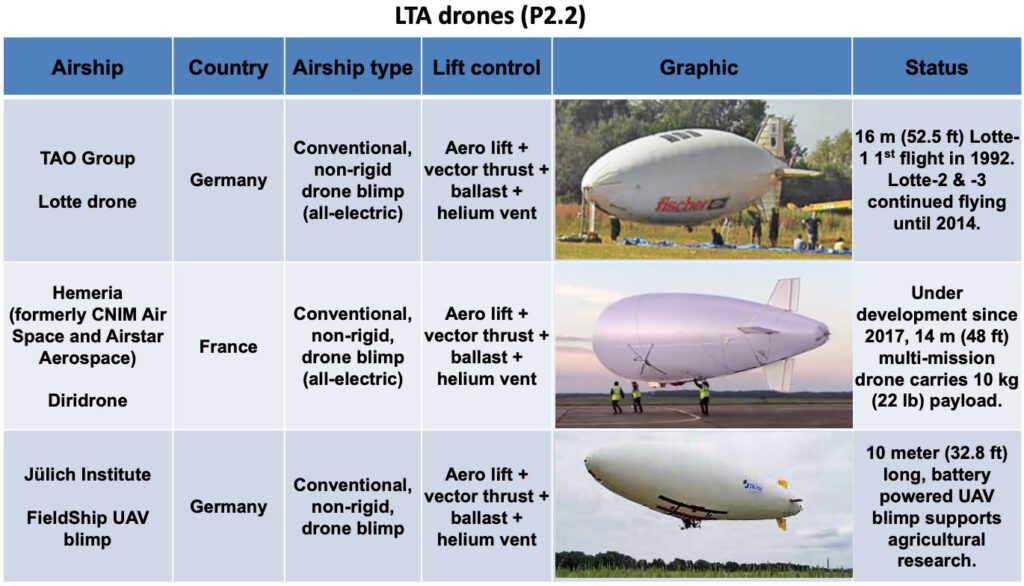

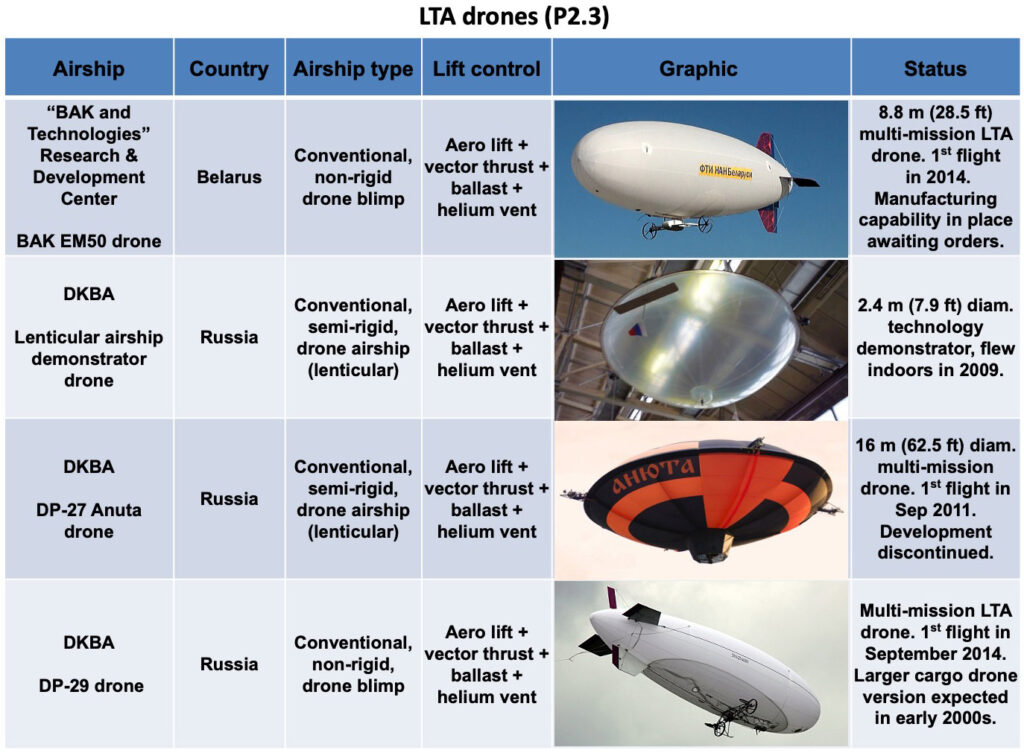

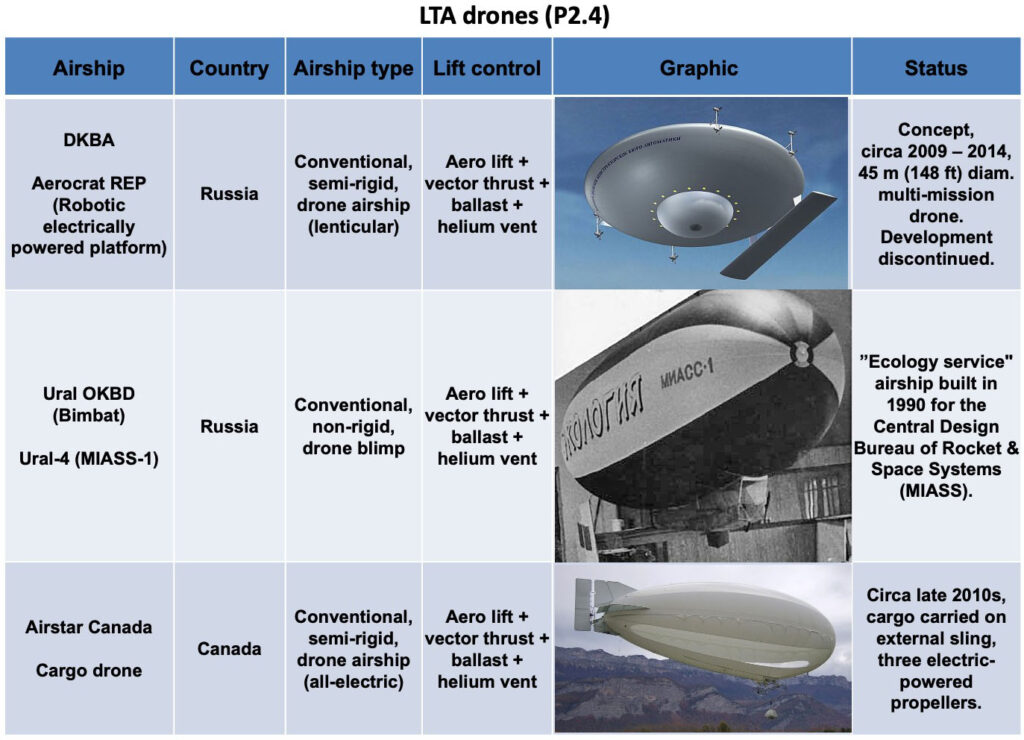

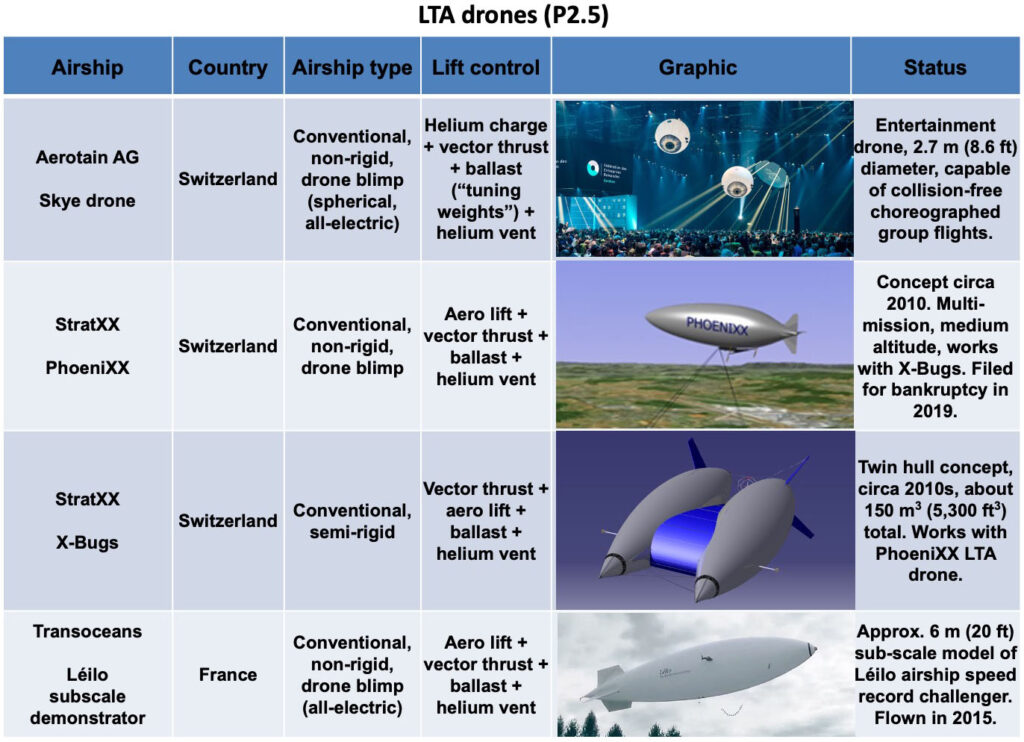

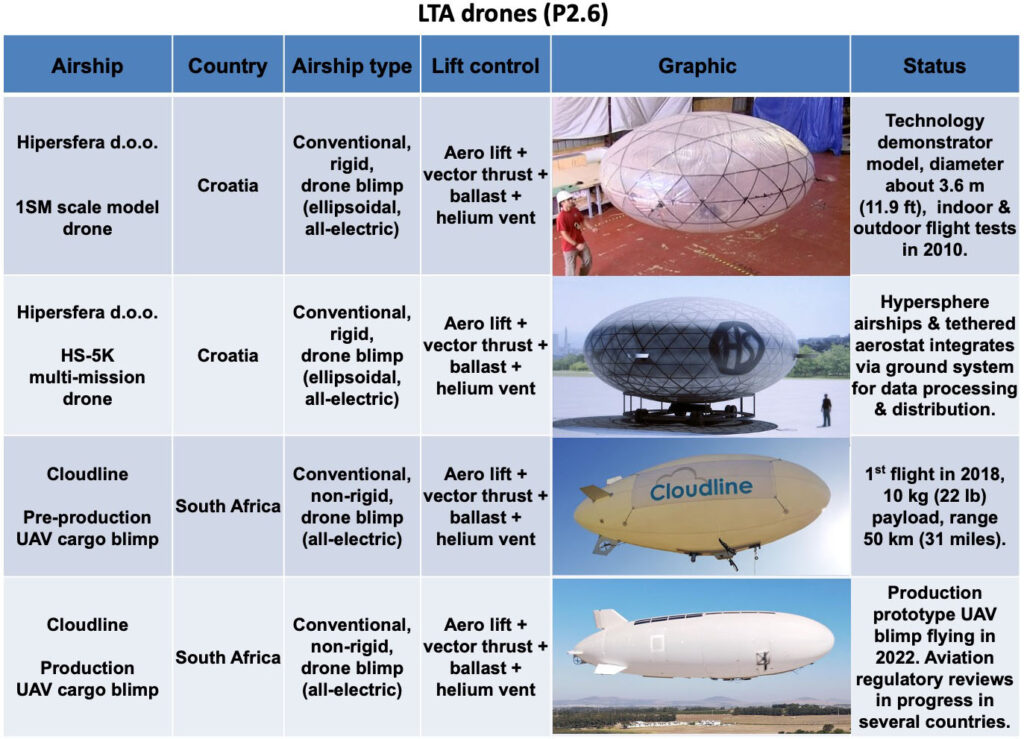

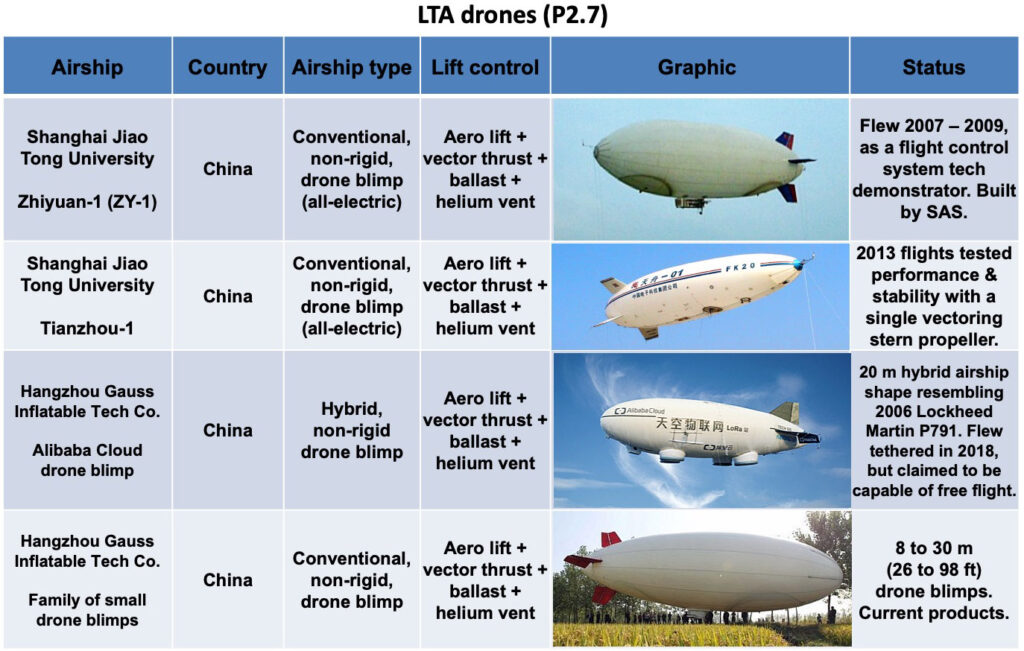

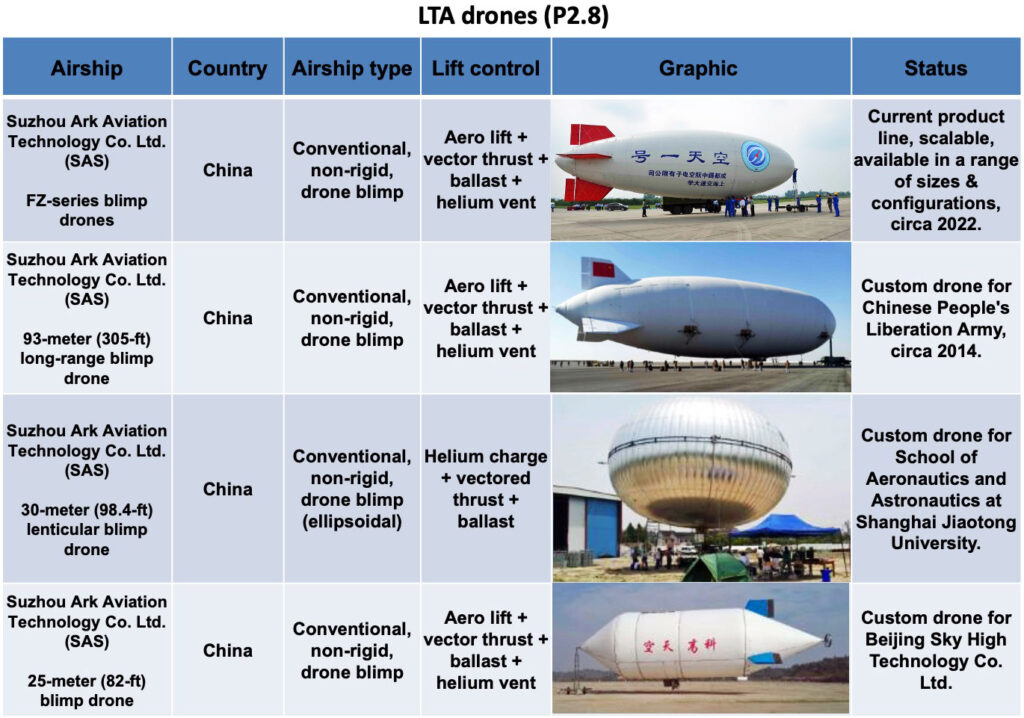

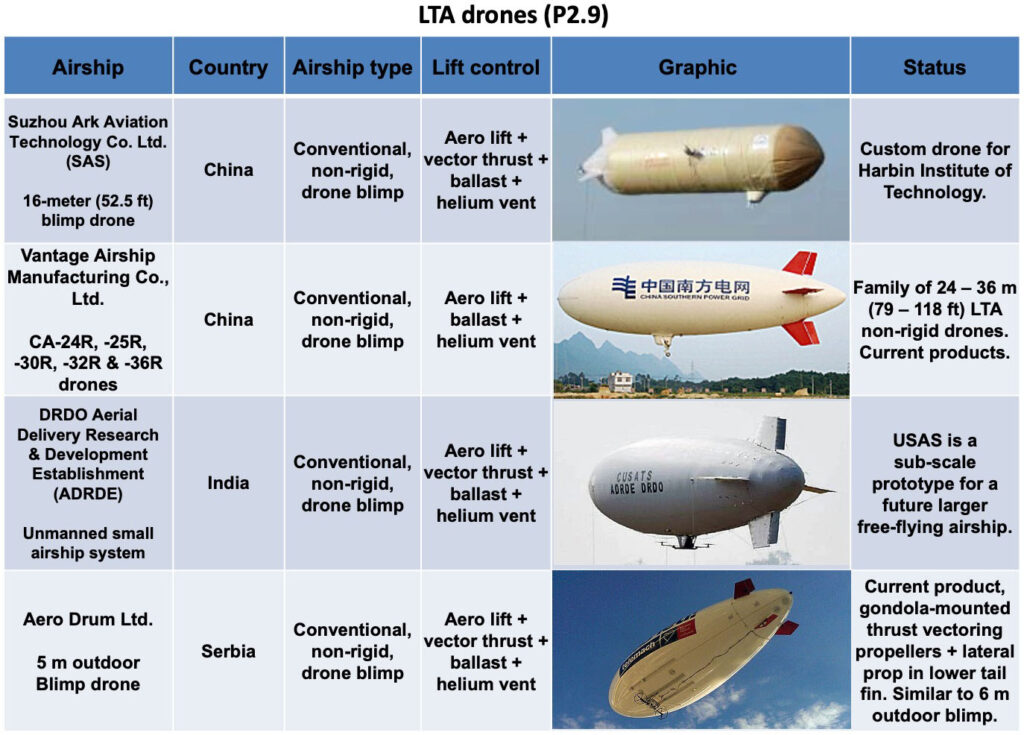

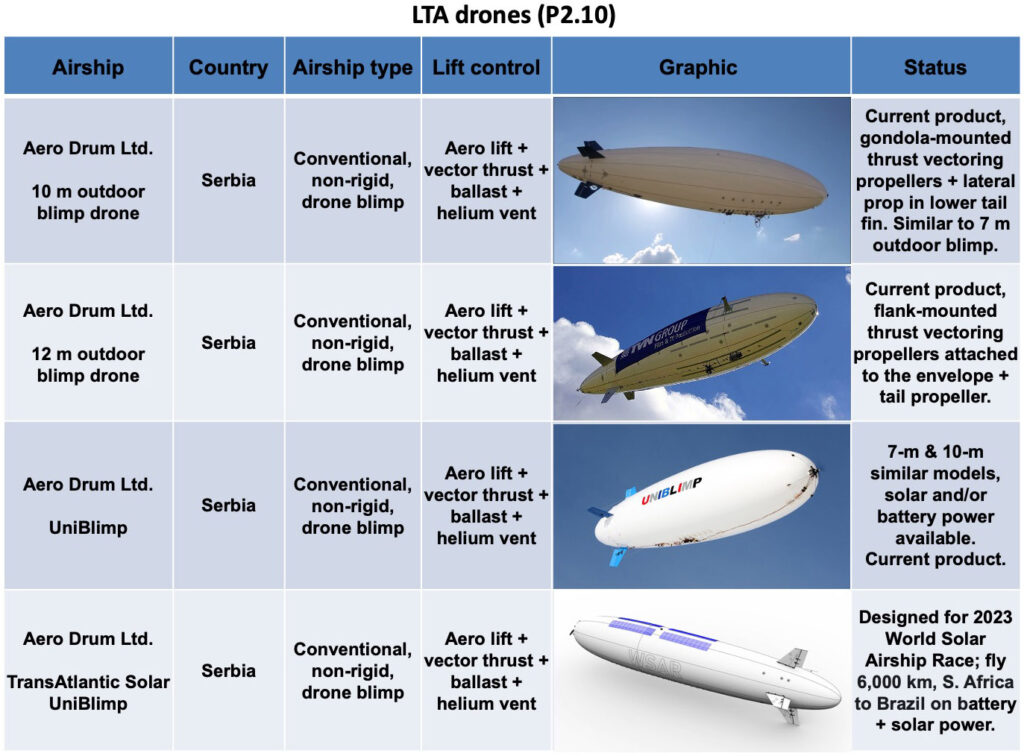

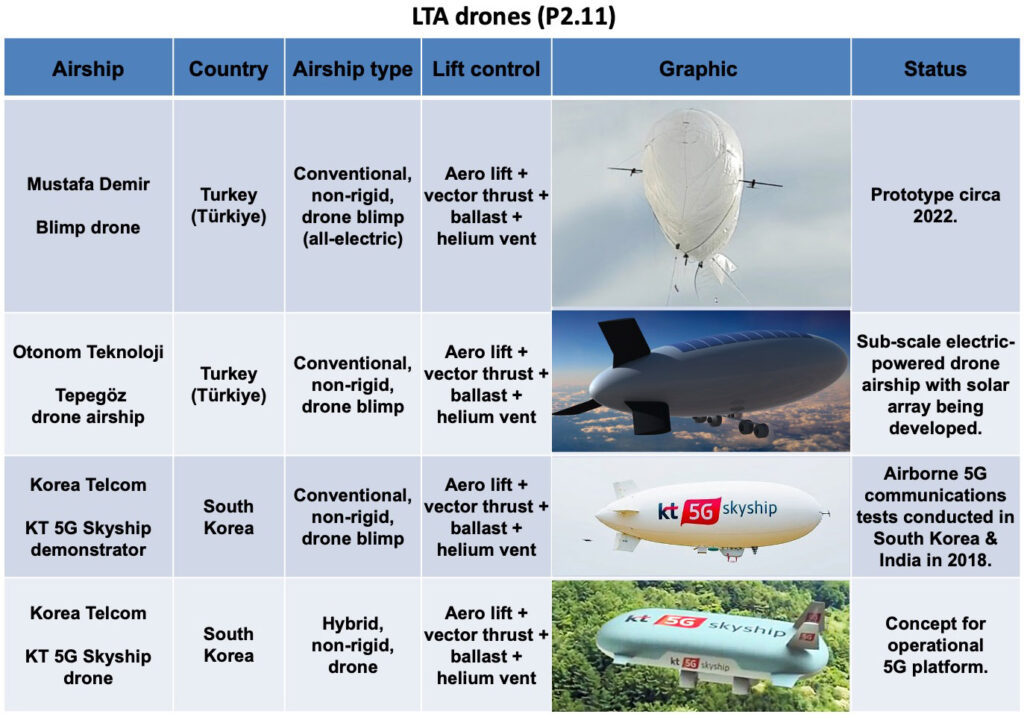

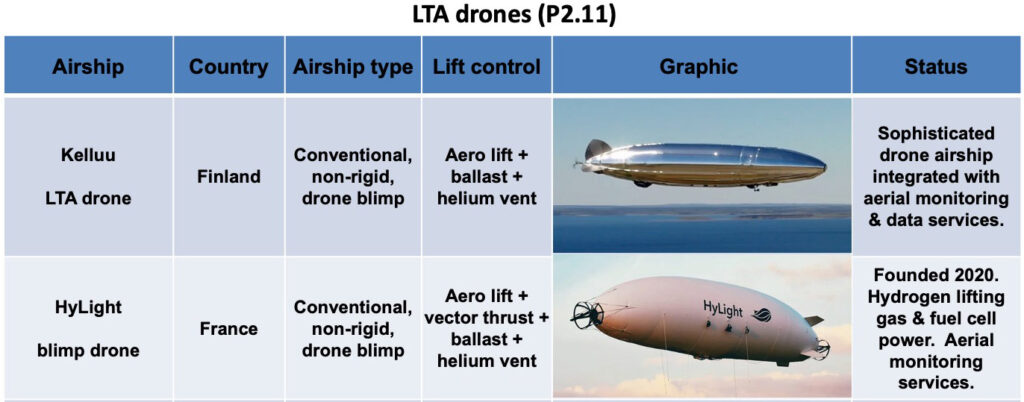

- LTA drones

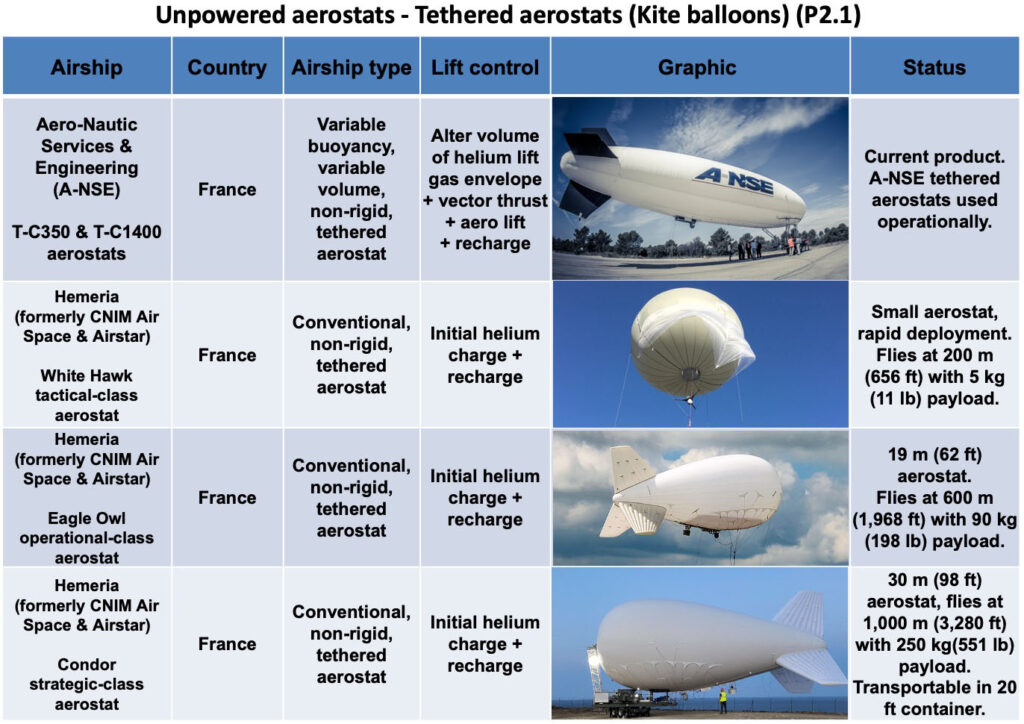

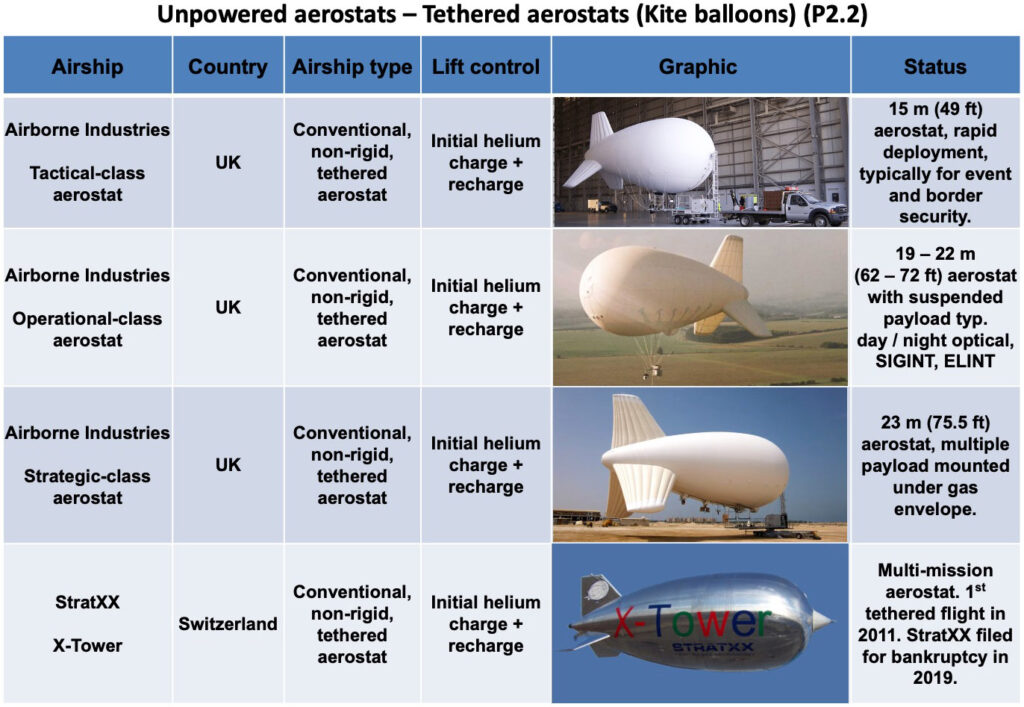

- Unpowered aerostats

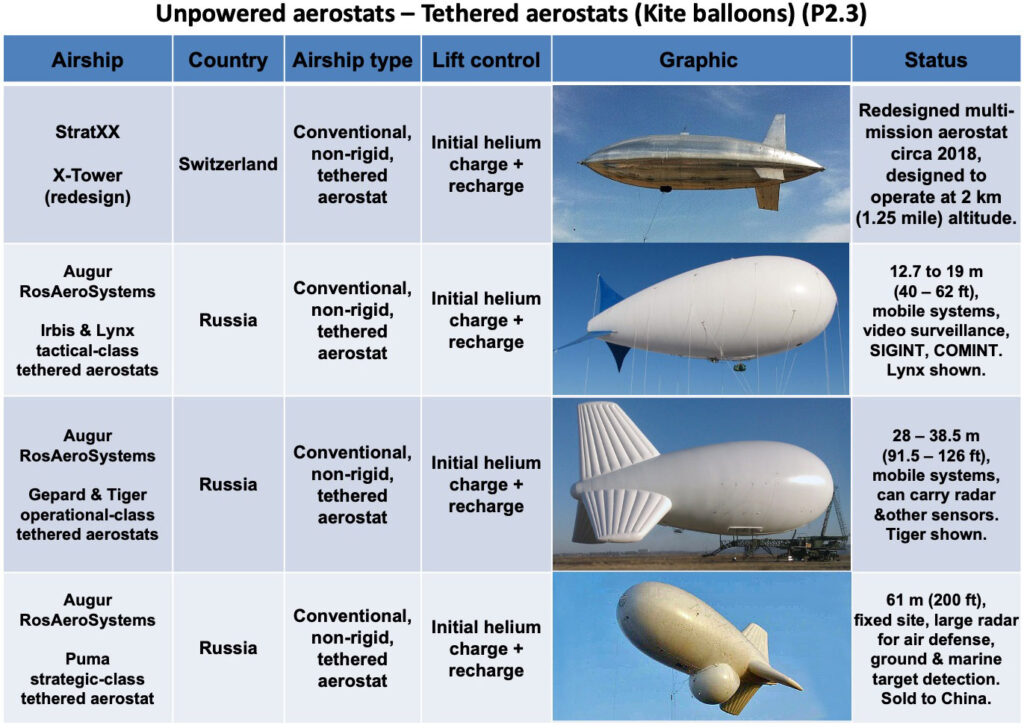

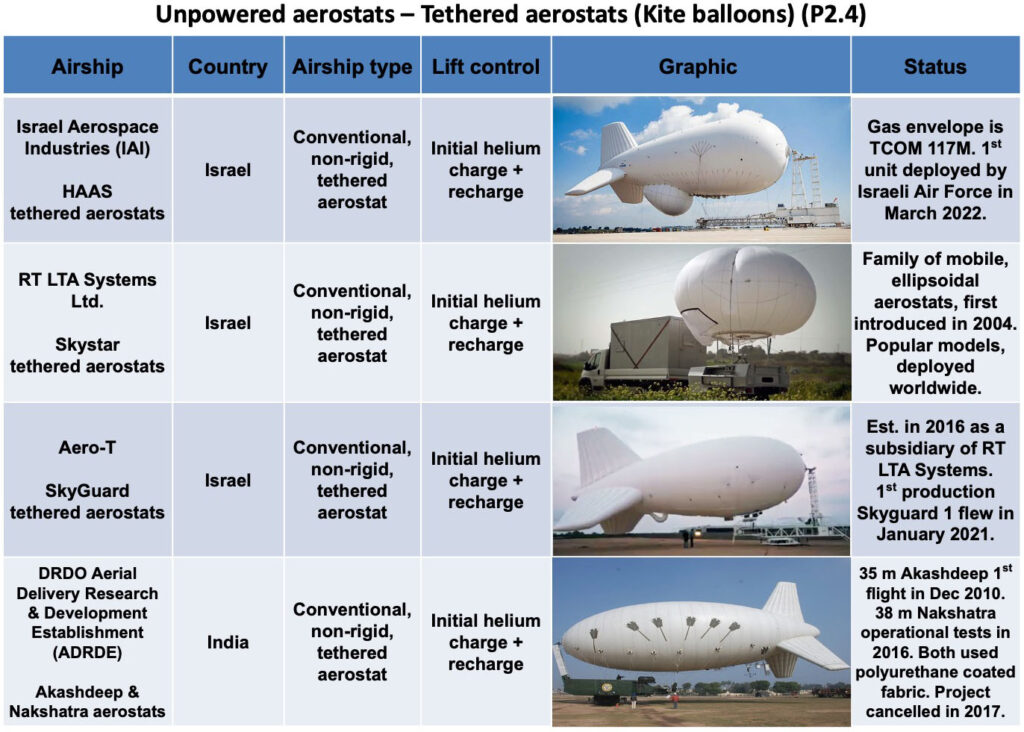

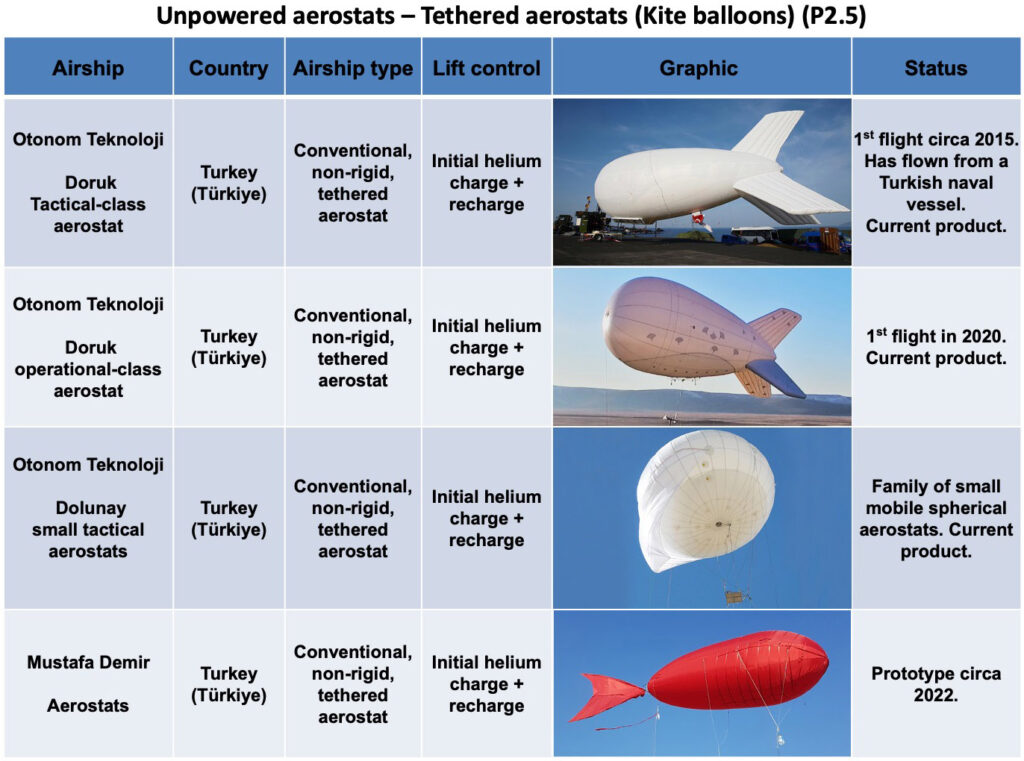

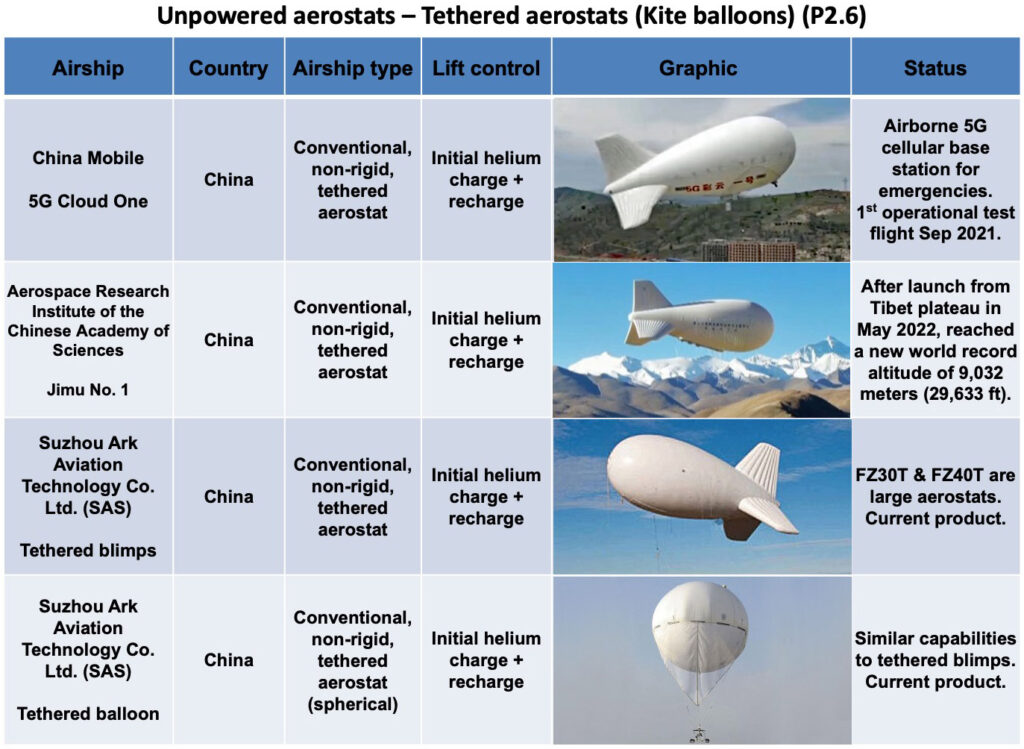

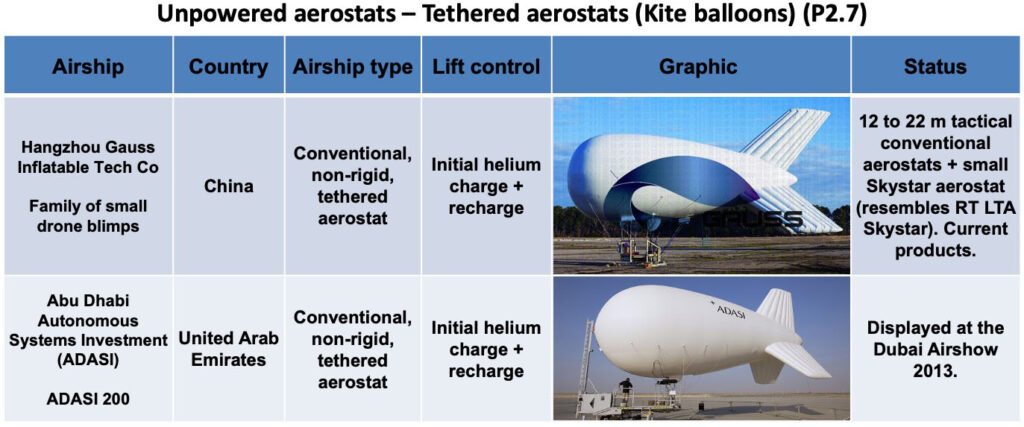

- Tethered aerostats (kite balloons)

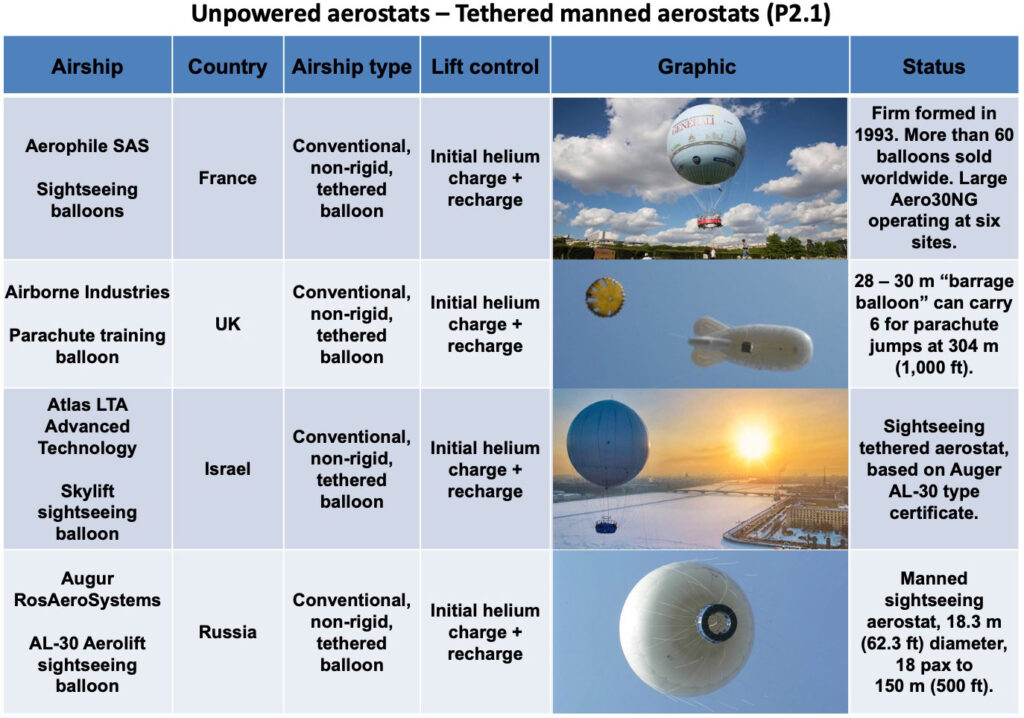

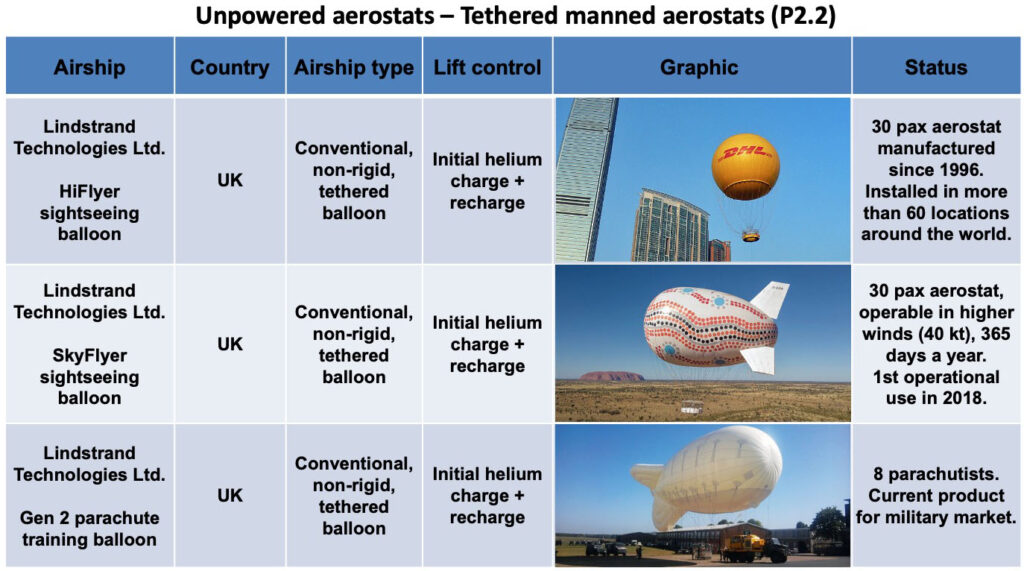

- Tethered manned aerostats

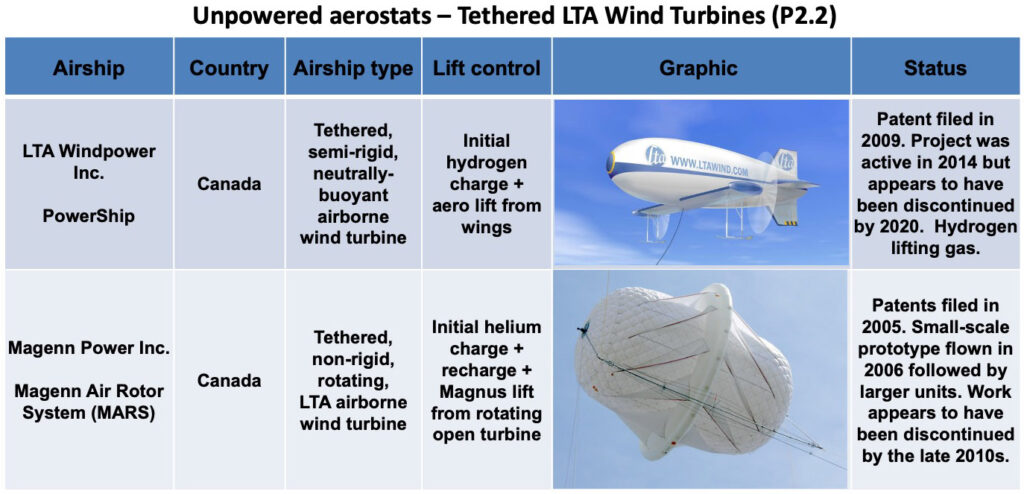

- Tethered LTA wind turbines

- Tethered heavy lift balloons

- Free-flying high-altitude balloons

Within each category, each page of the table is titled with the name of the airship type category and is numbered (P2.x), where P2 = Modern Airships – Part 2 and x = the sequential number of the page in that category. For example, “Conventional, rigid airships (P2.2)” is the page title for the second page in the “Conventional, rigid airships” category in Part 2. There also are conventional, rigid airships addressed in Modern Airships – Part 1. Within a category, the airships are listed in the graphic tables in approximate chronological order.

Links to the individual Part 2 articles on these airships are provided in Section 10. Some individual articles cover more than one particular airship. Have fun exploring!

3. Assessment of near-term LTA market prospects

Among the airships described in Part 2, the following advanced airship seems to be the best candidate for achieving type certification in the next five years:

- Flying Whales (France): The LCA60T rigid cargo airship was significantly redesigned in 2021, which resulted in a considerable schedule delay. In March 2023, Flying Whales reported that they expected to complete construction and flight testing of the first production prototype in the 2024 – 2025 timeframe, followed by EASA certification and start of industrial production in 2026. The project appears to be well funded from diverse international sources in France, Canada, China and Morocco. Full-scale production facilities are planned in France, China and Canada and commercial airship operating infrastructure is being planned.

- Hybrid Air Vehicles (UK): The Airlander 10 commercial passenger / cargo hybrid airship is being developed by HAV based on their experience with the Airlander 10 prototype, which flew from 2016 to 2017. In 2022, Valencia, Spain-based Air Nostrum, which operates regional flights, ordered 10 Airlander 10 aircraft, with delivery scheduled for 2026. Also in 2022, Highlands and Islands Airport (HIAL) sponsored a study for introducing the Airlander 10 in Scotland. In April 2023, the regional UK government of South Yorkshire concluded a financial agreement that is expected to lead to the Airlander 10 being manufactured in Doncaster, in the north of England. Things are moving in the right direction. In March 2023, HAV reported that manufacturing of the first production airship will start in 2023, followed by first flight in 2025 and service entry in 2027.

The following airship manufacturers in Part 2 have advanced designs and they seem to be ready to manufacture a first prototype if they can arrange funding:

- Aerovehicles (USA / Argentina): They claim their AV-10 non-rigid, multi-mission blimp can carry a 10 metric ton payload and be type certified within existing regulations for blimps. This should provide a lower-risk route to market for an airship with an operational capability that does not exist today.

- Atlas LTA Advanced Technology (Israel): After acquiring the Russian firm Augur RosAeroSystems in 2018, Atlas is continuing to develop the ATLANT variable buoyancy, fixed volume heavy lift airship. They also are developing a new family of non-rigid Atlas-6 and -11 blimps and unmanned variants. However, the development plans and schedules have not yet been made public.

- BASI (Canada): The firm has a well-developed design in the MB-30T and a fixed-base operating infrastructure design that seems to be well suited for their primary market in the Arctic.

- Euro Airship (France): The firm reports having production-ready plans for their rigid airship designs. In June 2023, Euro Airship announced plans to build and fly a large rigid airship known as Solar Airship One around the world in 2026.

- Millennium Airship (USA & Canada): The firm has well developed designs for their SF20T and SF50T SkyFreighters, has identified its industrial team for manufacturing, and has a business arrangement with SkyFreighter Canada, Ltd., which would become a future operator of SkyFreighter airships in Canada. In addition, their development plan defines the work needed to build and certify a prototype and a larger production airship.

The promising airships in Part 2, listed above, will be competing in the worldwide airship market with candidates identified in Modern Airships – Part 1, which potentially could enter the market in the same time frame. Among the new airships described in Part 1, the following advanced airship seems to be the best candidates for achieving type certification in the next five years:

- LTA Research and Exploration (USA): Pathfinder 1 rigid airship, which is expected to make its first flight in early 2024. The program appears to be well funded.

The following airship manufacturers in Part 1 have advanced designs and they seem to be ready to manufacture a first commercial prototype if they can arrange adequate funding:

- AT2 Aerospace (USA): Their Z1 hybrid airship formerly was known as the Lockheed Martin LMH-1. In May 2023, Lockheed Martin exited the hybrid airship business without completing type certification and transitioned that business, including intellectual property and related assets, to the newly formed, commercial company AT2 Aerospace. In June, Straightline Aviation (a former LMH-1 customer) signed a Letter of Intent with AT2 Aerospace, signaling commercial support for the Z1 hybrid airship.

- Aeros (USA): It seems that Aeros has been ready for more than a decade to begin type certification and manufacture a prototype of their Aeroscraft ML866 / Aeroscraft Gen 2 variable buoyancy / fixed volume airship. The firm has reported successful subsystem tests.

For decades, there have been many ambitious projects that intended to operate an airship as a pseudo-satellite, carrying a heavy payload while maintaining a geo-stationary position in the stratosphere on a long-duration mission (days, weeks, to a year or more). None were successful. This led NASA in 2014 to plan the 20-20-20 airship challenge: 20 km altitude, 20 hour flight, 20 kg payload. The challenge never occurred, but it highlighted the difficulty of developing an airship as a persistent pseudo-satellite. The most promising new stratospheric airship manufacturers identified in Part 2 are:

- Sceye Inc. (USA): This small firm has built a headquarters and manufacturing facility in New Mexico. Since 2017, it has been developing a mid-size, multi-mission stratospheric airship aimed at demonstrating the ability to deliver communications services to users living in remote regions. A sub-scale vehicle first flew in 2017. Short-duration flights of a prototype stratospheric airship have been conducted since 2021.

- Thales Alenia Space (France): The firm is developing the multi-mission Stratobus. Their latest round of funding from France’s defense procurement agency called for a full-scale, autonomous Stratobus demonstrator airship to fly by the end of 2023, five years later than another demonstrator that was ordered in the original 2016 Stratobus contract, but not built. Thales Alenia Space missed the end of 2023 target and an updated schedule has not yet been announced.

China remains an outlier after the 2015 flight of the Yuanmeng stratospheric airship developed by Beijing Aerospace Technology Co. & BeiHang. The current status of the Chinese stratospheric airship development program is not described in public documents.

Among the many smaller airships identified in Part 2, the following manufacturers could have their airships flying by the mid 2020s if adequate funding becomes available.

- Dirisolar (France): The firm has a well-developed design for their five passenger DS 1500, which is intended initially for local air tourism, but can be configured for other missions. When funding becomes available, it seems that they’re ready to go.

- A-NSE (France): The firm offers a range of aerostat and small airships, several with a novel tri-lobe, variable volume hull design. Such aerostats are operational now, and a manned tri-lobe airship could be flying later in the 2020s.

There has been a proliferation of small LTA drone blimps and other small LTA drone vehicles. Some were developed initially for military surveillance applications, but all are configurable and could be deployed in a range of applications. Some enterprising LTA drone developers also are developing value-adding applications and are offering information services, rather than simply selling a drone to be operated by a customer.

The 2020s will be an exciting time for the airship industry. We’ll finally get to see if the availability of several different heavy-lift airships with commercial type certificates will be enough to open a new era in airship transportation. Aviation regulatory agencies need to help reduce investment risk by reducing regulatory uncertainty and putting in place an adequate regulatory framework for the wide variety of advanced airships being developed. Customers with business cases for airship applications need to step up, place firm orders, and then begin the pioneering task of employing their airships and building a worldwide airship transportation network with associated ground infrastructure. This will require consistent investment over the next decade or more before a basic worldwide airship transportation network is in place to support the significant use of commercial airships in cargo and passenger transportation and other applications. Perhaps then we’ll start seeing the benefits of airships as a lower environmental impact mode of transportation and a realistic alternative to fixed-wing aircraft, seaborne cargo vessels and heavy, long-haul trucks.

4. Links to the individual articles

The following links will take you to the individual articles that address all of the airships identified in the preceding graphic table.

Note that a few of these articles address more than one airship design from the same manufacturer / designer and they may be in different categories (i.e., Augur RosAeroSystems, Atlas LTA Advanced Technology). These designs are listed separately in the above graphic tables and the following index. The links listed below will take you to the same article.

CONVENTIONAL AIRSHIPS

Conventional, rigid airships

- Aerostatica / RosAeroSystems – A-06: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Aerostatica-converted.pdf

- Augur RosAeroSystems (RAS) – DZ-N1 & MD-900: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Augur-RosAeroSystems_R2-converted-compressed.pdf

- Buoyant Aircraft Systems International (BASI) – MB-30T & -100T: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/BASI.pdf

- Flying Whales – LCA60T: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Flying-Whales_R2-converted-compressed-1.pdf

- FlyWin – demonstrator airship: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/FlyWin-airships-converted.pdf

- Gibbens & Associates – AirLighter 2 and cycloidal propellers: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Gibbens-Assoc_AirLighter-Cy-Prop.pdf

- Leningrad OKB – heavy-lift rigid airships: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Leningrad-OKB-airships-converted.pdf

- Lightspeed USA Inc. – Lightships LS-12 & -60: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Lightspeed-USA-converted.pdf

- Solar Flight – Sunship: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Solar-Flight_Sunship_R1-converted-1.pdf

- The Hamilton Airship Company (THAC) – HA-44, -80 & -140: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Hamilton-Airships-converted.pdf

- TP Aerospace – Atlas 80: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/TP-Aerospace_Atlas-80_R1-converted.pdf

- Transoceans – Léilo, Trans-Mediterranean & Trans-Atlantic airships: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Aerial-Concept-Group-Transoceans-converted.pdf

Conventional, semi-rigid airships

- Aere Airships: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Aere-Airships.pdf

- Airstar – Alpha: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Alpha-Alize-converted.pdf

- Capgemini Engineering (formerly Altran Aerospace) – Sun Cloud: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Capgemini-Engg_Altran-Aerospace-solar-airships-converted.pdf

- LTA Corp. – Alizé: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Alpha-Alize-converted.pdf

- SkyLifter Ltd. – Flying Crane, SL150, SL50, SL25 & SL20: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Skylifter_R1-converted-compressed.pdf

- SolarAirShip – High-Speed Solar Airship (HSSA): https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Helios_SolarAirShip_High-Speed-Solar-Airship_HSSA.pdf

Conventional, non-rigid airships (blimps)

- 21st Century Airships – Voyager: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/21st-Century-_Voyager-converted.pdf

- 21st Century Airships & Techsphere – spherical blimps: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/21st-Century-Techsphere-converted.pdf

- Aérial Concept Group & Transoceans – IRIS Challenger I & II: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Aerial-Concept-Group-Transoceans-converted.pdf

- Aerostatica – 01, 02 & 300: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Aerostatica-converted.pdf

- Aerovehicles, Inc. (AVI) – AV-10 blimp: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/AeroVehicles_Aerocat_R1-converted.pdf

- Atlas LTA Advanced Technology – Atlas-6 and -11 blimps: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Atlas-LTA-Advanced-Technology-airships-converted.pdf

- Augur RosAeroSystems (RAS) – MA-55, PD-300, Au-11, -12M. -30 & SOKOL: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Augur-RosAeroSystems_R2-converted-compressed.pdf

- Aviation Industry Corporation of China (AVIC) – AS700: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/AVIC_AS700.pdf

- DKBA conventional airships – 2DP & DP-6000 blimps: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/DKBA-conventional-airships-converted.pdf

- E-Green Technologies (EGT) – Bullet 125 & 580: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/EGT_Bullet-converted.pdf

- Myasishchev Experimental Design Bureau (OKB-23) – 2AB & Cruise-1 blimps:http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Myasishchev-Design-Bureau-airships-converted.pdf

- Ural OKBD (Bimbat) – cargo blimp: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Bimbat-Ural-OKBD-airships-converted.pdf

- Vantage Airship Manufacturing Co. – blimps: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Vantage-Airship_R2-converted.pdf

- Voliris V900: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Voliris_R1-converted-compressed.pdf

VARIABLE BUOYANCY AIRSHIPS

Variable buoyancy, fixed volume airships

- AeroVehicles, Inc. (AVI) – Minicat, Aerocat R-12 & R-40: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/AeroVehicles_Aerocat_R1-converted.pdf

- Airship-GP – “Super Hybrid” AeroTruck, AeroBoat & AeroYacht: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Airship-GP_R1-converted.pdf

- Atlas LTA Advanced Technology – ATLANT 30, 100 & 300: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Atlas-LTA-Advanced-Technology-airships-converted-compressed.pdf

- Augur RosAeroSystems (RAS) – ATLANT: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Augur-RosAeroSystems_R2-converted-compressed.pdf

- Euro Airship – 10T, 50T, 400T & Solar Airship One: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Euro-Airship.pdf

- Global Airships – Atlas: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Global-Airships_Atlas_R1-converted.pdf

- H2 Clipper Inc. – H2 Clipper hydrogen transport: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/H2-Clipper-converted-1.pdf

- Imaginactive – Alert, Invitation & Kugaaruk: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Imaginactive_-Alert-Invitation-Kugaruuk-converted-compressed.pdf

- Kiev OKBV – D-1: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Kiev-OKBV-airships-converted.pdf

- Krylo Design Bureau – SHa-2000: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Shalaev-Krylo-Design-Bureau-airships-converted.pdf

- LTA Aerostructures – 10T & 70T: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/LTA-Aerostructures_R1-converted.pdf

- Skylite Aeronautics – GeoShip: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Skylite-Aeronautics_GeoShip_R1-converted.pdf

- Third Dimension Project – SHa-3500: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Third-Dimension-Project-converted.pdf

- Varialift Plc. – ARH-PT, ARH 50 & 250: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Varialift-Airships.pdf

Variable buoyancy, variable vacuum airships

- Anumá Aerospace Corp. – partial-vacuum airship: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Anuma-Aerospace-converted.pdf

- Ilia Toli – partial-vacuum airship: Coming in 2024

Variable buoyancy, variable volume airships

- A-NSE – tri-lobe airships & aerostats: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/A-NSE.pdf

- Arthur Clyde (A.C.) Davenport – Dynapod: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Dynapod_R1-converted.pdf

- EADS – Tropospheric Airship: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/EADS_Tropospheric-Airship_R1-converted.pdf

- PK Vozdukh – all-metal, variable volume airship: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/PK-Vozdukh-airships-converted.pdf

- Ural OKBD (Bimbat) – Ural-2, Ural-3, Double hull airship, Horizontal wing airship, Lenticular airship, Triangular (delta) wing airship, Vertical wing airship:http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Bimbat-Ural-OKBD-airships-converted.pdf

- Voliris V901, V902, V930, V932 NATAC & SeaBird: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Voliris_R1-converted-compressed.pdf

Variable buoyancy, hybrid thermal-gas (Rozière) airships

- Aerosmena (AIDBA) – A20, A-60, A200 & A600: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Aerosmena_hybrid-thermal-airships-converted.pdf

- Boeing – hybrid thermal airship: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Boeing_hybrid-thermal-airship-converted-1.pdf

- Design Bureau Thermoplan – Thermoplane ALA-40 & -200: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Thermoplan_hybrid-thermal-airships-converted.pdf

- Gibbens & Associates – AirLighter and cycloidal propellers: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Gibbens-Assoc_AirLighter-Cy-Prop.pdf

- Lockheed Corp. – Starship hybrid thermal small rigid airship (SRA): https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Lockheed_Starship-SRA.pdf

- LocomoSky – LokomoSkyner: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/LocomoSky_hybrid-thermal-airships-converted.pdf

- Thermo-Skyships Ltd. (TSL) – Thermo-Skyship: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Thermo-Skyships_hybrid-thermal-airships_R1a-converted-compressed.pdf

Variable buoyancy propulsion airships

- Hunt Aviation – Gravity Plane: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Hunt-Aviation-Gravity-Plane-converted.pdf

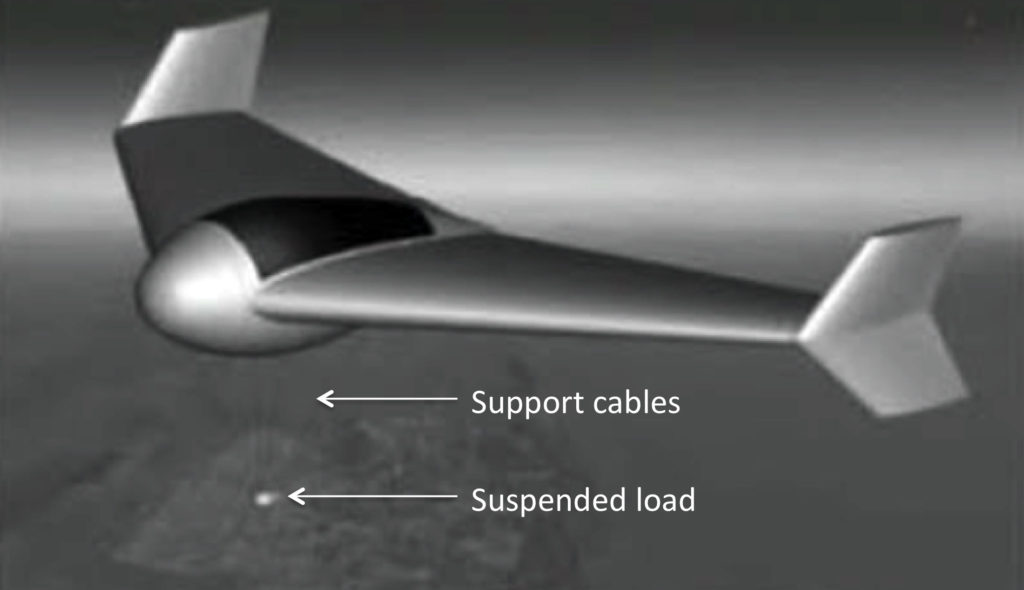

- New Mexico State University – Advanced High-Altitude Aerobody (AHAB): https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/New-Mexico-State-University_AHAB_R1-converted.pdf

- Phoenix: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Phoenix.pdf

- Solomon Andrews – Aereon & Aereon 2 (1863): http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Solomon-Andrews_Aereon-Aereon-II-converted.pdf

- Utah Aereon Corp. – Aereon SA-1: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Utah-Aereon-Corp_Aereon-SA-1.pdf

- Walden Aerospace / LTAS – HY-SOAR B.A.T & VAMPIRE: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Walden-LTAS_VB-propelled-airships_R1-converted.pdf

SEMI-BUOYANT AIR VEHICLES

Semi-buoyant, hybrid airships

- Airship-GP – AeroTruck, AeroBoat & AeroYacht: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Airship-GP_R1-converted.pdf

- Chinese Academy of Sciences – Hybrid airship for Airborne Electromagnetic (AEM) surveys: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/China-hybrid-airship-for-AEM-surveys.pdf

- Dirisolar – DS 0.6, DS 12, DS 900, DS 1500 & DS 30: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Dirisolar.pdf

- Dolphin Luftschiff: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Dolphin-Luftschiff-converted.pdf

- Flying-Yacht: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Flying-Yacht_R1-converted.pdf

- Kamov Company – Aerolet: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Kamov_Aerolet-converted.pdf

- Krylo Design Bureau – SHa-10b: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Shalaev-Krylo-Design-Bureau-airships-converted.pdf

- Magnus Aerospace Corp. – LTA 20-1 spherical Magnus effect airship: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Magnus-Aerospace_spherical-airship-converted-compressed.pdf

- MBDA – Armatus airship: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/MBDA_CVS301-Vigilus_Amantus-airship-converted.pdf

- Millennium Airship – SkyFreighter SF20T, SF50T & SF500T: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Millennium-Airship_SkyFreighter-R1-converted.pdf

- Nautilus SpA – Elettra Twin Flyers (ETF): https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Nautilus_Elettra-Twin-Flyers_R1-converted.pdf

- Turtle Airships: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Turtle-Airships-converted-1.pdf

- Vantage Airship Manufacturing Co., Ltd. – CA-60T & CA-200T: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Vantage-Airship_R2-converted.pdf

Semi-buoyant, airplane / airship hybrids

- Egan Airships – PLIMP Model D drone & Model J: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Egan-Airships_PLIMP_R1-converted.pdf

- Nimbus – Eos Xi & Metaplano inflated wing aircraft: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Nimbus-srl_EosXi-Metaplano-converted.pdf

- Prospective Concepts AG – Stingray: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Prospective-Concepts-AG_Stingray-converted.pdf

- Solar Ship – Semi-buoyant aircraft: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Solar-Ship_R1-converted.pdf

- Tumencotrans – BARS & Bella-1: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Tumenecotrans_BARS-Bella-1-converted-compressed.pdf

- Tumenecotrans – Rescue sloop & “Micro” RVK: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Third-Dimension-Project-converted.pdf

- Ural OKBD (Bimbat) – Hybrid winged airship: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Bimbat-Ural-OKBD-airships-converted.pdf

Semi-buoyant, helicopter / airship hybrids

- Kiev OKBV – Albatros: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Kiev-OKBV-airships-converted.pdf

- Myasishchev Experimental Design Bureau (OKB-23) – VS-80 & VS-90 Vertostats: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Myasishchev-Design-Bureau-airships-converted.pdf

- PK Vozdukh – multi-purpose, helicopter / airship hybrid: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/PK-Vozdukh-airships-converted.pdf

STRATOSPHERIC AIRSHIPS / HIGH-ALTITUDE PLATFORM STATIONS (HAPS)

- Aerostatica – Stratospheric airship: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Aerostatica-converted.pdf

- Atlas LTA Advanced Technology – Propulsion Assisted High-Altitude Platform (PAHAP): http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Atlas-LTA-Advanced-Technology-airships-converted-compressed.pdf

- Augur RosAeroSystems (RAS) – HAA Berkut: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Augur-RosAeroSystems_R2-converted-compressed.pdf

- Avealto Ltd – HAPS: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Avealto-Ltd_HAPS.pdf

- Beijing Aerospace Technology Co. & BeiHang – Yuanmeng stratospheric airship: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/China_Yuanmeng-stratospheric-airship.pdf

- Capgemini Engineering (formerly Altrans Aerospace) – EcoSat AS30 & AS80: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Capgemini-Engg_Altran-Aerospace-solar-airships-converted.pdf

- CIRA (Italian Aerospace Research Center) – Hybrid High-Altitude Platform Systems (HAPS): https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/CIRA-HAPS.pdf

- ESA / Lindstrand – High-Altitude Long-Endurance (HALE) aerostatic craft: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/ESA_Lindstrand-HALE_R1-converted.pdf

- EU CAPANINA: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/EU-CAPANINA-converted.pdf

- Galileo Systems – Graf Galileo High-Altitude Airship: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Graf-Galileo-High-Altitude-Airship.pdf

- NASA 20-20-20 airship challenge: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/NASA-20-20-20-airship-challenge-converted-1.pdf

- Sanswire / WSGI – Stratellite One & Argus One: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Sanswire-WSGI-airships-converted-compressed.pdf

- Sceye Inc. – stratospheric airship: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Sceye_stratospheric-airship-converted.pdf

- Strasa.Tech – HAPS platform: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Strasa-Tech-converted.pdf

- Stratosyst – Skyrider: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Stratosyst-Skyrider.pdf

- StratXX – X-Station: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/StratXX-airships-converted-1.pdf

- TAO Group – SkyDragon: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/TAO-Group-airships-converted.pdf

- Thales Alenia Space – Stratobus: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Thales-Alenia-Space_Stratobus-converted.pdf

PERSONAL GAS AIRSHIPS

- Airstar – Electroplume 250 & 320, Elliptoplume 150 & Manned AéroLifter:https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Airstar_airships_tethered-aerostat_stratospheric-balloons.pdf

- A-NSE – A-N400: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/A-NSE.pdf

- Project Sol’R – Nephelios: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Project-SolR_Nephelios_R1-converted-1.pdf

- Shi Songbo – personal blimp: Coming in 2024

THERMAL (HOT AIR) AIRSHIPS

- Airstar – Colibri 1800: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Airstar_airships_tethered-aerostat_stratospheric-balloons.pdf

- Augur RosAeroSystems (RAS) – Au-29, -31, -35 & -37: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Augur-RosAeroSystems_R2-converted-compressed.pdf

- Ural OKBD – Thermostat (spindle & lenticular): http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Bimbat-Ural-OKBD-airships-converted.pdf

ELECTRO-KINETICALLY (EK) PROPELLED AIRSHIPS

- Festo – b-IONIC Airfish: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Festo_b-IONIC-Airfish_R1-converted.pdf

- Walden Aerospace / Lighter Than Air Solar (LTAS) – XEM-1, EK-1 & BBD: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Walden-LTAS_EK-propelled-airships.pdf

LTA DRONES

- Aero Drum – Uniblimp drone: Coming in 2024

- Aerotain AG – Skye spherical blimp: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Aerotain_Skye-spherical-drone-converted.pdf

- Airspeed Airships – AS-series drone blimps: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Airspeed-Airships.pdf

- Airstar Aerospace – Airstar Canada – cargo airship drone: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Airstar_airships_tethered-aerostat_stratospheric-balloons.pdf

- BAK – EM50 blimp: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/BAK_EM50-drone-blimp-converted.pdf

- Cloudline – autonomous cargo airship drone: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Cloudline_UAV-cargo-blimp.pdf

- DKBA – conventional airships – drones: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/DKBA-conventional-airships-converted.pdf

- DKBA – lenticular airships – drones: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/DKBA-lenticular-airships-converted.pdf

- Hemeria (formerly CNIM Air Space) – Diridrone: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Hemeria_CNIM-Air-Space-compressed.pdf

- Hipersfera d.o.o. – Hypersphere HS-5K multipurpose drone: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Hypersphere-converted.pdf

- HyLight – blimp drone: Coming in 2024

- India Defense Research and Development Organization (DRDO) ADRDE – drone blimp: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/DRDO-ADRDE-aerostats-small-unmanned-airship.pdf

- Information Technology Institute, Campinas – AURORA semi-autonomous drone blimp: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/AURORA-semi-autonomous-blimp.pdf

- Jülich Institute – FieldShip UAV blimp: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Julich-Institute-FieldShip-UAV-blimp.pdf

- Kelluu Airships – drone blimps: Coming in 2024

- Korea Telcom – KT 5G Skyship drone airship: Coming in 2024

- LAAS / CRNS – Karma semi-autonomous blimp: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Karma-semi-autonomous-blimp.pdf

- Lindstrand Technologies – GA-22 drone blimp: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Lindstrand-GA-42-GA-22-converted.pdf

- Mustafa Demir – drone blimp: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Mustafa-Demir_aerostat-drone-airship-converted.pdf

- Otonom Teknoloji – drone airship: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Otonom-Teknoloji-aerostats-drone-airship.pdf

- Shanghai Jiao Tong University – ZY-1 & Tianzhou-1: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/China_Shanghai-Jiao-Tong-University_Research-airships-1.pdf

- StratXX – PhoexiXX drone: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/StratXX-airships-converted-1.pdf

- Suzhou Ark Aviation Technology Co. Ltd. – drone blimps: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/China_Suzhou-Ark-Aviation-Co.pdf

- TAO Group – Lotte airship: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/TAO-Group-airships-converted.pdf

- Transoceans – Léilo sub-scale demonstrator: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Aerial-Concept-Group-Transoceans-converted.pdf

- Ural OKBD – Ural-4 (MIASS-1) drone: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Bimbat-Ural-OKBD-airships-converted.pdf

- Vantage Airship Manufacturing Co., Ltd. – drone blimps: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Vantage-Airship_R2-converted.pdf

UNPOWERED AEROSTATS

Tethered aerostats (Kite balloons)

- Abu Dhabi Autonomous Systems Investment (ADASI) – aerostats: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/ADASI-aerostats.pdf

- A-NSE – T-C350 & T-C1400 tethered aerostats: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/A-NSE.pdf

- Aero-T – SkyGuard tethered: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Aero-T-SkyGuard.pdf

- Airborne Industries – tethered aerostats aerostats & parachute training balloons: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Airborne-Industries-aerostats.pdf

- Airstar Aerospace – White Hawk, Eagle Owl & Condor tethered aerostats: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Airstar_airships_tethered-aerostat_stratospheric-balloons.pdf

- Atlas LTA Advanced Technology – tethered aerostat & THAP: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Atlas-LTA-Advanced-Technology-airships-converted.pdf

- Augur RosAeroSystems – tethered aerostats: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Augur-RosAeroSystems-tethered-aerostats.pdf

- China Mobile – Cloud One – 5G base station aerostat: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/China_Cloud-One-5G-base-station-aerostat.pdf

- Chinese Academy of Sciences – Jimu No 1 – high-altitude aerostat: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/China_Jimu-No-1-high-altitude-aerostat.pdf

- Hangzhou Gauss Inflatable Tech Co. – inflatable blimps & aerostats: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/China-Gauss-Inflatable-blimps-aerostats.pdf

- Hemeria (formerly CNIM Air Space & Airstar Aerospace) – White Hawk, Eagle Owl & Condor tethered aerostats: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Hemeria_CNIM-Air-Space-compressed.pdf

- India Defense Research and Development Organization (DRDO) ADRDE – aerostats & small unmanned airship: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/DRDO-ADRDE-aerostats-small-unmanned-airship.pdf

- Israel Aerospace Industries (IAI) – HAAS aerostat: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Israel-Aerospace-Industries-HAAS-aerostat.pdf

- Mustafa Demir – tethered aerostat: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Mustafa-Demir_aerostat-drone-airship-converted.pdf

- Otonom Teknoloji – tethered aerostats: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Otonom-Teknoloji-aerostats-drone-airship.pdf

- RT LTA Systems Ltd. – Skystar™ tethered aerostats: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/RT-LTA-Systems-Ltd-aerostats.pdf

- StratXX – X-Tower tethered aerostat: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/StratXX-airships-converted-1.pdf

- Suzhou Ark Aviation Technology Co. Ltd. – aerostats: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/China_Suzhou-Ark-Aviation-Co.pdf

Tethered manned aerostats

- Aerophile SAS – sightseeing balloons: Coming in 2024

- Airborne Industries – tethered aerostats aerostats & parachute training balloons: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Airborne-Industries-aerostats.pdf

- Atlas LTA Advanced Technology – Skylift sightseeing aerostat: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Atlas-LTA-Advanced-Technology-airships-converted.pdf

- Augur RosAeroSystems – AL-30 sightseeing aerostats: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Augur-RosAeroSystems-tethered-aerostats.pdf

- Lindstrand Technologies – HyFlyer, SkyFlyer sightseeing balloons & Gen2 parachute training balloons: Coming in 2024

Tethered LTA wind turbines

- Aeerstatica Energy Airships: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Aeerstatica.pdf

- AirbineTM Renewable Energy Systems (ARES) – Airborne Wind Turbine (AWT): https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Airbine-AWT.pdf

- Altaeros Energies – Buoyant Airborne Turbine (BAT): Coming in 2024

- LTA Windpower Inc. – PowerShip: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/LTA-Windpower-Inc.pdf

- Magenn Air Rotor System – MARS: Coming in 2024

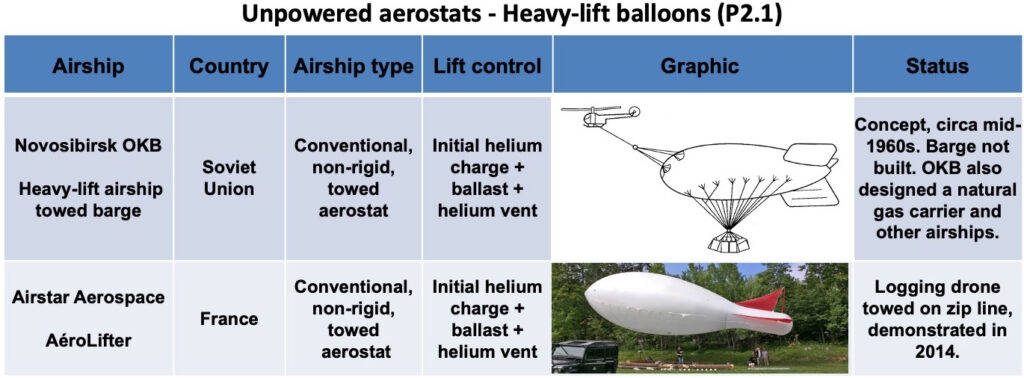

Tethered heavy lift balloons

- Airstar Aerospace – AéroLifter: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Airstar_airships_tethered-aerostat_stratospheric-balloons.pdf

- Novosibirsk OKB – Heavy-lift airship towed barge: http://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Novosibirsk-OKB-airships-converted.pdf

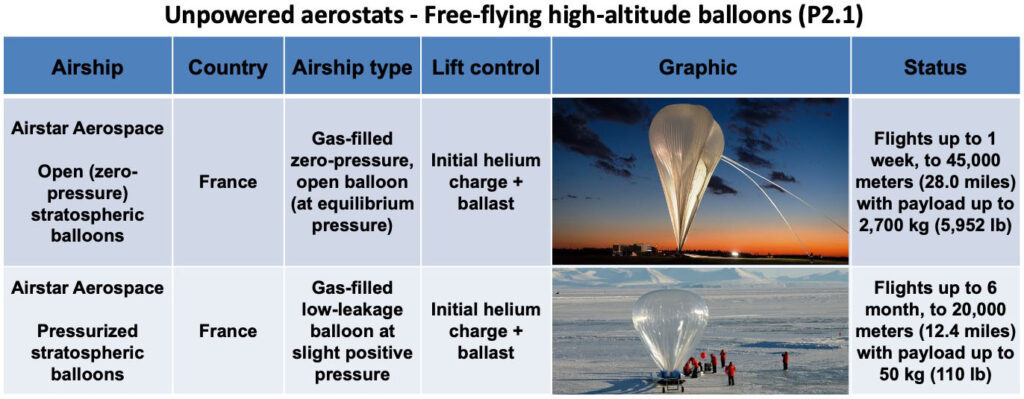

Free-flying high-altitude balloons

- Airstar Aerospace – stratospheric balloons: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Airstar_airships_tethered-aerostat_stratospheric-balloons.pdf