We are driving through Kachchh, speeding away towards the east.

Today we are going to Bela, a village en route to Dholavira, the historic site of the Indus Valley Civilization. We are in the district of Rapar and I can already see the Rann.

“Shruthi, do you know about the people that live here?”

“Hmm?”

“They do not think twice about picking a fight, and even less before picking up a weapon!”

“Yes, yes, he is right. They are a very fighter type, you should be careful!”

I am warned about rubbing against people on the streets when we get off the car.

I don’t know what to say.

“Arey, it is a joke yaar. Relax!”

Ah.

The other two in the car are nearly snoring.

We started at 6am, it is nearly 9 now.

Bela is a village about 30kms away from Rapar. It is believed to have been very close to the sea once upon a time. The land eventually rose above sea level. Bela used to be a flourishing village for blockprint. That is also why we are here today.

“Have we reached?”

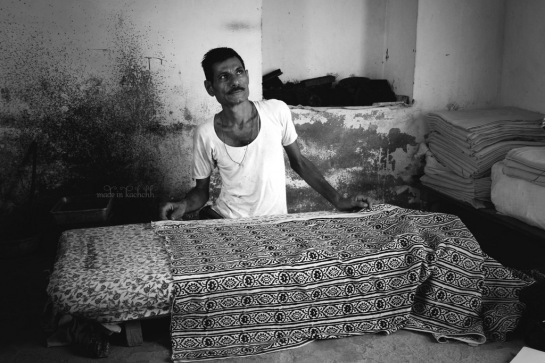

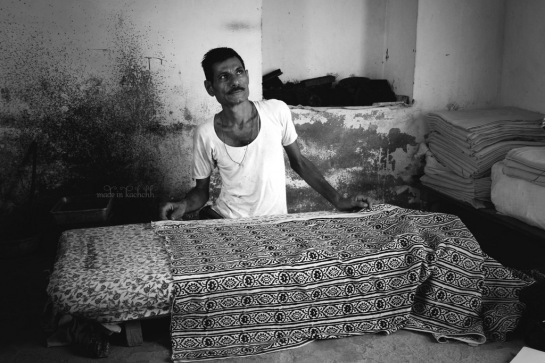

We enter the front room of a house, with a high ceiling. The fan is running at full speed with an unusual hum. The only other noise is the rhythmic thumping of wooden blocks against the thick cotton canvas cloth. There are two low wooden tables on either side of the room. Behind one of them sits Mansukh, with his old tiny blocks and the ubiquitous yellow canvas.

Mansukh is a Hindu Khatri.He is also the last blockprinter left in Bela.

Bela is an old town, maybe 300 years old, once ruled by Rao of Kachchh. The town today has about 200 families living there. They mostly do farming. Some of them have kept shops. The market space is closed during most of the time that we are in the village.

“They are sleeping. Shop will open when sleep leaves town”, says Mansukh.

He prints designs for bags, given to him on order by some businessmen(shops) in Bhuj. He has been printing the same thing ever since he learnt the craft and started off on his own. He also prints designs for cushion covers, the patterns of which are decided by the businessmen.

Mansukh works alone. He prints and dyes by himself. He still uses the same blocks from his grandfather’s times. No new blocks have been made since two generations. The blocks are really tiny compared to the ones I have seen in Ajrakhpur or Dhamadka.

Since they are half the size as compared to the new ones used by blockprinters today, Mansukh takes twice the time to print a unit metre of cloth.

Once he finishes an order, he travels to Bhuj with it. At the store he is made to check and count every metre of cloth in front of the businessmen who makes sure his calculations are correct. He receives Rs15 per bag!

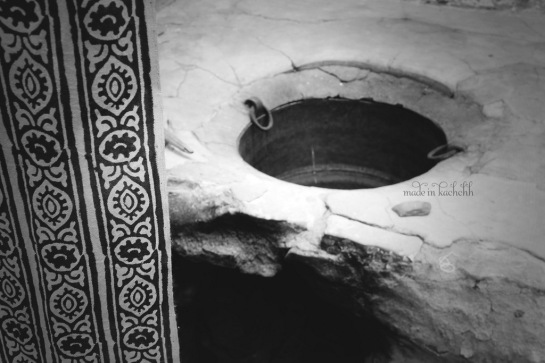

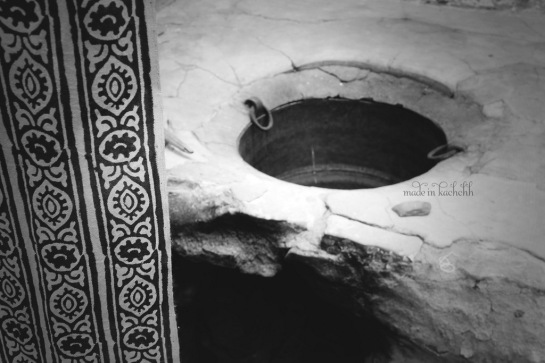

The front room leads into the courtyard of their house. It is here that the dyeing is done. I notice that the vessel used for dyeing is of old style with a narrow bottom, one that I had seen the previous day in an antique collectors shop. When was the last time he used it?

Drinking water is an issue in the town. A tanker fills the private tanks of people once every two days. For dyeing purposes, they had a canal earlier whose water was very kaadak(hard/salty), that dried up. So now he has to collect water from a bore well, a little further away.

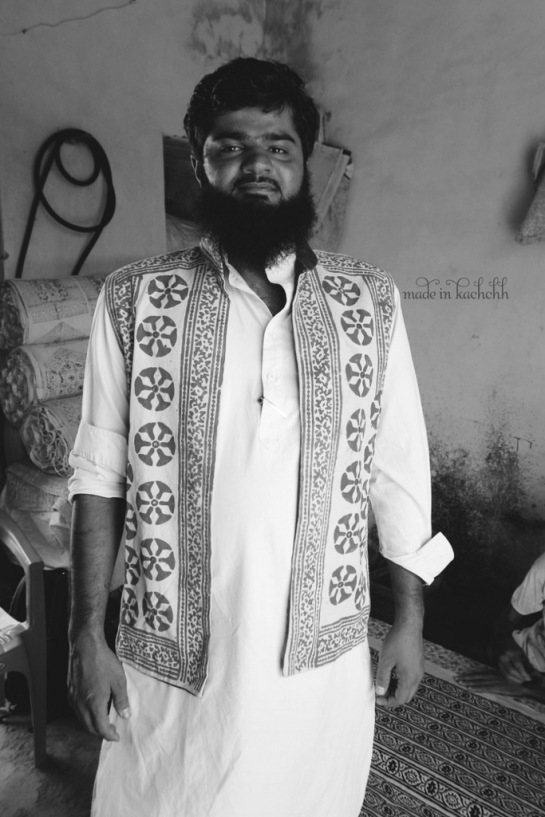

“In Ajrakhpur, we are so lucky!” says Rauf. “We use sooo much water, sweet water!”

Beyond the courtyard lies the family home. The house was completely reconstructed after the earthquake, using the old wood and stone. It is charming even today. He has 3 children. The oldest one is working in Bhuj while the younger daughter and son stay with their parents in Bela.

None of his children want to follow their father’s footsteps.

Mansukh learnt the craft from his brother. His father died 40 years ago.

“How old are you now Mansukhbhai?” I ask him.

“I must be 50.”

His brother now keeps a sweet shop.

After the India Pakistan separation, the people started leaving the village of Bela for newer prospects in larger towns. They moved to Ahmedabad and even Mumbai. The town hence lost its visitors and slowly the only remaining people settled down to having petty groceries, milk and sweet shops besides agriculture. There used to be atleast 60 blockprinters in Bela. They have all closed.

“Why did you not leave?” I ask.

“I do not know anything else. This is what I do.”

“Yes, he had stopped in-between for a while, but he got back”, says his daughter.

She seems like a very clever child. His son is shy and has lost complete hope in his father’s work. He does not believe it is a ‘valuable’ thing to do. He is the youngest kid, probably 12 years old. Cannot blame him. We discuss about how a ‘blockprinting man’ will not find a wife now in Bela. It may be best for his son not to take over.

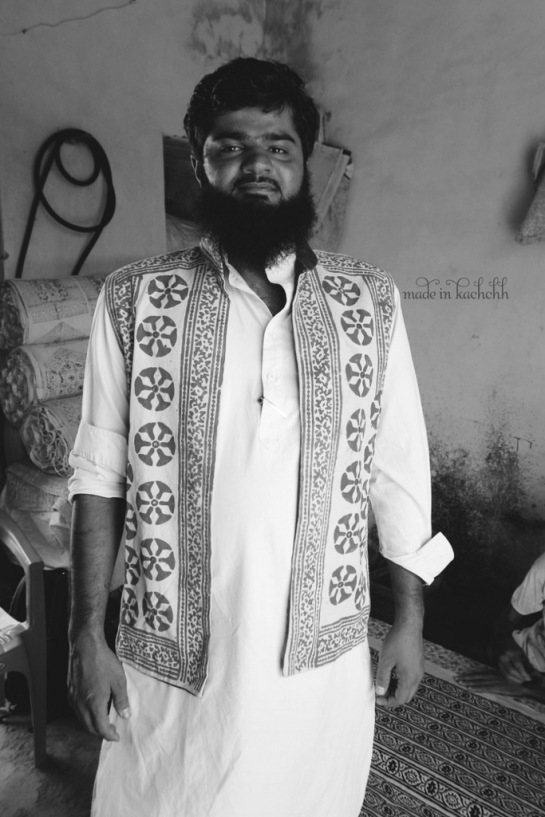

Mansukh shows us all the traditional blocks and some scrap pieces of old blockprinted fabric that he has. We speak about designs and take photographs. He even shows us a jacket that he had designed, but that was a while ago.

They offer us lunch. Delicious potato sag with tiny tiny pooris (just like his blocks), and sevaiyya (sweet) and chaas (buttermilk).

Mansukh is a man of few words. I cannot say if his silence is from wisdom or from lack of exposure. He is very isolated from the rest of the blockprint community of kachchh. He has a kind of naive curiosity about Ajrakhpur after lunch, “What do you make there?” he asks Rauf. Is it a question coming from a man stuck in the past?

“Come to Ajrakhpur and see. Sarees, dresses, stoles, bedspreads, you name it and we make it there!” says Rauf. Mansukh smiles, do I see a hint of hope?

We speak a lot to Mansukh’s son, Rauf tells him about how successful his business is in Ajrakhpur.

No reaction.

How blockprinting is done in several different ways and products.

No reaction.

How he gets to travel a lot.

No reaction.

How many foreigners visit his house everyday.

“Oh really!?”, comes the response. We show him pictures of Rauf’s workshop on madeinkachchh blog.

We hope they will visit Ajrakhpur.

When we are about to leave and start our byes, Mansukh says, “We had many more blocks. Traditional ones. But my brother and I had no use for them. We packed them up in a sack and dropped them into the river.”

Oh.

*********

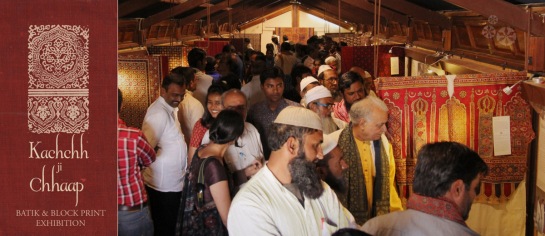

Together with the Printers and Dyers of Kachchh

– The Blockprint Collective – an exhibition coming soon in December 2013 at Khamir