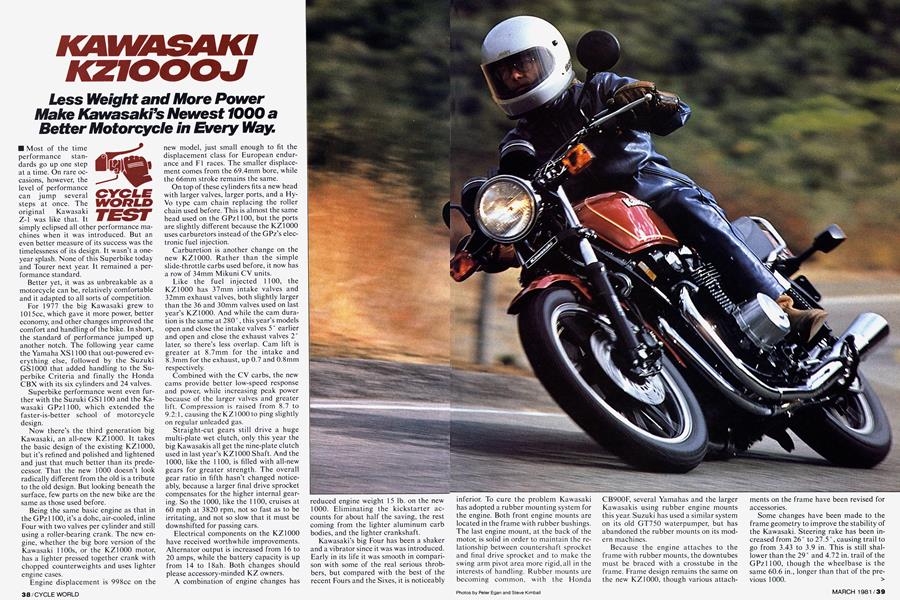

KAWASAKI KZ1000J

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Less Weight and More Power Make Kawasaki's Newest 1000 a Better Motorcycle in Every Way.

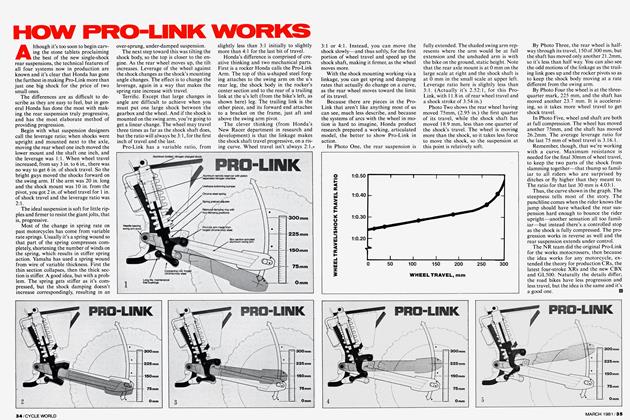

Most of the time performance standards go up one step at a time. On rare occasions, however, the level of performance can jump several steps at once. The original Kawasaki Z-1 was like that. It simply eclipsed all other performance machines when it was introduced. But an even better measure of its success was the timelessness of its design. It wasn't a oneyear splash. None of this Superbike today and Tourer next year. It remained a performance standard.

Better yet, it was as unbreakable as a motorcycle can be, relatively comfortable and it adapted to all sorts of competition.

For 1977 the big Kawasaki grew to 1015cc, which gave it more power, better economy, and other changes improved the comfort and handling of the bike. In short, the standard of performance jumped up another notch. The following year came the Yamaha XS1100 that out-powered everything else, followed by the Suzuki GS1000 that added handling to the Superbike Criteria and finally the Honda CBX with its six cylinders and 24 valves.

Superbike performance went even further with the Suzuki GS1100 and the Kawasaki GPzl 100, which extended the faster-is-better school of motorcycle design.

Now there's the third generation big Kawasaki, an all-new KZ1000. It takes the basic design of the existing KZ1000, but it's refined and polished and lightened and just that much better than its predecessor. That the new 1000 doesn't look radically different from the old is a tribute to the old design. But looking beneath the surface, few parts on the new bike are the same as those used before.

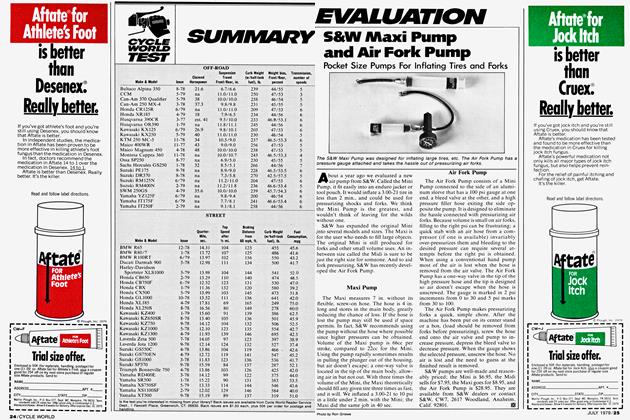

Being the same basic engine as that in the GPzl 100, it's a dohc, air-cooled, inline Four with two valves per cylinder and still using a roller-bearing crank. The new engine, whether the big bore version of the Kawasaki 1100s, or the KZ1000 motor, has a lighter pressed together crank with chopped counterweights and uses lighter engine cases.

Engine displacement is 998cc on the

new model, just small enough to fit the displacement class for European endurance and FI races. The smaller displacement comes from the 69.4mm bore, while the 66mm stroke remains the same.

On top of these cylinders fits a new head with larger valves, larger ports, and a HyVo type cam chain replacing the roller chain used before. This is almost the same head used on the GPzl 100, but the ports are slightly different because the KZ1000 uses carburetors instead of the GPz's electronic fuel injection.

Carburetion is another change on the new KZ1000. Rather than the simple slide-throttle carbs used before, it now has a row of 34mm Mikuni CV units.

Like the fuel injected 1100, the KZ1000 has 37mm intake valves and 32mm exhaust valves, both slightly larger than the 36 and 30mm valves used on last year's KZ1000. And while the cam duration is the same at 280 °, this year's models open and close the intake valves 5 ° earlier and open and close the exhaust valves 2° later, so there's less overlap. Cam lift is greater at 8.7mm for the intake and 8.3mm for the exhaust, up 0.7 and 0.8mm respectively.

Combined with the CV carbs, the new cams provide better low-speed response and power, while increasing peak power because of the larger valves and greater lift. Compression is raised from 8.7 to 9.2:1, causing the KZ 1000 to ping slightly on regular unleaded gas.

Straight-cut gears still drive a huge multi-plate wet clutch, only this year the big Kawasakis all get the nine-plate clutch used in last year's KZ1000 Shaft. And the 1000, like the 1100, is filled with all-new gears for greater strength. The overall gear ratio in fifth hasn't changed noticeably, because a larger final drive sprocket compensates for the higher internal gearing. So the 1000, like the 1100, cruises at 60 mph at 3820 rpm, not so fast as to be irritating, and not so slow that it must be downshifted for passing cars.

Electrical components on the KZ1000 have received worthwhile improvements. Alternator output is increased from 16 to 20 amps, while the battery capacity is up from 14 to 18ah. Both changes should please accessory-minded KZ owners.

A combination of engine changes has reduced engine weight 15 lb. on the new 1000. Eliminating the kickstarter accounts for about half the saving, the rest coming from the lighter aluminum carb bodies, and the lighter crankshaft. Kawasaki's big Four has been a shaker and a vibrator since it was was introduced. Early in its life it was smooth in comparison with some of the real serious throbbers, but compared with the best of the recent Fours and the Sixes, it is noticeably inferior. To cure the problem Kawasaki has adopted a rubber mounting system for the engine. Both front engine mounts are located in the frame with rubber bushings. The last engine mount, at the back of the motor, is solid in order to maintain the relationship between countershaft sprocket and final drive sprocket and to make the swing arm pivot area more rigid, all in the interests of handling. Rubber mounts are becoming common, with the Honda

CB900F, several Yamahas and the larger Kawasakis using rubber engine mounts this year. Suzuki has used a similar system on its old GT750 waterpumper, but has abandoned the rubber mounts on its modern machines.

Because the engine attaches to the frame with rubber mounts, the downtubes must be braced with a crosstube in the frame. Frame design remains the same on the new KZ1000, though various attachments on the frame have been revised for accessories.

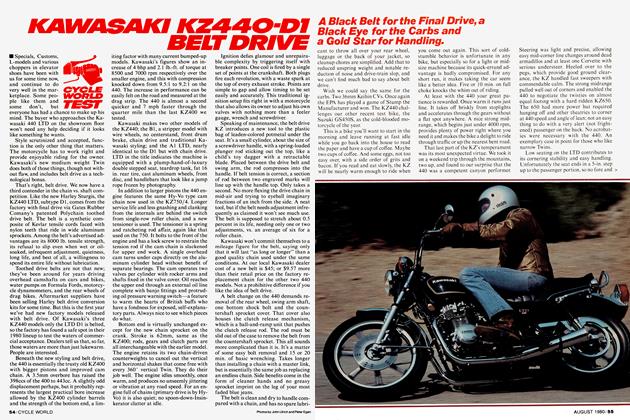

Some changes have been made to the frame geometry to improve the stability of the Kawasaki. Steering rake has been increased from 26 ° to 27.5 °, causing trail to go from 3.43 to 3.9 in. This is still shallower than the 29° and 4.72 in. trail of the GPzllOO, though the wheelbase is the same 60.6 in., longer than that of the previous 1000.

Suspension components have undergone the same kind of careful re-think as the engine. The forks have more travel this year, 5.7 in., with softer springs and greater preload. Rebound springs are now included in the forks. Air caps assist the coil springs. Damping remains the same. Rear springs are 24 percent stiffer, use the same 3 in. stroke and come with five-position adjustable damping. The damping rates can be both lighter and heavier than the single-rate dampers fitted to previous KZ 1000s. Damping is easily adjusted by rotating the collar surrounding the top of the springs.

Like the other motorcycle manufacturers, Kawasaki has added a large number of features to the KZ1000. While most of the so-called features introduced each year are of questionable value, the Kawasaki's collection is indeed impressive. The seat, for instance, uses two densities of foam so it can have the proper firmness where it should. The dual horns are no longer a joke, being louder than some automotive horns. A number of small pegs are welded to the frame as bungee cord attachments. Other frame attachments are welded on for fairing mounts, or engine case guards, and there's even a receptacle for a locking cable. The electric speedometer and tachometer eliminate cables running to the instruments and are highly accurate. Hand grips are softer and so is the throttle return spring. The fuse panel includes an accessory terminal and is hidden under the seat as an anti-hotwire system.

One feature a rider might never think about or see is the emission system Kawasaki uses on most all its larger motorcycles. It's an air suction system that allows fresh air to be injected into the exhaust ports, causing the exhaust to be oxidized, and reducing carbon monoxide and hydrocarbons. It's a simple, no-maintenance system that enables Kawasaki to jet the carburetors for peak performance, not extra-lean emissions.

Styling hasn't been overlooked on the KZ1000, even though this isn't an LTD. The tank is a gracefully shaped piece that's also reasonably sized at 5.6 gal. The sidecovers are neat and clean and the upswept tailpiece just hints at the original Z-l. Again, there are little touches adding to the appearance. The bottom triple clamp has a shiny black enameled surface. The round gauges incorporating the warning lights are far more attractive to us than the breadbox used on the GPz.

Following the trend of the recently introduced KZ550 and KZ750, the new 1000 is noticeably lighter than its competition. At 535 lb., the KZ1000J weighs a little less than most of the other guys' 750s. The Honda CB750F, for instance, weighs in at 540 lb. and the Suzuki GS750 weighs 550 lb. (The last GS1000E weighed 550 lb., but it's no longer produced, replaced by the GS1100 and GS1000G shaft drive.)

All the lightweight pieces, the light cast wheels and small brake rotors and plastic seat pan and others make the KZ1000 feel more like a 750, even though the bike is big, with a 60.6 in. wheelbase. Such light weight is the key to the bike's excellent handling and speed. And it has lots of handling and speed.

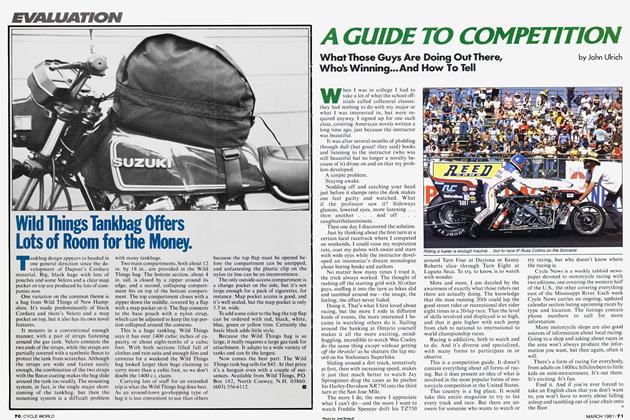

This is the fastest lOOOcc Four we've

tested, reaching a speed of 134 mph in our half-mile test and running through the quarter mile in 11.56 sec. at 115.53 mph. The only two stock bikes quicker are the GS1100 Suzuki and the GPz 1100. And the KZ 1000 is as close to the Suzuki as the Suzuki is to the GPz in quarter mile times.

Just because a pair of 1100s can accelerate a trifle harder, don't think the KZ1000 can be left behind when the riders get serious. The 1000's weight advantage gives it a couple of aces up its sleeve in handling and braking, and the steering geometry takes full advantage of the benefits.

Even without the rear-set pegs of the GPz, the KZ1000 has well tucked in pipes and controls. In racetrack use, when the stands are removed, the engine cases will limit cornering clearance on any of the fast machines. But the 1000 Kawasaki has even lighter, more positive handling than

the GPz, enabling it to turn under the larger Kawasaki in a corner. The steering precision is more like that of Kawasaki's KZ750, though less sensitive. It has the kind of handling that can make a 750 more enjoyable to ride than a 1000, though in this case the 1000 feels that way.

Other bikes have had steep steering head angles and short trail, making them faster turning but less stable. The Kawasaki is different. The wheelbase is long and the steering head is only moderately steep. What gives the KZ1000 its exemplary handling are the larger 38mm stanchion tubes and the extra-wide 9.5 in. spacing of the triple clamps. Not since the short travel suspensions on some of the European motorcycles has there been such a direct feel between the handlebars and the front wheel of a motorcycle. The difference is particularly noticeable when the KZ is compared with a Suzuki GS1 100. Put them both on a centerstand and jerk the handlebars and the GS will respond with a rubbery feel. The Kawasaki has no flex. Hit the handlebars and the front wheel is instantly moved. On the road the same reactions occur. Push on the Kawasaki's bars and the wheel instantly responds, making fast direction changes even faster.

As a sport motorcycle, the 1000's lighter weight and quicker steering make it more fun than the larger 1100s, even though it doesn't have quite the same brute power. Even the greatest horsepower monger in the office preferred the 1000 to the 1100 as an all-around sport bike.

Part of the 1000's appeal comes from its comfortable seating position. Kawasaki has wisely left the six-foot long handlebars for the LTD and CSR versions, so the J-model gets comfortable trim handlebars. Actually Kawasaki has been putting on the best fitting standard handlebars on its motorcycles in the last couple of years. The position doesn't force a rider to lean back or forward too far and pleases the greatest number of riders on the staff. The seat, for its part, is good, but not outstanding. The shape is fine and the dual density foam padding works well for most people, but on a long ride it could be softer.

Vibration control on the KZ1000 is an improvement over the previous Kawasaki 1000s, but there's plenty of room for improvement. As on the GPz, at the common 60 to 65 mph cruising speed lots of buzzing comes through the gas tank. The pegs and bars transmit less vibration on the 1000, but it's certainly noticeable. At higher engine speeds everything smooths out. Even if rider comfort isn't substantially improved the rubber engine mounts may be doing their job by reducing vibration in the frame.

What the rider hears from the bike depends on what speed he's riding. Like in the previous 1000 Four,the straight cut primary gears make a loud whine at low speeds, particularly when decelerating. At idle the Kawasaki's exhaust system produces a noticeable rumbling sound. It's deep, louder than many of the strangledsounding machines produced lately, and it's a wonderful sound. At cruising speed or faster only wind noise can be heard on the bare bike, although the primary gear noise might be heard if a fairing were installed.

All those ancillary pieces that make motorcycles legal are conveniently situated and work well, for the most part. The halogen headlight is bright and well defined. The turn signals don't come with a self-canceller. The gas gauge is prone to moving too fast during the last half of the tank because it didn't move at all during the first half. At least there's a reserve on the vacuum-operated petcock. A push button returns the trip odometer to zero, but the standard odometer can't be read while underway because of the angle of view from the riding position. Clutch pull is firm but not excessive, the lighter throttle return spring is much appreciated and the softer grips are certainly a step in the right direction. The emergency flasher button is so convenient a rider can easily hit it when trying to change headlight beams, which can be annoying. Shifting takes considerable effort, but missed shifts are rare.

Braking performance and control on this model were very good. Except for the brake pads, the brake parts on the 1000 were the same as those on the GPz prototype that were excessively powerful, so apparently Kawasaki has found the cure. Braking distances were good: 36 ft. from 30 mph and 137 ft. from 60 mph with no locking. And the suspension worked better on this bike during braking, keeping both wheels on the ground throughout the tests.

Maintenance on big multi-cylinder motorcycles, according to many people who've never owned one, can be something of a problem. But the Kawasaki should continue to be a very low maintenance machine. With its electronic ignition there are no points to adjust or clean or replace. The silent cam chain has an automatic chain tensioner. The four carbs are mounted together and operated by a common linkage, alleviating any serious synchronization problems. Admittedly the shim-type valve adjustment can't be done with just a wrench and screwdriver and feeler gauge. To its credit, the shim adjusting system generally holds adjustment longer than screw-adjust rocker arms, and there's no rocker arm shaft or bearings to wear out. Also, the KZ1000 has its adjusting shims located on top of the cam follower so the cams don't have to be removed to adjust the valves. In short, the KZ1000 shouldn't take any more time for maintenance over the years than any other bike made.

As an all-around large displacement machine, the new KZ1000 is a tremendous package. It's fast, comfortable, good handling, easy to ride and has no serious shortcomings. Surrounded in Kawasaki's lineup by the more powerful GPzllOO, the more comfortable KZI 100 Shaft, the high-zoot LTD and CSR models, the standard 1000 doesn't need to sacrifice anything in the interests of specialization.

Like many of the other recently introduced Kawasakis, the 1000 has its own identifiable character. This is not another big four cylinder machine just like so many that have gone before. Its level of performance, the precision of its handling, and that distinct Kawasaki hardness of form would enable any rider to know this is a Kawasaki, even if he could ride the bike blindfolded.

No one doubted that the new KZ1000 would be a better all-around motorcycle than the fast-first GPzl 100, but it was a surprise that the 1000 was more satisfying for sport riding, too. Once again Kawasaki has shown us that bigger isn't always better.

KAWASAKI KZ1000J