Introduction [Both]

Pregnancy and childbirth are major processes in every culture, however, there are cultural differences to be examined. The Inuit are of special consideration in this regard as they make up a significant portion of the Northern Canadian population. Traditional Inuit practices have been challenged in recent decades by influence and pressure from the Canadian government and western biomedical approaches. Although it appeared that indigenous Inuit customs and biomedicine could not work in collaboration with one another, there is evidence to support that these opposing systems can work in harmony.

Inuit – The Indigenous People of Canada’s Arctic [Kirstie]

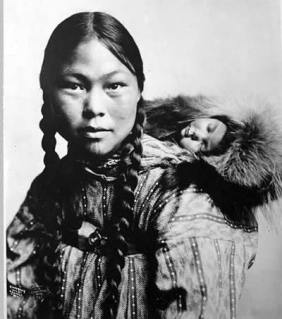

The Inuit are an Aboriginal culture, inhabiting the high arctic of Canada (Douglas, 2013). Due to living within a harsh environment, the Inuit way of living focused heavily on survival and group cooperation (Douglas, 2013). As of the 2006 census, there were 50,000 Inuit people within Canada (Douglas, 2013). Their culture forms the majority within Nunavut and comprises a significant portion of the population in the Northwest Territories, Northern Quebec, and Northern Labrador (Douglas, 2013). They are distinct from southern First Nations groups, though they share strikingly similar world views (Douglas, 2013). The traditional knowledge of the Inuit supported a society in which people are connected with nature and are viewed as a vital part of the ecological system (Douglas, 2009). Their belief system incorporated human, natural, and supernatural components (Douglas, 2009). This is, of course, radically different from Western epistemology (Douglas, 2013). Modern westernized beliefs separate culture and nature in an attempt to understand and manipulate natural processes through the use of science (Douglas, 2009). Rather than humans being viewed as a part of the ecosystem, they are seen as external to nature with the ability to physically alter it to one’s benefit (Douglas, 2009). It is clear, through examination of these philosophies, that the two systems would have difficulty operating together successfully. The struggles faced while accommodating for cultural differences can be demonstrated through exploring the relationship of Western biomedicine to Inuit pregnancy and birthing.

Inuit Traditional Beliefs and Practices Surrounding Pregnancy and Childbirth [Both]

Examining the traditional beliefs and practices surrounding pregnancy and childbirth within the Inuit culture reveals a unique set of customs. In order to understand the impact of western biomedicine, we must first acknowledge the way in which the Inuit historically viewed pregnancy and childbirth. Inuit world view encompasses a close connection to nature and the spirit world that extends to their prenatal and birthing practices (Douglas, 2010). For example, a shaman would likely be contacted in the event of miscarriage or if spiritual interference was suspected (Douglas, 2006; Douglas, 2010). There were no “doctors” involved – shamans were the closest equivalent (Douglas, 2006). Inuit women also believed that hard work, good virtue, respect for elders, and proper diet would ensure quick and easy labour and produce a healthy child, so pregnant women followed this type of regimen (Kaufert & O’Neil, 1990). Eating traditional foods such as seal and caribou were part of that regimen and were viewed as important to a pregnant woman’s sense of well-being (Douglas, 2006). Disobeying these rules throughout pregnancy threatened a lengthy and painful labour (Kaufert & O’Neil, 1990). While in modern western society, conceiving out of wedlock is stigmatized, Inuit traditional values did not shame conceiving out of wedlock; in fact, this made a woman more desirable for her fertility (Billson & Mancini, 2007). Teenage pregnancies were not uncommon and were not seen as a negative event (Healey & Meadows, 2008). As a result of the lack of stigma and use of customary adoption, there was no effort to deter women from conceiving as a teenager (Healey & Meadows, 2008). However, in any circumstance that a mother did not want to keep her child, customary adoption typically took place (Billson & Mancini, 2007). A family member such as an aunt, uncle, or grandparents would adopt the child and this was seen as a positive tradition within Inuit communities (Healey & Meadows, 2008). However, if the mother wanted to keep the baby, that decision was supported as well (Billson & Mancini, 2007).

Midwives traditionally and currently play a pivotal role in preparing an Inuit woman and her family for childbirth (Douglas, 2010). Knowledge possessed by midwives was typically passed down generationally and most women had some degree of knowledge in respect to being a midwife (Kaufert & O’Neil, 1990). Emphasis was not necessarily placed on specific techniques such as the position of the mother during labour but rather on assisting her in terms of her own preferences (Douglas, 2010). Inuit women always regarded each birth as a unique experience (Kaufert & O’Neil, 2006). Additionally, midwives focused their attention first on the mother’s life, as they believed that she could bear another child but could not be replaced herself (Billson & Mancini, 2007). After attending the birth, the midwife would continue to be involved in the child’s life (Pauktuutit Suvaguuq, 1995). Children were taught to respect these women as they brought them into the world; for example, they often gave their midwives the first animal they hunted (Pauktuutit Suvaguuq, 1995). A traditional attendant, called a sanaji or sanariuk, would also be present to cut the infant’s umbilical cord and become involved in the child’s life; this was usually distinct from the midwife but a midwife could also adopt this role (Douglas, 2006). The detached stump of the umbilical cord was traditionally preserved by wrapping it in leather to ensure that the child would never feel something was missing (O’Driscoll et al., 2011). After the child was born, he or she would also be wrapped in a traditional cradleboard called a tikinagan which was believed to secure the baby, resembling the comfort of the mother’s womb (O’Driscoll et al., 2011). Although many individuals were customarily present for the birth, these were optimal circumstances and in some cases, the mother would have only her husband or have to manage birthing alone (Douglas, 2006). This happened often when the birth would occur in transit or while in hunting camps (Douglas, 2006). Courage and concentration during labour were highly esteemed, especially if a woman gave birth without assistance (Kaufert & O’Neil, 1990). Crying was discouraged throughout labour – women were expected to keep their composure (Kaufert & O’Neil, 1990). Decisions regarding childbirth were made by consensus among community members, with particular weight given to knowledge provided by elders (Douglas, 2010). However, no hierarchy existed in Inuit communities, therefore decisions were not made without complete consensus and elders were not given ultimate authority (Douglas, 2010). There were few large settlements so a larger social support network was provided through camps (Douglas, 2010). These camps were set up for pregnant women to visit and receive assistance throughout their pregnancy, though they were not restricted to this purpose (Douglas, 2010). It is important to note that the Inuit did not see childbirth as a pathological process, though they did acknowledge that complications could occur (Kaufert & O’Neil, 1990). Inuit women expressed fear of postpartum hemorrhage and breech deliveries; they were prepared with certain skills to deal with these complications (Kaufert & O’Neil, 1990). Evidence supports that prior to European contact, the Inuit people had a low infant mortality rate as they had not been exposed to the contagious disease (Douglas, 2010). They also breastfed, sometimes until their children were over the age of two, which naturally controlled population growth (Douglas, 2010).

Evidently, pregnancy and childbirth within Inuit culture involves a great deal of community support and is highly influenced by their cultural world view. It is apparent that the Inuit historically held a rich set of values that was crucial to their way of life-extending into their prenatal and birthing practices. Examining these traditions provides us with a basis for understanding the impact of the introduction of biomedicine.

The Medicalization of Pregnancy and Childbirth [Kirstie]

The Medicalization of Pregnancy and Childbirth in Canada

In Canada, 99% of childbirths take place in a hospital, 22.5% being caesarian sections (Parry, 2008). This is the direct result of the hospital gaining status as the safest and most appropriate place to deliver a child, resulting in a decline in the use of midwifery (Cahill, 2001). Though midwives were previously the authority for the means of childbirth, they were effectively replaced by modern medicine around 1950 (Parry, 2008). Remarkably, no real supporting research or evaluation occurred in the course of this transition (Cahill, 2001). This process was partially forceful from a profession controlled by men, however, women were also convinced that transition to biomedicine may be beneficial (Parry, 2008). By the 1970s, women were dissatisfied with the change which lead to an attempted resurgence in midwifery (Parry, 2008). The Canadian system did not, however, provide the appropriate conditions for midwifery to thrive as it should have, with limited medical insurance, a low birth rate, and a large amount of trained medical staff (Parry, 2008). Even when advocating for a return to community-based births, individuals still encountered the problem in a classification of high-risk (Cahill, 2001). Identification of high-risk births is entirely subjective and completed through medical care, often resulting in an unnecessarily large amount of pregnancies obtaining high-risk status (Cahill, 2001). Furthermore, administrating the power to define abnormalities to obstetricians effectively increases their power (Cahill, 2001). Biomedicine has successfully categorized pregnancy as pathological as opposed to a natural process, thus justifying the need for medical intervention (Parry, 2008). As a result, pregnant women are treated as though they are in need of constant monitoring and intervention due to apparent risks to the fetus and mother (Parry, 2008). As soon as a woman discovers she is pregnant, the medical system views her no longer as an individual but as a vehicle for a child (Parry, 2008). Women are also often perceived and treated as though they are deficient in the required knowledge to manage their pregnancy independently (Parry, 2008). A historical examination provides an understanding of the ultimate authority placed in the hands of medicine (Cahill, 2001). As physicians, surgeons, and apothecaries formed themselves as “doctors”, they were able to dismiss and discredit others such as midwives (Cahill, 2001). These formalized groups came prepared with “scientific” knowledge and a strong stance against abortion, therefore asserting their dominance through intellectual and moral superiority (Cahill, 2001). As a result, biomedical authority triumphed over female intuition, care, and empathy and successfully did so in a sex-divided society (Cahill, 2001). They also completed this shift at a time when perinatal and maternal mortality rates were much higher than they are today (Cahill, 2001). There was a strong assertion that the transition to medicine would alleviate some of these issues (Cahill, 2001). North American privilege that was ultimately given to biomedical understanding fosters an environment where doctors have ultimate authority and are trusted over the mother or other individuals, despite any tangible proof (Parry, 2008). It was and still is a common assumption that birthing in the hospital is the safest option (Cahill, 2001). Midwifery can be, however, viewed as a challenge to this concept of medicalization as it opposes medical birth (Parry, 2008). When Canadian women who had opted to utilize midwives were asked about the medicalization of pregnancy, they stated that it was “so systemic that it’s not even questioned” (Parry, 2008, p. 794). In fact, it seems the entire reproductive cycle of women has become a medical territory. Even women’s hormonal variances are given medical terms such as pre-menstrual syndrome (PMS) or menopause (Cahill, 2001). In addition, the invention of the birth control pill resulted in further medicalization (Tone, 2012). Though it was initially believed that women would reject the idea of daily pills, the birth control pill became a revolutionary success (Tone, 2012). Two years after the birth control pill was approved, it was being used by 1.2 million women and by five years, that figure expanded to over 6 million (Tone, 2012). The ground-breaking contraceptive was awarded the moniker “the pill” (Tone, 2012). Prior to 1960, birth control was not of medical concern and more of a medical focus was placed on childbirth (Tone, 2012). This is a testament to biomedicine’s increasing desire for control over processes or functions that were historically viewed as normal, not pathological – therefore not requiring medical intervention. As a consequence of the pill’s skyrocketing popularity, even further medicalization occurred – the invention increased rates of sexually transmitted infections due to the regularity of unprotected sexual encounters (Tone, 2012). Use of the pill also warrants frequent medical check-ups including breast exams and pap smears, making female reproduction even further entrenched in the medical system (Tone, 2012). With the invention of the home pregnancy test, the process was somewhat demedicalized with discrete, at-home testing (Tone, 2012). However, if a woman tested positive, this only further encouraged her to seek medical care and in the case that she tested negative, a woman may then seek medical care regarding fertilization (Tone, 2012). Medicine altered where women gave birth, who was involved, perspectives regarding the process – essentially every stage of a woman’s reproductive function became involved in biomedicine (Tone, 2012).

The Implications for Inuit Culture

The medicalization of pregnancy and childbirth undoubtedly had a direct impact on Inuit tradition. As mentioned above, the medicalization of pregnancy and childbirth occurred at a time when maternal and infant mortality rates were much higher than they are today (Cahill, 2001). As a result of these safety concerns and direct efforts to assume control, biomedicine dominated over midwifery – a tradition that was greatly valued in Inuit culture (Cahill, 2001; Douglas, 2006). The high infant mortality rates among the Inuit population are attributed to increased government “awareness” of the Inuit women, leading to the assertiveness of their power over Inuit births (Kaufert & O’Neil, 1990). In response, biomedical models were implemented in Inuit settlements through government-built nursing stations in 1960 (Douglas, 2009). This is when it is believed that the full extent of medicalization began within their culture, coinciding with the resurrection of these nursing stations (Kaufert & O’Neil, 1990). Increasing concerns regarding Inuit perinatal and infant mortality eventually lead to the evacuation of births to distant hospitals (Douglas, 2006). Determining which births could occur within Inuit communities was designated by the Department of Health and Welfare in Canada, meaning that the woman, her family, or anyone else in her community had no say in the matter (Kaufert & O’Neil, 1990). Escalating pressure to deliver in the hospital, though often unnecessary, was consistently imposed on Inuit women (Kaufert & O’Neil, 1990). The number of childbirths being evacuated climbed up and up until 1980 when official policy became to evacuate all births (Kaufert & O’Neil, 1990). Inuit women were not in favour of this policy, to say the least, as it alienated them from their family, put them in an unfamiliar setting, and stripped away their cultural heritage (Kaufert & O’Neil, 1990). Some studies indicate that evacuation of births did decrease infant mortality and some concluded that the rates remained unchanged, therefore the evidence was inconclusive (Douglas, 2006). Most health professionals claim to acknowledge that evacuations cause problems for these women but insist that births should be in the hospital setting with specialized care and equipment (Kaufert & O’Neil, 1990). However, in a modern day, Inuit births are certainly not without complications. Auger, Park, Zoungrana, McHugh and Luo state that “ Aboriginal populations in Canada rank at the top of the list of disadvantaged groups with the highest rates of stillbirth in the Western World” (2013, p. 256). Therefore, the appropriation of biomedicine was not well received within the Inuit culture. Biomedical control caused drastic alterations to Inuit pregnancy and birthing traditions and separated women from their family and culture throughout these processes. However, there has been progress towards advocating for the repair of these issues with successful outcomes.

Cultural Accommodation [Ashleigh]

The Ranklin Inlet birthing center’s midwifery education program for Inuit Women

It could be argued that the Canadian government stepped in to take more control over what happened with Inuit birth and pregnancies with the best of intentions. The alarming stillbirth rates and mortality seemed to be a problem and with the medicalization of childbirth and pregnancy throughout the rest of Canada, it was inevitable in the Canadian north as well. However, that is not to say that this strong government influence and medicalization came without consequence. As noted in the previous section procedures such as the evacuation of childbirth proved to be emotionally taxing on the families involved.

A report to the Quebec Ministry of Health stated that, “this intimate, integral part of our life was taken from us and replaced by a medical model that separated our families, stole the power of the birthing experience from our women, and weakened the health, strength and spirit of our communities” (Van Wagner, Epoo, Nastapoka, & Harney, 2007, p. 384). The people of the Inuit communities clearly felt as though they were losing an important part of their culture. Some people felt so strongly opposed to the medical models and practices that were being imposed that they continued to birth in secret so that they would not have to leave their communities (Douglas, 2006). Of course, birthing in secret without any medical intervention at all could also pose risks to the mother and the baby. As a result, there was increased pressure to go back to more traditional ways. With this pressure came the development of birthing centers and midwifery training systems for Inuit communities and people with the hopes that this would help to restore an important part of culture taken from these people. Pauktuutit is an organization that has been active in trying to get midwifery back into communities and practiced more frequently. They talk about how they lobby with Inuit woman in the community to bring things back to a more traditional, community-based way without the need to travel for births (Pauktuutit, 1995). Although much of the literature reports evacuation as a completely negative experience, an article written about the experience of delivering away from home concluded that while several if not all women report feeling lonely and sad about being away from their families, they usually recounted positive experience at the hospital because according to them they felt safe and secure. (O’Driscoll, et all., 2011, p. 129). Perhaps this is due to the fact that for modern-day women in Inuit communities they have little if any experience with traditional Inuit ways in terms of pregnancy and childbirth and generally have a lack of knowledge and medical services available to them, especially if they are in remote locations. In order to restore culture loss for all generations, it was seen as vital to bring the knowledge and skills that were lost back to the communities by keeping the births local and within the communities (Wagner, Osepchook, Harney, Crosbie, & Tulugak, 2012). Van Wagner et all writes that “ The birth centers are a source of pride as a model for capacity building and cultural renewal. They facilitate family relationships and intergenerational learning in communities fractured by the impacts of colonialism and social change (2012). Birthing centers have been one of the biggest government influenced changes seen in Inuit communities. This is in an attempt to “meet in the middle” so to speak between traditional ways of birthing and modern practices and to also reduce the number of woman being flown out of their communities to give birth (Douglas, 2011). The Inuulitsivik maternities were the first birthing centers established in 1986 as a result of community activism by Inuit women as well as health care workers (Van Wagner, et all, 2012). The article by Van Wagner goes on to mention that the Inuulitsivik maternity birthing centers were developed with a set of best practice guidelines that are based on Inuit leadership, midwifery-led care, and local education of midwives (Van Wagner, et all, 2012). Additionally, the “risk assessment” in need for evacuation is completed at the Inuulitsivik birthing centers by a panel which includes Inuit midwives, community representatives and medical staff (Douglas, 2006). Doing a risk assessment decreases the number of women that need to be evacuated to larger medical centers. These maternities have provided a successful example of how biomedicine and traditional practices can work in synchronism (Douglas, 2006).The Inuulitsivik birthing centers have arguably been the most successful and are internationally recognized for integrating traditional and modern approaches to health care (Van Wagner, et all, 2012). The Rankin Inlet birthing center, in Nunavut, was established in 1993 because of the success noted with the Inuulitsavik Maternities, and it too aimed to return childbirth to the community (Douglas, 2011). However, it has not been as successful and accepted into the community (Douglas, 2011). ) Part of the problem with this birthing center according to a local informant is that it is in a region that is very different from other Inuit communities in that it was a mining community that had people from all regions and cultures living there thus lacking true traditions of its own (Douglas, V., 2011). Another problem the article discusses with the Rankin Inlet birthing center is that it is run by southern midwives and people do not necessarily trust them as they would if they were Inuit midwives (Douglas, 2011). The Rankin Inlet birthing center has been only marginally successful and has its challenges that it needs to overcome to reach its full potential for Inuit people in that area (Douglas, 2011). An important component that any birthing center needs in order to be successful in returning Inuit pregnancy and birth back to its roots is the incorporation of midwifery. At the Inuulisivik maternity birthing centers, there is academic and clinical education for Inuit women on midwifery that gives them the opportunity to be certified as midwives (Van Wagner, 2012). Van Wagner goes on to write that, “ southern midwives were hired to offer local midwifery education in collaboration with other health professionals, elders, and community leaders. Twenty years later most of the teaching is done by the local Inuit midwives.. (2012, p. 232). While southern midwives and other health professionals still contribute and are acting in teaching and providing care it is the local midwives that play a pivotal role in preserving traditional Inuit midwifery (Van Wagner, 2012). There is a critical need for midwives in the Canadian artic that are able to meet the current Canadian maternity care standards while being able to maintain the traditional knowledge, values and practices (James, O’Brien, Bourret, Kango, Gafvels, & Paradis-Pastori, 2010). Due to this critical demand, maternity care programs were established that rotate their sites throughout Nunavut to offer midwifery education to a larger amount of people (James, et al, 2010). James, et all, goes on to describe part of the program that was established in order to educate Inuit women on midwifery. James, et all, writes that “ subject matter included anatomy and physiology, pharmacology, and maternity care management in combination with Inuit traditional midwives’ and Elders’ long-standing practice of helping pregnant and birthing women” (2010, p. 5). Education programs such as this are becoming more common and widely utilized in the Canadian north and for good reason.

This video outlines midwifery in the North West Territories

Conclusion [Ashleigh]

The Inuit culture is one that upon examination reveals a great deal of unique beliefs, values and practices. Pregnancy and childbirth are no different in the sense that they too have been of cultural significance over time. A lot has gone on throughout history that has taken culture away from the Inuit people, especially in terms of their pregnancy and child birthing beliefs. Government influence and intervention in the Canadian northern regions has affected all aspects of pre and postnatal care amongst Inuit peoples. Medicalization of childbirth and pregnancy has been noted throughout North America in recent decades, and the Inuit are not naive or unharmed by this effect. The introduction of biomedicine has been instrumental in causing a cultural shift for Inuit people and taking away emotional, spiritual, and physical elements important in traditional beliefs regarding childbirth. The implications for Inuit people as a whole are not to be ignored. Birthing centers and midwifery, as well as midwifery education programs, have been a major part of restoring what cultural value and depth has been taken from Inuit people. Although there is still a long way to go, and challenges and problems still exist, the right steps are being taken to give a critical part of the Inuit culture back to the people.

References

- Auger, N., Park, A., Zoungrana, H., McHugh, N., & Luo, Z. (2013). Rates of stillbirth by gestational age and cause in Inuit and First Nations populations in Quebec. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal = Journal De L’association Medicale Canadienne, 185(6), 256-262.

- Billson, J. M., & Mancini, K. (2007). Inuit women: Their powerful spirit in a century of change. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Cahill, H. (2001). Male appropriation and medicalization of childbirth: A historical analysis. Journal Of Advanced Nursing, 33(3), 334-342. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01669.x

- Douglas, V. K. (2006). Childbirth among the Canadian Inuit: A review of the clinical and cultural literature. International Journal Of Circumpolar Health, 65(2), 117-132.

- Douglas, V. K. (2010). The Inuulitsivik maternities: Culturally appropriate midwifery and epistemological accommodation. Nursing Inquiry, 17(2), 111-117. doi:10.1111/j.1140-1800.2009.00479.x

- Douglas, V. K. (2011). The Ranklin Inlet Birthing Centre: community midwifery in the Inuit context. International Journal of Circumpolar Health 70(2) 178- 185.

- Douglas, V. K. (2013). Introduction to Aboriginal health and health care in Canada: Bridging health and healing. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company.

- Healey, G. K. & Meadows, L. M. (2008). Tradition and culture: An important determinant of Inuit women’s health. Journal of Aboriginal Health. Retrieved from: http://www.naho.ca/jah/english/jah04_01/05TraditionCulture_25-33.pdf

- James, S., O’Brien, B., Bourret, K.,Kango, N., Gafvels, K., & Paradis-Pastori, J.(2010). Meeting the needs of Nunavut Families: A community-based midwifery education program. Rural and remote health volume 10, 1335. Retrieved from: http://www.rrh.org.au/publishedarticles/article_print_1355.pdf

- Kaufert, P. A., & O’Neil, J. D. (1990). Cooptation and control: the reconstruction of Inuit birth. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 4(4), 427-442.

- O’Driscoll, T., Kelly, L., Payne, L., St. Pierre-Hansen, ,., Cromarty, H., Minty, B., & Linkewich, B. (2011). Delivering away from home: the perinatal experiences of First Nations women in Northwestern Ontario. Canadian Journal of Rural Medicine, 16(4), 126-130.

- Parry, D. C. (2008). “We wanted a birth experience, not a medical experience”: Exploring Canadian women’s use of midwifery. Health Care For Women International, 29 (8/9), 784-806. doi:10.1080/07399330802269451

- Pauktuutit Suvaguuq (1995) Midwifery. Retrieved from http://pauktuutit.ca/health/maternal-health/midwifery/

- Perinatal Care for the Inuulitsivik Health Centre, 2012. Birth: Issues in Perinatal Care, 39(3), 230-237.

- Tone, A. (2012). Medicalizing reproduction: The pill and home pregnancy tests. Journal of Sex Research, 49(4), 319-327. doi:10.1080/00224499.2012.688226

- Van Wagner, V., Epoo, B., Nastapoka, J., & Harney, E. (2007). Reclaiming birth, health, and community: midwifery in the Inuit villages of Nunavik, Canada. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 52(4), 384-391.

- Wagner, V., Osepchook, C., Harney, E., Crosbie, C., & Tulugak, M. (2012). Remote Midwifery in Nunavik, Québec, Canada: Outcomes of Perinatal Care for the Inuulitsivik Health Centre, 2012. Birth: Issues in Perinatal Care, 39(3), 230-237.