Palpation, an integral part of clinical examination, is the art of using touch to gather essential information about a patient’s health.

What is CLINICAL EXAMINATION?

Here are the PHYSICAL EXAMINATION METHODS FOR MEDICAL STUDENTS.

In this hands-on approach, physicians employ their sense of touch to assess a variety of factors, including temperature, physical characteristics, and movements.

Palpation is not just about physically examining the body; it’s about connecting with the patient and providing comfort during what can sometimes be a stressful experience.

Do not forget to read a detailed post on INSPECTION METHOD OF PHYSICAL EXAMINATION by following the link.

Table of Contents

ToggleDEFINITION: WHAT IS PALPATION?

Palpation is a clinical examination method that involves using your hands to examine a patient’s body.

It’s all about touch.

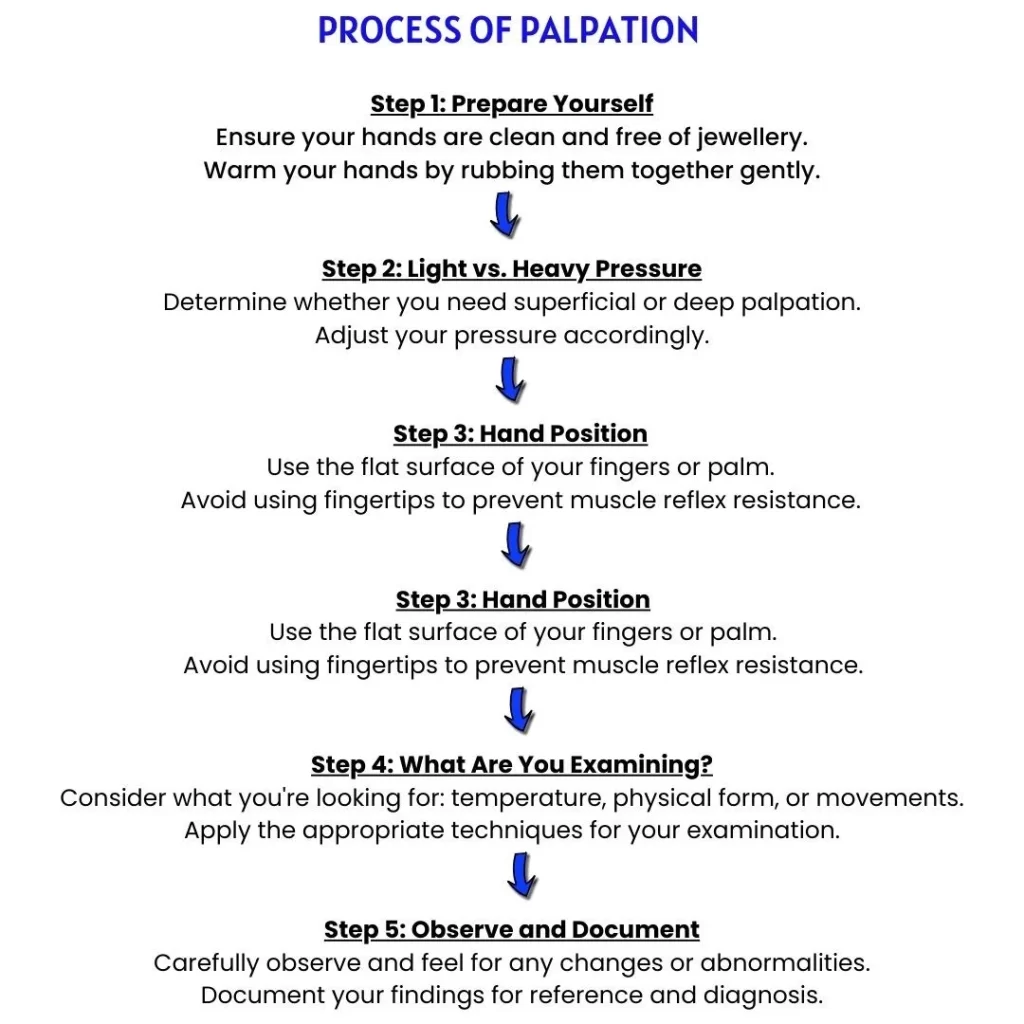

Your hands should be clean, nails trimmed, and avoid wearing rings or jewellery that could interfere with the examination.

Did you know that palpation has a rich history in medicine?

The ancient Greeks used palpation as a part of their diagnostic methods.

Hippocrates, often called the father of medicine, emphasized the importance of touch in diagnosis.

In 19th century, Dr. Rene Laennec invented the stethoscope, revolutionizing auscultation (listening to sounds in the body) and palpation.

Here is a detailed post on STETHOSCOPE, IT’S PARTS, USES, METHODS, TYPES, HOW TO BUY.

Read a very interesting post on HISTORY OF MEDICINE by following the link.

WHY WARM HANDS MATTER

Before you begin, it’s essential to rub your palms together to warm them up.

A warm touch is more comfortable for the patient, and it increases the sensitivity of your hands, helping you detect subtle changes.

Read WHY IS PATIENT COMFORT A PRIORITY DURING CLINICAL EXAMINATION?

HOW TO PALPATE?

In palpation, your hand touches, feels, and presses on the patient’s body.

The pressure applied depends on what you’re examining:

- Superficial Palpation: Use light pressure for examining surface structures.

- Deep Palpation: Apply heavy pressure when examining deeper structures.

Always use the flat surface of your fingers or palm during palpation.

Avoid dipping your fingertips into the tissues, as it can cause muscle reflex resistance.

Shyness or tickling sensations might also lead to incorrect interpretations.

Confidence, proper technique, and a serious attitude can help overcome these challenges.

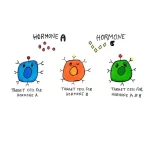

WHAT YOU CAN LEARN THROUGH PALPATION?

Palpation provides valuable information on various aspects of a patient’s condition.

READ THE INSPECTION METHOD OF PHYSICAL EXAMINATION HERE.

TEMPERATURE

- Temperature can indicate health issues.

- To assess it, use the back of your fingers and compare the patient’s temperature to your own.

- Differences in temperature are often more important than the actual degree.

- Remember that exposed skin tends to match the environmental temperature, while clothed areas reflect body temperature.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

PHYSICAL FORM

- When we perform palpation, we are essentially feeling and confirming what we observed during visual inspection.

- This involves measuring distances and various aspects using a graduated tape.

- We also use the flat of our palm to lightly touch the surface, making sure not to cause any pain or tickling sensations.

- Palpation allows us to more accurately assess the roughness or smoothness of the surface and the presence of any nodules.

Also understand why COMPARING OBSERVATIONS BETWEEN THE RIGHT AND LEFT SIDES OF THE BODY IN CLINICAL EXAMINATION is essential.

CONSISTENCY

- During palpation, we assess the consistency of the area we’re examining.

- This means we apply varying degrees of pressure to the part we’re examining and describe it as being hard, elastic, soft, cystic, and so on.

FLUCTUATING

- When fluid is trapped in a closed space within the body, it can transmit mechanical impulses from one point to another. This phenomenon is called “FLUCTUATING.”

PITTING ON PRESSURE

- If fluid is evenly distributed within body tissues, applying pressure can displace the fluid and leave a depression or “PIT” in the skin. In healthy individuals, this doesn’t typically happen with casual pressure.

- However, in diseases where there’s an accumulation of excess tissue fluid, even moderate pressure can cause a relatively long-standing depression. This condition is known as “OEDEMA.”

TEXTURE

- Texture is a description that combines the surface, form, and consistency of an area.

- It can be described as fine or coarse, rough or smooth, pliable or brittle, and so on.

TENDERNESS

- Tenderness refers to experiencing pain when an area is touched or pressure is applied.

- In healthy individuals, most body parts are not tender to touch.

- However, there are exceptions like the testes and eyeballs, which can be tender under moderate pressure, and the abdominal organs, which can be tender under heavy pressure.

- When we find tenderness, we should carefully mark the area where it exists without causing unnecessary pain to the patient.

Palpation verifies information obtained through visual inspection.

- Size: Measure the dimensions of the structure.

- Shape: Evaluate the outline or configuration.

- Surface: Inspect the outer layer for smoothness or roughness.

- Contour and Form: Analyse the overall appearance and shape.

- Consistency and Texture: Determine if it feels hard, soft, elastic, cystic, has a particular texture, or the presence of nodules.

MOVEMENTS

When we palpate (touch and feel), we pay close attention to movements.

Movements of voluntary Muscles

There are two types of movements to consider:

- Passive Movements: These are movements at the joints that occur when we gently move a person’s limbs in different directions. We carefully note how far the joints can move in various directions.

- Active Movements: These movements involve a person actively moving their limbs against resistance. This helps us determine the strength of their muscles. We can also study reflexes during palpation or percussion, which is a part of examining the nervous system. The examination of respiratory (breathing) movements is discussed in the relevant section.

Movements of Involuntary Muscles

In addition to studying voluntary muscle movements, we also examine involuntary muscle movements. Here are some aspects we consider:

- Force: We assess whether movements are vigorous, moderate, or weak.

- Direction: We feel and determine the direction of the movement.

- Tactile Vocal Fremitus: This is described when we’re examining breathing. It’s related to vibrations felt during respiration.

- Nature of Movements: Movements can be expansile (associated with an increase in the size of the organ) or non-expansile (transmitted movements). For example, the pulse is an expansile movement, while the movements seen in the epigastrium are usually non-expansile transmitted movements.

- Direction of Flow in Vessels: We figure out the direction of blood flow in blood vessels by blocking it at one end and emptying it one at a time.

- Vibrations: Sometimes, movements are associated with vibrations. We can feel these vibrations during palpation. In some cases, these vibrations can also be heard as sounds. Vibrations felt during palpation are usually linked to disease.

There are different types of vibrations:

- Thrill: This is a sensation felt through the palm, often compared to the purring of a cat. It’s frequently associated with heart movements in disease.

- Fluid Thrill: This sensation is felt through the palm when there’s a collection of fluid, and a sudden mechanical impact is applied to that fluid at a distance from where we’re palpating.

- Crepitus or Crepitation: This is a peculiar feeling and sometimes even a sound when gas or air is trapped in tiny spaces and pressed. If crepitus is felt over a bone, no matter how slight, it’s a clear sign of a bone breakage, such as a fracture.

- Location and Extent: Identify where and how much movement occurs.

- Rate: Determine how fast the movements take place.

- Rhythm: Observe if the movements follow a regular pattern.

- Duration: Note how long the movements persist.

- Force: Assess the strength or vigor of the movements.

- Direction: Determine the path or course of the movements.

- Vibrations: Detect any vibrations associated with the structure.

- Tactile and Vocal Fremitus: Evaluate vibrations felt by touch and during speech.

- Thrill: Detect a sensation akin to a cat’s purring.

- Fluid Thrill: Identify a sensation when a sudden impact displaces fluid.

- Air Crepitus: Feel for gas or air trapped in minute spaces.

- Bone Crepitus: Detect a feeling of bone roughness, which could indicate a fracture.

PRACTICAL FLOWCHART FOR PALPATION

CLINICAL APPLICATIONS AND EXAMPLES

Let’s apply these concepts to real clinical scenarios:

Scenario 1: Diagnosing Joint Pain

- Imagine a patient with joint pain in their knee.

- You start by assessing the temperature of the joint, noting any heat or swelling.

- Then, you move on to determine the physical form by measuring the size and shape of the knee.

- Next, you assess the consistency of the joint, checking if it feels soft, hard, or perhaps cystic.

- Finally, you gently check for tenderness, asking the patient if they experience pain upon touch.

Scenario 2: Detecting Abdominal Abnormalities

- In another case, a patient presents with abdominal discomfort.

- You use palpation to gather information.

- Begin with assessing the temperature of the abdominal area, feeling for any unusual warmth or coldness.

- Then, move on to evaluate the physical form by measuring the size and shape of the abdomen.

- Assess the consistency by applying pressure and determining if it feels soft, hard, or irregular.

- Lastly, carefully check for tenderness, ensuring not to cause any unnecessary discomfort to the patient.

In ancient times, physicians relied heavily on palpation, believing it could reveal a person’s character and emotional state. This practice was called “cheirosophy” or “chiromancy,” and it evolved into what we now know as palmistry or chiromancy, where palm lines are interpreted for insights into a person’s life.

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS

- What is the significance of warming your hands before palpation?

Warming your hands is not just about comfort; it enhances your sensitivity, helping you detect subtle changes in a patient’s body during palpation. It’s a crucial step in ensuring a thorough examination.

- Can palpation reveal a patient’s body temperature?

Yes, it can. By using the back of your fingers and comparing the patient’s temperature to your own, you can assess temperature differences, which can be indicative of health issues.

- How do you determine the physical characteristics of an area during palpation?

You use the flat of your palm to lightly touch the surface while measuring distances and assessing aspects like roughness, smoothness, and the presence of nodules.

- What is the role of palpation in assessing movements in the body?

Palpation is essential for studying movements, both voluntary and involuntary. It helps assess the location, extent, rate, rhythm, and force of movements, providing valuable diagnostic information.

- Are there historical references to palpation in medicine?

Palpation has a rich history, with ancient Greek physicians and even Hippocrates emphasizing its importance in diagnosis. It’s been a fundamental part of medical practice for centuries.

- How can I ensure that my palpation technique is effective and accurate?

Confidence, proper technique, and a serious attitude are key. Avoid using fingertips, as this can trigger muscle reflex resistance. Be gentle to prevent pain or tickling sensations in the patient.

- Can palpation detect abnormalities like joint pain or abdominal discomfort?

Yes, it can. Palpation can help diagnose conditions by assessing temperature, physical characteristics, consistency, and tenderness in specific areas. It’s a valuable tool for identifying abnormalities.

- What are some practical tips for conducting palpation effectively?

Ensure clean hands, warm them up, adjust your pressure (superficial or deep), use the flat surface of your fingers or palm, and consider what you’re examining (temperature, physical form, or movements). Always document your findings for reference.

- How does palpation complement other clinical examination methods?

Palpation is often used in conjunction with inspection, percussion, and auscultation to provide a comprehensive assessment of a patient’s health. It adds the crucial tactile dimension to the diagnostic process.

Leave a Reply