This post continues my occasional series on insignificant black or dark brown spots on submerged stones (see “Both sides now …” for another recent episode). I found these particular specimens on a cobble in Croasdale Beck in Cumbria, close to my regular haunts around the River Ehen and Ennerdale Water and thought that, with algae grabbing headlines for the wrong reasons yet again, I should write something positive about them. What kind of weird world do we live in when people think it strange that algae thrive in a warm, well-lit swimming pool, whilst simultaneously lauding other people who devote four years of their lives to practising jumping into that same pool?

Colonies of Chamaesiphon cf fuscus (mostly 2-3 mm in diameter) growing on a submerged cobble in Croasdale Beck, Cumbria, August 2016.

There was something about the regularity of the outlines of the dark brown / black spots on some of the more stable stones in this flashy beck that attracted my attention. I’ve scraped a lot of dark smears and smudges off rocks in the past and often been disappointed when all I find are inorganic iron or manganese deposits. Over time, one gets an eye for what is and is not an algal growth (or, for that matter, a submerged lichen) and even, in some cases, for the type of alga that formed the growth. In this case, I had a good idea, straight away, that I was looking at a member of the genus Chamaesiphon, a cyanobacterium (blue-green alga).

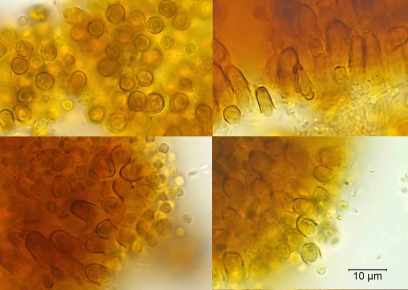

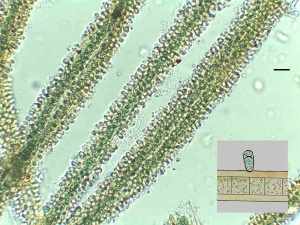

Members of this genus are unicellular and form dense mats of cells that can be difficult to photograph. I could not get a really clear view of individuals within this particular colony so, instead, have included some of Chris Carter’s photographs of another member of the genus. You can see the short, club-shaped cells, each in a sheath and many topped by small “exospores” which bud off from the mother cell to propagate the colony. The sheath has a brown tinge, presumably to the “sun-screen” compounds that we have met before in cyanobacteria. Most of the members of the genus live on submerged rocks, but a few live on other algae (see “More from the River Ehen”). Most of the rock-dwelling species indicate at least good conditions in rivers, but one species, C. polymorphus, is tolerant of more enriched conditions, which complicates use of a straight genus-level identification for rapid assessments.

Chamaesiphon polonicus from Caldbeck, Cumbria, photographed by Chris Carter. Top left: looking down on colony; other images: side views showing cells in their sheaths and, in a few instances, with exospores.

Oddly (to me at least) press coverage of the Olympic diving pool story has only used the word “algae”, never telling us what sort of alga is responsible for the problem. This is equivalent to the commentators saying that “animals” have just made a perfect leap off the 3 metre springboard, leaving the audience to work out whether the subsequent splash was made by a slug or a human.

But I should end on a positive note: better, perhaps to compare the algae not with the divers but with the judges who assign the final scores. That’s because a few minutes mooching around a stream or beside a lake can usually reveal enough from the types of algae that live there to give some insights into the health of the stream. My visits to Croasdale Beck over the past year or so have shown me enough to suggest that this little Cumbrian stream probably deserves the algal equivalent of an Olympic medal. But I doubt that we’ll get much press coverage for saying that…