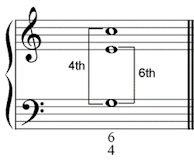

Another way of saying “2nd inversion chord” is “6/4 chord”, because the chord is built of a bass note plus the notes a 4th and a 6th higher.

For example, a bass note G, plus C and E, makes a second inversion C major chord.

Second inversion chords can only be used in a few, special circumstances. This is because they are written as “upside-down” chords, with the top note of the triad written as the lowest-sounding note, which makes them sound unstable. They should be used with care.

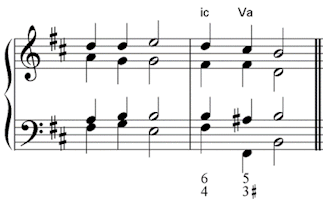

The most common place to find a 6/4 chord is in a cadential 6/4. This is a chord progression of Ic-Va: the tonic chord in second inversion moving to the dominant chord in root position.

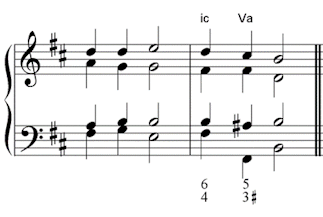

The second inversion chord is normally on a stronger beat than the dominant chord that follows it.

In this example, which is in B minor, the chords are Bm in second inversion, moving to F# major root position.

In the cadential 6/4 progression, the bass note in both chords is the same (for example, the bass note of both chords here is F#). The effect is that the bass stands still for a moment, while the chord above it changes.

In the 6/4 chord, the bass note must be doubled. In this example, the F# is doubled up in the alto, but it could be in any of the top three parts. In the following Va chord, the same doubling is used, in the same parts. (This is not an example of consecutive octaves, because the pitches don’t change. Consecutives only occur when the pitch of the notes also changes.)

The voice-leading of a cadential 6/4 is normally standardised. Each part moves by the smallest possible interval (although the bass may leap by an octave).

The 6 of 6/4 moves to the 5 of 5/3. In this example the 6 of 6/4 is D, because D is a 6th higher than the bass note F#. This D must move to C# in the same part. Here, it’s in the soprano.

The 4 of 6/4 moves to the 3 of 5/3. In this example this means B has to move to A#. You can see these notes in the tenor part.

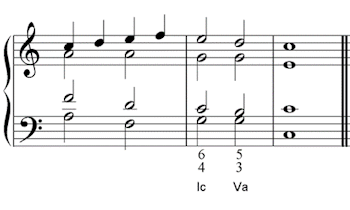

The word “cadential” is related to the word “cadence”, and this progression is most often found at a cadence, at end of a phrase, although it can also occur mid-phrase. It can be used “as is”, to make an imperfect cadence, or it can be used before a tonic root position chord, at a perfect cadence.

If you are doing a harmony exercise and need to select chords to harmonise a melody line, always check to see if you can use a cadential 6/4 as an imperfect cadence, or leading to a perfect cadence. There are never many opportunities to use a 6/4 chord, so it’s good if you can find one!

One common melody ending which works with a cadential 6/4 is the last three notes of the descending scale (mi-re-do, or Three Blind Mice), for example E, D, C in C major, which can be harmonised with Ic-Va-Ia.

The Va chord should normally be placed on a weaker beat than the Ic chord. In this example, the Ic chord falls on beat 1 and Va is on beat 3, which is weaker.

Key points:

Cadential 6/4 = Ic-Va, Strong-Weak. Parts move smoothly.