[The following blog post is the first of a series of posts highlighting archaeological sites that relate to Nebraska’s Statehood or date to the period around 1867! This series will run through September in celebration of Nebraska Archaeology Month and our state’s Sesquicentennial!]

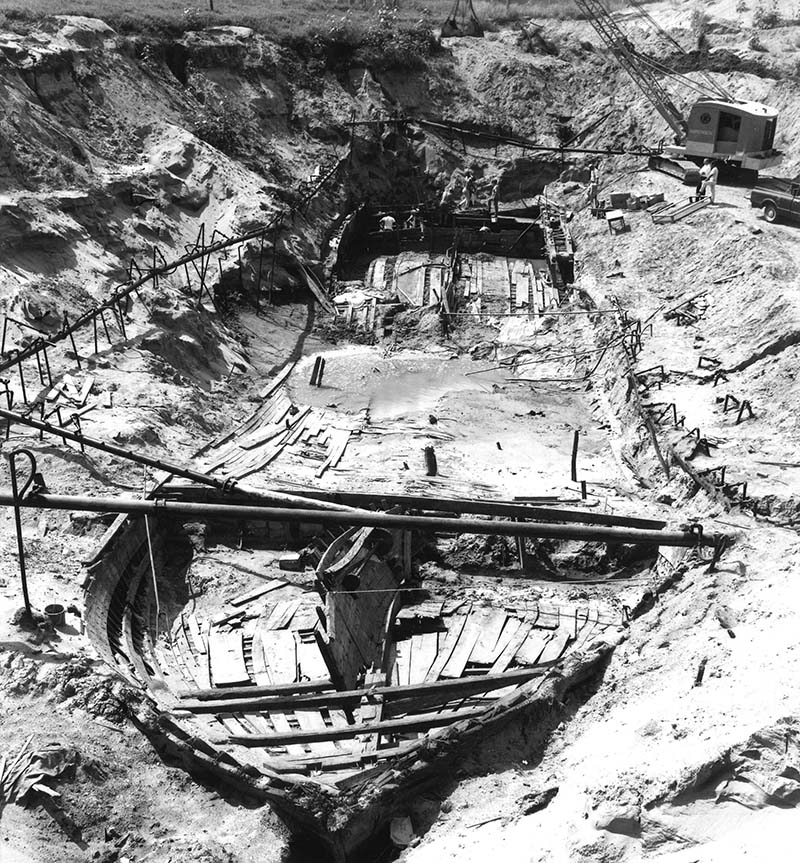

Bertrand excavation with two-thirds of the cargo removed. (Photo courtesy of Woodman of the World Magazine. Omaha, Nebraska.)

Terms like ‘shipwreck archaeology’ and ‘maritime preservation’ don’t often elicit thoughts of Nebraska. But therein extend some of the deepest roots of maritime archaeology in the Americas—30 feet deep to be exact-—in a cornfield in the Desoto Wildlife Refuge, a mile or so from the present bed of the Missouri River. In 1968, two salvors, Jesse Pursell and Sam Corbino used a magnetometer to find the wreck of the steamboat Bertrand. The vessel had, 103 years earlier, hit a ‘snag’ (part of a sunken tree) and sank on April 1st, 1865—just a few days before Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. Before sinking, Bertrand was run into the river’s bank, allowing most passengers to step off without getting their feet wet. This was in sharp contrast to the horrific demise 26 days later, of Sultana, another river steamboat near Memphis. Sultana sank due a boiler explosion resulting in more fatalities than did RMS Titanic in 1912.

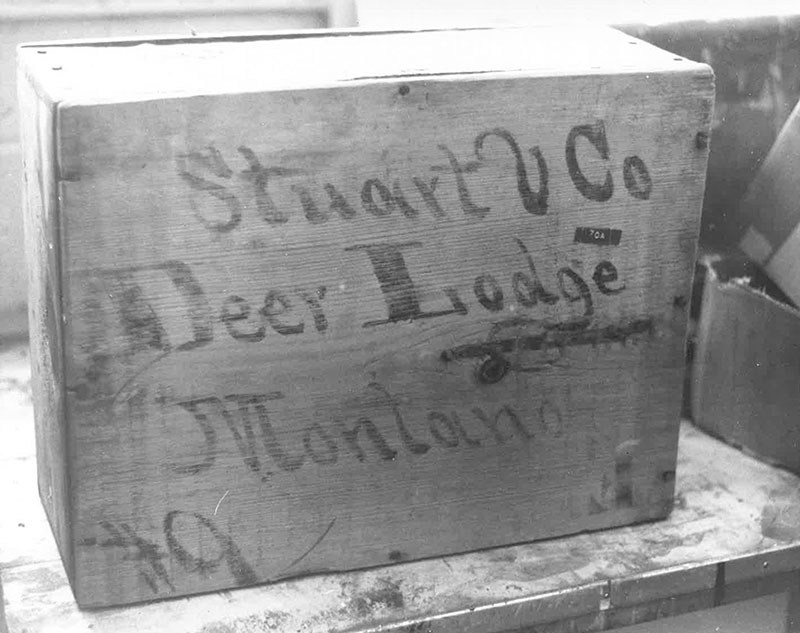

The Steamboat Bertrand’s intended destination was Deer Lodge, Montana. (Photo Credit: United States Department of the Interior. Cecil W. Stoughton, 1969.)

Traditionally, we refer to vessels made for riverways and the Great Lakes as ‘boats.’ Riverboats are built for shallow water navigation. Their capacity tends to be concentrated above the water surface rather than in a deep hull. They carried cargo and passengers equal to seagoing vessels, while maintaining a shallow draft. The inherent problem with river travel is overcoming the current on the upstream leg of any two-way journey. Before the steam engine, downriver travel was often on raft-like craft that could be recycled as cut timber at journey’s end. The physics of steam expansion enabled huge pistons to churn paddlewheels against the current, propelling large vessels upstream. The wheels could be mounted on each side of the hull or, like the Bertrand, a single large wheel at the stern. This application of steam technology was particularly important to the nation’s eastern states rich in rivers where steamboats greatly accelerated the nation’s growth.

The remains of Bertrand were lost to memory after early salvage attempts but came back to public attention in the mid-20th Century when found again by Pursell and Corbino. Rivers aren’t passive waterbodies; the Missouri reshaped itself during 103 intervening years, which explains the overlying cornfield and thirty feet of silt and gravel. Philosophical questions regarding ownership of antiquities, our physical touchstones to the past, were also being redefined. The Antiquities Act of 1906 offered protection for them on federal lands; then a 1916 organic act created the National Park Service, now the nation’s lead agency in historic preservation. Petsche cited compliance with the1935 Historic Sites Act’ in dealing with Bertrand. But just two years before Bertrand’s discovery came the 1966 National Historic Preservation Act that created a National Register and State Historic Preservation Officers with significant authority over treatment of the past.

Aerial view of the Bertrand Excavation. (Photo Credit: United States Department of the Interior. Cecil W. Stoughton, 1969.)

Treasure hunters had already begun tearing up Spanish maritime heritage sites in offshore Florida. But the salvage of antiquities from this wreck in Nebraska lacked the overtones of the grand hustle by salvors backed by slick magazines that became a decades long spectacle in Florida. Bertrand salvors were also motivated by the potential of treasure, including mercury used for refining gold. But they were apparently straightforward and open to cooperation with preservationists. Law and policy was in this case clearly on the side of salvage.

The Nebraska State Historical Society represented the interests of citizens devoted to preserving remnants of local history and archaeology. The agreement reached by all the principles was that nothing of historical value was to be lost to the public. Salvers could be reimbursed in a 60/40 % split by the government but no historic fabric forfeited. The details of how this played out in the final analysis are not clear to me from Petsche’s book.

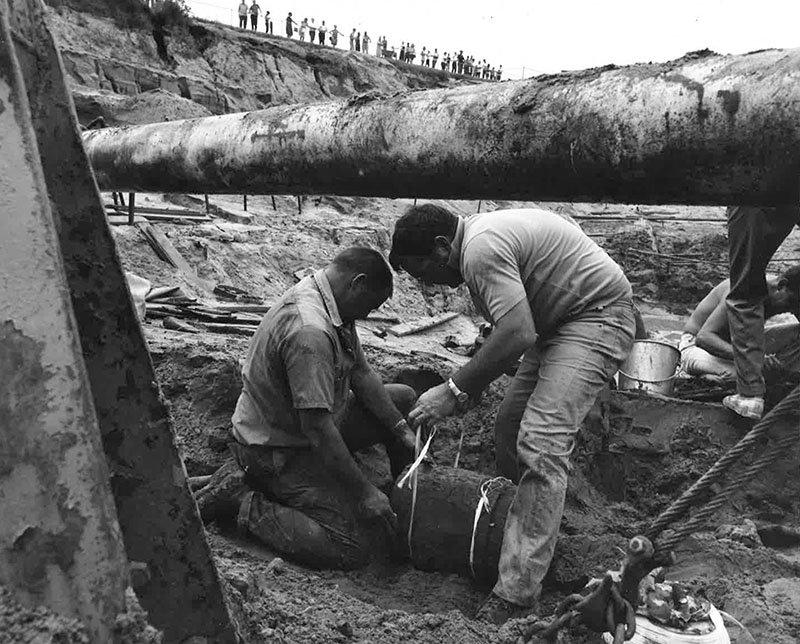

Bertrand Excavation. (Photo Credit: United States Department of the Interior. Cecil W. Stoughton, 1969.)

The conundrum presented by salvage to archaeology is understandable. People are motivated to find lost things and hope to profit from them. Federal agencies represent the public at large, and protect vestiges of the past for the public of the future. American archaeologists as represented by the Society for American Archaeology in 1968, considered themselves prehistorians. They were not adept at speaking out for historical shipwrecks nor post-Columbus sites in general. The Society for Historical Archaeology was created in 1967, the year before Bertrand was found. It included an Advisory Council on Underwater Archaeology. But if non-agency archaeologists were involved in advocating against disturbance it was not evident to me.

The Midwest Archaeological Center of the NPS in Lincoln was given archaeological control of the excavation of Bertrand but the principal investigator was an historical architect Jerome Petsche, from the NPS Washington Office. Bertrand, over a hundred years old, was being excavated through GSA contract with the US Bureau of sport Fisheries a (predecessor of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service). They followed no precedents for shipwreck excavation because, well, there weren’t any. This is clearly not the way it would happen now. The individuals involved were dealing with glitches in law and practice concerning the historical value of shipwrecks in the US—most of which were corrected by later legislation. It would be two decades before law caught up to this problem with the Abandoned Shipwreck Act.

Bertrand Excavation. (Photo Credit: United States Department of the Interior. Cecil W. Stoughton, 1969.)

There were no models for shipwreck excavation in the U.S. and the disastrous consequences of that reality were already unfolding a few hundred miles away. Namely, with the Civil War gunboat Cairo on the Yazoo River near Vicksburg. Cairo was literally pulled apart by a combination of salvers and civil war historians before NPS was given control. This is a different but related story. Put aside for a moment any thoughts of ‘underwater archaeology’ as it would be done today. What was remarkable, in the case of Bertrand, was how expeditiously the problem was addressed without a specialized infrastructure to handle it.

Bertrand lay so far beneath the land surface that water flooded any newly opened cavity. To avoid flooding while heavy machinery, including bulldozers, removed soil overburden, a system of well points (more than 200) were drilled around the hull. Water was sucked out and away before it hampered excavation. As long as the well points kept pumping, you were more likely to be run over by an historical architect on a bulldozer than see an archaeologist swim by. Petsche, under the archaeological oversight of Wil Husted and the Midwest Archeological Center, led the excavation and delivered a complete report in 1974. It was all in keeping with the unfit mélange of inappropriate legislation they operated under. But within that context the salvers acted lawfully and the professionals acted…professionally.

Careful removal of Bertrand Cargo. (Photo Credit: United States Department of the Interior. Cecil W. Stoughton, 1969.)

The Bertrand excavation marked a turning point for archaeology in a maritime context. The principal investigator was an historical architect working on a comparatively intact shipwreck, but he stayed in communication with competent land archaeologists at MWAC. Petsche also acknowledged contacts given him by George Fischer, an NPS archaeologist then beginning to specialize in shipwreck work. Petsche remarks that Fischer also “…spent several days with us in the mud and 100 degree temperatures…”

From my perspective a half century later, it seems Petsche understood how to care for historic fabric; was equipped to map historic structures; was motivated to study what he didn’t know and had the energy and savvy to put together a timely project and write a useful report. — The Steamboat Bertrand: History, Excavation and Architecture by Jerome E. Petsche has become a fundamental reference for all western riverboat investigations since. Almost equally important, the Foreword and Preface of the Bertrand report were written by Secretary of the Interior Rogers Morton and Director of the National Park Service, Ron Walker. That is important. Key figures in historic preservation on an international level wrote of the importance of a shipwreck lying in the muck-filled former channel of the Missouri river in Nebraska.

Archaeologists, including the author, are inclined to turn red at the thought of salvors and architects excavating shipwrecks. Antiquities are usually not “saved” by an act of salvage. That someone wants to salvage something it is not enough reason for a society to let them do so. Particularly since the public must care for it in perpetuity. But how Nebraska and NPS and USFW dealt with it is not a simple issue. It wouldn’t be done that way now, but—it wasn’t now, it was then—and the project’s results in that context, are hard to argue with. And the story didn’t stop there. In June 2011, the Bertrand remains and exhibits, then residing in a US Fish and Wildlife visitor center, were threatened by a flooding event. The USFW Service helped by many citizen volunteers, rolled up their sleeves and quickly packed and removed the salvaged cargo to safer quarters.

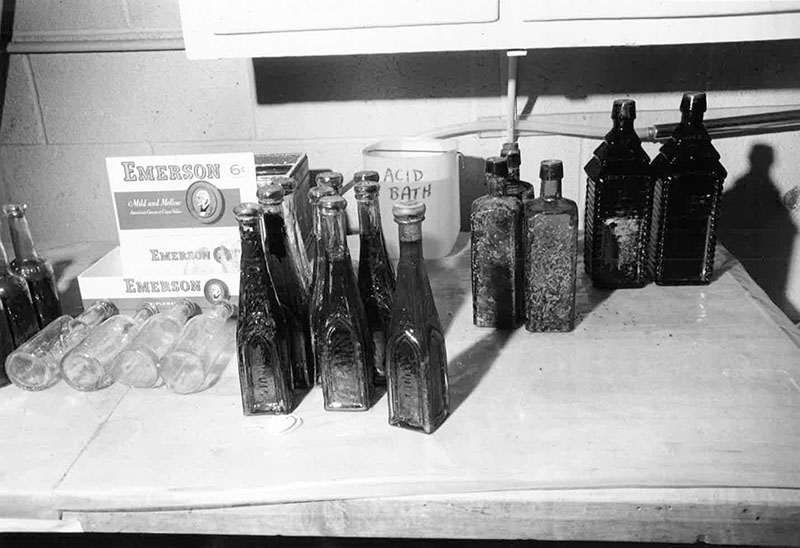

Intact bottles from the Bertrand Cargo. (Photo Credit: United States Department of the Interior. Cecil W. Stoughton, 1969.)

When excavated, shipwrecks like any material remains, never end up in truly stable environments—just different ones. Taking antiquities from a context in which they have reached a level of equilibrium, means they were taken someplace else judged temporarily secure—it’s always a gamble; consider the wealth of ruins and museums destroyed by Isis in Syria. But history came alive to the USFW, NPS and citizen volunteers who moved the threatened Bertrand remains before the floodwaters arrived. When the Nebraskan public buys into shipwreck archaeology with their sweat, it should be of note to agencies and archaeologists alike.

Example of the degree of preservation found at the Steamboat Bertrand site. (Photo Credit: United States Department of the Interior. Cecil W. Stoughton, 1969.)

About the Author –

Dan Lenihan was the founding chief of the NPS Submerged Resources Center (SRC).

He ran the National Reservoir Inundation from 1975 to 1980 and the Submerged Cultural Resources Unit (SCRU) 1980 thru 1999. When he retired, Larry Murphy became Chief and the name was changed to Submerged Resources Center (SRC). Dan worked for SRC as a rehired annuitant off and on, from 1999 to 2009 on various projects. He also published several books including Submerged (a popular book about the SRC) Underwater Wonders of the National Parks and co-authored three novels.

Interested in learning more about the Steamboat Bertrand?

Read The Steamboat Bertrand: History, Excavation, and Architecture by Jerome E. Petsche (as referenced above) at nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/bertrand/bertrand.pdf.

View the collections uncovered during excavation at the Steamboat Bertrand museum located inside the visitor center at DeSoto National Wildlife Refuge. For more information, visit fws.gov/refuge/Desoto/wildlife_and_habitat/steamboat_bertrand.html.

Learn about the efforts undertaken by the Gerald. R. Ford Conservation Center in Omaha to conserve the metal found during the Steamboat Bertrand excavations – youtube.com/watch?v=VmzrQVQstHA&t=238s.