It used to be we’d get a day or two of rain each week, enough to keep the lawns green and fungi growing, but now it seems everything happens in bunches. Weather comes in and stays for a week or two, and it has been like that lately. The latest low pressure system has taken two weeks to slowly creep out of the midwest and arrive, as of Wednesday, in Rochester, NY. Hopefully by the time I post this it will have moved out over the Atlantic. Its spin has brought wave after wave of rain, and it has rained at least a little almost every day. There was even a flash flood alert in there somewhere, but it never happened here. The Ashuelot River has overrun its banks in the lowest places but those places, often hay fields, are left open and empty so it can, and there is no damage done.

If you decide to be a nature blogger the first thing you learn is, you take what comes. You don’t have to sing in the rain but you do have to put up with it, so you dress for weather and out you go. I happen to like occasional days like those shown in these photos, so they don’t bother me. You find, if you pay attention, that on windy days the wind doesn’t usually blow constantly, so if you wait a bit the flower you want a shot of will stop whipping around. The same is true with rain; there are often moments or even hours when it holds off. But you have to pay attention and catch the right times, otherwise you’ll learn how to shoot with one hand and hold your umbrella with the other.

Rainy days are best for photos of things like lichens, because their color and form are at their peak when they’re hydrated. A dry lichen can look very different, so trying to match its color with one in a lichen guide can sometimes be frustrating. Foliose lichens especially, like the Tuckermannopsis in the above photo, can change drastically. Mosses, lichens, and fungi are all at their best on rainy days, so those are the best days to look for them. Species of the above lichen could be cilliaris, which is also called the fringed wrinkle lichen.

My phone camera decided this view of a shadbush needed to be impressionistic, so that’s what I got. Since I’ve always liked the impressionist artists I was okay with it. Shadbush (Amelanchier) is usually the earliest white flowered roadside tree to bloom, followed quickly by the various cherries, and finally the apples and crabapples.

The common name shadbush comes from the shad fish, which used to run in great numbers in our rivers at about the same time it blossomed. It is also called shadblow, serviceberry, Juneberry, wild plum, sugar plum, and Saskatoon, and each name comes with its own story. I used to work with someone who swore up and down that his ornamental Amelanchier trees were not shadbushes, when in fact they were just cultivated varieties (cultivars) of the shadbush. If the original tree is taken from the wild and improved upon by man by selective breeding or other means, that doesn’t mean it becomes a different tree. One look at the flowers tells the whole story.

The buds of the shadbush, as far as I know, are unique and hard to confuse with any others, so if your Amelanchier has buds like these it is a shadbush. People get upset when they discover that their high priced ornamental tree has the heart of a roadside tramp, but that’s because they don’t understand how many years and how much work it took to “improve” upon what was found in nature. Cultivars can have double the number of flowers that roadside trees have but they are also often bred for disease resistance and other desirable, unseen characteristics as well, and that’s why they cost so much. It can take 20 years or more to develop a “new” tree, and even longer to profit from the time and effort.

Wood anemones have sprung up but with all the clouds it has been hard to find an open flower. Finally, one cloudy day this one said “Hey, look at me,” so I grabbed a shot while I could. If ever there was a sun lover this is it, but on this day it could wait no longer.

I went to the Beaver Brook natural area to see if the hobblebushes that lived there were blossoming, and found them in full bloom, along with many trilliums. This one pictured had taken on an unusual upright shape. I usually see them grow low to the ground with their branches hidden by last year’s fallen leaves. They’re easy to trip on, and that’s how this bush hobbles you. I was careful not to trip and end up in the brook.

Or at least, the bushes were half way blooming. All the unopened buds in the center are the fertile flowers that do all the work and the larger, prettier flowers around the outer edges are the sterile flowers, just there to entice insects into stopping in for a visit. Hobblebushes are a native viburnum, one of over 200 species worldwide, and they are one of our most beautiful spring flowering shrubs.

Red elderberries go from purple buds to white flowers, so I’d guess by now I should go back and see the flowers. The flower heads are pyramidal; quite different from the large, flat flower heads of the common elderberry.

While I was at Beaver Brook I decided to check on the disappearing waterfall, which runs only after we have a certain amount of rain. What draws me to this scene is the mosses. Mosses grow slowly here, often taking many decades to cover a stone wall, and that’s because it has always been relatively dry with a normal average of an inch or so of rain each week, but turn up the rainfall and what you see here will happen. Most of that moss is due to splash over from the stream and or/ water runoff from above, and it’s beautiful and unusual enough to sometimes make people stand in line, waiting to get a photo. I saw them stacked three deep here one day, but if ever we live in a time with twice the average rainfall people will walk right by this spot without giving it a second glance, because then everything will look like this.

By the way, if you’re interested in mosses the BBC did a fascinating one hour show about them. Just Google “The Magical World of Moss on BBC.” It’s well worth watching.

Beaver Brook was rushing along at a pretty good clip and the trees along its banks were greening up.

But not all the new leaves were green.

Beech buds are breaking and there are beautiful angel wings everywhere in the forest.

In the garden the cartoonish flowers of henbit have finally appeared. Not that long ago I could count on them being one of the first flowers I showed here in spring but now they bloom as much as a month later. Why hens peck at them I don’t know, but that’s why they’re called henbit. They’re in the mint family and the leaves and flowers are edible, with a slightly sweet and peppery flavor.

How intense the blue of scilla was on a cloudy day. This and other spring flowering bulbs are having an extended bloom this year I’ve noticed, most likely because it has been on the cool side for a week or two.

The blue of grape hyacinths was just as intense. My color finding software calls it slate blue, indigo or royal blue, depending on what area I put the pointer on. These plants have nothing to do with either grapes or hyacinths. They’re actually in the asparagus family, but more beautiful than their cousins, I think. I like the small white ring that surrounds the flower’s opening, most likely there to entice insects.

A slightly different colored glory of the snow has come along. These are very pretty flowers, almost like a larger version of scilla, but not quite the same shape. If I had more sun in my yard I’d grow them all.

The small leaved PJM rhododendrons had just come into bloom when I took this photo. The plants were originally developed in Massachusetts and are now every bit as common as Forsythias in this area. In fact, the two plants are often planted together. Forsythia blooms usually a week or so before the rhododendron but yellow and purple flowers blooming together is a common sight in store and bank parking areas in spring.

The old fashioned bleeding hearts are blooming nicely. They can get quite big in the garden but they die back in summer. This can leave quite a big hole in a perennial border, so they take a bit of planning before you just go ahead and plant one anywhere. They are native to northern China, Korea and Japan and despite a few drawbacks are well worth growing. They also do well as stand alone plants due to their size, and since they don’t mind shade they look good planted here and there under trees. That’s the way the plant pictured above is used in a local park.

Even the ferns are being held back by the cool, wet weather; this sensitive fern is one of only two or three I’ve seen trying to open. A sunny day or two will perk them up and will also mean an explosion of growth, so I’m hoping I can bring you a sunnier post in the near future.

Cinnamon ferns are in all stages of growth but I have yet to see one fully opened.

Lower down on its stem this fern had a visitor. I was near a pond and mayflies were hatching. According to what I read online the dull opaque color of the wings means this mayfly was at the “subimagio stage,” halfway between the nymph and adult stages. This is when they are most vulnerable, so that explains why it was in hiding on this fern. A single hatching can produce many millions of them, so there were probably others around. They are among the most ancient types of insects still living, having been here since 100 million years before the dinosaurs. I’m glad they’re still with us; I think they’re quite beautiful. I hope everyone is able to get out and see all of the wonders of spring.

As I stood and watched the mists slowly rising this morning I wondered what view was more beautiful than this. ~Hal Borland

Thanks for coming by.

This is also a beard lichen called bristly beard (Usnea hirta.) many lichens grow so slowly that they can take decades to grow a fraction of an inch. They are thought to be among the oldest living things on earth.

This is also a beard lichen called bristly beard (Usnea hirta.) many lichens grow so slowly that they can take decades to grow a fraction of an inch. They are thought to be among the oldest living things on earth.

Common powderhorn lichens (Cladonia coniocraea) look just like lipstick powderhorns, but without the red tip. The spores are released from the pointed tip. These were also growing on a decaying log.

Common powderhorn lichens (Cladonia coniocraea) look just like lipstick powderhorns, but without the red tip. The spores are released from the pointed tip. These were also growing on a decaying log.

This is another fructicose lichen called beard lichen (Usnea.) It grows on trees instead of on the ground and is very common in pines and hemlocks in our area. It’s sometimes called old man’s beard. Most lichens are very sensitive to air pollution and will not grow where the air isn’t clean.

This is another fructicose lichen called beard lichen (Usnea.) It grows on trees instead of on the ground and is very common in pines and hemlocks in our area. It’s sometimes called old man’s beard. Most lichens are very sensitive to air pollution and will not grow where the air isn’t clean.  Fringed wrinkle lichens (Tuckermannopsis Americana) always remind me of leaf lettuce. This type of lichen is foliose, or leaf like. These are also quite common in this area-on conifers especially-and can be quite colorful. When a large pine or hemlock falls the upper branches are often covered with this type of lichen.

Fringed wrinkle lichens (Tuckermannopsis Americana) always remind me of leaf lettuce. This type of lichen is foliose, or leaf like. These are also quite common in this area-on conifers especially-and can be quite colorful. When a large pine or hemlock falls the upper branches are often covered with this type of lichen.  Our rocks are very old here. I took a picture of this one because it looked like it had been folded before it had fully cooled however many millions of years ago. It was covered in moss and lichens.

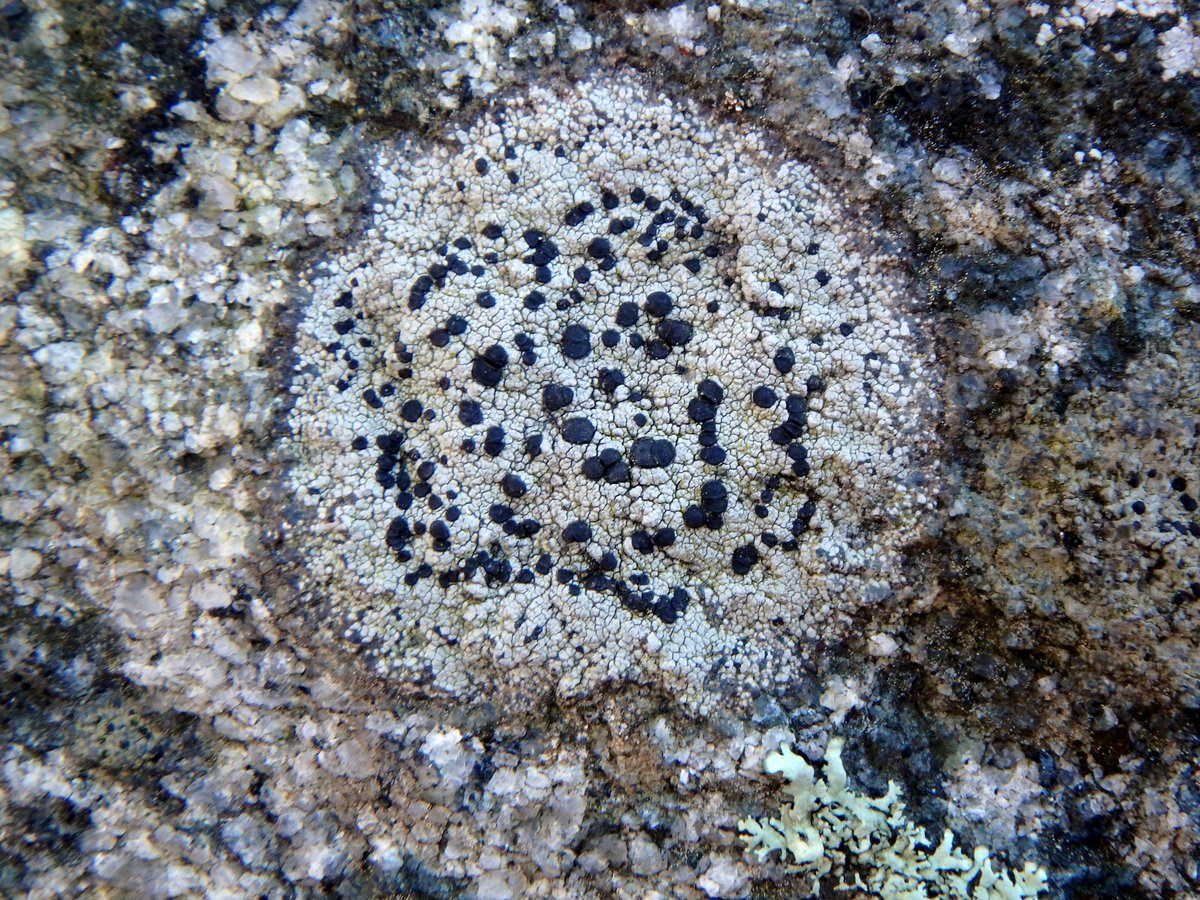

Our rocks are very old here. I took a picture of this one because it looked like it had been folded before it had fully cooled however many millions of years ago. It was covered in moss and lichens.  I’ve been watching this blue lichen for over a year now. When I showed it in this blog last year I said it was purple, but my color finding software has corrected that mistake. This type of lichen is known as a Crustose or crusty lichen because it forms a flat crust that can’t be lifted or peeled off of whatever it is growing on. In my experience blue lichens are quite rare.

I’ve been watching this blue lichen for over a year now. When I showed it in this blog last year I said it was purple, but my color finding software has corrected that mistake. This type of lichen is known as a Crustose or crusty lichen because it forms a flat crust that can’t be lifted or peeled off of whatever it is growing on. In my experience blue lichens are quite rare.

This spot of yellow cructose lichen was also about the size of a dime and grew in full sun among mosses and other lichens. I think this might be a sulphur fire dot lichen (Caloplaca flavoirescens,) but I’m not 100% sure. I don’t see too many yellow lichens.

This spot of yellow cructose lichen was also about the size of a dime and grew in full sun among mosses and other lichens. I think this might be a sulphur fire dot lichen (Caloplaca flavoirescens,) but I’m not 100% sure. I don’t see too many yellow lichens.

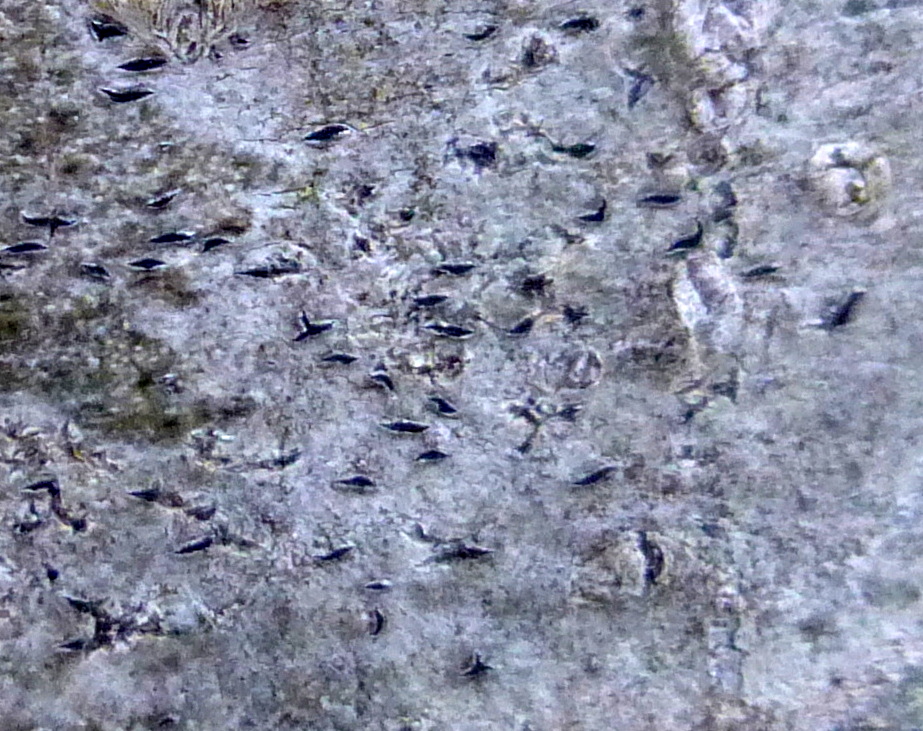

The chances of my finding a single stone for a second time are very slim unless it is a large boulder that is easy to remember. I took a picture of this stone because I liked its colors and grain patterns, but I didn’t see the small dark spot in the center until I looked at the photo. As it turns out this dark spot is midnight blue, according to my color finding software. I don’t really know if this is a lichen or a mineral embedded in the stone but midnight blue is a rare color indeed. Azurite and malachite can be deep blue, so it is possible that it is a mineral and not a lichen. The trouble is I don’t remember where the stone is so I can take a second look with a magnifying glass.

The chances of my finding a single stone for a second time are very slim unless it is a large boulder that is easy to remember. I took a picture of this stone because I liked its colors and grain patterns, but I didn’t see the small dark spot in the center until I looked at the photo. As it turns out this dark spot is midnight blue, according to my color finding software. I don’t really know if this is a lichen or a mineral embedded in the stone but midnight blue is a rare color indeed. Azurite and malachite can be deep blue, so it is possible that it is a mineral and not a lichen. The trouble is I don’t remember where the stone is so I can take a second look with a magnifying glass.  I’m fairly certain that this is an example of a liverwort rather than a lichen because it was growing in the wet, saturated sand at the water’s edge. A liverwort is a flowerless, spore producing plant. Liverworts like wet places but I haven’t seen too many lichens growing in wet sand. A closer look shows a “vein” (nerve) running down the center of each leave and lichens don’t have this feature that I know of. Liverworts get their name from early herbalists who thought that some of these plants resembled a human liver.

I’m fairly certain that this is an example of a liverwort rather than a lichen because it was growing in the wet, saturated sand at the water’s edge. A liverwort is a flowerless, spore producing plant. Liverworts like wet places but I haven’t seen too many lichens growing in wet sand. A closer look shows a “vein” (nerve) running down the center of each leave and lichens don’t have this feature that I know of. Liverworts get their name from early herbalists who thought that some of these plants resembled a human liver.