THE SIN.

It was the holy Sabbath, and — as some have told — Easter Day, the high Sabbath of the Christian year. The matin-bell was clanging in the old chapel by the Wear, where Lambtons, sire and son, for many a year had made their solemn vows. Here and there throughout the woodland all about troops of maidens with downcast eyes, or sprightly children, and sober matrons, and stout yeomen dressed in homespun, were seen wending their way to keep the feast of the resurrection with sacrament and psalm. The squire, leading his goodly dame, and his household gravely following, bent his steps to the sacred shrine. All his strong sons and daughters fair were in the train — all save one, and that, not then but afterwards, the heir of all his ancient lands and name. John was the spoiled laddie of the house, wayward and wild; nor recked he of good or evil, could he but come at all he wished. Vainly rang the bell for him, and the sweet strains of worship had no charm for him. He loved not to kneel in prayer, or to join in pious chant. Better far did he love the bright free air of the beauteous spring time, with the song of merry birds and the plash of leaping waters. And so when others passed to prayer he took his gay strong rod, and, sauntering down the rich green banks of the Wear, set himself down to fish. Long he sat and sore fretted that no silly trout would take his clever bait. Ill could he brook that he, forsooth, should toil and watch for nought; so it came at last that he cursed his luck, and cursed the fish, and cursed silvery water that yielded him no sport. Oaths were a bait that could not wholly fail. Did not the old wives tell him that “curses, like chickens, would come home to roost”? Perchance his would come again; he cared not so that none should mock him for his folly on the holy day. Once again he threw the line, when, lo! there was a tug, a strain, a catch. And such a catch! It pulled so hard he thought it was a salmon, or a bigger prize. But when it reached the water’s top, ah me! it was a little ugly worm — an eft, a thing of slime, and fearsome to look upon, with gaping mouth, and nine little months on each side its head besides. Wrenching it from his hook, the angry John flung it from him far away, and it alighted in the silent waters of a well on the river banks. To him came a stranger, old and worshipful, who bade him good morrow, and asked him what sport. To the which greeting John roughly answered, “I think I’ve catched the devil” — and so he had, though he believed not what he idly said. The aged stranger looked into the dear, bright waters of the well, and there espied the filthy newt, which seeing, he devoutly crossed himself and sighed for the woes the fish-fiend would surely bring upon the home and lands of Lambton.

THE CURSE.

The evil worm throve fast in the clear sweet water of the well, and it soon outgrew the bounds of its watery cradle, nor could its huge maw be staid with fluttering midge and lowly moss. It grew and grew most wondrously, and sought another resting place and other food. In the centre of the river was a peeping rook, grassy and moist. Thither by day the elfish worm would come, and, coiling itself round and round, basking in the sun, slumber to the music of the prattling stream. By nightfall it would wend its way to Pensher Hill, coiling its long length around until it circled the hill’s wide base. But, spirit of evil as it was, the night was its hour of going forth to seek its prey. And, ever as it grew, it roamed further afield to stay its hunger; and as it fed it grew in length and bulk, until there seemed no end to its devouring or its size. It drained the cows of their milky treasure, and worried the lambs in their play, seizing them, rending them, and crushing their tender bones in its now gigantic jaws. When it had laid desolate all the region on one bank of the river, it passed over to the other side, and made its way, eating all things as it went, towards Lambton Hall, where the old squire sat sullen and sad in the gloaming of his age, sorrowing for his four dead sons, but most of all for the living one who ere this had gone to the wars. Great was the terror of the squire’s household when the scaly dragon was seen making for the hall. The old steward gave counsels of peace, and at his bidding the great trough in the courtyard was filled with sweet new milk. The grim worm drew near to the trough, and shortly drained it to the last drop; thus his hunger and rage were soothed, and he crawled back to his rocky lair in the bed of the river. Sure as the morning was his return day by day; and if perchance there was shortness of milk the trough would hold the yield of nine cows he would suddenly rage with great fury, lashing his vast tail round tall trees, and tearing them up by the roots. Far and wide the bruit of the cursed worm went out, and many a gallant knight sought Lambton Hall, girt with right trusty lance or sword, bravely mounted and armed from head to foot; but the strong worm wound round and round the knights as erst around the trees, and crushed both horse and rider in its folds; or, if some true cut severed the loathsome carcass, the pieces came together quickly, and the worm was as before. Sadness and weeping were in Lambton Hall. All the land lay blighted, and the stricken folks could only groan and tell their beads, awaiting Heaven’s good will.

THE PENITENT’S RETURN.

It must be told that he who had brought this evil to pass had laid to heart his devious ways, and had gone to fight the Saracen in the Holy Land. Seven long years he wandered and fought, and then turned his footsteps hastening homeward. What woe is this. ‘Twere meet that the heir’s returning should be the beginning of gladness for those who had mourned him absent. Death had spared the old man only this one of his many sons: why then comes he not forth to welcome, as of old the father came to meet the trembling prodigal? Alas! grief upon grief had well-nigh wasted the last drop of oil in the old man’s lamp of life. Yet a father’s love was hidden beneath the ashes of a smitten heart, and knightly John was lovingly embraced. Strange tidings had that woeful sire to tell his son; and the son, learning of the fate so often dared and suffered by the knights who had so bravely sought to slay the impish worm, warily, as became a well-trained warrior, pondered the greatness of the peril — not that he shrank, but that he would win deliverance to his father’s house, and solace to his own most troubled heart, albeit he died in winning it. He had brought this curse on all he loved, and it was no meet atonement that he should simply die, and so add grief to the grief he fain would heal.

THE WITCH.

Now there dwelt in a lonely hut an aged wife, wrinkled and yellow, with matted locks and piercing eyes, and rugged, screaming voice. Her commune was with the dead and the lost, and the outer darkness whence come pestilence, devilry, despair, and death to the children of men. To her the troubled chieftain went, that he might know the dreadful truth of all this mischief, and perhaps also how the ill should be undone. The witch was crooning over her smouldering fire of stolen wood, humming the mystic chants of her darksome craft, as she dozed above the dying embers. Brave John had come to learn the worst and best, if any best there was, or worse than had been yet. The haggard wife lifted upon him her piercing eyes, and in hot breath as of the nether pit reproached him as the cause of all this death and grief. But when she read his true heart in the tear-dimmed eyes, and knew that he was ready to do all man might do in such a strait, she bade him tell the castle armourer to stud his coat of mail with spear heads, sharp-edged as well as pointed, that so the brute, enwinding itself about him, should, the more it pressed, the more hurt itself and waste its strength. Moreover she named the dreadful price of victory. He must vow to Heaven that the first living thing he met on his return from the encounter should be by him slain in sacrifice of thanks, for that, if he failed, the nine mouths of the dragon must needs be stopped, and so nine Lambtons, sire and son, should die by shock of accident or battle.

THE COMBAT.

By prayer and fasting, making his peace with Heaven, and donning his spear-studded suit of mail, brave John made ready for the fight; then sought his father’s benison. Then thought he of his vow, and, fearing much how it might be, he bade his father listen till he heard his bugle blast, then slip his favourite hound, that this, his faithful friend in life, might be the first of living things to meet the victor in the strife, and so become his victim for the vow. Then forth he went about the time the monster was on his way to gorge himself at the courtyard trough. Not long was the knight in espying the huge beast rolling over the mead in hungry haste; but what a monster, and how small the ugly eft he once had likened to the devil! This wax the devil in good sooth —

Between his head and his tayle

Was xxii fote withouten fayle;

His body was liken a wine tonne.

He shone full bright agenst the sunne.

His eyes were bright as any glasse,

His scales were hard as any brasse.

The knight lifted his soul in prayer, then rushed upon the dragon, might and main, as he paused on the river bank. Fiercely he struck and smote, now here, now there, but naught availed. The serpent rose, and, seizing hold, wrapped the strong heir of Lambton in its deadly coils. Then was the witch’s wisdom seen. The more the serpent pressed, the more it cut those hard scales no sword in mortal hand could more than dint. Its pain fed its fury, and it clutched so hard that the razor like spears cut it in many a piece, and the severed masses floating down the blood-stained stream, were never seen or heard of more.

THE FATAL VOW.

The combat over, the victor dashed the throbbing head and loathsome tayle of the worm’s corse from off his path, and, hasting homewards, blew a blast upon his horn so loud and joyous, that the woods were filled with far resounding music. The father, waiting that welcome signal, forgot his part, and, leaving his hound in leash, himself ran forth to meet his victor boy. Not joy, but tears and heavy groans, returned the father’s greeting. Amazement and great sorrow seized upon the gallant warrior in the triumphal hour; for his vow, that dreadful vow, was falling like mist of death between the father and the son. And yet this dear old father must not, shall not die. What said the witch-wife with her shrill, screaming voice? That if the heir of Lambton failed him of his vow, nine heirs of Lambton, one for every one of those false mouths upon the dragon’s head, should die by force. Good, so let it be. This aged lord has borne the brunt of all these ills; spare him, just Heaven, and let nine heirs of Lambton pay the vow, in painful deaths away from couch and loving hands to tend them. Heaven heard and registered the vow. The eager hound was slipped from the thongs that held him; and on he rushed to the well-known bugle call, and when he reached his noble master’s feet, the hand that should have stroked his silken head drew forth a dagger and stabbed him to the heart. Alack-a-day, this too late offering served not to stave away the dreary fate from nine succeeding Lambton lords. Some in battle, others in hunting, each by some ill chance, met death, until the vow was redeemed, as Henry Lambton, member for the City of Durham, died in his carriage, on June 26, 1761, when crossing the new bridge in Lambton Park.

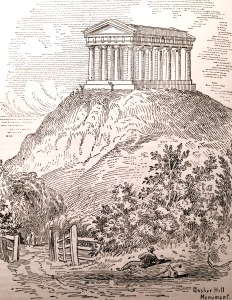

THE PENSHER HILL MONUMENT.

The foundation stone of the monument that adorns the hill around which the Lambton Worm is traditionally said to have coiled itself, was laid on Wednesday, August 28th, 1844, by Thomas, Earl of Zetland, Grand Master of the Free and Accepted Masons of England. The monument was erected to the memory of John George Lambton, Earl of Durham, who died at Cowes on the 28th of July, 1840, for “the distinguished services he rendered to his country, as an honest, able, and patriotic statesman, and as the enlightened and liberal friend to the improvement of the people in morals, education, and scientific acquirements.” Pensher Hill was chosen as the site, owing to its having been for many years connected with the property of the Lambton family. It was estimated at the time that no fewer than 30,000 persons congregated at Pensher to witness the ceremony of laying the foundation stone. The following inscription, which was placed on the lower stone, was tastefully engraved on a brass plate: —

This stone was laid by

Thomas, Earl of Zetland

Grand Master of the Free and Accepted Masons of

England, assisted by

The Brethren of the Provinces of Durham and North-

umberland, on the 28th of August, 1844,

Being the Foundation Stone of a Memorial to be erected

To the Memory of

John George, Earl of Durham,

who,

After representing the County of Durham in Parliament

For fifteen years,

Was raised to the Peerage,

And subsequently held the offices of

Lord Privy Seal, Ambassador Extraordinary and

Minister at the Court of St. Petersburgh, and

Govenor-General of Canada.

He died on the 28th of July, 1840, in the 49th year

of his age.

–

This Monument will be erected

By the private subscriptions of his fellow-countrymen.

Admirers of his distinguished talents

and Exemplary private Virtues.

–

John and Benjamin Green, Architects.

The design of the monument is copied from the Temple of Theseus. The dimensions, however, are exactly double those of the original. Thus, the columns of the Temple of Theseus are 3 ft. 3 in. in diameter, while those of the Durham Memorial are 6 ft. 6 in. The total length of the structure is 100 ft., the width 53 ft., and the height from the ground 70 ft. at one end, and 62 ft. at the other. There are eighteen columns — four at each end, and seven at the flanks or sides, counting two of the end ones on each flank. The monument occupies so commanding and conspicuous a position that it can be seen from almost all parts of the district between the lower reaches of the Tyne and the Wear.