[English version below]

Desde su nacimiento, la antropología siempre se ha apoyado en la imagen para aprender y transmitir el conocimiento sobre las sociedades humanas. Partiendo de ser un mero soporte a la palabra, y a veces infravalorado, lo visual ha pasado a ser eje fundamental de los trabajos etnográficos, junto con la utilización de técnicas que exploran distintos sentidos, y dotan a las experiencias humanas de una perspectiva multisensorial y multimedial.

El nacimiento del mundo digital ha impulsado la incorporación de las nuevas tecnologías en la investigación, acelerando los planteamientos hipertextuales y el alejamiento de la vieja linealidad. La ruptura de la barrera entre lo virtual y lo real provoca nuevos comportamientos sociales, y lo digital puede ser objeto, método o campo en el estudio antropológico.

Lucy, el origen de la paleoantropología digital

La paleoantropología no se ha quedado al margen de este desarrollo, y casos como el de Lucy así lo demuestran. El esqueleto de esta pequeña Australopithecus afarensis no se ha hecho famoso por su descripción científica de Donald Johanson y otros en 1976, sino seguramente por otros muchos motivos de índole social, acompañados por diversos mecanismos que utilizan todos los sentidos para evocar en nosotros una tierna imagen de Lucy.

Recordamos la icónica imagen de sus huesos colocados anatómicamente sobre un fondo negro, las decenas de reconstrucciones en dibujos, pósters y esculturas realizadas por paleoartistas, muchas de ellas inspiraciones para modelizaciones 3D de australopitecos empleadas en documentales y vídeos de Youtube, la música de Lucy in the sky with diamonds (no me negaréis que os está resonando ahora mismo), conferencias como las del mismo Johanson, en las que la mayoría de sus diapositivas y palabras están orientadas a tocar las emociones de los asistentes, reproducciones virtuales 3D e imprimibles de todos sus huesos, infografías sobre cómo murió Lucy al caer de un árbol… Creo que Lucy, «la abuela de todos», la pequeña y tierna Lucy, marcó el camino para el nacimiento de la paleoantropología digital.

Reproducción de Lucy, Australopithecus afarensis (Museo de la Evolución Humana, Burgos), por Elisabeth Daynès. Crédito: Roberto Sáez

Discusiones científicas en redes sociales

El ejemplo más reciente de paleoantropología digital ha sido el vivido hace pocos días en Twitter y Facebook, cuando Chris Stringer lanzó su propuesta de buscar nuevos términos para «arcaico» y «moderno» a la hora de referirnos a las diferencias morfológicas entre determinados grupos humanos del Pleistoceno medio y final.

Se suele asociar «humano moderno» a la morfología anatómicamente moderna de nuestra especie Homo sapiens (cráneo alto y redondeado, cara pequeña, mentón, huesos ligeros con pelvis estrecha, etc.). Para evitar la discrepancia de opiniones sobre ese uso y confusión con el desarrollo de los «comportamientos modernos» humanos, Stringer propuso el empleo de apomórfico (rasgos especializados que son únicos a un grupo o especie) en vez de moderno, y plesiomórfico (rasgos que comparten con su grupo o especie antepasada) en vez de arcaico.

Tras varias interacciones en esas redes sociales, Stringer enriqueció su propuesta con la sugerencia de Mike Plavcan sobre usar mejor los términos de basal (cerca de la posición antepasada en un árbol o filogenia) y derivado (caracteres especializados, no presentes en el antepasado). De esta forma, el cráneo Omo Kibish 1 sería un Homo sapiens derivado (dHs) y los cráneos Jebel Irhoud 1 y Omo Kibish 2 serían Homo sapiens basales (bHs). Los homininos de la Sima de los Huesos serían Homo neanderthalensis basales (bHn) y los neandertales clásicos como La Ferrassie 1 y Forbes’ Quarry serían Homo neanderthalensis derivados (dHn).

«Quiero agradecer a todos los que participaron en este debate constructivamente, que ha mostrado el lado positivo de las redes sociales para lograr más en una semana de discusión, de lo que he conseguido en varios años de discursos académicos», concluyó Stringer.

Replicas de Omo Kibish 2 (izd) y reconstrucción de Omo Kibish 1 por Day&Stringer (dch). Crédito: Chris Stringer

Homo naledi: de la cueva a las redes

Otro caso que quiero mencionar de paleoantropología digital, es el conseguido por Lee Berger y el gran equipo (en calidad y en tamaño) que descubrió, investigó y publicó la especie Homo naledi.

En 2013 se publica en Facebook una oferta de trabajo para realizar una excavación en Rising Star, en vez de usar un anuncio de empleo por medios ordinarios y a través de colegas académicos. Así, rápidamente juntaron un equipo de seis arqueólogas experimentadas para poder llegar hasta la cámara de Dinaledi a través de la complicadísima forma de la cueva. A finales de 2013 se realiza la campaña de excavación durante tres semanas, y se van compartiendo y comentando en línea los hallazgos a través de Twitter (con la etiqueta #RisingStar), con una enorme repercusión mediática.

En 2014 se publica de nuevo en Facebook una oferta de trabajo para el estudio de los materiales recuperados. Rápidamente se seleccionan 40 participantes. En mayo de 2014 se analiza el enorme conjunto de fósiles durante 5 semanas. El número tan alto de investigadores de distintas partes del mundo, promueve la interacción y colaboración para refinar el entendimiento de esta nueva especie.

Finalmente, en 2015 se publican los resultados en eLife, revista científica con revisión por pares y acceso abierto en línea. Los investigadores tienen sesiones por plataformas de videoconferencia para charlar sobre el proyecto con estudiantes de todo el mundo. Se publican los ficheros escaneados de más de 200 fósiles en el repositorio de acceso abierto Morphosource, alojado por Duke University. Cualquier persona puede descargarse los ficheros para analizarlos e imprimirlos. Y se publica una aplicación de realidad virtual que permite a cualquier persona visitar Dinaledi, una de las cámaras de Rising Star de donde proceden los fósiles de Homo naledi.

Por tanto, la paleoantropología digital aborda el estudio de la evolución humana conectando investigadores mediante prácticas, experiencias y tecnologías digitales que hacen crecer y retroalimentar el conocimiento de una manera rápida, más amplia, y accesible a investigadores y educadores de cualquier país e institución. ¿Es un concepto novedoso? Puede que sí, pero no hay duda de que en breve perderá el apellido, porque la paleoantropología ya no puede entenderse sin lo digital.

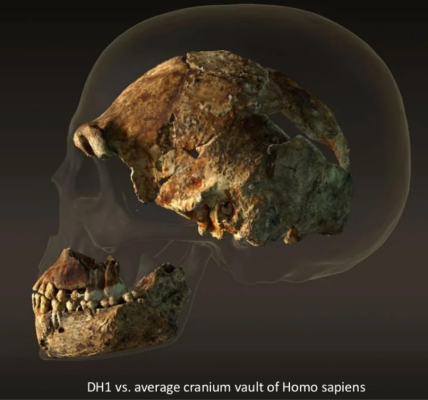

Cráneo de Homo naledi (DH1) en comparación con tamaño promedio de cráneo de Homo sapiens. Crédito: Lee Berger

What is Digital Paleoanthropology?

Since its birth, anthropology has always relied on images to learn and transmit knowledge about human societies. From being a mere support to the word, and sometimes undervalued, the visual approach has become a fundamental axis of ethnographic work, along with the use of techniques that explore different senses, and provide human experiences with a multisensory and multimedia perspective.

The birth of the digital world has boosted the incorporation of new technologies in research, accelerating hypertextual approaches and the move away from the old linearity. The breaking down of the barrier between the virtual and the real provokes new social behaviors, and the digital can be an object, method or field in anthropological study.

Lucy, the origin of digital paleoanthropology

Paleoanthropology has not remained on the sidelines of this development, and cases such as Lucy prove it. The skeleton of this little Australopithecus afarensis has not become famous for its scientific description published by Donald Johanson and others in 1976, but certainly for many other reasons of a social nature, accompanied by various mechanisms that use all the senses to evoke in our mind a tender image of Lucy.

We remember the iconic image of her bones anatomically placed over a black background, the dozens of reconstructions in drawings, posters and sculptures made by paleoartists, many of them inspirations for 3D models of australopithecines used in documentaries and Youtube videos, the music of Lucy in the sky with diamonds (which you will not deny that it is echoing in your mind right now), lectures such as those of Johanson himself, in which most of his slides and words are oriented to touch the emotions of the audience, 3D virtual and printable reproductions of all her bones, infographics about how Lucy died when she fell from a tree… I think Lucy, «everybody’s grandmother», little tender Lucy, marked the way for the birth of digital palaeoanthropology.

Scientific discussions on social networks

The latest example of digital paleoanthropology would be the one we lived a few days ago on Twitter and Facebook, when Chris Stringer launched his proposal to find new terms for ‘archaic’ and ‘modern’ when referring to the morphological differences between certain human groups of the Middle and Late Pleistocene periods.

‘Modern human’ is often associated with the anatomically modern morphology of our species Homo sapiens (high and rounded skull, small face, chin, light bones with narrow pelvis, etc.). Because of differing views on that use, and to avoid confusion with the development of ‘modern human’ behaviors, Stringer proposed the use of ‘apomorphic’ (specialized traits that are unique to a group or species) instead of modern, and ‘plesiomorphic’ (traits that are shared with the ancestor group or species) instead of archaic.

After several interactions in these social networks, Stringer enriched his proposal by using Mike Plavcan’s suggestion to better adopt the terms ‘basal’ (near the ancestral position on a tree or phylogeny) and ‘derived’ (specialised, not-ancestral traits). Thus, the Omo Kibish 1 skull would be a derived Homo sapiens (dHs) and the Jebel Irhoud 1 and Omo Kibish 2 skulls would be basal Homo sapiens (bHs). The hominins from Sima de los Huesos would be basal Homo neanderthalensis (bHn) and the classic Neanderthals such as La Ferrassie 1 and Forbes’ Quarry would be derived Homo neanderthalensis (dHn).

«I want to thank everyone who engaged in this debate constructively, which showed the positive side of social media in achieving more in a week’s discussion than I have managed in several years of academic discourse» – Stringer concluded.

Homo naledi: from the cave to the net

Another case I want to mention of digital paleoanthropology, is the one achieved by Lee Berger and the great team (in quality and in size) that discovered, researched and published the species Homo naledi.

In 2013 they posted a job offer on Facebook to execute an excavation at Rising Star, instead of using a job advertisement by ordinary means and through academic colleagues. Thus, they quickly put together a team of six experienced archaeologists in order to reach the Dinaledi chamber through the very complicated shape of the cave. At the end of 2013, the excavation campaign was carried out for three weeks, and the findings were shared and commented online via Twitter (with the hashtag #RisingStar), with enormous media coverage.

In 2014, a new job offer for the study of recovered materials is posted again on Facebook. Quickly, 40 participants are selected. In May 2014, the huge fossil assemblage was analysed over a 5-week period. The large number of researchers from different parts of the world promotes interaction and collaboration to refine the understanding of this new species.

Finally, in 2015 the results are published in eLife, a peer-reviewed scientific journal with open access online. Researchers have sessions via videoconferencing platforms to chat about the project with students from around the world. Scanned files of more than 200 fossils are published in the open-access repository Morphosource, hosted by Duke University. Anyone can download the files for analysis and printing. And they publish a virtual reality application that allows anyone to visit Dinaledi, one of the Rising Star chambers where the Homo naledi fossils came from.

Thus, digital paleoanthropology approaches the study of human evolution by connecting researchers through digital practices, experiences and technologies that make knowledge grow and feed back in a fast, broader, and accessible way to researchers and educators from any country and institution. Is it a novel concept? Probably yes, but there is no doubt that it will soon lose the adjective, because paleoanthropology can no longer be understood without the digital.

¡’¡¡Qué interesante Roberto, descubrir la parte positiva de las redes sociales que en tantas ocasiones no aportan gran cosa y roban mucho tiempo!!!

Me gustaLe gusta a 1 persona

Gracias Roberto, las redes y la tecnología seguro que reducirán los tiempos para alcanzar consensos concluyentes de manera radical.

Un abrazo.

Me gustaLe gusta a 1 persona