February 13: Said Lady Elizabeth Eastlake; “Photography is…the sworn witness of everything presented to her view.”

February 13: Said Lady Elizabeth Eastlake; “Photography is…the sworn witness of everything presented to her view.”

Today’s date coincides with the life events of two photographers, one a deaf mute, the other a policeman, both of whom used photography as witness.

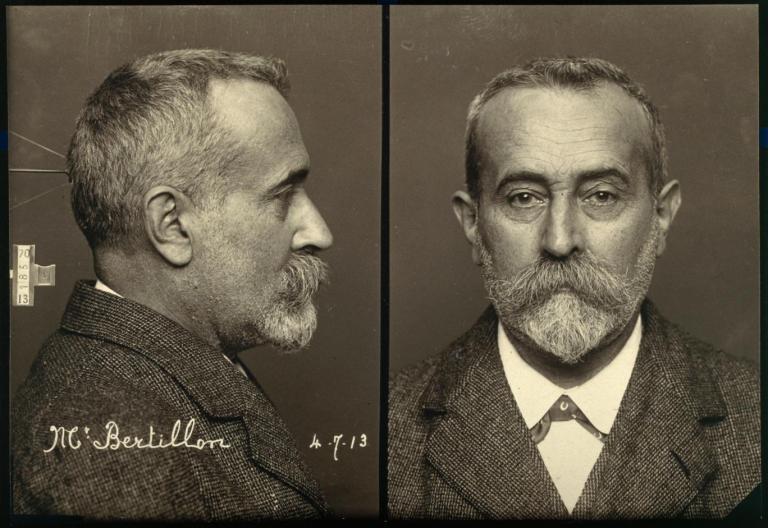

Alphonse Bertillon, who died on this date in 1914 is now well known as the Parisian police official who was the first to recognize that by constructing a classification system of visual features police could more easily recognise criminals and repeat offenders.

His scientific classifications are based on anthropometry, the study of human variation. He systemised the measuring and cataloguing of criminals’ distinguishing features on individual index cards.

His scientific classifications are based on anthropometry, the study of human variation. He systemised the measuring and cataloguing of criminals’ distinguishing features on individual index cards.

Anthropometry was based on ideas related to phrenology, yet Bertillon himself was doubtful about phrenology:

I do not feel convinced that it is the lack of symmetry in the visage, or the size of the orbit, or the shape of the jaw, which make a man an evil-doer.

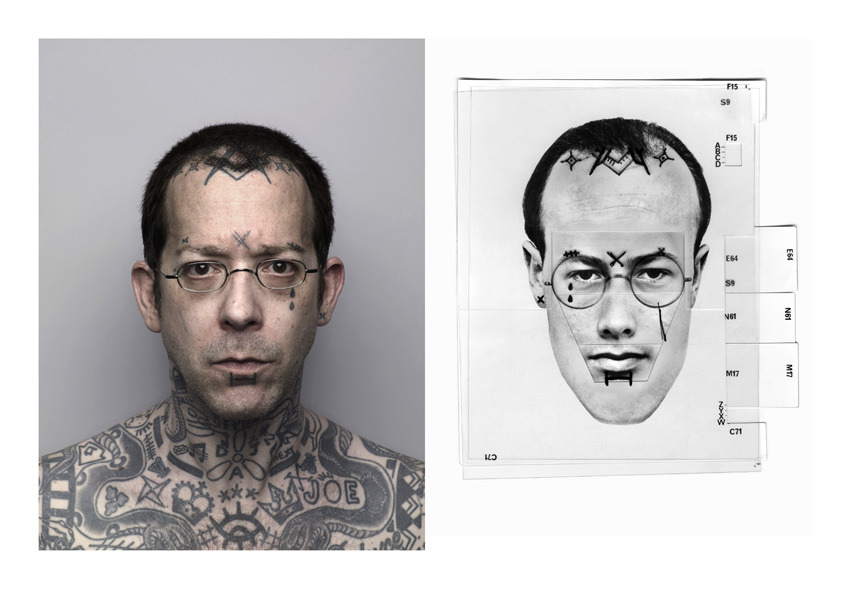

Bertillon’s system for entering face descriptions into criminal files he called portrait parle. This involved classifying the shapes of the eyes, nose, mouth, and other features into a coded lexicon that could be used as shorthand. However, the code was extensive and hard to teach to all the police in France, so photography became the preferred identification system. Institutionalised in the classic the mug shot, the camera was the enabling technology, since it made the collection of these measurements nearly instant.

His very practical concern was to create a record that would identify an individual based on metrics, rather than to detain them on the basis of signs of criminal tendencies that phrenology (‘profiling’ we’d call it now, and just as dubious) claimed to identify. This system, invented in 1879, became known as the Bertillon system, or bertillonage, and quickly gained wide acceptance as a reliable, scientific method of criminal investigation.

It worked. Recidivism was recognised as an increasing burden on law enforcement in France. Recidivists were difficult to identify, because arrestees had only been identified by name and address, and sometimes a picture. But appearance and addresses change, and anyone could lie about their name. In 1884 alone, after Bertillon’s system using photography and systematic measurements was accepted, 241 repeat offenders were captured, thus establishing its effectiveness.

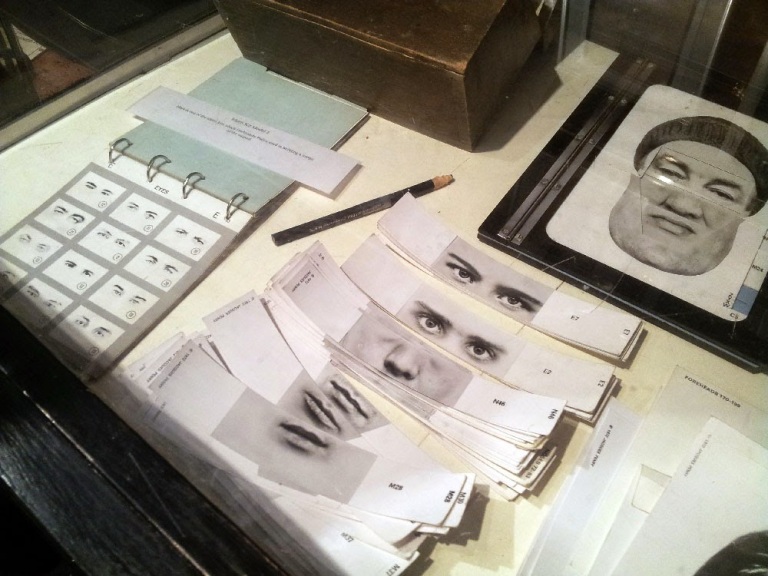

Although his measurement system was superseded by the use of fingerprints, the mug shot has retained its value. His portrait parle system evolved into interchangeable templates of separate facial features, and its dependents were Photofit in the UK, Smith & Wesson’s Identi-Kit in the US and PortraitPad.

Jacques Penry (an alias; his real name was Bill Ryan) was a photographer fascinated by facial topography from as early as the 1930s. In 1939 he published his book How to read character from the face in which he claimed to be able to determine personality instantly from appearance: philosophers, for example, would show a marked development of the lower cheek muscles, while idiots and simpletons would have a receding forehead. His method, which was another application of phrenology, but based on photographs of facial features, would, he proposed, cleanse society of “criminals, mental deficits, neurasthenics and vocational misfits.”

In 1968, Jacques Penry presented his photo-fit system to the Home Office in London. Narrow strips with 40 versions of each facial feature cut from photographs of faces and an index; they were cheap enough to replace police sketch artists.

Photo-FIT was first used successfully in arresting John Earnest Bennett in Nottingham for the murder of James Cameron in Islington in October 1970 when the composite jogged a shop assistant’s memory. Soon though, policemen found that Photofit portraits of suspects often looked nothing like the criminals that were eventually caught: the Penry-method clearly had its limits, as Giles Revell and Matt Wiley demonstrate with their Photofit self-portrait exercise.

By 1988, computer programmes for facial profiling (“E-fits”) came into use and Photofit kits were binned. Since then ‘evolutionary’ recognition-based processes incorporated into software assist identification of suspects with a high degree of success.

Bertillon also promoted the use of crime scene photography, standardising a technique of photographing a murder victim from above using a camera with a wide angle lens on a high tripod, lens facing down, to map the crime scene and all the details in the immediate vicinity of a victim’s body and the body’s position in situ before investigators disturbed the scene. Forensic measurements could be taken from the images any time afterward.

Upon its invention photography had been quickly recognised as a means of identification, of preserving a ‘likeness’. As the early commentator on the medium, Lady Elizabeth Eastlake, remarked in 1857;

Photography is the purveyor of such knowledge to the world. She is the sworn witness of everything presented to her view… her business is to give evidence of facts, as minutely and as impartially as, to our shame, only an unreasoning machine can give.

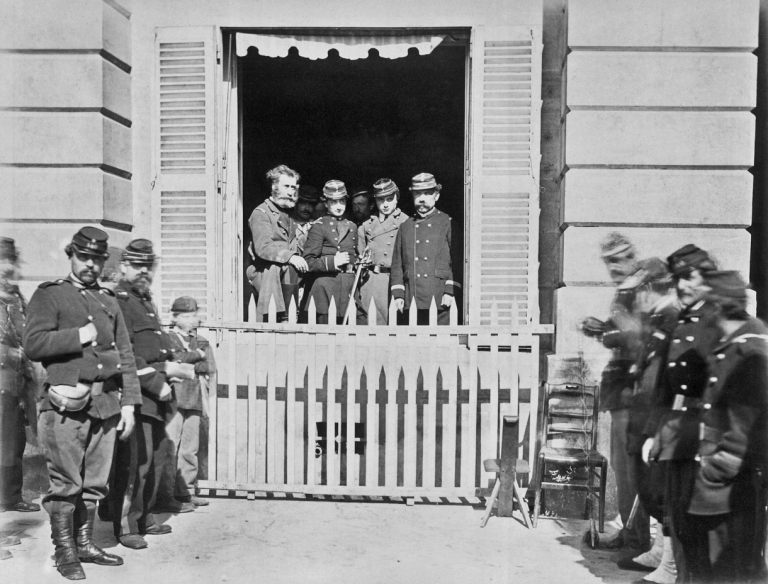

It has become a much debated legend in the history of photography that it was just such evidence that was used after the Paris Commune, to identify and convict, and execute, some of those involved.

The Paris Commune proclaimed itself on March 28, 1871, and lasted two months, coming after France was defeated in the Franco-Prussian War (declared by France on July 19, 1870) and the Prussians’ crippling siege of Paris (August to December, 1870), which severed the capital from the rest of the country. The Government of National Defense, on January 28, 1871, submitted to an armistice on humiliating terms. After their months of deprivation during the siege, resulting in the death of many, the city of Paris responded by forming its own government, the Commune, a term emotionally associated with French republicanism of 1792. The Commune faced two enemies within striking distance of the city, the Prussian army and the government army stationed at Versailles. Ultimately, the leader of the GND, Adolphe Thiers, resorted to armed force to regain control of the city, and the government army (called the Versaillais) marched on Paris on May 21 and engaged in civil combat for a week known as the semaine sanglante (Bloody Week’) to end the Commune.

A number of established photographers of various specialisations, among them Andre-Adolphe-Eugene Disderi, Jules Andrieu, François-Marie-Alexandre Gobinet Franck de Villecholle (known as Franck), Pierre Petit, Alphonse Liebert, Hippolyte Collard, and Gaudenzio Marconi competed to sell views concerning the Franco-Prussian War and the Commune and by mid-June, photographs were selling to residents and tourists.

Among them were many made by Bruno Braquehais, born in Dieppe in 1823 and who died on this date in 1875. Deaf from a young age, he worked as a lithographer in Caen until 1850, when he met photographer Alexis Gouin (ca. 1790s–1855) in whose studio he worked and which he later took over, first having set up his own in which he specialised in rather provocative hand-coloured nudes ostensibly made for artists (which made them legal at the time). More importantly, he was the one photographer who got out on the street during the Commune to make photographs, 109 of which he published in a booklet, Paris During the Commune.

Though deaf and mute, his photographs are eloquent records of one of the earliest battles in history to be photographed, the first four being the Mexican-American War (1846–48), the Crimean War (1854–56), Indian Rebellion of 1857 and the Second Italian War of Independence (1859). He joins the photographers of the American Civil War (1861–65), and the early photojournalists, Mathew Brady, Alexander Gardner, George N. Barnard and Timothy H. O’Sullivan in using photography to convey human conflict.

By the Commune’s end at least 40,000 insurgents were in police files, some 10,000 sentenced by summary justice to prison, death or deportation to penal colonies, and probably 10,000 slain. Among the arrested was the pacifist and painter Gustave Courbet, captured after the Semaine Sanglante in the house of a friend where he had spent the week. He was sentenced to six months in prison and fined for his part in the destruction of the Vendôme Column.

The first political photomontages appeared after the Commune; Crimes of the Commune by Eugène Appert and Martyrs of La Roquette Hippolyte Vauvray, faked pictures, with an anti-communard purpose. Episodes from the Commune were restaged with the help of actors in costume enacting the executions of hostages by insurgents in May 1871.

This period was when public authorities first used photography as a means of judicial identification. Photographs were taken, particularly by Eugène Appert, of arrested communards in Versailles prisons. Any who had escaped arrest found their images by Braquehais and others had been sent to border checkpoints to identify them. Police authorities attempted to control distribution of such pictures and a decree forbade their sale at the end of 1871, on the grounds that such pictures disturbed public order, reminding people of distressing events. Only “purely artistic” pictures of Paris ruins escaped this policy.

Photography’s business had indeed become ‘to give evidence of facts, as minutely and as impartially as, to our shame, only an unreasoning machine can give.’