In March of 1813, The Critical Review: Or, Annals of Literature (pages 317-328) published an anonymous review of the recently published novel Pride and Prejudice, whose author although also anonymous is identified as having written Sense and Sensibility. The reviewer likes the novel and thinks that it offers some useful information on the subject of marriage to the magazine’s “fair readers.” He writes:

In March of 1813, The Critical Review: Or, Annals of Literature (pages 317-328) published an anonymous review of the recently published novel Pride and Prejudice, whose author although also anonymous is identified as having written Sense and Sensibility. The reviewer likes the novel and thinks that it offers some useful information on the subject of marriage to the magazine’s “fair readers.” He writes:

“The sentiments, which are dispersed over the work, do great credit to the sense and sensibility of the authoress. The line she draws between the prudent and the mercenary in matrimonial concerns, may be useful to our fair readers—therefore we extract the part.

The reviewer concludes with some praise for the novel:

We cannot conclude, without repeating our approbation of this performance, which rises very superior to any novel we have lately met with in the delineation of domestic scenes. Nor is there one character which appears flat, or obtrudes itself upon the notice of the reader with troublesome impertinence. There is not one person in the drama with whom we could readily dispense;—they have all their proper places; and fill their several stations, with great credit to themselves, and much satisfaction to the reader.

The full review is reproduced below.

Art. X.—Pride and Prejudice, a Novel, in Three, Vols.. By the Author of Sense and Sensibility. London, Egerton, 1813.

Instead of the whole interest of the tale hanging upon one or two characters, as is generally the case in novels, the fair author of the present introduces us, at once, to a whole family, every individual of which excites the interest, and very agreeably divides the attention of the reader.

Mr. Bennet, the father of this family, is represented as a man of abilities, but of a sarcastic humour, and combining a good deal of caprice and reserve in his composition. He possesses an estate of about two thousand a year, and lives at Longbourne, in Hertfordshire, a pleasant walk from the market town of Meryton. This gentleman’s estate is made to descend, in default of male issue, to a distant relation. Mr. Bennet, captivated by a handsome face and the appearance of good temper, had married early in life the daughter of a country attorney,

‘A woman of mean understanding, little information, and uncertain temper. When she was discontented, she fancied herself nervous. The business of her life was to get her daughters married; its solace was visiting and news.’

At a very early period of his marriage, Mr. Bennet finds, that a pretty face is but sorry compensation for the absence of common sense; and that youth and the appearance of good nature, with the want of other good qualities, will not make a rational companion or an estimable wife. The consequence of this discovery of the ill effects of an unequal marriage, is the defalcation of all real affection, confidence, and respect on the side of Mr. Bennet towards his wife. His views of domestic comfort being overthrown, he seeks consolation for a disappointment, which he had brought upon himself, by indulging his fondness for a country life and his love for study. Being, as we said, a man of abilities and sense, though with some peculiarities and eccentricities, he contrives not to be out of temper with the follies which his wife discovers, and is contented to laugh and be amused with her want of decorum and propriety.

‘This,’ as our sensible author remarks, ‘is not the sort of happiness which a man would, in general, wish to owe to his wife; but where other powers of entertainment are wanting, the true philosopher will derive benefit from such as are given.’

However this may be, though Mr. Bennet finds amusement in absurdity, it is by no means of advantage to his five daughters, who, with the help of their silly mother, are looking out for husbands. Jane, the eldest daughter, is very beautiful, and possesses great feeling, good sense, equanimity, cheerfulness, and elegance of manners. Elizabeth, the second, is represented as combining quickness of perception and strength of mind, with a playful vivacity something like that of her father, joined with a handsome person. Mary is a female pedant, affecting great wisdom, though saturated with stupidity. ‘She is a lady,’ (as Mr. Bennet says), ‘of deep reflection, who reads great books and makes extracts.’ Kitty is weak-spirited and fretful; but Miss Lydia, the youngest,

‘is a stout, well-grown girl of fifteen, with a fine complexion and good humoured countenance; a favourite with her mother, whose affection had brought her into public at an early age. She had high animal spirits, and a sort of self-consequence.’

This young lady is mad after the officers who are quartered at Meryton; and from the attentions of these beaux garçons, Miss Lydia becomes a most decided flirt.

Although these young ladies claim a great share of the reader’s interest and attention, none calls forth our admiration so much as Elizabeth, whose archness and sweetness of manner render her a very attractive object in the family piece. She is in fact the Beatrice of the tale; and falls in love on much the same principles of contrariety. This family of worthies are informed, that Netherfield Park, which is situated near to the Longbourn estate, is let to a young single gentleman of good fortune. The intelligence puts Mrs. Bennet on the Qui vive; or, in a more homely phrase, quite on the high fidgets. In her own mind, Mrs. B. augurs not only great good from this occurrence, but secretly determines, that the said gentleman shall and must fix upon one of her girls for a wife. She therefore exhorts her husband to visit the new-comer without delay; but perhaps the following conjugal dialogue will exhibit Mr. and Mrs. Bennet to the best advantage.

‘ “My dear Mr. Bennet, have you heard, that Netherfield Park is let at last?” Mr. Bennet replied, that he had not. “But it is,” returned she; “for Mrs. Long has just been here, and she told me all about it.” Mr. Bennet made no answer. “Do you not want to know who has taken it?” cried his wife impatiently. “You want to tell me, and I have no objection to hearing it.” This was invitation enough. “Why, my dear, you must know Mrs. Long says, that Netherfield is taken by a young man of large fortune from the north of England.” “What is his name?” “Bingley.” “Is he married or single?” “Oh, single, my dear, to be sure! A single man of large fortune; four or five thousand a year. What a fine thing for our girls!” “How so? How can it affect them?” “My dear Mr. Bennet,” replied his wife, “how can you be so tiresome! You must know, that I am thinking of his marrying one of them.” “Is that his design in settling here?” “Design! nonsense, how can you talk so. But it is very likely, that he may fall in love with one of them? and therefore you must visit him as soon as he comes.” “I see no occasion for that—you and the girls may go, or you may send them by themselves, which perhaps will be still better; for as you are as handsome as any one of them, Mr. Bingley might like you the best of the party.” “My dear, you flatter me. I certainly have had my share of beauty, but I do not pretend to be any thing extraordinary now. When a woman has five grown-up daughters, she ought to give over thinking of her own beauty.” “In such cases, a woman has not often much beauty to think of.” “But, my dear, you must indeed go and see Mr. Bingley when he comes into the neighbourhood.” “It is more than I engage for, I assure you.” “But consider your daughters. Only think what an establishment it would be for one of them. Sir William and Lady Lucas are determined to go merely on that account; for in general you know they visit no new comers. Indeed you must go; for it will be impossible for us to visit him if you do not.” “You are over scrupulous, surely. I dare say Mr. Bingley will be very glad to see you; and I will send a few lines by you, to assure him of my hearty consent to his marrying whichever he chooses of the girls; though I must throw in a good word for my little Lizzy.” “I desire you will do no such thing. Lizzy is not a bit better than the others; and I am sure she is not half so handsome as Jane; nor half so good-humoured as Lydia. But you are always giving her the preference.” “They have none of them much to recommend them,” replied he; “they are all silly and ignorant, like other girls; but Lizzy has something more of quickness than her sisters.” “Mr. Bennet, how can you abuse your own children in such a way? You take delight in vexing me. You have no compassion on my poor nerves.” “You mistake me, my dear. I have a high respect for your nerves. They are my old friends. I have heard you mention them with consideration these twenty years at least.” “Ah! you do not know what I suffer.” “But I hope you will get over it, and live to see many young men of four thousand a year come into the neighbourhood.” “It will be no use to us, if twenty such should come, since you will not visit them.” “Depend upon it, my dear, that when there are twenty, I will visit them all.” ’

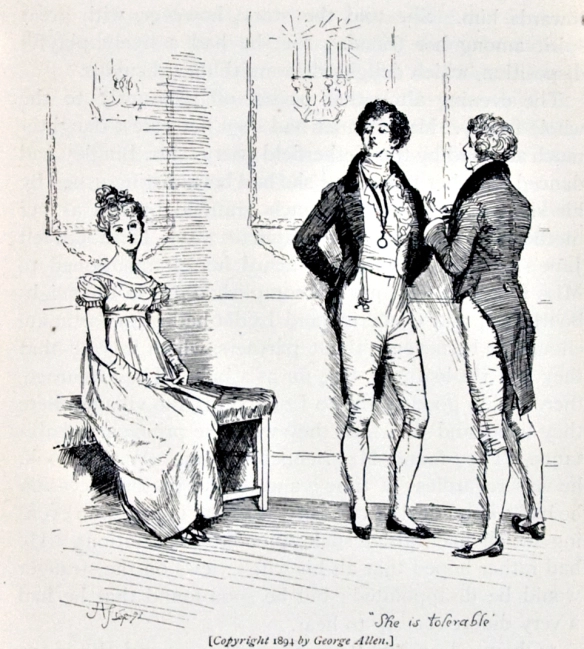

The desired object of Mrs. Bennet’s wishes at length arrives; and Mr. Bennet, though he continues to teaze his lady, by refusing to go to Netherfield, is among the first to welcome Mr. Bingley. Mrs. Bennet is delighted to find, that he not only her husband [sic] has complied with her wishes; but that Mr. Bingley is a charming handsome man, that he intends to be at the next county ball, and that he is fond of dancing, ‘which was a certain step towards falling in love.’ At the ball her raptures know no bounds, when Mr. Bingley evidently gives the preference to her eldest daughter before any lady in the room by dancing twice with her in the course of the evening. This is not all; for Mr. Bingley, according to the wishes and desires of Mrs. Bennet, does really and truly fall in love with the beautiful and amiable Jane. Mr. Bingley is, however, prevented from making his proposals of marriage by the interference of his friend, Mr. Darcy, a man of high birth and great fortune. Mr. Darcy represents to his friend the disgrace not only of being allied to a family, who had relations in trade, but particularly where the chief members of it were so wanting in the common forms of decorum and propriety as Mrs. Bennet and her younger daughters were. Mr. Bingley has great respect for his friend’s judgment; and, being given to understand, that Jane did not return his passion, absents himself from Netherfield, and leaves Jane to wear the willow.

Mr. Darcy, who has, in his manners, the greatest reserve and hauteur, and a prodigious quantity of family pride, becomes, in spite of his determination to the contrary, captivated with the lively and sensible Elizabeth; who, thinking him the proudest of his species, takes great delight in playing the Beatrice upon him; and, finding his manners so very unbending, sets him down as a most disagreeable man. This dislike is heightened almost into hate by her being made acquainted with the part which he took in separating Mr. Bingley from her sister. She is also prejudiced against him for some cruel conduct, of which she believes him guilty towards a young man who was left to his protection. Whilst thinking of him with great bitterness and dislike, and believing herself also to be equally disliked in turn by him, she is surprised by a visit from Mr. Darcy, who formally declares himself her admirer. This gentleman, at the same time, owns, that his pride was hurt by the contemplation of her inferiority; and he acknowledges, that he loves her against his will, his reason, and even his character. This provocation, aided by her fixed dislike, makes her refuse him with very little ceremony. Darcy is highly offended; and, during their conversation, Elizabeth upbraids him for his conduct towards her sister, in separating her from Mr. Bingley. She accuses him also of having, in defiance of honour and humanity, ruined the immediate prosperity, and blasted the prospects of the young man who was left under his protection. Darcy parts from her in anger, and Elizabeth retains her abhorrence of his character.

The next day comes an explanation in a letter of Darcy’s conduct, which so entirely exculpates him from the crimes which have been alleged against him, and to which Elizabeth had given credit, that she is obliged to condemn herself for her precipitancy in believing the calumnies to which she had given ear, and exclaims:

‘How despicably have I acted! I who have valued myself on my abilities! who have often disdained the generous candour of my sister, and gratified my vanity in useless or blameable distrust.’

From this moment, Elizabeth’s prejudice and dislike gradually subside; and the sly little god shoots one of his sharpest arrows very dexterously into her heart. On the character of Elizabeth, the main interest of the novel depends; and the fair author has shewn considerable ingenuity in the mode of bringing about the final eclaircissment between her and Darcy. Elizabeth’s sense and conduct are of a superior order to those of the common heroines of novels. From her independence of character, which is kept within the proper line of decorum, and her well-timed sprightliness, she teaches the man of Family-Pride to know himself. He owns:

‘I have been a selfish being all my life, in practice, though not in principle. As a child, I was taught what was right: but I was not taught to correct my temper. I was given good principles, but left to follow them in pride and conceit. Unfortunately, an only son (for many years an only child), I was spoilt by my parents, who, though good themselves (my father particularly, all that was benevolent and amiable), allowed, encouraged, almost taught me to be selfish and overbearing, to care for none beyond my own family circle, to think meanly of all the rest of the world, to wish at least to think meanly of their sense and worth compared with my own. Such I was, from eight to eight and twenty; and such I might have been but for you, dearest, loveliest Elizabeth! What do I not owe you! You taught me a lesson, hard indeed at first, but most advantageous. By you, I was properly humbled. I came to you without a doubt of my reception. You shewed me how insufficient were all my pretensions to please a woman worthy of being pleased.’

The above is merely the brief outline of this very agreeable novel. An excellent lesson may be learned from the elopement of Lydia:—the work also shows the folly of letting young girls have their own way, and the danger which they incur in associating with the officers, who may be quartered in or near their residence. The character of Wickham is very well pourtrayed;—we fancy, that our authoress had Joseph Surface before her eyes when she sketched it; as well as the lively Beatrice, when she drew the portrait of Elizabeth. Many such silly women as Mrs. Bennet may be found; and numerous parsons like Mr. Collins, who are every thing to every body; and servile in the extreme to their superiors. Mr. Collins is indeed a notable object.

The sentiments, which are dispersed over the work, do great credit to the sense and sensibility of the authoress. The line she draws between the prudent and the mercenary in matrimonial concerns, may be useful to our fair readers—therefore we extract the part.

‘Mrs. Gardiner then rallied her niece on Wickham’s desertion, and complimented her on bearing it so well. “But my dear Elizabeth,” she added, “what sort of a girl is Miss King? I should be sorry to think our friend mercenary.” “Pray, my dear aunt, what is the difference in matrimonial affairs, between the mercenary and the prudent motive? When does discretion end, and avarice begin? Last Christmas you were afraid of his marrying me, because it would be imprudent; and now, because he is trying to get a girl with only ten thousand pounds, you want to find out that he is mercenary.” “If you will tell me what sort of a girl Miss King is, I shall know what to think.” “She is a very good kind of girl, I believe. I know no harm of her.” “But he paid her not the smallest attention, till her grandfather’s death made her mistress of this fortune.” “No, why should he? If it was not allowable for him to gain my affections, because I had no money, what occasion could there be for making love to a girl whom he did not care about, and who was equally poor.” “But there seems indelicacy in directing his attentions towards her, so soon after this event.”

‘“A man in distressed circumstances has not time for all those elegant decorums which other people may observe. If she does not object to it, why should we?” “Her not objecting, does not justify him. It only shews her being deficient in something herself—sense or feeling.” “Well,” cried Elizabeth, “have it as you choose. He shall be mercenary and she shall be foolish,” ’ &c.

This also may serve as a specimen of the lively manner in which Elizabeth supports an argument.

We cannot conclude, without repeating our approbation of this performance, which rises very superior to any novel we have lately met with in the delineation of domestic scenes. Nor is there one character which appears flat, or obtrudes itself upon the notice of the reader with troublesome impertinence. There is not one person in the drama with whom we could readily dispense;—they have all their proper places; and fill their several stations, with great credit to themselves, and much satisfaction to the reader.