Like all self-organized, adaptive systems, society moves in nonlinear ways. Even as our civilization unravels, a new ecological worldview is spreading globally. Will it become powerful enough to avert a cataclysm? None of us knows. Perhaps the Great Transition to an ecological civilization is already under way, but we can’t see it because we’re in the middle of it. We are all co-creating the future as part of the interconnected web of collective choices each of us makes: what to ignore, what to notice, and what to do about it.

Excerpted from The Web of Meaning: Integrating Science and Traditional Wisdom to Find Our Place in the Universe (published in June in the UK, and available July 13 in the US).

The nonlinearity of history

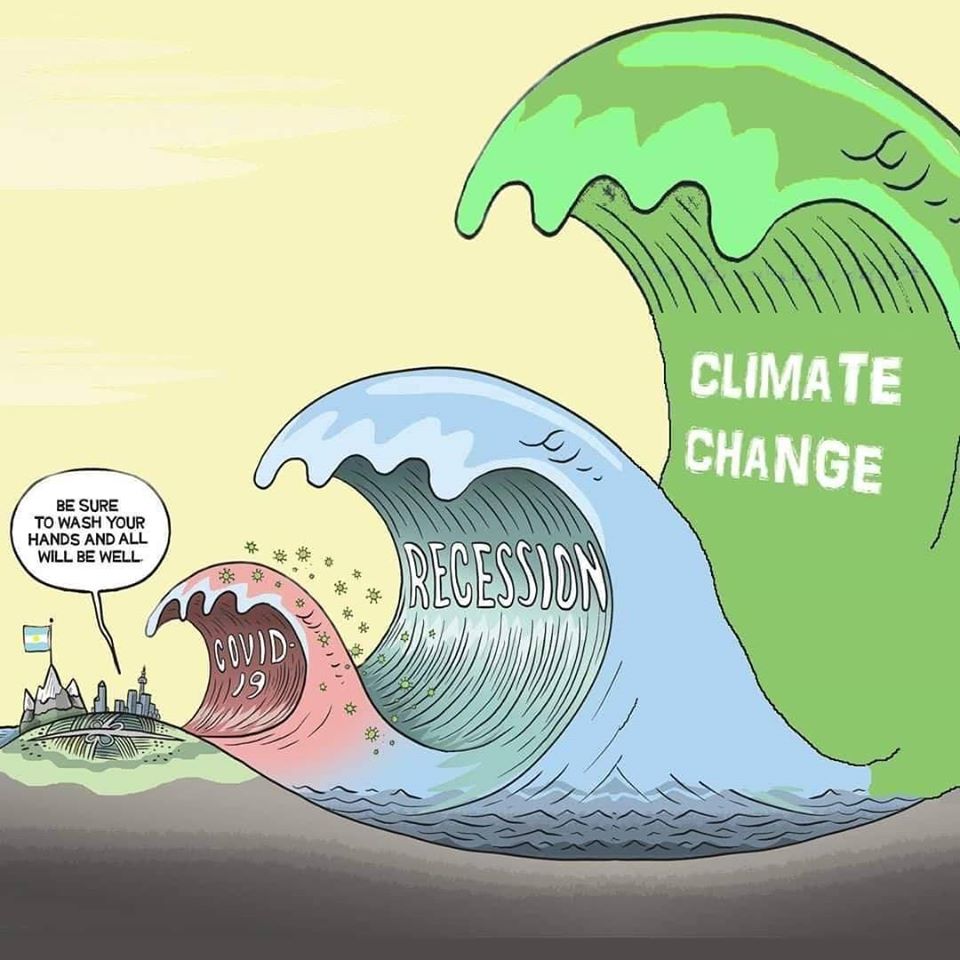

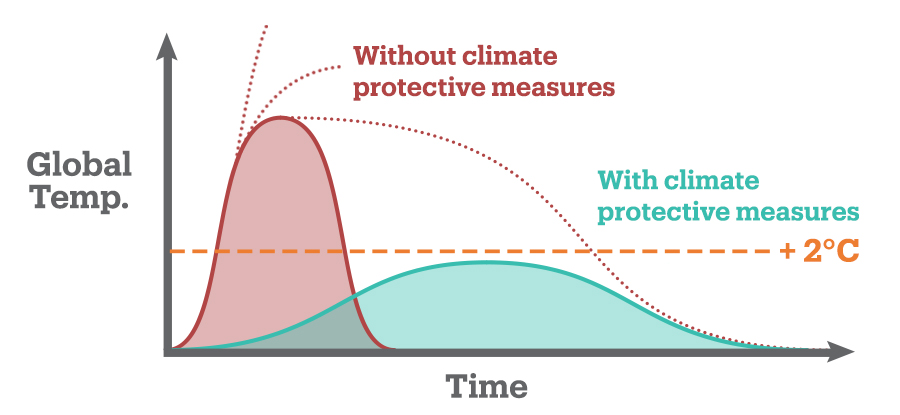

There are many good reasons to watch the unfolding catastrophe of our civilization’s accelerating drive to the precipice and believe it’s already too late. The unremitting increase in carbon emissions, the ceaseless devastation of the living Earth, the hypocrisy and corruption of our political leaders, and our corporate-owned media’s strategy of ignoring the topics that matter most to humanity’s future—all these factors come together like a seemingly unstoppable juggernaut driving our society toward breaking point. As a result, an increasing number of people are beginning to reconcile themselves to a terminal diagnosis for civilization. In the assessment of sustainability leader Jem Bendell, founder of the growing Deep Adaptation movement, we should wake up to the reality that “we face inevitable near-term societal collapse.”

Our civilization certainly appears to be undergoing profound transition. But it remains uncertain what that transition will look like, and even more obscure what new societal paradigm will re-emerge once the smoke clears. A cataclysmic collapse leaving the few survivors in a grim dark age? A Fortress Earth condemning most of humanity to a wretched struggle for subsistence while a morally bankrupt minority pursue their affluent lifestyles? Or can we retain enough of humanity’s accumulated knowledge, wisdom, and moral integrity to recreate our civilization from within, in a form that can survive the turmoil ahead?

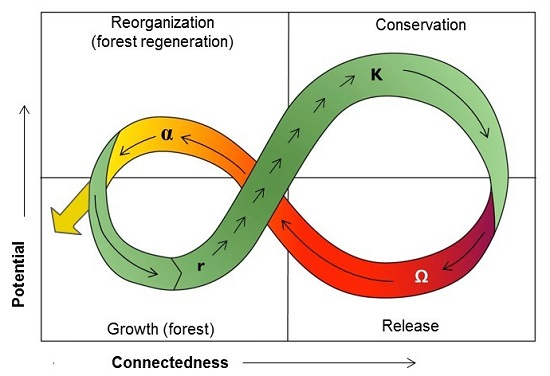

An important lesson from history is that—like all self-organized, adaptive systems—society changes in nonlinear ways. Events take unanticipated swerves that only make sense when analyzed retroactively. These can be catastrophic, such as the onset of a world war or civilizational collapse, but frequently they lead to unexpectedly positive outcomes. When a dozen or so Quakers gathered in London in 1785 to create a movement to end slavery, it would have seemed improbable that slavery would be abolished within half a century throughout the British Empire, would spur a civil war in the United States, and eventually become illegal worldwide. When Emmeline Pankhurst founded the National Union for Women’s Suffrage in 1897, it took ten years of struggle to muster a few thousand courageous women to join her on a march in London—but within a couple of decades, women were gaining the right to vote across the world.

In recent decades, history has continued to surprise those who scoff at the potential for dramatic positive change. It took eight years from Rosa Parks being arrested for refusing to give up her seat on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama, to the March on Washington where Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I have a dream” speech inspired the nation—leading to the Civil Rights Act being passed into law the following year. In 2006, civil rights activist Tarana Burke used the phrase “Me Too” to raise awareness of sexual assault; she couldn’t have known that, ten years later, it would potentiate a movement to transform abusive cultural norms.

The rise of an ecological worldview

Might people one day look back on our era and say something similar about the rise of a new ecological civilization concealed within the folds of one that was dying? A profusion of groups is already laying the groundwork for virtually all the components of a life-affirming civilization. In the United States, the visionary Climate Justice Alliance has laid out the principles for a just transition from an extractive to a regenerative economy. In Bolivia and Ecuador, traditional ecological principles of buen vivir and sumak kawsay (“good living’) are written into the constitution. In Europe, large-scale cooperatives, such as Mondragon in Spain, demonstrate that it’s possible for companies to provide effectively for human needs without utilizing a shareholder-based profit model.

Meanwhile, a new ecological worldview is spreading globally throughout cultural, political, and religious institutions, establishing common ground with Indigenous traditions that have sustained their knowledge worldwide for millennia. The core principles of an ecological civilization have already been set out in the Earth Charter—an ethical framework launched in The Hague in 2000 and endorsed by over six thousand organizations worldwide, including many governments. In China, leading thinkers espouse a New Confucianism, calling for a cosmopolitan, planetary-wide ecological approach to reintegrating humanity with nature. In 2015, Pope Francis shook the Catholic establishment by issuing his encyclical, Laudato Si’, a masterpiece of ecological philosophy that demonstrates the deep interconnectedness of all life, and calls for a rejection of the individualist, neoliberal paradigm.

Perhaps most importantly, a people’s movement for life-affirming change is spreading around the world. When Greta Thunberg skipped school in August 2018 to draw attention to the climate emergency outside the Swedish parliament, she sat alone for days. Less than a year later, over one and half million schoolchildren joined her in a worldwide protest to rouse their parents’ generation from their slumber. A month after Extinction Rebellion demonstrators closed down Central London in April 2019 to draw attention to the world’s dire plight, the UK Parliament announced a “climate emergency”—something that has now been declared by nearly two thousand jurisdictions worldwide comprising over a billion citizens. Meanwhile, a growing campaign of “Earth Protectors” is working to establish ecocide as a crime prosecutable by the International Criminal Court in The Hague.

Is this enough? Can the collective power of these movements stand up to the inexorable force of corporate capitalism that so tightly maintains its stranglehold on the political, cultural, and economic systems of the world? When we consider the immensity of the transformation needed, the odds look daunting. Those nonlinear historical shifts described earlier—while revolutionary in their own way—were ultimately absorbed into the capitalist system, which has the tenacity of the mythical multi-headed hydra. The transformation needed now requires a metamorphosis of virtually every aspect of the human experience, including our values, goals, and behavioral norms. A change of such magnitude would be an epochal event, on the scale of the Agricultural Revolution that launched civilization, or the Scientific Revolution that engendered the modern world. And in this case, we don’t have the millennia or centuries those revolutions took to unfold—this one must occur within a few decades, at most.

Is the Great Transition already under way?

Daunting, yes—but it’s too soon to say whether such a transformation is impossible. There are powerful reasons why such a drastic change could come to pass far more rapidly than many people might expect. The same tight coupling between global systems that increases the risk of civilizational collapse also facilitates the breakneck speed at which deeper, systemic changes can now occur. The world’s initial reaction to the coronavirus pandemic of 2020 showed how quickly the entire economic system can respond when a recognizably clear and present danger emerges. The vast bulk of humanity is now so tightly interconnected through the internet that a pertinent trigger—such as the horrifying spectacle of George Floyd’s murder in Minneapolis by a police officer—can set off street protests within days throughout the world.

Most importantly, as the world system begins to unravel on account of its internal failings, the strands that kept the old system tightly interconnected also get loosened. Every year that we head closer to a breakdown, as greater climate-related disasters rear up, as the outrages of racial and economic injustice become even more egregious, and as life for most people becomes increasingly intolerable, the old story loses its hold on humanity’s collective consciousness. As waves of young people come of age, they will increasingly reject what their parents’ generation told them. They will look about for a new worldview—one that makes sense of the current unraveling, one that offers them a future they can believe in. People who lived through the Industrial Revolution had no name for the changes they were undergoing—it was a century before it received its title. Perhaps the Great Transition to an ecological civilization is already under way, but we can’t see it because we’re in the middle of it.

As you weigh these issues, there is no need to decide whether to be optimistic or pessimistic. Ultimately, it’s a moot point. As author Rebecca Solnit observes, both positions merely become excuses for inaction: optimists believe things will work out fine without them; pessimists believe nothing they do can make things better. There is, however, every reason for hope—hope, not as a prognostication, but as an attitude of active engagement in co-creating that future. Hope, in the resounding words of dissident statesman Václav Havel, is “a state of mind, not a state of the world.” It is a “deep orientation of the human soul that can be held at the darkest times . . . an ability to work for something because it is good, not just because it stands a chance to succeed.”

This points to the most important characteristic of the future: it is something that we are all co-creating as part of the interconnected web of our collective thoughts, ideas, and actions. The future is not a spectator sport. It’s not something constructed by others, but by the collective choices each of us makes every day: choices of what to ignore, what to notice, and what to do about it.

Coming back to life

We live in a world designed to keep us numb—a culture spiked with innumerable doses of spiritual anesthesia concocted to bind us to the hedonic treadmill, to shuffle along with everyone else in a “consensus trance.” We are conditioned from early infancy to become zombie agents of our growth-based capitalist system—to find our appropriate role as consumer, enforcer, or sacrificial victim, as the case may be, and exhaust our energy to expedite its goal of sucking the life out of our humanity and nature’s abundance.

But, powerful as its hold is, we have the potential to shed our cultural conditioning. As we learn to open our eyes that have been sealed shut by our dominant culture, we can discern the meaning that was always there waiting for us. We can awaken to our true nature as humans on this Earth, feel the life within ourselves that we share with all other beings, and recognize our common identity as a moral community asserting the primacy of core human values. As we open awareness to our interbeing, our ecological self, we can experience ourselves as “life that wills to live in the midst of life that wills to live”—and realize the deep purpose of our existence on Earth to tend Gaia and participate fully in its ancient, sacred insurgence against the forces of entropy.

There are many effective methods to shed the layers of conditioning. Each person’s pathway is unique. Some choose extended time in nature; others may utilize psychedelic insights, learn from Indigenous groups, engage in meditation or embodied practices, or simply open up to the deep animate nature within themselves. The trail has already been blazed by those who have assumed their sacred responsibilities and developed on-ramps for others in their wake. Ecophilosopher Joanna Macy, for example, has developed a set of transformative practices, called The Work that Reconnects, offered in communities worldwide, that helps people navigate the steps of what she calls “coming back to life.” Beginning with gratitude, it spirals into a full acceptance of the Earth’s heartbreak—the willingness, in Thích Nhât Hanh’s words, “to hear within us the sounds of the Earth crying.”

Absorbing this pain, however, doesn’t mean wallowing in it. Rather than giving way to despair, it instead becomes a springboard to action. As such, The Work that Reconnects leads its participants to experience the deep interconnectedness of all things, and continue the spiral into conscious, active engagement. As Neo-Confucian philosopher Wang Yangming noted: “There have never been people who know but do not act. Those who are supposed to know but do not act simply do not yet know.” You know when you’ve reached the place of fully experiencing the Earth’s heartbreak, because you suddenly realize you are drawn to action—not because you think you should do something, but because you are impelled to do it.

Explore The Web of Meaning further on Jeremy Lent’s website. The book is now available for purchase in the UK and in the USA/Canada.