The most recent collection of short stories by Vladimir Nabokov, incorporating thirteen new stories, was published in 2008 to great fanfare. I’m just getting around to reading it now, because it usually takes me about ten years to catch up with major literary events; plus, I can’t exactly say I was a fan of this particular writer up till now. We’ll see.

Nabokov is widely known as having been a Blackwing enthusiast, and indeed his lifespan seems to have coincided with the glory days of the pencil in general. The humble instrument makes several appearances in his fiction, including the now almost-defunct indelible pencil. The following is from the short story “Bachmann,” about an egotistical musical genius of that name:

Bachmann was sitting on her bed, barefoot and in a nightshirt, with a plaid blanket humped over his shoulders. He was drumming with two fingers on the marble top of the night table, while using his other hand to make dots on a sheet of music paper with an indelible pencil.

After a memorable night, during which Bachmann’s mistress succumbs to a fatal illness, his agent inspects the aftermath:

On the night table Sack found a crumpled sheet of music paper, but no one was able to decipher the violet dots of music scattered over it.

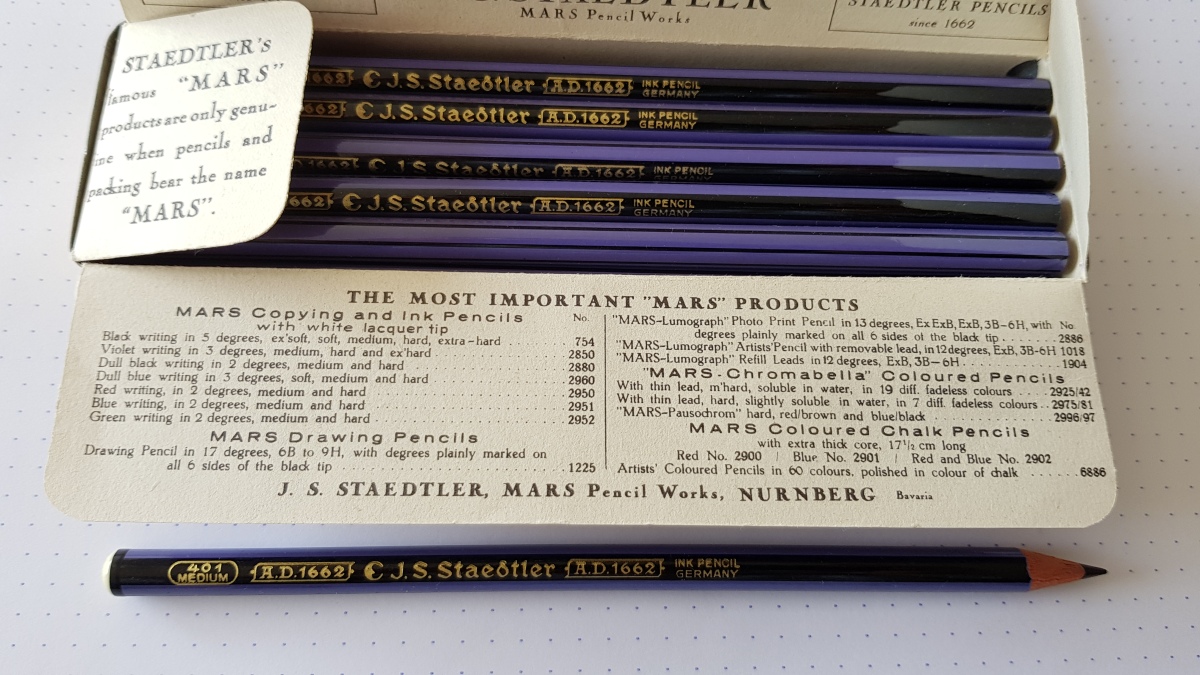

I wonder how many modern readers will understand why the markings are “violet”? (And here I’m thankful for my crash course in pencil history over the past few years!) For my part I am curious whether Bachmann used a violet-colored indelible pencil, or used a moistened graphite one. I’d wager the latter – you’re not supposed to suck on indelible pencils because the aniline dye is poisonous, but I wouldn’t put it past any deranged artists.

(If you are unfamiliar with indelible/copying/ink pencils, you can start here, at Pencil Talk.)