One hundred and two years ago Virginia Rappe died in a private hospital in San Francisco. The following passages are from our work-in-progress to mark this occasion.

The decision to send Rappe to the Wakefield Sanitarium at 1065 Sutter Street, six blocks from the St. Francis Hotel, has long been seen as suspect in earlier narratives. David Yallop, in breathless italics, called Wakefield a “maternity hospital” to support his assertion that Rappe had come to San Francisco for an abortion and her chance meeting with Arbuckle at his Labor Day party was only an opportunity to beg money from him to pay for it. Greg Merritt has a less sensational take. In his book, the hospital’s owner and founder, Dr. W. Francis Wakefield, was a specialist in obstetrics, gynecology, and high-risk births, whose hospital was inappropriate for a case like Rappe. Most other writers either echo these assumptions or embellish them, describing the Wakefield Sanitarium as a glorified abortion clinic for wealthy society women and not even a legitimate hospital.[1]

But there is no evidence for the Wakefield being anything other than a forty-bed private general hospital as it was listed in The American Hospital Digest and Directory throughout its history. Newspaper articles, scholarly journal entries, and obituaries from the 1900s onward reveal much the same as does Dr. Wakefield’s career as a surgeon and his proprietorship of the Wakefield Sanitarium in San Francisco. Furthermore, the hospital served both male and female patients and wealth and status weren’t criteria for admission or treatment.

The Wakefield Sanitarium was originally located at 767 Sutter Street. In 1912, the hospital moved into a new building at the southeast corner of Hyde and Post streets. In 1917, Dr. Wakefield took over the Anderson Sanitarium at 1065 Sutter and relocated his hospital there. Although women certainly had caesarian operations there, such operations at the time required a longer convalescence due to the danger of infection. This was the same for any patient getting surgery prior to antibiotics and—with the advent of automobiles and the increasing number of traffic accidents, the Wakefield became the hospital for trauma patients, able to provide heroic measures in the operating room, such as emergency amputations, when necessary. The Wakefield, being a private hospital, also served a clientele who could afford a level of attention and comfort that was greater than would have been available at the larger city hospitals. Dr. Wakefield understood the value of such institutions at the time, for his patients were often among his social set.

Dr. Wakefield, a Canadian immigrant in his early fifties, had risen to prominence in San Francisco society during the 1910s and ’20s. Though he was known among the public for hosting social events with his wife, a more select group of people knew he also performed abortions. Though they were illegal, in virtually every American city, some of the most upstanding doctors provided abortions but only under the most discreet terms and calling the surgeries something else for the hospital chart. In other words, an unknown woman from Los Angeles couldn’t just check in and get a safe abortion in a San Francisco hospital and go home. Rappe’s willingness to attend Arbuckle’s party should dismiss any thought of her keeping an appointment with an abortionist.

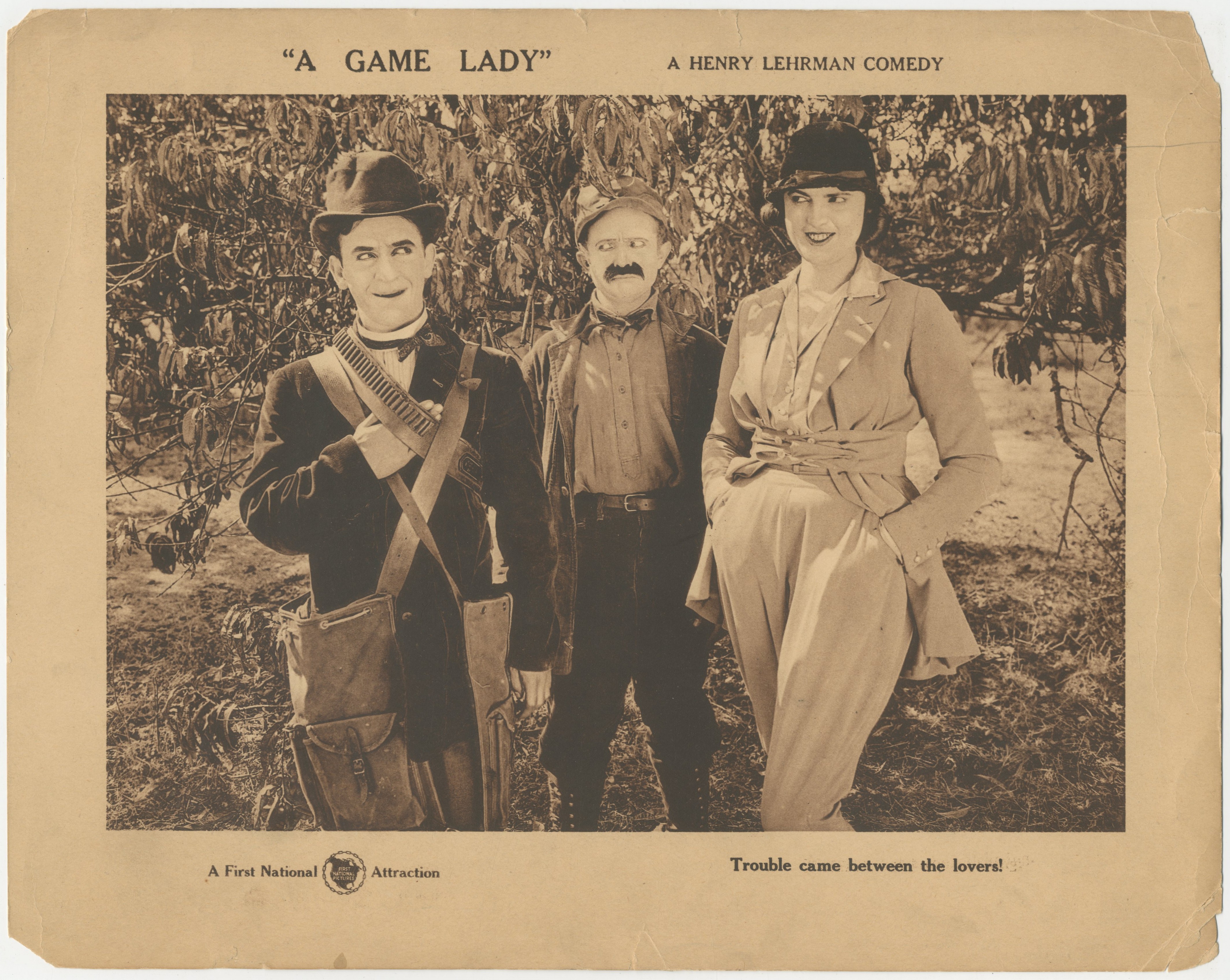

Dr. Rumwell, the house doctor at the St. Francis Hotel, was a friend of Dr. Wakefield and had performed operations in his hospitals. Rumwell’s criteria for sending Rappe to the Wakefield Sanitarium would seem in hindsight to be in his patient’s best interests, in terms of discretion. She—and Delmont—didn’t want any publicity that might embarrass or anger Arbuckle (or Lehrman) and then refuse to foot the bill. Beat reporters frequented the public hospitals looking for the victims of accidents and crimes and they had informants in the emergency wards and staff. A private hospital, on the other hand, could protect a patient’s privacy. Out of respect for Maude Delmont’s requests, Rumwell had gone against his own judgment and allowed Rappe to lie in agony in a hotel bed for days—until her condition was so obviously life-threatening that rushing her to a hospital was the only option.

Rumwell initial diagnosis of acute alcoholism had been proven grossly inaccurate as the symptoms of a massive internal infection became obvious. His misdiagnosis and the time he spent adhering to it, foretold a grim outcome.

If there was hope, the Wakefield had two operating theaters. If anything went amiss, Rumwell himself could better keep it under wraps at the Wakefield, if for no other reason than to protect his reputation.

While the Wakefield’s patient, Rappe wasn’t given a celiotomy or any other invasive procedure that might have revealed her condition. Instead, she was given morphine, provided with a private room, and left under the care of Maude Delmont and two hired nurses.

At 7:00 p.m., Thursday evening, September 8, Nurse Cumberland relieved Nurse Jameson for what was scheduled to be a twelve-hour shift. But not long into it, Cumberland, either by telephone or in person, confronted Dr. Rumwell. She told him Rappe’s case had “been handled negligently.”

“When I realized the circumstances of the case,” she said to the press, “I had visions of juries, judges, investigators, and policemen. It was disgusting. Finally, I determined that the fair name of Cumberland should not be dragged into the filth of actors’ misdoings, so I requested my release.”

Cumberland had a high opinion of her social importance. She had made a habit of mentioning that she was a descendant of Queen Victoria. This assertion quickly disappeared from the reportage though, perhaps because reporters had consulted Debrett’s Peerage and discovered no links to either Queen Victoria or her German cousin, the Duke of Brunswick, who also held the title of Duke of Cumberland.

In any case, what Cumberland said to Dr. Rumwell about legal implications was taken to heart. Not long after she resigned, he called in two of his colleagues at Stanford to hear him out about patient Rappe and help him decide if surgery was still an option.

Dr. Emmet Rixford had been one of Rumwell’s professors at the Cooper Medical College. The fifty-six-year-old was a specialist in the surgery of the abdomen and a polymath with expertise in horticulture, wine-making, sailing, mountain-climbing, and snails.

“Surgery,” according to Rixford in a speech in support of animal experimentation, “is not perfect and no one knows its deficiencies so well as the surgeon.” The Great War had made this all the more evident with injuries resulting in gas gangrene, necrosis, sepsis, toxemia, shock, and death. Thus, he believed, “in some sense surgery may be said to be only in its infancy.” Although anti-streptococcus and anti-staphylococcus serums were available, they were experimental and did little good. Indeed, the antibiotics that could have helped Rappe were years away.

Rixford either heard or saw for himself that her abdomen was distended, which indicated that peritonitis had set in. Although that wasn’t conclusive proof of an abscess forming around her liver, it was an added complication to any invasive surgery for which the risk of failure was considerable.

Rumwell also consulted with another colleague, Dr. W. P. Read, an associate professor of surgery at Cooper. He agreed with Rixford. Rappe was likely too far gone. That said, cases of heroic surgery had been performed in the past with the presence of peritonitis. Dr. Rixford knew of a child’s burst appendix having been successfully repaired. And he and he and his colleagues should have known that the management of acute peritonitis was an established routine, one for which Dr. Wakefield’s hospital was fully equipped, with a modern operating theater, a steam autoclave, nickel-plated instruments, and clean white and green enamelware fixtures.

The surgeon and attendants would follow the Crile forceps method—with nitrous oxide anesthesia for the duration of the surgery, local anesthesia at the point of incision, a clean-cut wound for access, adequate drainage, hot flannel packs placed over the entire abdomen and along the bedline, Fowler’s position throughout, and a Murphy’s drip in the rectum to supply the body with fluids (water, sodium bicarbonate, and glucose).

The Murphy’s drip is de rigueur for treating peritonitis even before surgery. And it was used on Rappe during her final twelve hours as though surgery had been contemplated. Tragically, however, Dr. Rumwell would need to start the drip immediately once he diagnosed peritonitis and that came too late. The time it took him to disabuse himself of his original diagnosis of alcoholism would prove dire and significantly decrease Rappe’s chances of survival.

The morphine injections given to Rappe in the hospital should have slowed down the peristaltic motion of her intestines and may have limited the spread of the disease. But large doses of morphine had a deleterious effect on the patient’s respiration and ability to respond—and this also ruled out anything like the high-risk last-resort surgery that might save a life. Over the course of Thursday and into early Friday morning, Dr. Rumwell had more reasons to talk himself out of doing so.

At such a late hour, and with no one to assist in such a futile operation, the patient, “Miss Rappe” was a lost cause.

Maude Delmont faced the prospect of no money for Rappe’s hospital bill. Neither Al Semnacher nor Roscoe Arbuckle had yet to make any arrangements for paying for the doctors and nurses and Delmont’s extended stay in San Francisco. They may not have been aware of this expectation. But it wasn’t hard to intuit that Delmont was in dire straits and had been left holding the bag.

Eventually, she turned to the one person of means who might help. She telephoned Sidi Spreckels on the morning of September 9 and told her of Rappe’s suffering and how Arbuckle was the cause.

Although she acknowledged getting Rappe’s telephone call from Arbuckle’s suite, Spreckels knew getting herself involved with motion picture people risked adding to her own unwelcome notoriety. She could ill afford that. After all, she had to look upright for herself and her daughter if she expected to get anything from her late husband’s estate. (She was vying with the first Mrs. Jack Spreckels, whose current married name was, curiously, Mrs. Wakefield.)

Initially, Spreckels told reporters she only knew Virginia Rappe “casually” and through Henry Lehrman, whom she and her late husband knew better. Even so, Spreckels agreed to act as intermediary and inform Lehrman of the situation. He was the closest person to any next of kin beside the impecunious Hardebecks. She took down the message Delmont wanted convey, especially in regard to money, and wired Lehrman.

How Spreckels knew where to send her telegraph deserves an answer. It would measure at least some of the real distance between Rappe and Lehrman in September 1921. Was he still a part of her life? Was her presence in San Francisco not a surprise, her being with Arbuckle as some in the film colony believed? In any event, Delmont knew where to find Lehrman from her own source or Rappe herself.

While waiting for Lehrman to reply, Spreckels felt a “sympathetic impulse” to do more, to see Rappe, “to be bedside of a dying acquaintance [. . .] to aid a girl dying alone in a big city with but one friend beside her, devoted as she might be”—meaning Delmont rather than herself.

Spreckels arrived at the hospital around 9:30 a.m. and discussed Rappe’s condition with Delmont and Jean Jameson. Then she turned her attention to the patient and readily saw the extent of Rappe’s decline. She looked doomed to her. Rappe’s eyes were livid, as though staring into space. She seemed not to recognize her friend.

She never knew I was there, but I stayed. It was terrible—that poor girl lying there without a friend except myself. She must have read that I was in San Francisco and her poor mind flew out to the only friend she knew.

I never intended to say a word about my visit to Miss Rappe, feeling everything would be misunderstood by the unthinking and distorted by my enemies. Why is it that a woman must have enemies? Miss Rappe, as I have always said, was a good girl—a girl that always appealed to everyone as a good clean liver.

I used to say to her that she could not have the wonderful complexion she had and dissipate, and it was so. Miss Rappe never told me a thing—she could not talk. She was too far gone for that. My only regret was that she did not know me.

Rappe, however, wasn’t as mute as Spreckels let on. In the same interview, she remembered her friend expressing a certain regret over what had happened.

“Oh, to think that I had led such a quiet life,” Rappe moaned, “and to think that I should get into such a party.”

After seeing Rappe still alive, but with no attending physician present, Sidi Spreckels stayed briefly. Then she departed to call her own physician, Dr. H. Edward Castle, a surgeon, and arranged to have him meet her back at the Wakefield. She also received a wire from Henry Lehrman addressed to “Virginia” and filled with assurances of his undying devotion. Lastly, Spreckels called her minister at the First Congregationalist Church, the Rev. James L. Gordon. She asked him to hurry and pray over her.

Hurrying back to the Wakefield Clinic, Spreckels found Rappe unconscious. But this didn’t prevent her from whispering Lehrman’s endearments into her friend’s ear.

A short time later, Rappe passed away a little after 1 o’clock in the afternoon. Dr. Castle arrived a minute after she had stopped breathing. Rev. Gordon also arrived too late. Presumably, he took the opportunity to pray anyway—for Rappe’s soul.

When Dr. Rumwell found his patient dead in her room, he was confronted by Delmont and Spreckels. They demanded that an autopsy be performed on Rappe’s body to rule out foul play. At first, Rumwell resisted and attributed Rappe’s death to natural causes. He admitted Rappe’s body bore obvious bruises. But these could have been from being handled at the hotel, lifted on and off the gurney, and other easily explained reasons. An autopsy, as he knew, could invite a criminal investigation. But given that Delmont, Spreckels, and the attending nurses were saying Rappe implicated Arbuckle, not performing an autopsy would be equally hazardous.

With such leverage in his face, Rumwell relented. He telephoned the San Francisco County Coroner, Dr. Thomas B. W. Leland, who would need to approve the autopsy. Leland would also ask questions about the patient and be obligated to initiate a criminal investigation if the evidence suggested foul play. Rumwell and Leland were friendly, having volunteered together in an effort to treat the city’s drug addicts and create a special hospital for them.

But the Coroner’s office informed Rumwell that Leland was on Naval Reserve duty in Santa Cruz. Without a coroner or chief medical examiner, a legal autopsy couldn’t be performed, but Delmont and Spreckels pressured Rumwell to find an alternative. Spreckels social standing may have played a role in making this happen though it’s also possible Delmont’s relationship with Rumwell made the difference.

Rumwell decided he couldn’t accurately fill out Rappe’s death certificate without knowing how she really died yet he undoubtedly understood the risk to his career if he ignored the legal protocol. So, he telephoned another colleague at Stanford, a man with a certain eminence. enough to impress Coroner Leland, namely the Dean of the Medical College and Professor of Pathology, Dr. William Ophuls.

Dr. Ophuls, a naturalized American citizen had been born and educated in Germany. His many degrees and honors, along with his quiet German accent underscored his authority and expertise. Ophuls agreed to conduct the autopsy. As for Rumwell, he didn’t have to assist or even watch. He only needed to accept the official responsibility.

After Dr. Ophuls arrived, two Wakefield duty nurses, Grace Halston and Margaret Forte, lifted Rappe’s body from a gurney to a cast-iron enamel table in one of the operating theaters. Halston, although still a nursing student, had gained experience assisting her physician uncle at a hospital in El Paso. She remained behind to help Dr. Ophuls manipulate Rappe’s limbs and torso. There followed a standard autopsy, with a long incision beginning just under the sternum.

A copious amount of fluid gushed from Rappe’s abdomen. When the flaps of her abdomen were moved aside, a sac of pus was found that released a noticeably foul odor. The items of greatest interest, the stomach and bladder, were examined in situ and, to facilitate this, the uterus and colon were removed and preserved in sealed specimen jars. The bladder had a pronounced tear in its crown and the peritoneum was inflamed from a massive infection.

Rappe’s body had many bruises and they caught Dr. Ophuls’ attention so he made careful notes and measurements. There followed the standard procedure of packing body cavities, where organs had been removed, with thick cotton batting. Despite being a surgeon, Dr. Ophuls could dispense with his usual care and suture up the long cavity he had made with a series of crude sutures that looked like a line of X’s running from between Rappe’s breasts to just above the pubic mound.

Finally, a shroud was drawn over the corpse and Halsted & Co., a mortuary only a block west on Sutter Street, was called.

Soon after, a black hearse arrived and the mortuary assistants took Virginia Rappe’s remains away. Once there, a blank death certificate form was started. What was obvious was entered by the same hand: Female, White, Single, with her age based on an approximate birth year of 1895, that is, Abt 25. Her occupation provided no mystery: Motion Picture Actress. Then came a series of entries that read No Record for her unknown birthplace and parentage.

“Length of Residence” was not left blank. It read “4 days.”

[1] See, for example, Paul H. Henry (1994) and J. W. Henry (2017), 000n.

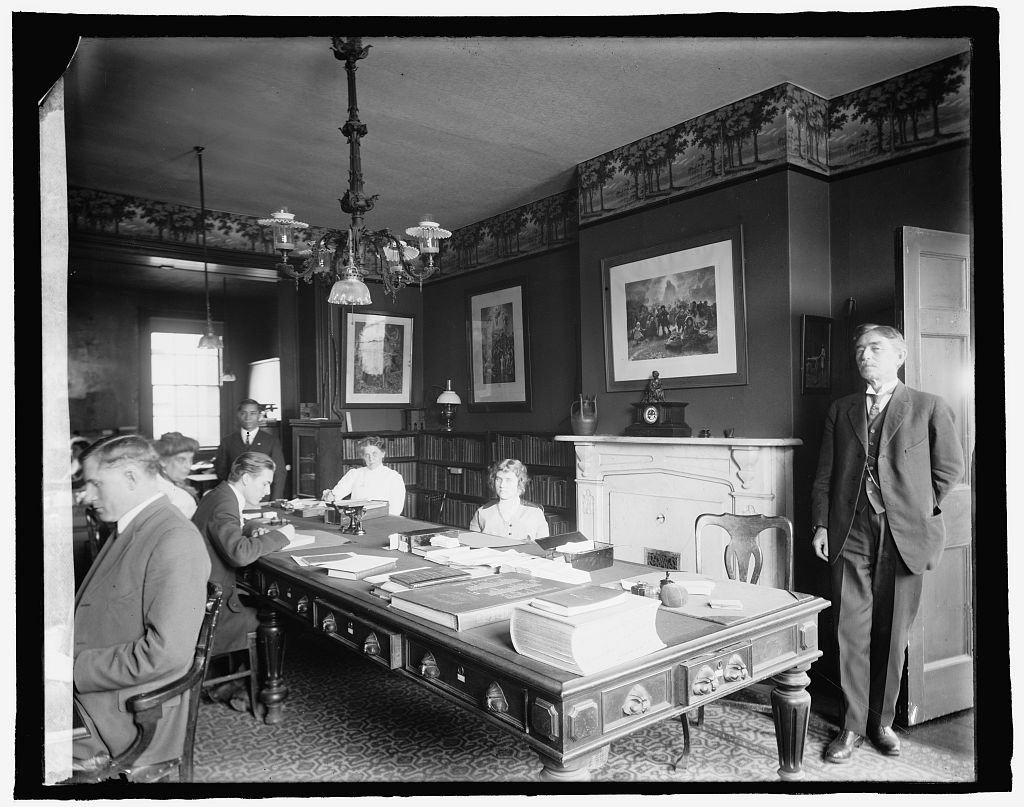

The Rev. Dr. Crafts and the staff of the International Reform Bureau. The African American man in the background ran the organization’s printing press. (Library of Congress)

The Rev. Dr. Crafts and the staff of the International Reform Bureau. The African American man in the background ran the organization’s printing press. (Library of Congress)