By Brian D’Ambrosio

Some pithy poet once said, “A man lives, he dies; he is only killed by forgetfulness.” Generals, statesmen, celebrities, sports figures, movie stars, and writers are by and large the types of characters who, for better or worse, usually keep and store well in the collective recall of public awareness. But while history records them as notable, often the communities in which they labored or lived irrespectively overlook their native yields. Many fail dismally even to remember or to recognize the value of their distinct achievements.

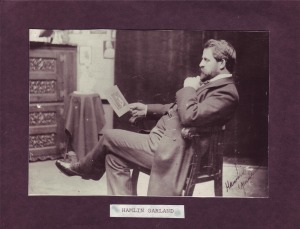

Since its beginning in 1851, West Salem, Wisconsin, has seen many noteworthy events take place and many an individual has left their mark upon the village. One of the most consequential is Hamlin Garland. To think of and to understand Garland, a prolific author and poet, it is necessary to begin by keeping in mind the forces which brought his parents to West Salem; to see his father, Richard Garland, as he pushed onward toward the goal of level, rich farmland on the expanding frontier.

It’s illuminative for us to revisit a few words of description of Wisconsin and West Salem as written by Hamlin Garland:

“My Wisconsin birthplace has always been a source of deep satisfaction to me. That a lovely valley should form the first picture in my childhood memories is a priceless endowment. It doesn’t matter so much what Green’s Coulee looks like now or what it looked like to grown-ups in 1865. It will always remain and charming and mysterious place to me

“It is still vivid in my mind. I have but to close my eyes to the present, and the tiger lilies bloom again in its meadows. The mowers toss up once more the scarlet sprays of strawberries. The blackbirds rise in clouds from out of the ripening corn. A hundred other sights and sounds, equally beautiful and equally significant, fill my inner vision.”

Born in Greenwood, Maine, on April 1, 1830, Richard Garland ran away from home to work on a railroad. Later he returned home and persuaded his parents to move westward. Arriving in Milwaukee in 1850, they started out across the promising countryside. Weeks later, they had arrived in an open meadow not far from the Mississipi River and the Minnesota border, a place called Green’s Coulee. To the east was a mill pond. A trout brook came in from the north, and a grist mill rose against a conical hill around whose base the mighty river ran in a reedy curve. On the bottom lands to the west, scattered pines were growing, and in the edges of these groves and on the banks of the stream, a group of wigwams denoted the presence of Indians. Here they laid down roots. Richard worked at various jobs, always dreaming of owning his own farm. He soon married a woman called Isabel McClintock. It was in a swatter’s cabin, half way between West Salem and the county hospital that Dr. William Hughes Stanley delivered a baby boy, christened Hamlin Garland, on September 14, 1860.

During the Civil War, Richard joined the Union army. Upon his return, the family moved westward, making their new home in Winnesheik County, Iowa, in 1868. After spending his teenage years in rural Iowa, Garland became a teacher in the Boston School of Oratory. Between the years of 1885 and 1889 he taught private classes in both English and American literature. Some time was also spent lecturing on land reform in and around Boston, where he made the acquaintance of Oliver Wendell Holmes, George Bernard Shaw, William Dean Howells, Edwin Booth and other worthies.

A trip during 1887 back to Wisconsin led him to write his Mississippi Valley stories. His impressions induced a mood of bitterness. During the weeks he worked on his father’s farm he became aware that every detail of his daily life on the farm was assuming literary significance in his mind.

“The quick callusing of my hands, the swelling of my muscles, the sweating of my scalp, all the unpleasant results of physical pain I noted down…Labor when so prolonged and severe as at this time my toil had to be is warfare…I studied the glory of the sky and the splendor of the wheat with a deepening sense of the generosity of nature and the monstrous injustice of social creeds.”

It was three years later that Main Travelled Roads was published. An instant attack was made on the book in the Midwest because it pictures the ugliness, endless drudgery and loneliness of life on a farm. Reviewers in the East, such as William Dean Howells, however, praised him.

“The stories are full of those gaunt, grim, sordid, pathetic, ferocious figures, whom our satirists find so easy to caricature as Hayseeds,” wrote Howells in Harper’s Magazine. “The type caught in Mr. Garland’s book is not pretty; it is ugly and often ridiculous; but it is heartbreaking in its rude despair.”

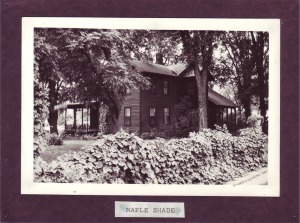

In 1891, his first novel, A Spoil of Office, was published. It was based on the political unrest in the agricultural regions of the country. The Populist movement was now in its heyday, and Hamlin’s father, Richard, was a delegate to the Omaha convention of the Populists. The winter of 1892 was spent in New York, but the following year Garland moved his headquarters to Chicago. One year later Hamlin bought his parents their first home, called the Hays house, in West Salem. It was situated on the road leading to the town of Mindoro, where so many of his mother’s family and friends lived. Built in 1857, the house was part of a wooded four acre lot, and immediately, Hamlin began enlarging it, raising the west end to the two story bay window first, tearing out the partition in the living room, putting in a furnace and bathroom. The only part left unchanged was the stairway. From 1893-1915, Garland summered here, and from 1916-1938, he extended his stays from spring till fall.

In 1912, an overheated grease fire, which started in the kitchen when the maid was lighting the fire in the oil stove to heat water for the morning washing, destroyed much of the home. But Hamlin quickly restored it. The Garlands had the first tennis court in West Salem and tennis parties were frequently held there. Named “Maple Shade” for the beautiful maple trees which shaded the kitchen and rear entry, it held tremendous views of the surrounding hills and valleys. Garland’s mother lived permanently in the house; Richard continued to spend summers in Dakota.

Hamlin’s first born, a daughter named Mary Isabel, was born in West Salem in 1903, while the second was born in Chicago in 1907. Their summers were spent in West Salem until 1915 when they began summering in the Catskill Mountains of New York. The folks of West Salem recall Garland as an eccentric and withdrawn man, as an article in the Saturday Sentinel alludes:

“The inhabitants of La Crosse County have been troubled by the fact that he writes books. From the society of these blissfully unliterary persons he departs each year into the book sets of Chicago and New York where he is more profoundly terrorized at the display of new books.

It was written that Garland might be met on the street but never acknowledged the passerby. One woman called Mrs. Tilson, who lived across the street from Garland for many years, when asked how she ever got the man to return her greeting, said that the exchange happened only because she had been “working on it for twenty years.”

It was in 1917 that A Son of the Middle Border was published. The next year, he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters, Four years hence, A Daughter of the Middle Border was published. For this novel, he was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for best biography of 1921. The University of Wisconsin gave Garland the degree of Doctor of Letters on June 21, 1926. In the bestowing this honor, Professor Frederick Paxson said: “Hamlin Garland is the novelist of our northwest farmer country. For thirty-five years his easy pen has worked at the life of our people…His writings are words of art, but they are also documents that may become the source of history…as the preserver of the fact and flavor that gave identity to the Middle Border from which we sprang.”

Garland sold Maple Shade in 1938.

In the long run every man has to shut down – Garland died in 1940 – and if he is remembered thereafter it is by the effort of others.

In 1959, Errol Kindschy was a young man, barely into his 20s, when he first saw the village of West Salem through the eyes of a fledgling social studies teacher. He had only been in the town for two weeks before the school year began, and on the first day he posed the same opening inquiry to each of the six classes he was hired to instruct.

“I asked if anybody famous was from this area,” recalls Kindschy. “For five classes, I was told quite affirmatively no. But on the last class of the day, one of the boys raised his hand, and he said that an author of some kind was from the town. He didn’t even know his name. This got me curious.”

Kindschy asked neighbors and coworkers about this famous mystery man, most of whom knew nearly nothing about the accomplished writer beyond the vague recognition of his name: Hamlin Garland.

There was one woman, however, one Rachel Gullickson, who was rather offended by Kindschy because he didn’t know the slightest bit about Garland. Not only was she familiar with Garland, a huge fan of his writing talents, but she lived in what was once his homestead.

“Gullickson moved in when Garland moved out,” said Kindschy. “This made me even more interested in Garland, and also quite interested in the fact that no history of West Salem had ever been written. When the Garland homestead came up for sale in 1972, I bought it, restored it, formed the West Salem Historical Society, and resold it to the society at a low rate.”

And though a bit run down and neglected at the time of the purchase, Kindschy saw a glimmer of a forgotten world. He understood that a single house may have only limited architectural significance, but the former residence of a great writer makes an indelible impression.

Thanks to Wisconsin Historical Society funds, donations and volunteer muscle, the Hamlin Garland Homestead was restored to the period of 1912 to 1915. The restoration of the Garland Homestead, which neatly reversed the structure from a jumbled three apartment subdivide, started in 1974, and concluded two years later, opening to the public on July 4, 1976.

“It’s been more than 30 years and most of Wisconsin still doesn’t know we are here,” says Kindschy.

Kindschy wants to push forward nevertheless. He intends to translate some of Garland’s better material into German and Japanese himself. Plus, he still has ample material from Garland’s extensive catalogue to get acquainted with.

“I’ve read thirty-eight out of the fifty-two books Garland wrote,” says Kindschy. “And, honestly, some of them I wish I never picked up, and some of them are fantastic. Main Travelled Roads and Trailmakers, which is the story of the Garlands coming into this area, are my favorites.”

“Somewhere in Garland’s life,” he continues, “he discovered that all the books he was reading had happy endings. He didn’t like this. In my opinion, he became the first American realist, Jack London and others followed. In his lifetime, he was known as a controversial dean of American Literature. I’ve dug up old newspaper articles in which he was booed off the stage here in West Salem at the old settlers’ meeting, and booed off the stage at the University of Madison, for supporting American Indians and women’s independence and education, promoting the occult and séances, and proposing a single tax system.”

Kindschy and I tour Garland’s study, which includes his rocker, desk, movie projector, ink wells, pictures, and books. It’s one of the most evocative rooms in the house, silent and peaceful, with Garland’s own card table and playing cards, and a bookcase of his original books, many autographed to members of his family or friends.

It’s Kindschy’s favorite room – and it shows in his keenness. I never saw any one so feverishly alive as this little, old man this room, his bright, withered cheeks, over which the skin was drawn tightly, his darting eyes, under their prickly bushes of eyebrow, his fantastically-creased white and gold curls of hair, his subtle mouth, and, above all, his hands, never at rest. His fingers are short, tight, bony, wrinkled, with every finger alive at the tips, like the fingers of a mesmerist. His hands are never out of his sight, they travel to his nose, crawled all over his face, and grimace in little gestures.

“Garland had an indoor bathroom and tennis court and lawn mower,” says Kindschy, pointing to the back yard. “So people thought he was putting on heirs. He wouldn’t converse with the local people at all. His short stories were thought to have portrayed some of the local Germans in a negative light. He described them as he saw them, I guess. They wanted to talk about family and farming, he wanted to talk about literature and books. Those farmers, they didn’t see his work as a writer.”

One hour or so later, we are back downstairs in the museum room, which includes Garland’s actual Pulitzer Prize, his original book illustrations, first editions, family photos, letters, autographs, cards, and poems, all of which have been collected by Kindschy over time.

“One time I was playing Hamlin Garland,” says Kindschy, flipping through a scrapbook of Garland-related press clippings. “And this 80-year-old woman came up to me and said ‘do you remember when I brought cookies to your house? I knocked on your door, and you asked me what I wanted, grabbed the plate, said thanks, and slammed the door. I cried all the way home. She must have thought I was Garland.”

As we exit the museum room and prepare to return to the vagaries of the banal, comparatively dull world outside, Kindschy speculates on the long-term fate of Garland’s writings, which he thinks might someday have a revival. A revival he hopes to spark with a blitzkrieg of Garland events scheduled to coincide with the one-hundred and fifty year anniversary of his birth in September.

During a brief interlude in the conversation, I tell Kindschy how much I appreciate all that he has done to preserve and enhance a deference that transcends a single, tangible structure, and that stimulates symbolic, hopeful feelings drawn from the desire to learn our cultural heritage.

Seemingly quite touched, he clicks off the lights, grins affectionately, takes a deep breath, and says, “I am proud of what I have been able to do to contribute to the recognition of Hamlin Garland.”

To read more of Brian D’Ambrosio’s Wisconsin art, history, and travel articles.