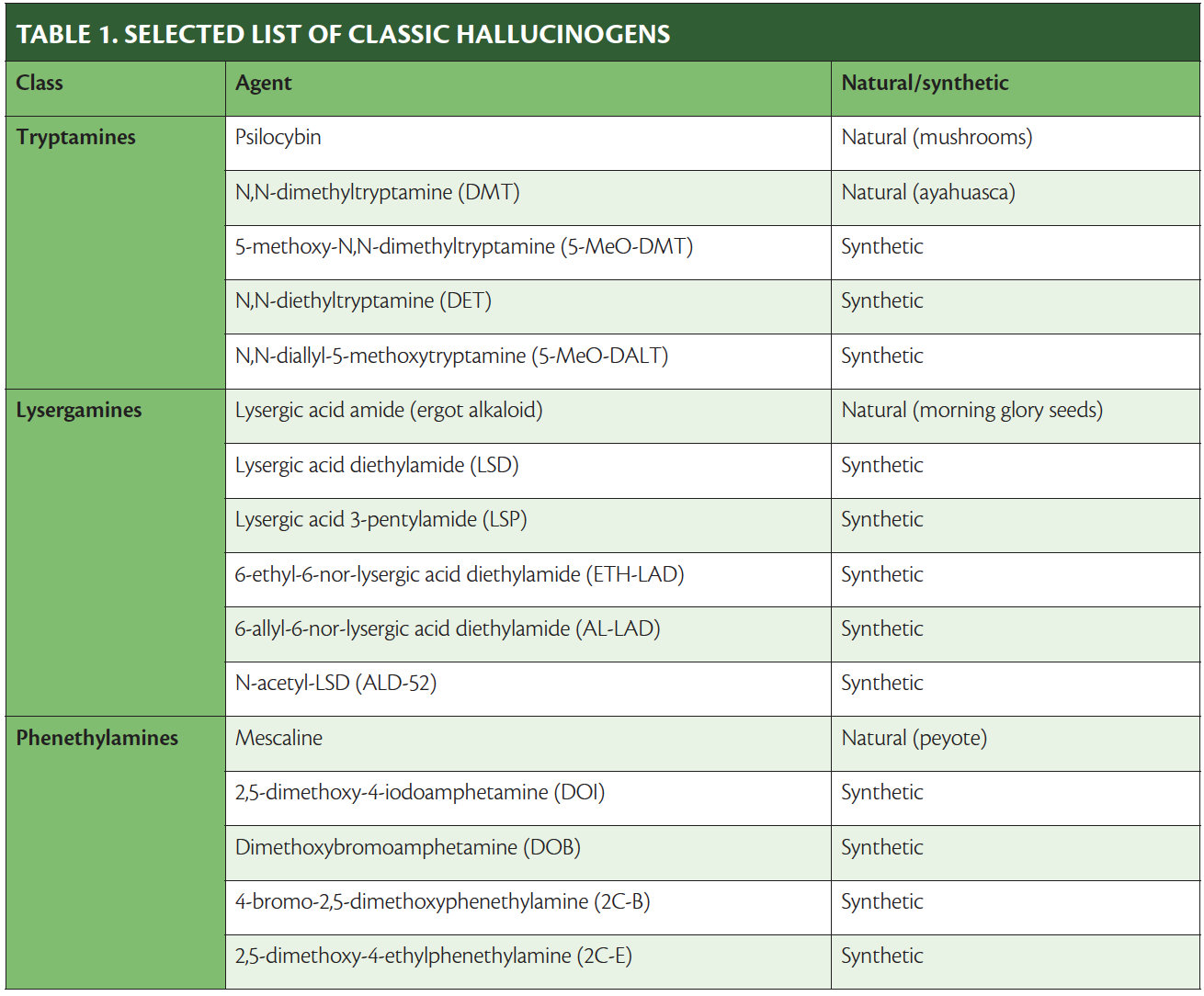

Hallucinogens have been defined as drugs that produce changes in mood, thought, and perception, with little memory or intellectual impairment; cause little or no stupor, narcosis, stimulant effects, or autonomic effects; and are not addictive (ie, do not cause physical dependence).1 The classic hallucinogens (Table 1) are further defined as hallucinogens that bind to the 5-HT2 serotonin receptor and can be differentiated by animals trained to discriminate them from the substituted amphetamine 2,5-dimethoxy-4-methylamphetamine (DOM). Classic hallucinogens are commonly called psychedelics because of the “mind-manifesting” effects they produce. Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), psilocybin (mushrooms), and mescaline (peyote) are among the most well-known of these agents.2,3 Tolerance to hallucinogens develops rapidly, such that by the fourth day of consistent use, hallucinations no longer occur.

Although classic hallucinogens are scheduled by the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) as Schedule I—having no medicinal use and high abuse potential4—by definition, use does not cause physical dependence. Thus, the DEA classification effectively means that use for any reason at any dose is legally considered “drug abuse” or substance-use disorder. The rationality of this approach is left to the reader to consider.

Classic Hallucinogens and Cluster Headache

Use of classic hallucinogens, or psychedelics, for cluster headache gained recognition in the late 1990s, when a person in Scotland wrote on an Internet forum that his cluster headache had not come back as usual and might be due to his recreational use of hallucinogens: first LSD and then psilocybin. Although this report was met with skepticism, some people with chronic or very frequent cluster headache began to consider using these agents. In the following years, use of psychedelics to treat cluster headache gained wider traction. In North America, Bob Wold (see Advocacy for Medicinal Use of Controlled Substances in this issue) picked up on the treatment, found it useful, and created the patient advocacy group Clusterbusters to disseminate what he had learned and help others benefit from his findings.

In 2006, a survey study of 53 people with cluster headache who had used LSD or psilocybin to treat their cluster headache was published in Neurology.5 Although survey studies are not able to prove efficacy, the study was intriguing; individuals were reported to have complete relief for weeks, often with a few uses over 1 to 2 weeks followed by several weeks without any use of hallucinogens.

Interest in use of hallucinogens continued to increase and by 2010, I was treating several individuals with cluster headache who asked about hallucinogens as potential treatment. This led me to become involved with Clusterbusters and to learn that remission of cluster headache attacks—a remission that lasted for weeks or months after use of hallucinogens—was common.

What Evidence Is There?

Because the illegal status of classic hallucinogens has prevented the performance of randomized placebo-controlled trials of their use for any condition and there are no animal models of cluster headache, the only data available for these agents are from studies of real-world use among people willing to risk the legal consequences of use. Further complicating the quest for evidence of efficacy for cluster headache is the subjective nature of headache disorder symptoms and the high rates of placebo effect. Cluster headache, however, is somewhat easier to evaluate than other headache disorders because cluster headache is inherently severe; therefore, determining the existence of cluster headache can be based on a simple yes or no question.

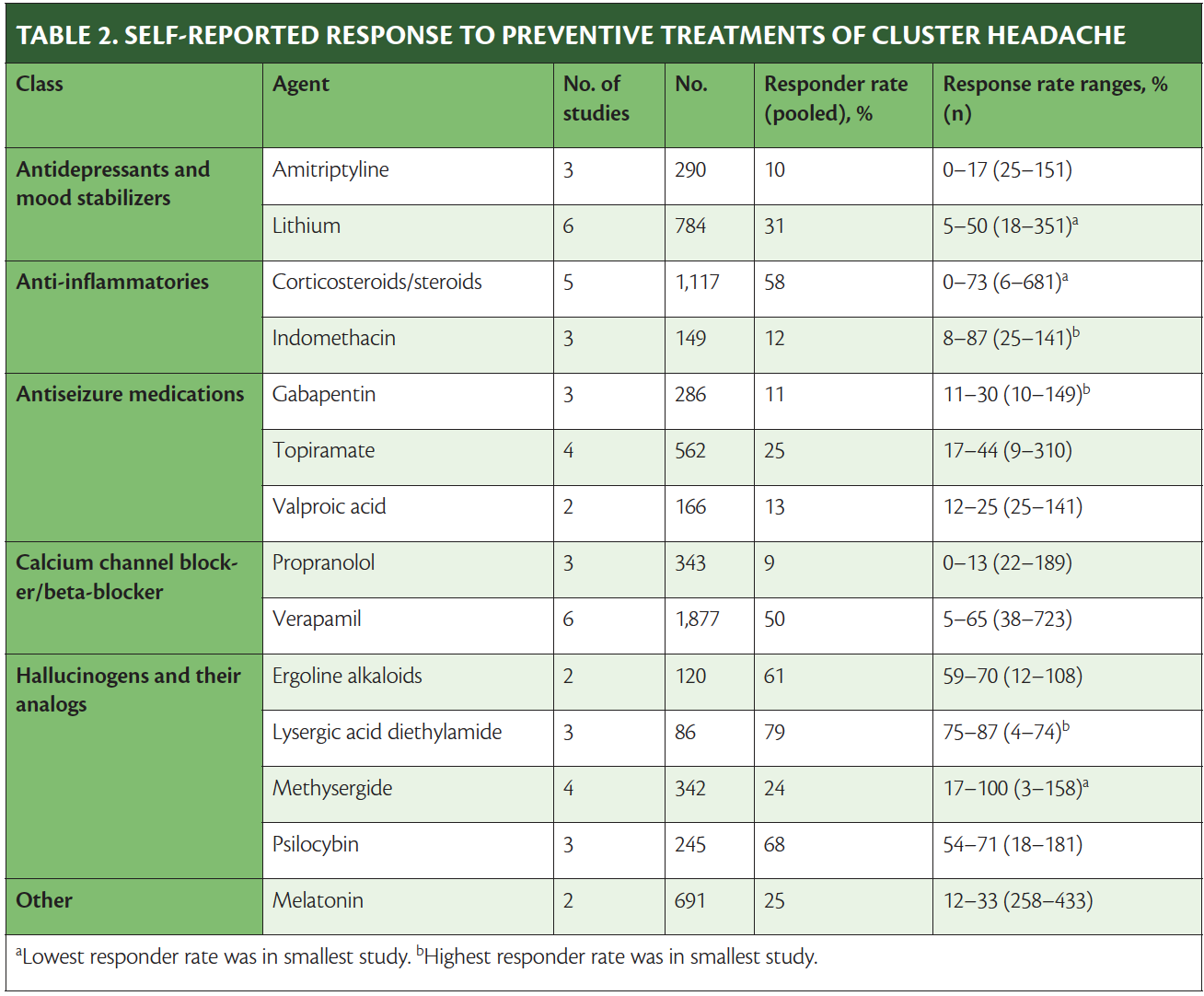

A recent systematic meta-analysis of published survey studies of 2 or more treatments for cluster headache, including psilocybin and LSD, included responses from 5419 people and showed that the main benefit of psilocybin and LSD was in prevention. Although the studies were small and retrospective, responder rates for prevention of cluster headache, as shown in Table 2, were highest with classic hallucinogens.6

Drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) that are commonly used for prevention of cluster headache (as indicated on the label or otherwise) also have limited evidence. Galcanezumab, a calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) antagonist recently approved for treatment of cluster headache, had only 1 clinical trial, which was terminated prematurely and the drug approved based on limited evidence of efficacy vs placebo for cluster headache.7,8 Use of verapamil is based on 1 placebo-controlled trial with 30 participants, 8 of whom had prior experience with verapamil,9 which usually is a reason to exclude someone from a trial. In 2 equally small comparative clinical trials, verapamil efficacy was established as being similar to that of nimodipine or lithium.10,11

Possible Mechanisms of Action

As mentioned, hallucinogens are serotonin agonists, as are some other approved pharmacologic treatments for headache (eg, triptans). Unlike triptans, however, hallucinogens cross the blood–brain barrier rapidly, which explains in part why they cause hallucinations. Because cluster headache has a circadian pattern, unlike other headache types, the hypothalamus is thought to be part of the causative pathway,12,13 which could explain why having a treatment that crosses the blood–brain barrier is important.

Hallucinogen Administration

The convention for use of hallucinogens for treatment of cluster headache has been that an individual stops other medications first to avoid any risk of drug–drug interactions, considering that no data from controlled studies of hallucinogens are available to provide guidance in that regard. After discontinuing other medications, an individual can start with a trial of hallucinogens. Experiencing hallucinations is not necessary for the hallucinogens to affect cluster headache, and many people attempt microdosing—taking the drug at lower amounts than will cause hallucinations. As mentioned, hallucinogens are not taken daily or regularly, but are used on days 1, 5, and 10 of treatment, followed by weeks or months of no use until another cluster attack occurs.

Morning glory seeds that contain ergotamine alkaloids14,15 may be the first hallucinogen a person tries because these are not illegal to purchase in the United States. The seeds are soaked in water to release the alkaloids and the water is then consumed. The seeds themselves can be toxic and are discarded. The alkaloids consumed have hallucinogenic potential but also may produce side effects of nausea or vomiting.

Psilocybin-containing mushrooms, which some people may use as a first attempt at this treatment, have become easier to obtain because purchase of the mushroom spores is legal in most US states. Directions for culture of these mushrooms have become more widely disseminated over the past 2 decades, although culture is legally prohibited. The hallucinogenic period for psilocybin is typically 6 hours.

Purchasing LSD is illegal in all states, making it more difficult to obtain, but some people find it more effective than psilocybin. The hallucinogenic period for LSD is approximately 12 hours.

Some individuals use N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT), also illegal in all states, which is the hallucinogenic agent in ayahuasca, although it can be more difficult to obtain than LSD. DMT has the shortest but most intense hallucinogenic period (~14 minutes) and also the fastest onset of action (on the order of seconds) when brewed and consumed as a tea. There is anecdotal evidence that DMT may be useful as an abortive treatment for cluster headaches.

Legal Considerations for the Physician

Physicians cannot legally prescribe, give, or help anyone obtain Schedule I drugs, but they may counsel patients about these agents. As well outlined in an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine,16 discussing any treatment option—legal or not, regulated or not, FDA-approved or not—falls into the realm of free speech. Thus, discussing these options with patients is protected and carries no risk. In contrast, not discussing treatment options does carry risk for patients, particularly when they live with a condition that is painful enough to be termed, by some, as suicide headache.

Many physicians are reticent to counsel patients about illicit drugs, which may explain why the majority of people using hallucinogens do not discuss it with their doctors. The prudent physician, however, should be aware that information about this option is widely available and many people with cluster headache will be aware of it. Physicians wishing to serve patients well should be open to a nonjudgmental conversation if a patient raises the subject of treatment with hallucinogens. I recommend the book Cluster Headaches: A Guide to Surviving One of the Most Painful Conditions Known to Man by Ashley S. Hattle17 to my patients with cluster headache; this book contains a wealth of useful information including and beyond use of hallucinogens.

It is also important to counsel patients on possible drug interactions if they are using these agents and also using prescription medications. This is a challenging topic and the message of the cluster headache community to try to discontinue all other medications first is helpful in this regard. Not all individuals can discontinue all other medications, however. For these individuals, there is little to no evidence of drug–drug interactions or other serious safety risks. I advise patients not to use triptans or other serotonergic agents and try to avoid verapamil, which is also used to treat cluster headache. Triptan use among people with cluster headache is not infrequent as many also have migraine.

Hallucinogens and Other Neuropsychiatric Conditions

Hallucinogens are being investigated for use in treatment of psychiatric conditions, especially mood disorders (including in the context of neurologic diseases [eg, multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer disease, Parkinson disease]), posttraumatic stress disorder, and substance use disorder. Psilocybin is also being investigated for treatment of migraine (Psilocybin for the Treatment of Migraine Headache [URL: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov; Unique identifier: NCT03341689] and Repeat Dosing of Psilocybin in Migraine Headache [URL: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov; Unique identifier: NCT04218539]) and posttraumatic headache (Effects of Psilocybin in Concussion Headache [URL: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov; Unique identifier: NCT03806985]).

Summary

Millions of individual exposures to hallucinogens have occurred through the decades and hallucinogenic agents have a high degree of safety, despite their negative public perception and stigma. Because of that stigma, deaths that have occurred while an individual was using a hallucinogen have been sensationalized in comparison with the far greater incidence of deaths attributable to alcohol use, which are common. As with many alternative medications, physicians need to be aware that patients are using these drugs to treat their disease and must remain open to conversations when a patient raises the subject. Because of the DEA scheduling of these drugs, despite the fact that they are not addictive or inherently harmful, practitioners must remain aware that they are judged differently from other pharmacologic agents.

1. Hollister LE. Chemical Psychoses. Charles C. Thomas; 1968.

2. Baumeister D, Barnes G, Giaroli G, Tracy D. Classical hallucinogens as antidepressants? A review of pharmacodynamics and putative clinical roles. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2014;4(4):156-169. doi:10.1177/2045125314527985

3. Glennon RA. Arylalkylamine drugs of abuse: an overview of drug discrimination studies. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1999;64(2):251-256. doi:10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00045-3

4. US Drug Enforcement Administration. Drug Scheduling. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://www.dea.gov/drug-information/drug-scheduling

5. Sewell RA, Halpern JH, Pope HG Jr. Response of cluster headache to psilocybin and LSD. Neurology. 2006;66(12):1920-1922. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000219761.05466.43

6. Rusanen SS, De S, Schindler EAD, Artto VA, Storvik M. Self-reported efficacy of treatments in cluster headache: a systematic review of survey studies. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2022;26(8):623-637. doi:10.1007/s11916-022-01063-5

7. Goadsby PJ, Dodick DW, Leone M, et al. Trial of galcanezumab in prevention of episodic cluster headache. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(2):132-141. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1813440

8. Dodick DW, Goadsby PJ, Lucas C, et al. Phase 3 randomized, placebo-controlled study of galcanezumab in patients with chronic cluster headache: results from 3-month double-blind treatment. Cephalalgia. 2020;40(9):935-948. doi:10.1177/0333102420905321

9. Leone M, D’Amico D, Frediani F, et al. Verapamil in the prophylaxis of episodic cluster headache: a double-blind study versus placebo. Neurology. 2000;54(6):1382-1385. doi:10.1212/wnl.54.6.1382

10. Bussone G, Leone M, Peccarisi C, et al. Double blind comparison of lithium and verapamil in cluster headache prophylaxis. Headache. 1990;30(7):411-417. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.1990.hed3007411.x

11. Meyer JS, Hardenberg J. Clinical effectiveness of calcium entry blockers in prophylactic treatment of migraine and cluster headaches. Headache. 1983;23(6):266-277. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.1983.hed2306266.x

12. Naber WC, Fronczek R, Haan J, et al. The biological clock in cluster headache: a review and hypothesis. Cephalalgia. 2019;39(14):1855-1866. doi:10.1177/0333102419851815

13. Lee DA, Lee J, Lee HJ, Park KM. Alterations of limbic structure volumes and limbic covariance network in patients with cluster headache. J Clin Neurosci. 2022;103:72-77. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2022.07.003

14. Zia-Ul-Haq M, Riaz M, De Feo V. Ipomea hederacea Jacq.: a medicinal herb with promising health benefits. Molecules. 2012;17(11):13132-13145. doi:10.3390/molecules171113132

15. Chaudhry MA, Alamgeer, Mushtaq MN, Bukhari IA, Assiri AM. Ipomoea hederacea Jacq.: a plant with promising antihypertensive and cardio-protective effects. J Ethnopharmacol. 2021;268:113584. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2020.113584

16. Annas GJ. Medical marijuana, physicians, and state law. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(11):983-985. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1408965

17. Hattle AS. Cluster Headaches: A Guide to Surviving One of the Most Painful Conditions Known to Man. BookBaby; 2017.

BEM reports no disclosures.