Rabies is a fatal zoonotic infection that is responsible for almost 60,000 deaths annually throughout the world. As in many developing Asian countries, canine rabies remains endemic in the state of Sarawak in Malaysia. A rabies outbreak in Sarawak started in July 2017, when the index case was reported. To date, a total of 72 areas in Sarawak have been declared as rabies-infected areas. There were a total of 31 cases of rabies death from July 2017 to March 2021.1

Immediate local wound management with adequate wound washing and timely postexposure prophylaxis (PEP), which includes a series of rabies vaccines with or without rabies immunoglobulin (RIG) during the first dose of rabies vaccine, are the most important steps in preventing rabies after an exposure.

Rabies death following PEP and RIG is rare and usually associated with certain deviations of practice from protocol.2 A study in Sarawak by Chua et al3 reported that 82 out of 83 people bitten by laboratory-confirmed rabies virus–infected animals were alive during 1-year follow up after completing PEP and RIG as per local protocol. Only one person who sustained a high-risk bite over the neck and face developed and died of human rabies during this 1-year follow up.3 We report a case of rabies death despite completing a full course of PEP including RIG administration.

Case Presentation

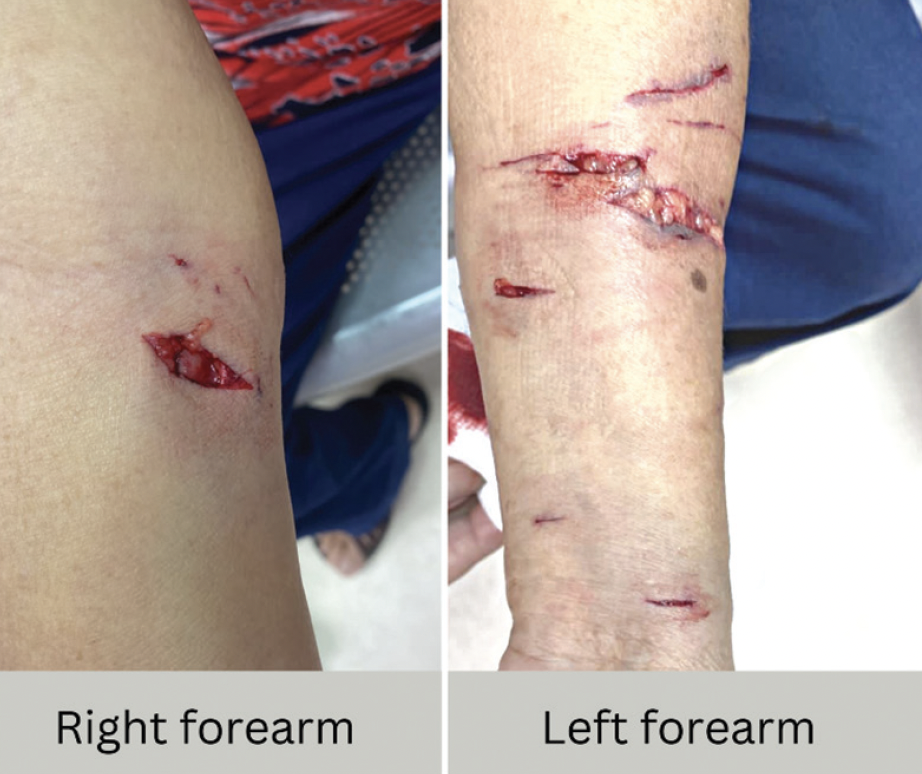

A woman in her 70s was bitten by a stray dog and sustained multiple category 3 wounds on both forearms (Figure 1). She presented to the emergency department 1 hour after the incident. Wound irrigation was performed, and the wounds were infiltrated with equine RIG. Verorab (Sanofi Pasteur, Lyon, France) was given according to the Institut Pasteur du Cambodge (IPC) regimen. Local wound debridement was performed 52 hours after the incident.

The patient’s past medical history included hypertension and lacunar infarction with good neurologic recovery. She also had had right breast carcinoma, for which a radical mastectomy was done in 2006 followed by radiotherapy and chemotherapy. She was discharged as well by the oncology team. The patient was not immunocompromised.

About 1 month later, the patient presented to us again with numbness and weakness over her bilateral upper limbs for 3 days associated with fever. She had no hydrophobia or aerophobia. She did not report any hypersalivation or hyperirritability. On examination, she was alert, with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 15/15. Both upper limbs were weak and could barely resist gravity, with a Medical Research Council grade of 3/5. Upper limb reflexes were not elicitable. Pinprick sensation was generally reduced. Both lower limb examinations were normal. There was no demonstrable cranial nerve palsy, and no signs of meningism. Complete blood counts, renal profile, and electrolytes were unremarkable. A plain CT of the brain showed only old lacunar infarcts with no cerebral edema.

The patient was admitted for presumed rabies given the recent high-risk dog bite. A few hours after admission, she had reduced consciousness, with Glasgow Coma Scale score E2 V2 M5, while waiting for an MRI brain scan. Endotracheal intubation was performed to secure the airway.

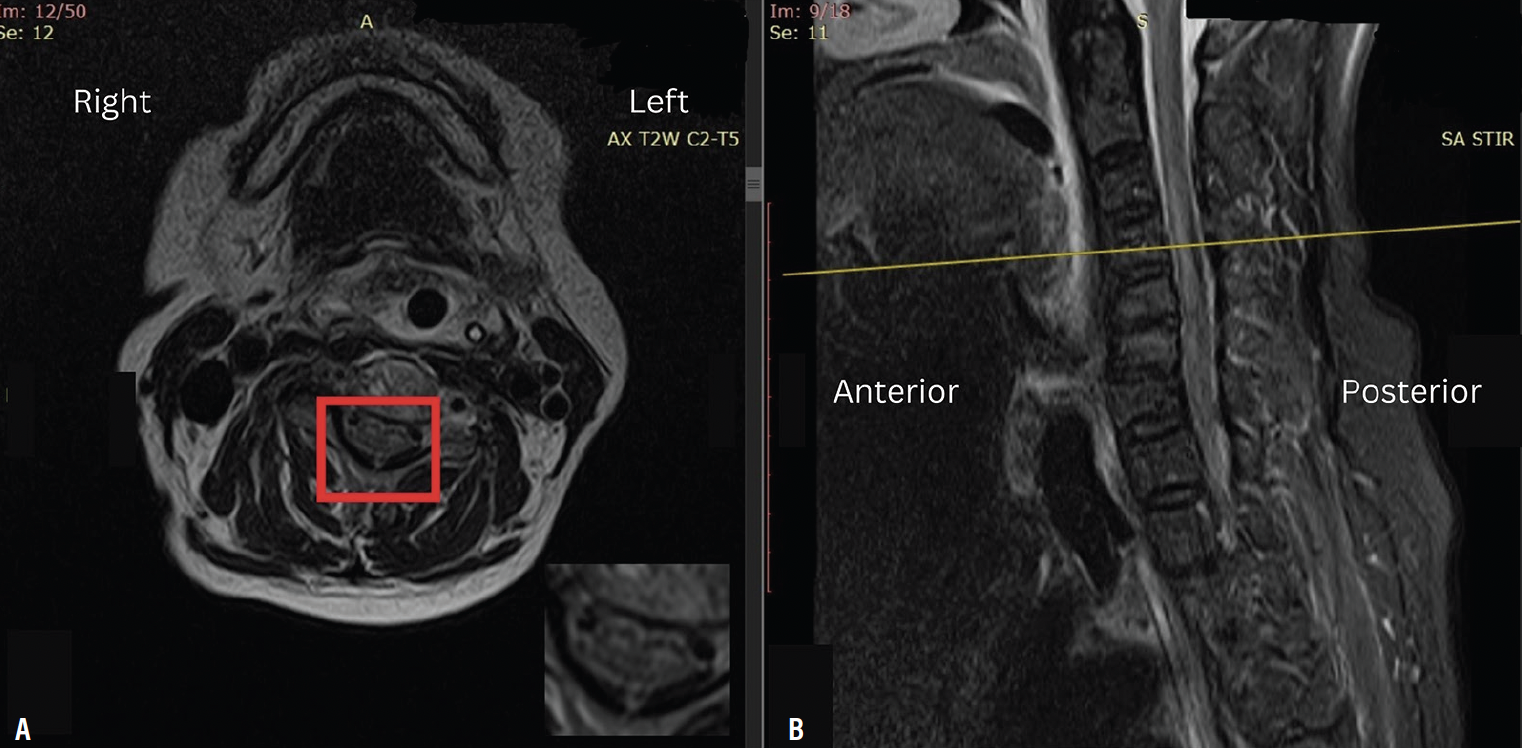

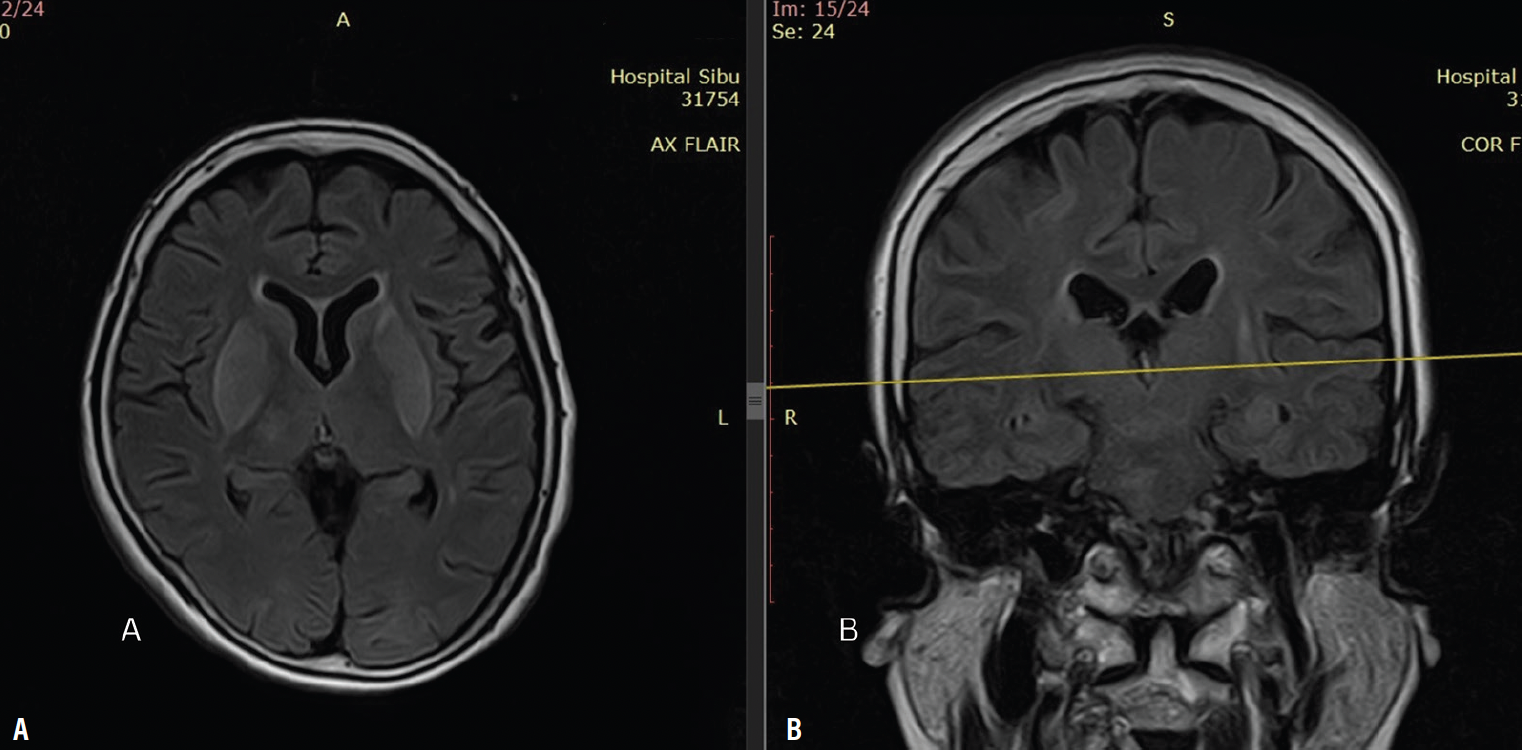

MRI showed abnormal hyperintensity signals at both lentiform nuclei, thalami, caudate nuclei, and hippocampus, as well as in pons, midbrain, and medulla oblongata on T2-weighted images (Figure 2). Restricted diffusion was noted on diffusion-weighted imaging and patchy enhancement was evident in the postcontrast study. There was also a long segment of intramedullary hyperintense signal on T2-weighted images from spinal level C3 to T3, predominantly affecting the anterior horn of the spinal cord (Figure 3).

A lumbar puncture was performed, revealing an opening pressure of 14 cm H2O, cerebrospinal fluid cell count 0, cerebrospinal fluid protein 1.03 g/L, cerebrospinal fluid to blood glucose ratio 0.57, and cerebrospinal fluid culture negative. Rabies virus was detected using real-time polymerase chain reaction in the cerebrospinal fluid sample but not in saliva or urine samples.

Diagnosis of rabies encephalomyelitis was made. This patient received supportive care and died of the illness 2 days later.

Discussion

Human rabies occurs in 2 distinct forms: 1) paralytic and 2) encephalitic. In general, the incubation period varies from 20 to 90 days, but it could be up to several years. It is almost always fatal once clinical signs of rabies have developed. Our patient presented with a paralytic form of rabies within this period. On admission, she was alert. Neurologic progression was rapid; the patient became comatose and died within a short period.4,5

Laothamatas et al6 described abnormal T2 hyperintensity signals in the brainstem, hippocampus, hypothalamus, deep and cortical gray matter, and gray matter of the spinal cord in their case series of individuals with rabies. MRI brain findings in our patients were similar to those reported in the available literature.5-8 There are characteristic abnormal signals in T2-weighted images involving deep grey nuclei and the brainstem.

The purified Vero cell rabies vaccine, Verorab, is a World Health Organization–prequalified rabies vaccine that is used in both preexposure prophylaxis and PEP. Since 2018, the World Health Organization guidelines have recommended the IPC regimen, which consists of 1 week of 2-site injections on days 0, 3, and 7, with 0.1 mL intradermal Verorab given at 2 sites during each visit.2

A cohort series reported by Chua et al3 showed promising results. A total of 82 out of 83 people who were bitten by laboratory-confirmed rabies-infected animals and completed the IPC regimen with or without RIG were alive at 1 year of follow up. These people had proper wound washing for 15 minutes as per local protocol with complete PEP including RIG over wounds before operative wound management.

In a case series of fatal rabies reported by Wilde et al,4 all 5 children reported had sustained multiple severe bites and completed RIG with a series of vaccines and died of rabies.4 It was elaborated in the report that not all wounds had been infiltrated with RIG and surgical closure of the wound was performed before RIG infiltration over the wounds.

Our patient completed a full course of vaccination according to the IPC regimen after adequate wound washing as per local protocol followed by administration of equine RIG as passive immunization before wound debridement; however, she died of rabies. A retrospective review of staff and protocol at the emergency department where wound washing of this patient was performed during the first hospital visit revealed no violation of protocol. Wounds were infiltrated with equine RIG appropriately according to the local protocol.

Wound irrigation is the single most important step in preventing rabies. However, thorough wound washing can be challenging, especially in people with multiple bite or scratch wounds. Proper wound irrigation in a controlled environment may improve the quality of local wound management. Our patient had wound debridement performed 52 hours after the bites because of limited operating theatre availability which may pose a potential pitfall.

Conclusion

Rabies is a life-threatening zoonotic infection that is nearly always fatal after clinical signs have developed. The diagnosis is secured by a compatible history of rabid animal bite with progressive rhomboencephalitis, ultimately leading to death. The predilection of gray matter and brainstem to show abnormal hyperintense signal on T2-weighted images in an MRI of the brain can raise the suspicion of rabies even before laboratory confirmation can be obtained as not all centers run these tests. Hence, every person with high-risk exposure should receive proper wound management that includes adequate wound washing with running water and soap followed by RIG and vaccination. PEP is important after bites from a rabid animal have occurred. PEP needs to be administered with strict adherence to protocol; failure to follow protocol may result in clinical manifestation of human rabies. Wound debridement should be delayed for at least 6 hours after RIG infiltration for people who sustain multiple deep wounds.

1. Sarawak Disaster Management Committee. Sarawak Disaster Information: Rabies Info. Published March 19, 2021. https://infodisaster.sarawak.gov.my

2. World Health Organization. WHO Expert Consultation on Rabies, Third Report: WHO Technical Report Series, No. 1012. World Health Organization; 2018.

3. Chua HH, Chang AKW, Thangavelu S, Tay SLH, Perera D, Ooi MH. A Sarawak experience on the use of IPC ID PEP regimen in patients bitten by laboratory confirmed rabies animals. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;101(suppl. 1):466. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.09.1221

4. Wilde H, Sirikawin S, Sabcharoen A, et al. Failure of postexposure treatment of rabies in children. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22(2):228-232. doi:10.1093/clinids/22.2.228

5. Dattatraya Bhat M, Priyadarshini P, Prasad C, Kulanthaivelu K. Neuroimaging findings in rabies encephalitis. J Neuroimaging. 2021;31:609-614. doi:10.1111/jon.12833

6. Laothamatas J, Hemachudha T, Mitrabhakdi E, Wannakrairot P, Tulayadaechanont S. MR imaging in human rabies. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24:1102-1109.

7. Ng Han Sim B, Ng Wei Liang B, Sheau Ning W, Viswanathan S. A retrospective analysis of emerging rabies: a neglected tropical disease in Sarawak, Malaysia. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2021;51:133-139. doi:10.4997/JRCPE.2021.207

8. Mani J, Reddy BC, Borgohain R, Sitajayalakshmi S, Sundaram C, Mohandas S. Magnetic resonance imaging in rabies. Postgrad Med J. 2003;79:352-354.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the infectious disease physicians of Sarawak General Hospital and all the people involved in the care of this patient.