Essential tremor (ET) is among the most common movement disorders and neurologic conditions, with an overall prevalence of 1.3%. It increases in prevalence with age, reaching 6% in people age 60 to 65 years and continuing to rise thereafter.1 The condition is characterized by a postural or kinetic tremor, or both, with a frequency of 4 to 12 Hz, which typically presents in the upper extremities.2 With age and longer duration of the condition, the tremor has been noted to worsen, with an increase in amplitude and decrease in frequency.3 As the disease progresses, tremor can spread to the lower extremities, head, neck, and voice. Additional motor symptoms include gait ataxia and mild saccades. Nonmotor symptoms include psychiatric and emotional problems, such as depression and anxiety—especially social anxiety—as well as cognitive, auditory, and olfactory deficits.4,5

Pathophysiology of ET

The pathophysiology of ET has yet to be determined, and its elucidation is hampered by the heterogeneous nature of its presentation and causation. Several hypotheses have been presented to explain ET. The neurodegeneration hypothesis posits deterioration of the cerebellum and locus coeruleus, but research in this area is lacking. A decrease in GABAergic tone within the cerebellum and locus coeruleus is another potential explanation for the development of ET.6 Increasing focus on the role of the cerebellum in ET has revealed alterations in Purkinje fibers in postmortem studies, with some studies demonstrating a decreased number of Purkinje fibers. Considering cerebellar innervation by noradrenergic neurons originating in the locus coeruleus, which in turn synapse with the Purkinje fibers, greater attention is being given to the role of cerebellar tracts in ET disease pathology.4

Etiologic considerations of ET have revealed both genetic and environmental influences in its development. Studies have demonstrated autosomal dominant inheritance patterns, with first-degree relatives having a 5 times increased chance of developing the condition. Concurrent existence of isolated and sporadic cases with no genetic or familial connection are evidence of potential environmental factors, such as toxins, having a role in the development of ET. Lead and beta-carboline alkaloids are being investigated for their potential association with ET. Studies focused on isolating ET-specific genes are underway, but the complexity of disease development suggests an equally complex and polygenetic etiology.4

Treatment of ET

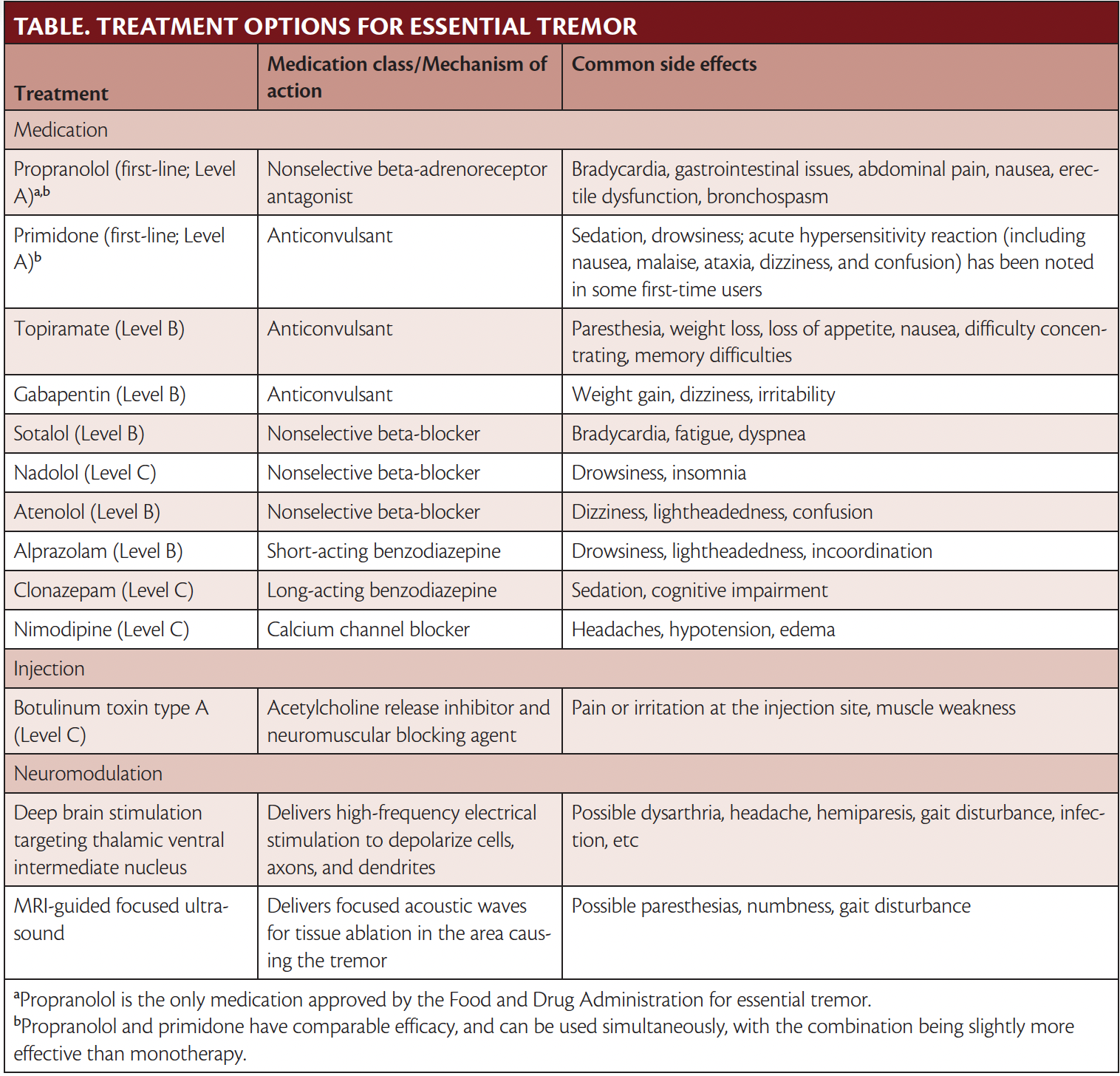

American Academy of Neurology guidelines categorize ET treatments according to efficacy and safety into the following categories:4a

- Level A, effective

- Level B, probably effective

- Level C, possibly effective

- Level U, insufficient evidence

First Line of Treatment: Propranolol or Primidone

Propranolol is the first line of treatment and the only therapy approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for ET. Traditionally used in treatment of hypertension, propranolol is a nonselective antagonist of the peripheral beta receptors found in muscles. Propranolol has been studied in many randomized controlled trials (RCT) (13 Level 1 trials including 255 participants overall) with demonstrated efficacy in treatment of ET.4b A total of 50% to 60% of individuals experience an improvement in tremor when treated with propranolol, with the greatest improvement seen in upper limb tremor. Propranolol has been found to be most effective when used in treatment of low-frequency, high-amplitude tremors. Whereas dosage tends to be specific to the individual, 1 double-blind RCT found that a dosage ranging from 240 to 320 mg was the most effective in treatment of tremor.4c Treatment is initiated at 10 mg and titrated upward until peak efficacy is reached. Long-acting propranolol also is available and has comparable efficacy.

People with contraindications to propranolol, such as conduction block, depression, or diabetes, or who do not experience amelioration of tremor with propranolol, often are prescribed primidone (Mysoline; Bausch Health, Bridgewater, NJ). Primidone (Level A) is an anticonvulsant and another first-line treatment for ET that shows comparable efficacy with propranolol. Eight Level 1 trials including 274 total participants revealed that primidone was efficacious in treatment of ET, specifically in regard to tremor amplitude and activities of daily living.4b Both propranolol and primidone have been proven to be useful in treatment of ET; however, primidone has significant side effects, and an acute toxic reaction has been noted in first-time users. Symptoms of this toxic reaction often include nausea, malaise, ataxia, dizziness, and confusion. As such, dosing is started very low and titrated up based on tolerability and safety.

In the case that monotherapy with primidone or propranolol is ineffective, both can be used simultaneously, with a slight improvement shown with the combination in comparison to monotherapy. This combination has been shown to be more effective for treatment of head tremor than propranolol or primidone alone.

Topiramate

Topiramate (Level B) is an anticonvulsant found to be effective for treatment of ET. Analysis of combined data from 3 Level 1 placebo-controlled RCT7-9 revealed a significant reduction in tremor severity and improvement in activities of daily living and motor performance with topiramate. The mean effective dose across the 3 studies was 215 to 333 mg.10 However, another placebo-controlled RCT did not find a significant improvement in limb tremor.11 All 4 trials had a high dropout rate because of adverse events (eg, paresthesia, weight loss, loss of appetite, nausea, memory difficulties). Further studies should be conducted to confirm the efficacy of topiramate for treatment of ET. In the clinic, treatment is initiated at 25 to 50 mg. Attention should be paid to side effects and these side effects weighed against potential benefits for the individual’s ET in determining correct dosage.

Gabapentin

Gabapentin (Level B) is an anticonvulsant that has demonstrated mixed results for the treatment of ET, both as monotherapy and add-on therapy. One placebo-controlled trial of 1800 mg gabapentin did not report significant improvements in tremor assessments when comparing the treatment arm with placebo.12 However, a double-blind crossover trial comparing effects of gabapentin and propranolol found that the drugs had comparable efficacy in treatment of essential tremor.13 Anecdotally, gabapentin can be useful for some people with ET who do not benefit from Level A treatments, but additional RCTs must be conducted to confirm whether there is true benefit when using gabapentin for treatment of ET. Side effects of gabapentin include weight gain, dizziness, and irritability. Dosing is started at 300 mg 3 times a day or lower, depending on patient age and comorbid conditions.

Other Beta-Blockers

Whereas propranolol is the first line of ET treatment, other beta-blockers have been studied and demonstrated possible efficacy as ET treatments. Sotalol (Level B) is a nonselective beta-blocker that was compared with metoprolol and atenolol in a crossover trial. Maximum efficacy of sotalol was noted at doses of 75 to 200 mg.14 Nadolol (Level C), another nonselective beta-blocker, was studied in a small trial, and found to be effective at 120 and 240 mg, but efficacy was limited to those individuals who had previously had success when treated with propranolol. Atenolol (Level B) is a selective adrenergic antagonist that can be used as an alternative for people who experience side effects, especially bronchospasm, from nonselective beta-blockers. One placebo-controlled trial comparing atenolol with propranolol found no significant difference between the 2 treatments, and found that both improved tremor.15 Propranolol remains the standard of ET treatment, but the potential efficacy of other beta-blockers opens up possibilities for individuals who experience intolerable side effects or nonresponse to propranolol.

Benzodiazepines: Alprazolam and Clonazepam

Alprazolam (Level B) is a short-acting benzodiazepine that showed efficacy for treatment of ET in 2 Level 1 studies. One double-blind crossover trial studied the effect of alprazolam at doses of 0.75 to 3 mg and found improvement of tremor.15a Studies on the use of clonazepam (Level C) for treatment of ET have yielded mixed results. One trial comparing propranolol with clonazepam for ET treatment found clonazepam to be useful for kinetic tremor.16 Another study using 4 mg of clonazepam per day did not show any improvement in tremor.17 Alprazolam and clonazepam may be helpful for individuals experiening a worsening in their tremors. However, clinicians may be cautious in prescribing these medications because of high potential for abuse. Side effects include withdrawal, sedation, and cognitive impairment.

Nimodipine

Nimodipine (Level C), a calcium channel blocker used to treat vasospasms secondary to subarachnoid bleeding, has been studied for treatment of ET. One double-blind placebo-controlled trial of 30 mg of nimodipine found an improvement in tremor in 50% of individuals, and the medication was generally well-tolerated. Side effects of nimodipine include headaches, hypotension, and edema.18 To better evaluate the effect of nimodipine on ET, further RCTs should be conducted to establish efficacy.

Botulinum Toxin

Botulinum toxin type A (Level C) has been studied for treatment of medically refractory ET. Two placebo-controlled RCTs demonstrated improvement in the clinical rating of limb tremor; however, functional improvement was not noted in either trial. One parallel-group RCT saw 60% to 70% improvement of postural hand tremor, but without functional improvement. All but 1 participant experienced weakness of the wrist and fingers.19 Another double-blind placebo-controlled trial saw improvement in both postural and kinetic tremor with botulinum toxin, again without functional improvement.20 Botulinum toxin can be used for treatment of limb tremor (when injected into the forearm) and head tremor (when injected into the neck). The use of botulinim toxin is limited for the upper limbs because of the side effect of weakness.

Neuromodulation

Between 30% and 50% of individuals treated with pharmacologic agents will experience no amelioration of their tremor, and 50% of those who experience initial benefits will reach an eventual plateau in their improvement or have dose-dependent side effects. Because of the limitations of pharmacologic therapies, deep brain stimulation and MRI-guided focused ultrasound have become increasingly attractive options for people with ET.5,21 Studies investigating the effects of deep brain stimulation on ET have had positive results, with many studies demonstrating statistically significant improvements in tremor. Deep brain stimulation is favored over thalamotomy because it is associated with fewer side effects and complications. The ventral intermediate nucleus of the thalamus is 1 major point of focus in deep brain stimulation research, and targeting the ventral intermediate nucleus has proven to be effective in treatment of ET. Focused ultrasound is a noninvasive alternative that uses focused acoustic waves for tissue ablation in the area causing the tremor. One parallel-group RCT of focused ultrasound found improvement in hand tremor that was maintained at 12 months postprocedure.22 Adverse events of focused ultrasound include gait disruption that may be transient; further research must be conducted to understand how to mitigate this risk, if possible.

Conclusion

Although no cure for ET exists, treatment advancements have been increasing. No other drugs or treatments have achieved the same status as propranolol, however, which was approved by the FDA in 1967. The need for effective treatments with minimal side effects is ongoing and increasing in need as the population ages, which will lead to a dramatic increase in the number of people with ET.

1. Louis ED, McCreary M. How common is essential tremor? Update on the worldwide prevalence of essential tremor. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y). 2021;11:28. doi:10.5334/tohm.632

2. Lenka A, Jankovic J. Tremor syndromes: an updated review. Published online July 26, 2021. Front Neurol. doi:10.3389/fneur.2021.684835

3. Agarwal S, Biagioni MC. Essential tremor. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing: 2019. Accessed August 25, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499986

4. Clark LN, Louis ED. Essential tremor. Handb Clin Neurol. 2018;147:229-239. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-63233-3.00015-4

4a. Zesiewicz TA, Elble RJ, Louis ED, et al. Evidence-based guideline update: treatment of essential tremor: report of the Quality Standards subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2011 Nov 8;77(19):1752-5. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318236f0fd. Epub 2011 Oct 19. PMID: 22013182; PMCID: PMC3208950.

4b. Ferreira JJ, Mestre TA, Lyons KE, et al: MDS evidence-based review of treatments for essential tremor. Mov Disord. 2019 Jul;34(7):950-958. doi: 10.1002/mds.27700. Epub 2019 May 2.

4c. Koller WC. Propranolol therapy for essential tremor of the head. Neurology. 1984 Aug;34(8):1077-9. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.8.1077. PMID: 6379505.

5. Wong JK, Hess CW, Almeida L, et al. Deep brain stimulation in essential tremor: targets, technology, and a comprehensive review of clinical outcomes. Expert Rev Neurother. 2020;20(4):319-331. doi:10.1080/14737175.2020.1737017

6. Helmich RC, Toni I, Deuschl G, Bloem BR. The pathophysiology of essential tremor and Parkinson’s tremor. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2013;13(9):378. doi:10.1007/s11910-013-0378-8

7. Connor GS, Edwards K, Tarsy D. Topiramate in essential tremor: findings from double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trials. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2008;31(2):97-103. doi:10.1097/WNF.0b013e3180d09969

8. Connor GS. A double-blind placebo-controlled trial of topiramate treatment for essential tremor. Neurology. 2002;59(1):132-134. doi:10.1212/wnl.59.1.132

9. Ondo WG, Jankovic J, Connor GS, et al; Topiramate Essential Tremor Study Investigators. Topiramate in essential tremor: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 2006;66(5):672-677. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000200779.03748.0f

10. Ferreira JJ, Mestre TA, Lyons KE, et al; MDS Task Force on Tremor and the MDS Evidence Based Medicine Committee. MDS evidence-based review of treatments for essential tremor. Mov Disord. 2019;34(7):950-958. doi:10.1002/mds.27700

11. Grünewald RA. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial of topiramate in essential tremor. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2006;29(2):94-96. doi:10.1097/00002826-200603000-00007

12. Pahwa R, Lyons K, Hubble JP, et al. Double-blind controlled trial of gabapentin in essential tremor. Mov Disord. 2000;15(4):678-682. doi:10.1002/1531-8257(200007)15:4<678::aid-mds1012>3.0.co;2-0

13. Ondo W, Hunter C, Dat Vuong K, Schwartz K, Jankovic J. Gabapentin for essential tremor: a multiple-dose, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Mov Disord. 2000;15(4):678-682. doi:10.1002/1531-8257(200007)15:4<678::aid-mds1012>3.0.co;2-0

14. Leigh PN, Jefferson D, Twomey A, Marsden CD. Beta-adrenoreceptor mechanisms in essential tremor: a double-blind placebo controlled trial of metoprolol, sotalol and atenolol. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1983;46(8):710-715. doi:10.1136/jnnp.46.8.710

15. Larsen TA, Teräväinen H, Calne DB. Atenolol vs. propranolol in essential tremor: a controlled, quantitative study. Acta Neurol Scand. 1982;66(5):547-554. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.1982.tb03141.x

15a. Huber SJ, Paulson GW. Efficacy of alprazolam for essential tremor. Neurology. 1988 Feb;38(2):241-3. doi: 10.1212/wnl.38.2.241. PMID: 3340287.

16. Koller W. Kinetic predominant essential tremor: successful treatment with clonazepam. Neurology. 1987;37(3):471-474. doi:10.1212/wnl.37.3.471

17. Thompson C, Lang A, Parkes JD, Marsden CD. A double-blind trial of clonazepam in benign essential tremor. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1984;7(1):83-88. doi:10.1097/00002826-198403000-00004

18. Biary N, Bahou Y, Sofi MA, Thomas W, al Deeb SM. The effect of nimodipine on essential tremor. Neurology. 1995;45(8):1523-1525. doi:10.1212/wnl.45.8.1523

19. Jankovic J, Schwartz K, Clemence W, Aswad A, Mordaunt J. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to evaluate botulinum toxin type A in essential hand tremor. Mov Disord. 1996;11(3):250-256. doi:10.1002/mds.870110306

20. Brin MF, Lyons KE, Doucette J, et al. A randomized, double masked, controlled trial of botulinum toxin type A in essential hand tremor. Neurology. 2001;56(11):1523-1528. doi:10.1212/wnl.56.11.1523

21. Zesiewicz TA, Elble RJ, Louis ED, et al. Evidence-based guideline update: treatment of essential tremor: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2011;77(19):1752-1755. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e318236f0fd

22. Elias WJ, Lipsman N, Ondo WG, et al. A randomized trial of focused ultrasound thalamotomy for essential tremor. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(8):730-739. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1600159

Shaila Ghanekar reports no disclosures.

Dr. Zesiewicz has received personal compensation for serving on the advisory boards of Boston Scientific; Reata Pharmaceuticals, Inc; and Steminent Biotherapeutics; has received personal compensation as senior editor for Neurodegenerative Disease Management and as a consultant for Steminent Biotherapeutics; has received royalty payments as co-inventor of varenicline for treating imbalance (patent number 9,463,190) and nonataxic imbalance (patent number 9,782,404); has received research/grant support as principal investigator/investigator for studies from AbbVie Inc, Biogen, Biohaven Pharmaceutics, Boston Scientific, Bukwang Pharmaceuticals Co, Ltd, Cala Health, Inc, Cavion, Friedreich’s Ataxia Research Alliance, Houston Methodist Research Institute, National Institutes of Health (READISCA U01), Retrotope Inc, and Takeda Development Center Americas, Inc; and has received clinical trial funding by Jazz Pharmaceuticals and Sage Pharmaceuticals.