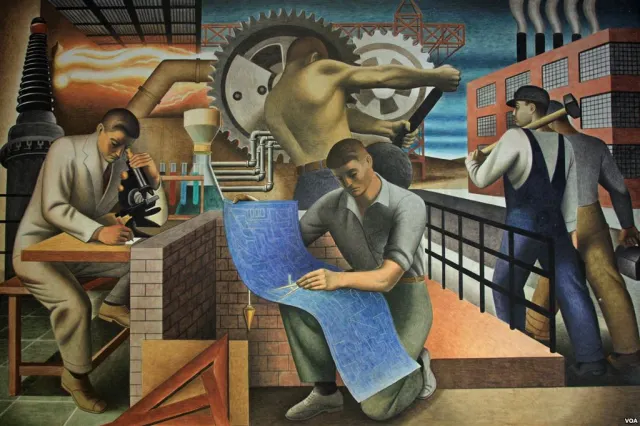

Seymour Fogel’s “The Wealth of the Nation,” located at the Department of Health and Human Services

Murals from the Depression era are being regularly rediscovered and, more often than not, restored. The works created for the Works Progress Administration – with their idealized representations of struggling Americans and their faith in the virtue of community and cooperation – speak to our current recessionary moment. Once thought unfashionable and outmoded, the murals painted by the WPA’s artists are now imbued with new relevance.

The WPA, at its height, employed 5,000 American artists, paying them between $25 and $35 per week to create works for public display. The agency counted Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning, and Jackson Pollock as employees.

New York City has devised a program to save the many WPA murals it houses. The U.S. Postal Service is conserving surviving WPA art in its post offices and the U.S. General Services Administration is cataloging any remaining art created with WPA funding. Even small communities like Gloucester, Massachusetts are working to preserve the WPA’s legacy.

An artist had this to say about Gloucester’s collection of WPA murals: “If this fabulous collection of murals can be used as a locus for a discussion on the arts and the roles of artists in society under the New Deal, if they could be a door into an educational and thoughtful examination of a time relevant to our present situation…Perhaps we as a community in Gloucester at least can look at the past and think differently and creatively about the present and future.”

Heather Beck, an artist and the CEO of The Chicago Conservation Center is glad that art from the WPA is being reevaluated. She says, “Some people weren’t sure of its quality,” she says. “Some of the work wasn’t accepted because it was considered too modern. … It wasn’t until later that people started realizing how great the images are.”

For a select few artists, this new vogue for all things WPA has precipitated a resurgence in popularity: one such artist is the New York Modernist Seymour Fogel.

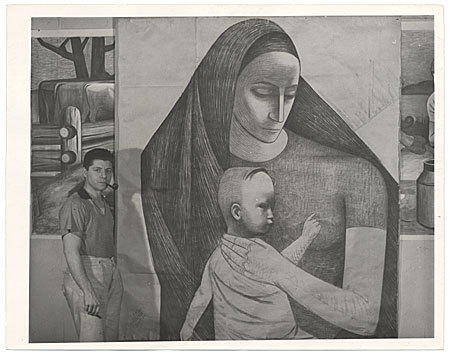

Seymour Fogel’s 1939 World’s Fair Mural, in New York City

Fogel at work on the 1939 World’s Fair mural

The Murals of Seymour Fogel

Seymour Fogel, though not initially trained as a muralist, became one of the country’s foremost mural painters.

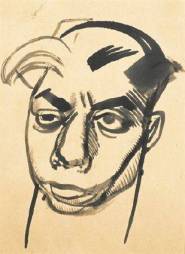

Seymour Fogel, “Portrait of Diego Rivera,” 1933, ink on paper

Credit for this development can go to Fogel’s first tutor: the storied Mexican muralist and political provocateur Diego Rivera. After graduating from New York’s National Academy of Design, a frustrated Fogel said, “I could copy most anything, draw the human figure and paint it, and nothing else. I didn’t know what a painting really was, how to create anything, and my impressionable mind was firmly molded in academic Papier-mâché.” Rivera, who conscripted Fogel to assist him with the completion of the titanic and controversial mural Man at the Crossroads soon taught him “what painting really was.”

The artist Boris Gorelick said the following about the association between Fogel and Rivera: “Rivera had a tremendous influence on many of the mural painters at that time. Seymour Fogel, for example, was a student of Mr. Rivera during that period. As a matter of fact, he worked as an assistant of his on the Radio City job and got his first mural training from him. I remember very well Rivera’s stay in New York. As a cultural force in New York, [Rivera] made rather a significant contribution to the general ferment that was going on there.”

Fogel assimilated much of Rivera’s method, as well as his revolutionary zeal. The drawings and lithographs he completed in the 1930s were concerned with the plight of dispossessed farmers and laborers, poor black sharecroppers in the South and battered refugees of the Dust Bowl. Fogel’s critical view of inequality was, if not wholly derived from Rivera, sharpened and honed under the Mexican artist’s tutelage.

Seymour Fogel, “Diego Rivera at Work on Rockefeller Center Mural,” 1933, mixed media on board

Between 1934 and 1941, Fogel was awarded a number of mural commissions by the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration. He painted murals at the Abraham Lincoln High School in Brooklyn, New York in 1936; the WPA Building at the 1939-1940 New York World’s Fair; the U.S. Post Office in Safford, Arizona; and two murals in the Social Security Building in Washington, D.C., also in 1941.

At the time, Fogel was counted among the leading Modernists in the country; he was acquainted with Phillip Guston, Ben Shahn, Franz Kline, Rockwell Kent and Willem de Kooning. He would, like many of these artists, later credit the WPA with rescuing him financially and starting his art career.

Fogel accepted a teaching position at The University of Texas at Austin in 1946 and, soon after his arrival in the Lone Star State, began to execute murals unique for their abstract qualities, approaching a kind of Cubism. Before leaving Texas in 1959, Fogel completed murals for the American National Bank in Austin, the Baptist Student Center at the University of Texas, the First National Bank in Waco, the First Christian Church in Houston, and Houston’s Petroleum Club.

By the end of his life, Fogel had created more than 20 major murals throughout the United States.

Some of these murals were endangered or swept away by development projects. Others, like the mural detailed below, were forgotten altogether. Fogel’s national standing declined with the loss of each of his murals.

A Masterpiece of Modern Art Imperiled

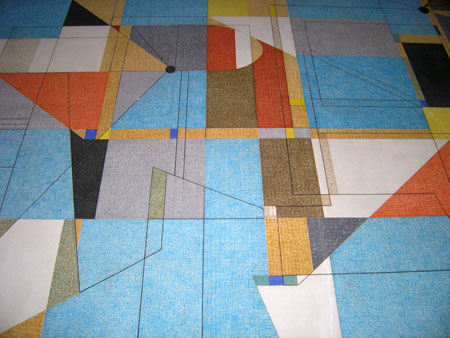

In 1954, Seymour Fogel was commissioned to paint a mural for the American National Bank in Austin, Texas. The mural was completed in 1955 and was distinct for its geometric patterns and use of vibrant, primary colors. Fogel painted the mural directly onto the Bank’s wall, arguing that doing so lent it an organic quality. He explained, after completing the gigantic 11×30 foot mural, “It wasn’t done at home and then pasted up there. It’s a part of the wall; it grew with the Bank’s interior. Naturally I started out with a sketch at home, but there were endless variations and modifications as the interior began taking shape.”

The American National Bank was the first avowedly modernist structure in Austin. Equipped with the latest technology, including the first escalators in the city, the building’s style was intended to signal Austin’s transformation into a cosmopolitan urban center. Fogel’s abstract mural lent the building an experimental, au courant feel, which, when it was unveiled, caused the Austin Statesman to report that it “startled” Austinites and “introduced them to the exciting geometrics of non-objective art.”

A detail from Seymour Fogel’s 1955 American National Bank mural

Though the city’s inhabitants were not initially enchanted by Fogel’s mural, Fortune Magazine called it one of “the most distinguished examples of architectural painting” in the country. The Architectural League of New York also selected the mural as part of its 1955 Gold Medal Exhibition.

The American National Bank’s building was eventually sold to the State of Texas and rechristened the Starr State Office Building. It slowly fell into the decay common to bureaucratic edifices and in 2005 was abandoned by the Texas General Land Office. It sat empty for several years and was put up for sale. The Land Office, and a number of other worried parties, feared the building would be demolished, as most developers buying properties in downtown Austin were choosing to tear down existing structures rather than renovate them. They pressed ahead with the sale, however.

Though the building that housed it was in disrepair, Fogel’s mural itself remained in fine condition, aside from the hole which had been stabbed into it to make room for a fire alarm. Robert Summers, an Austin attorney, first encountered Fogel’s mural when the Starr Building was in its “mothballed” phase. He recalls ordering the building’s custodian “to tell me if he would ever see a wrecking ball there.”

Summers explained the mural’s significance, saying, “It’s important, because it was nationally one of the first examples of the integration of art and architecture.”

For its part, the Texas General Land Office recognized the value of the work in its possession; the GLO’s spokesman Jim Suydam said, “[Fogel’s mural is] doing nothing but rising in value.”

A spirited effort to save the mural was mounted by Laura Wiegand; the Director of Programs & Technology with the Texas Commission on the Arts, Robert Summers, and TexasModernArt, an organization dedicated to protecting 20th century Texas Modernist art. By enlisting Texas’s art community in their struggle, Wiegand, Summers and their allies were able to preserve the mural. In 2010, the Starr building was sold to Kemp Properties, which agreed to “include a permanent conservation easement that would preserve the Seymour Fogel Mural in place, in perpetuity.” Kemp Properties now intends to make the former Starr Building “a very energetic, creative center.”

The restored American National Bank mural and Starr Building

The Fogel Murals and the Rediscovery of an American Master

Fogel’s American National Bank mural is now recognized as a triumph of Modernist design and as a pioneering example of the alliance between art and architecture. Its survival demonstrates that Fogel’s works have now become indispensable. Fogel is, through his WPA murals, being rediscovered and assuming a new stature in the story of American Modernism.

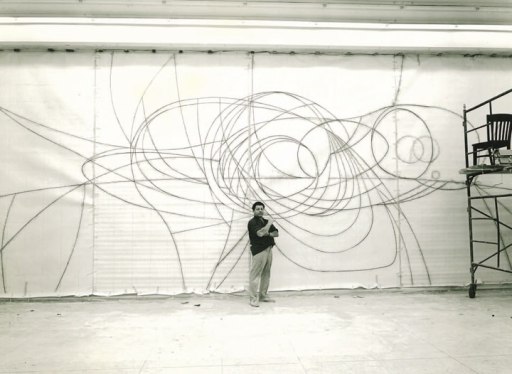

A photograph of Seymour Fogel drawing the “Challenge of Space” mural in Fort Worth, Texas, from around 1964.

In Philadelphia, we have hundreds of murals. I have photographed some of them. and posted them on my blog. The artistic styles are very similar to the images that you have posted here but I and not sure if they are WPA Murals.

Rusty