Yes I am, but on this occasion there was a definite fuzzy-humming-buzzing sound which caught my ear, and then my eye as I noticed this book on the shelf:

Thomas Hill, A Profitable Instruction of the Perfect Ordering of Bees (London, 1608).

And this got me thinking about the significance of bees and how these tiny yet vital creatures deserve far more prestige.

Ok, here are some quick facts. There are over 250 different types of bee in the UK. Of these, 25 are bumblebees and only 1 is a honeybee. Not sure of your honey from your bumble? Me neither, so I’ll buzz it down for you:

Bumblebees are generally the fat, sorry, fuller and furry type and live in nests with roughly 50-400 other bees. They live in the wild so may well be a familiar sight in your garden or the countryside, and they only make small amounts of a honey-like substance (i.e. nectar) for their own food.

Bumblebee, by Richard Holgersson.

The honeybee on the other hand, is one of a kind and smaller and slightly slimmer in appearance, more like a wasp. Honeybees live in hives of up to 60,000 bees and are looked after by beekeepers, though wild colonies do exist. Honeybees store a lot more nectar because of their larger colonies and longer life cycles. It is essentially their food supply for the colder months. This nectar is mixed with a bee enzyme and is later fanned by the bees, making it more concentrated. Both bees are crucial to pollination and both are, sadly, in serious decline.

Honeybee, by Joshua Tree National Park.

In ancient and early modern times, their abundance and importance were widely recognised, particularly with regards to the honeybee. Beekeeping, or Apiculture, if you want to get all technical on me, is the maintenance of honeybee colonies, usually in man-made hives. The production of honey for domestic use is well documented in ancient Egypt, while in Greece, beekeeping was seen as a highly valued and sophisticated industry. The lives of bees and beekeeping are covered in great detail by Aristotle, while the Roman writers Virgil, Gaius Julius Hyginus, Varro and Columella wrote about the art of beekeeping.

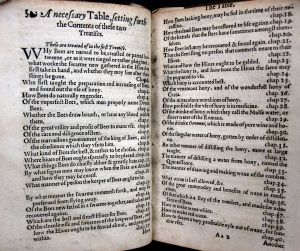

Hill, Ordering of Bees, (1608), table of contents.

Some of their writings formed the basis of Thomas Hill’s A Profitable Instruction of the Perfect Ordering of Bees, the first English manual for beekeepers published in 1568 as an appendage to Hill’s larger work on gardening. His aim was to highlight the benefits of ‘their hony and waxe and how profitable they are for the commonwealth, and how necessary for man’s use’, while his contemporary, Alan Fleming, looked to ‘A Swarme of Bees’ and their behaviour as the perfect example of proper spiritual conduct.

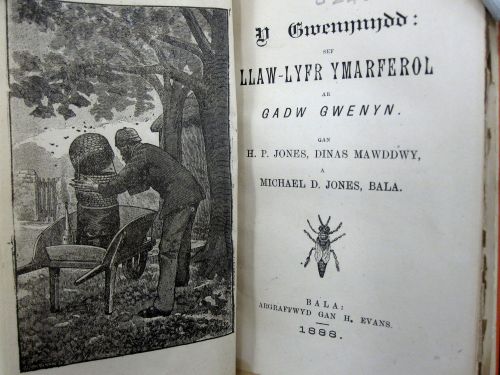

Beekeeping was a common occupation throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Amongst the abundance of popular information contained in contemporary almanacs, advice on aspects of beekeeping is regularly offered. Housekeeping manuals such as such as S. M. Mathew’s Y Tŷ a’r Teulu (The House and Family) (Denbigh, 1891) provided practical instructions on ‘the Care of Bees’ and the best ways to retrieve honey. The most comprehensive treatment of the subject however, is Y Gwenynydd – (The Beekeeper) (or the Apiarist if you still want to be technical about it). Published in 1888, this compact little Welsh book was largely the work of an accomplished beekeeper from Dinas Mawddwy, who was encouraged by his co-author to publish a book on bees for the ‘benefit of our fellow countrymen’, since ‘we did not have one in Welsh’.

Huw Puw Jones & Michael D. Jones, Y Gwenynydd (The Beekeeper), (Bala, 1888).

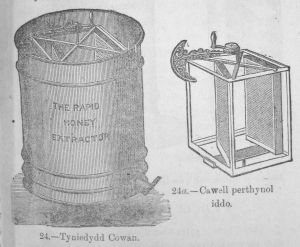

Could this be the first Welsh-language beekeeping manual that we have in our Salisbury Collection? What a buzz! A unique piece of work it definitely is. In Wales, we are told, there is a saying that ‘the bee is such a skilful creature that it can draw honey from a stone’. While the latter is demystified throughout the book which explains the life-cycle of honeybees and the different species, the types of hives used, how to build them and the best methods to extract honey – the bees’ skill is never underestimated.

Image detail of ‘The Rapid Honey Extractor’ from Y Gwenynydd, (1888).

This may explain why bees were as much an object of ‘superstition’ as admiration. It was considered lucky if bees made their home in your roof, or if a strange swarm arrived in your garden or tree, but unlucky if a swarm left. Bees were believed to take an interest in human affairs, hence it was customary to notify bees of a death in the family. The news would be whispered to the hive, and if they were not notified, another death would soon follow. Turning the hive, or tying a black ribbon to it, thus placing it in mourning also had the same effect, and similar customs were observed for happier occasions such as weddings. Writing about these beliefs, the Welsh cleric and antiquarian, Elias Owen, noted that the ‘culture of bees was once more common than it is, and therefore they were much observed’.

Although they may seem strange to us today, such beliefs point to a past awareness of how fundamental bees were to our daily lives and how we should be more attentive to them, more so now that they are under threat. This is why the efforts of organisations such as the Bumblebee Conservation Trust, Pollen8 Cymru, and Professor Baillie and his team at Cardiff University (one of the UK’s first bee-friendly campuses), who are encouraging people to plant more wildflowers to help the bee population and conducting research into the antibacterial properties of honey in the treatment of wounds and the fight against antimicrobial resistance, are so important. Again, this is something that was not lost on our early bee backers. Hill notes the extensive medicinal benefits of honey as a preservative and cleanser, which is good ‘to avail against surfeits’, ‘put away drunkeness’ and to ‘expel humours’, not to mention its ‘profitable’ application to ‘filthy ulcers’; open wounds; ringworm; corns; swellings; ‘dropsie bodies’ (oedema); impostumes (abcesses); earache; dimness of sight and all diseases of the lungs to name just a few. With history and science combined, we can do our bit for the bees and get a very sweet return indeed. And so the moral of this blog post? Well honey, it’s simple. Read a book, plant a flower, and become a lifeline for British bees.