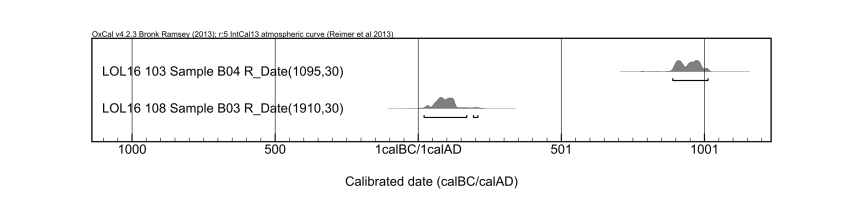

The radiocarbon dates from the Loch of Leys excavation have been returned. The dates indicate evidence for occupation in the 1st-2nd centuries AD and in the 9th-10th centuries AD. Multiple phases of occupation on crannogs is absolutely the norm with these sites being abandoned and then re-occupied two or more times. There is good evidence for use of crannogs in the 1st-2nd centuries AD across Scotland, although this the first evidence for that period in north-east Scotland. In the 9th-10th centuries, there is far less evidence for use of crannogs in Scotland, but the evidence is growing with five sites now have radiocarbon dates from the period, three of those through this project (Loch of Leys, Prison and Castle Islands, Loch Kinord).

This list continues to grow as crannogs in eastern Scotland have been investigated, but for what purpose crannogs are put to in this period remains in question. The excavation of Loch Glashan crannog in south-west Scotland has a hint of occupation in the 9th century in the form of a leather book satchel, possibly indicating use by Christian clergy or monks, but most of the evidence from this site dates from earlier centuries. Crannogs in Ireland have been excavated that date to this period as does the Welsh crannog at Llangorse, and these are normally associated with high status dwellings, although exceptions to this have been highlighted by Christina Fredengren. An intriguing possibility lies in the use of crannogs at this time as assembly sites. Although not a crannog proper (ie. it is a natural islet), the Law Ting Holm in Shetland is used from the 9th century AD as a Viking period assembly site, and excavation there demonstrated evidence for use as a domestic dwelling in the Iron Age and Pictish periods. Archaeological evidence for any site’s use as an assembly site is scant and ephemeral (how to you show archaeologically that people simply gathered somewhere?), but it is a tempting interpretation of crannogs in this early medieval context.

In contrast to the 9th-10th centuries, evidence for the use of crannogs in the 1st-2nd centuries AD is much greater. Most of this evidence comes from south-west Scotland, and not least from Robert Munro. Munro’s 19th century excavations revealed Samian Ware from at least two crannog sites. More recent sampling and excavation has radiocarbon dated phases to the 1st-2nd centuries AD at Barlockhart, Buiston, Loch Glashan, Erskine Bridge, and Dumbuck crannogs. Sites outside of the south-west dated to the period include, Morenish and Tombreck crannogs in Loch Tay, Loch Migdale crannog, Sutherland and Redcastle and Phopachy in the Beauly Firth. Interestingly, these sites span areas that were within regions of high Roman influence in this period (in the south-west) and areas that saw significantly less, such as at Loch Migdale, Sutherland. The Loch of Leys sits between the two. There is the Raedykes Roman camp a few miles down the Dee from the Loch of Leys, but this part of Scotland was never an established part of the Roman empire like parts of south-west Scotland were. This might suggest that building crannogs was not simply or only a direct response to Roman occupation.

Nearly always with crannogs, the history of use is multi-phase, multi-period and difficult to untangle. The Loch of Leys crannog is no exception to this. The aim of the excavation at the Loch of Leys was to establish if there was activity pre-dating the known medieval occupation of the island. That has clearly been answered, and we can confidently say that there were at least three phases of occupation at the Loch of Leys; 1st or 2nd century AD, in the late 9th or 10th century AD, and from the historic sources, occupation in the 13th-14th centuries AD. However, the relatively poor state of preservation on the site means that the stratigraphic relationship between the two radiocarbon dates remains unclear. Further excavation and dating might resolve this question, and better preserved parts of the site may yet be discovered that would yield even better chronological resolution.

Thanks again to those that helped with the excavation – Carly Ameen, Claire Christie, Margherita Zona, Lindsey Paskulin, Peter Lamont, and Gordon Noble. Funding was provided by the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland and the Archaeology Service for Aberdeenshire. Thanks to Thys Simpson and the Leys Estate for allowing and arranging access to site.

Palaeoenvironmental work at the Loch of Leys is ongoing, so stay tuned for more information on the history of the Loch of Leys.

Further Reading –

Llangorse Crannog, Wales

Campbell, E. and Lane, A., 1989. Llangorse: a 10th-century royal crannog in Wales. Antiquity, 63(241), pp.675-681.

Law Ting Holm, Shetland

Coolen, J. , and N. Mehler . 2014. Excavations and Surveys at the Law Ting Holm, Tingwall, Shetland: An Iron Age Settlement and Medieval Assembly Site. BAR British Series 592. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Loch Glashan Crannog

Crone, A. & Campbell, E. 2005 A crannog of the 1st millennium AD; excavations by Jack Scott at Loch Glashan, Argyll, 1960. Edinburgh: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland.

Irish Crannogs

Fredengren, C. 2002. Crannogs. A study of people’s interaction with lakes, with particular reference to Lough Gara in the north-west of Ireland. Dublin: Wordwell.

Radiocarbon Dating Scottish Crannogs

Crone, A. 2012. December. Forging a chronological framework for Scottish crannogs; the radiocarbon and dendrochronological evidence. In Lake Dwellings After Robert Munro: Proceedings from the Munro International Seminar: the Lake Dwellings of Europe 22nd and 23rd October 2010, University of Edinburgh. Sidestone Press.

https://www.sidestone.com/books/lake-dwellings-after-robert-munro