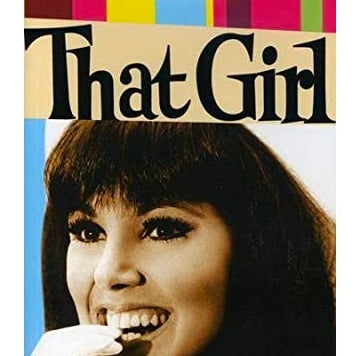

When I was in middle school, a friend and I got caught up in our moms’ television nostalgia and binge-watched That Girl, a 1960s sitcom about the adventures of Ann Marie (Marlo Thomas), an aspiring actress in New York City. Though it was lost on teen soap–obsessed me at the time, the series broke ground by depicting a single woman with bigger dreams for her career than her love life, and with Ann’s dry-witted, suit-wearing boyfriend, Donald (Ted Bessell) acting more as a foil than a destination. Years later, I remember only Ann, striding down Broadway, gazing at skyscrapers, a brassy theme song welcoming her to the city where she believed she could do anything, a well-worn trope today but a milestone then. To understand the evolution of the single sitcom woman—the careerism of Mary Richards, the sexual independence of Carrie Bradshaw, the wackiness of Jess Day—That Girl is the place to start.

A far cry from the just-completed The Donna Reed Show or the fledging The Doris Day Show—which began after Day’s husband signed her contract without her knowledge or consent—That Girl offered audiences a different kind of everywoman. Marlo Thomas, Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique in hand, pitched a series that would neither begin nor end with marriage. Instead, from 1966 to 1971, its protagonist pursued an acting career, fended off her father’s matchmaking schemes, and waltzed off to her happily ever after … of a women’s liberation meeting. At its core, That Girl is about a twentysomething woman navigating New York City. (How appropriate that Thomas would later drop in on Friends as Rachel Green’s mom.) Though parts of the show, like its lack of diversity or its tendency to pair sexual harassment with a laugh track, feel dated now, her crazy adventures and struggles to make ends meet were revolutionary for the time and well worth revisiting.

A 1998 New York Times article described the show as making feminism “approachable and almost, well, cute.” To understand this dynamic, you ought to start with “When in Rome,” the 10th episode of Season 2. A famed Italian director, Vittorio Barrini, spots Ann modeling in a car at an auto show, apparently naked because of the position of the car door. The role of “Angelica” would be perfect for that girl, he says, and the shot zooms in on Ann’s surprised face, the usual “spotted” cold open staple of the series that complicates the idea of the male gaze more often than this scene suggests. Ann’s looks get her the audition, but her acting secures her the gig in her first feature film—but only if she’s willing to play the part nude.

As comical as the characters’ horror (including Ann’s) at performing nude is, the fact that Ann even considers accepting the role sets up a relatively groundbreaking episode, considering the show operated at a time when 25 minutes could entirely revolve around why Donald’s pants are in Ann’s closet. (It’s not because the couple is having sex.) Ann spends most of “When in Rome” telling Donald and her neighbor Ruth the party line, that she couldn’t possibly do it, only to pause and ask, “Could I?,” seeking a permission that neither gives her. This is Ann’s decision alone.

Ultimately, the episode isn’t about modesty so much as a challenge to Ann’s identity: Is she still an actress if she turns down the part? Barrini says no. You’d like to be an actress, he corrects her at one point. Early in the episode, power dynamics like these are made even starker: As Ann reads Angelica’s lines for Barrini in his hotel room, magazine-writer Donald and his co-worker Jerry (Bernie Kopell) wait by the phone. “To them, a pretty, young girl is a pretty, young girl. You know what I mean?” Jerry says, before Ann bursts into the office, hyperventilating. She is too excited to speak; the men, misinterpreting, pepper her with questions about whether Barrini hurt her. The scene is both funny and deeply discomforting, highlighting the ever-present threat of predatory men while playing it for laughs.

But this is the signature battle move of That Girl—the series doesn’t directly call out sexism so much as show Ann wielding the power in the end. Even as Barrini emphasizes what an opportunity he could give her, Ann’s respect for her less glamorous work in minor productions, including as a mop on a children’s program, shines through. And her choice in the end rejects the notion, still present, that a woman must do things she is uncomfortable with to further her career. You’ll have to watch to find out whether Ann gets the part, but know that her inevitable showdown with Barrini is classic That Girl, giving Ann the last word.