Any citizen of the social internet knows the feeling: that irritable contentiousness, that desire to get into it that seems almost impossible to resist, even though you know you’ve already squandered too many hours and too much emotional energy on pointless internet disputes. If you use Twitter, you may have noticed that at least half the posts seemed intent on making someone—especially you—mad. In his new book, Outrage Machine, the technology researcher Tobias Rose-Stockwell explains that the underlying architecture of the biggest social media platforms is essentially (although, he argues, unintentionally) designed to get under your skin in just this way. The results, unsurprisingly, have been bad for our sanity, our culture, and our politics.

On this topic, an increasingly popular one as the social media economy convulses in response to Twitter’s Elonification, the preferred tone is either stern jeremiad or, for the well and truly addicted commentator (usually a journalist), a sort of punch-drunk nihilism much like that of someone who declares he’ll never quit smoking even though it’s going to kill him. Rose-Stockwell, by contrast, keeps his cool, pointing out that social media is full of “angry, terrible content” that makes our lives worse, while carefully avoiding any sign of partisanship or panic.

Outrage Machine: How Tech Amplifies Discontent, Disrupts Democracy—and What We Can Do About It

By Tobias Rose-Stockwell. Legacy Lit.

Slate receives a commission when you purchase items using the links on this page. Thank you for your support.

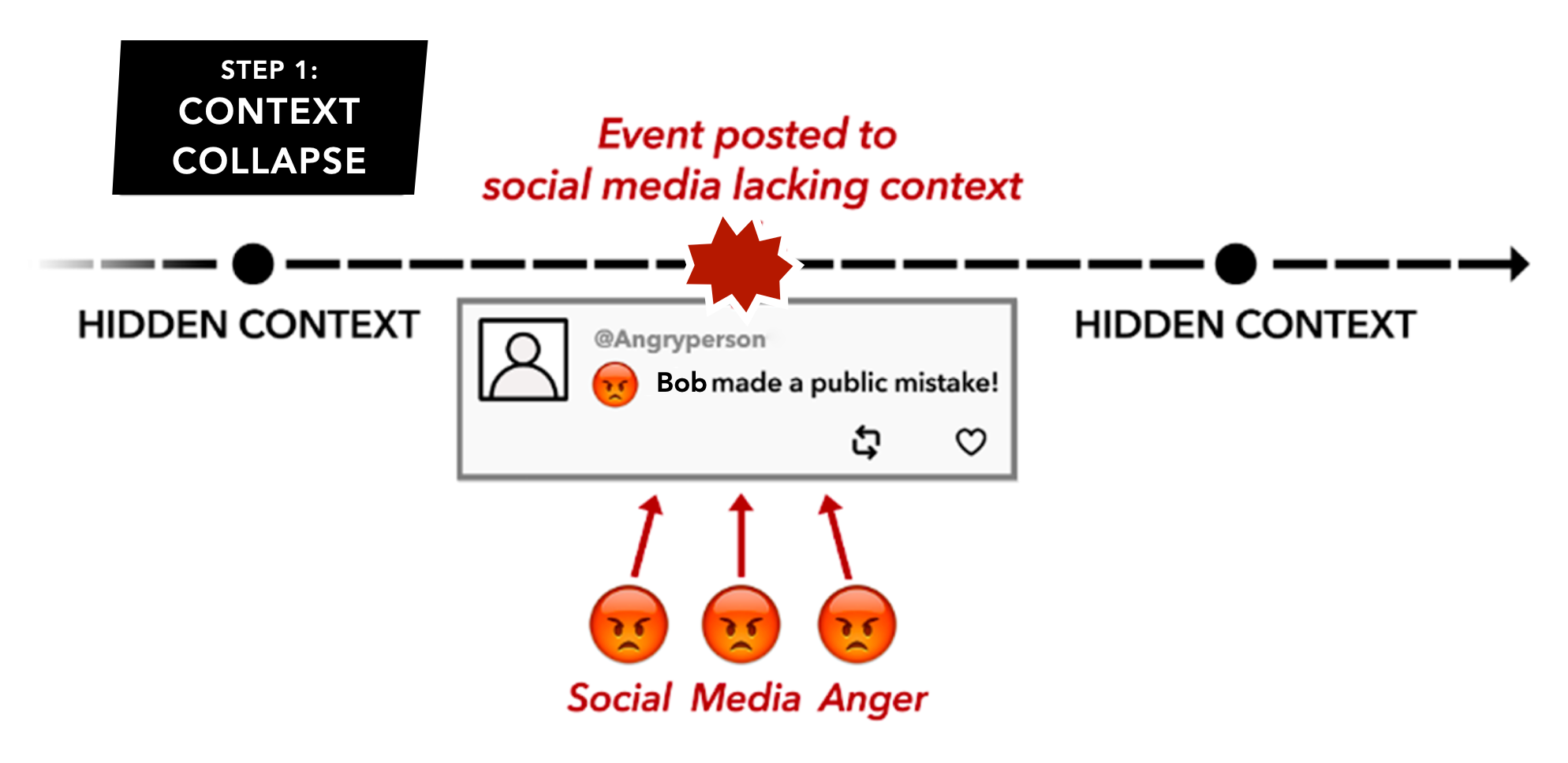

A few chapters in, I began to view Rose-Stockwell’s almost eerily moderate tone as his secret weapon. It deftly avoids the absurdity of being outraged about ginned-up outrage. Outrage Machine reads at times like a textbook, a judicious attempt to illuminate social media and its workings from a certain settled, authoritative distance—not easy to achieve at a time roiled with conflict and alarm. Enhancing this educational aura are the many angry-face-emoji-dotted graphics Rose-Stockwell uses to illustrate his points, some of them genuinely helpful and also unwittingly kind of hilarious:

In this scenario, “Bob” is a hypothetical guy who believes that a woman has cut in front of him in line at the supermarket checkout. He and the woman get into a brief shouting match before she informs Bob that she’d just ducked out of her spot in the line to replace a carton of eggs that turned out to be cracked. He apologizes, and that’s the end of it—except someone recorded the incident on their smartphone, then uploaded only the shouting match, reading all kinds of deplorable motives into it. “The video need only include a hint of cultural asymmetry,” Rose-Stockwell writes:

It may be seen as an angry outburst by a man (Bob) toward a woman (the other shopper). Or a Democrat (Bob) toward a Republican (the lady). Or any heightened reflection of their implied group identity. It can be repackaged as an example of a troubling trend in society. People who feel this way who see the clip now have an opportunity to explain exactly why it’s offensive. They can link it to a larger narrative that may have nothing to do with the actual event itself.

That outrage is often stoked by journalists, who, Rose-Stockwell notes, “are shockingly susceptible to reporting on this kind of thing,” furthering what he calls “trigger chains: cascades of outrage that are divorced from the original event.” Self-described in his author bio as “a renowned media researcher,” Rose-Stockwell is in some respects a journalist as well. But in Outrage Machine he paints himself more as a tech insider who has witnessed the transition from the rosy blush of social media’s initial promise to the red-faced rage of its current discontent while standing alongside friends in the industry who never anticipated how bad things would get. The book opens with an early example of the internet’s positive potential, in the early 2000s, when the 22-year-old Rose-Stockwell was traveling in Cambodia and met a monk who asked him to help restore a broken reservoir that had once served 5,000 farmers and villagers. Rose-Stockwell sent out an email appeal to friends back in the States, a request for donations that spread through listservs and online communities. After seven years of fundraising and hard work, the reservoir was rebuilt.

Rose-Stockwell returned to the Bay Area in 2009, just as the social web was taking off. Friends of his were working at Facebook or for the Obama campaign, and founding sites like Change.org, convinced that new technologies could be used to foster empathy and to power a new form of philanthropy. These people—rather than journalists, who expect more in the way of stylistic panache from a book like this—are the real audience for Outrage Machine. The model is Yuval Noah Harari, whose Sapiens and other titles became all the rage in Silicon Valley about five years ago. Harari describes human behavior and the forces shaping it on a megascale, zooming out to take in millennia and survey revolutions in social life caused by massive changes like the shift from hunter-gatherer subsistence to agricultural surpluses. It’s an approach that focuses on systems rather than individuals, and it holds a lot of appeal for software engineers; it leads to Rose-Stockwell describing the U.S. Constitution, for example, as “the most basic operating code for a democratic republic.”

Books like Sapiens and Outrage Machine supply a substitute for the liberal arts education their STEM-oriented readers missed out on or ignored when they were in college. They just wanted to write code and build tools (and get rich), and only late in the game, once those tools were deployed, did they realize that culture and politics had to be taken into consideration as well. So Outrage Machine offers up streamlined versions of the ideas of Hobbes and Locke (with more of those goofy/helpful diagrams) to explain how you can start out making a platform that you think will democratize communications and undermine authoritarians (see: the Arab Spring), only to end up with a playground for extremists that facilitates the election of Donald Trump. “We assumed that this technology was virtuous in itself,” Rose-Stockwell writes of his cohort in Silicon Valley at the time, “that these tools had their own kind of hidden agenda—one that was inherently beneficial for humanity—regardless of intent.” But capitalism and human nature proved them wrong.

Does it have to be that way? Rose-Stockwell believes that we’re currently in social media’s “dark valley,” a predictable interlude in the history of a new form of media, in which “major disruption” is “punctuated by confusion, disorder, and violence as small groups of activists and innovators exploit these tools to advance an agenda.” In the halcyon early years of the web, tech advocates would often respond to concerns about the internet’s effects by quoting skeptics and doomsayers who’d once denounced the advent of then-new communications technologies like print or radio. These innovations, of course, turned out all right in the end—even eventually came to be cherished by the very fuddy-duddies wringing their hands over the internet.

Rose-Stockwell is not that sanguine, since he believes that this dark valley period and the extremism flourishing in it pose a serious threat to liberal democracies worldwide. But he does believe that social media’s ship can be steadied by better algorithms and moderation, changes that will eventually produce content that users will value as more trustworthy. This is, essentially, what happened to 19th-century American journalism when it emerged from its fledgling years of sensationalism and partisanship. Maybe this will happen before civilization completely topples into authoritarian nationalism, but that’s a huge responsibility to leave in the hands of people who are currently scrambling to understand the social and political forces they’ve unleashed—especially when there are so many financial incentives to indulge humanity’s worst impulses.

Because our attention naturally locks on content that inspires negative emotions like anger and fear, those urges are currently baked into social media’s algorithms. And the more we engage with that content, the more mad and scared we become. Rose-Stockwell doesn’t believe that social media merely surfaced the preexisting but previously unknown objectionable opinions in our fellow citizens. He argues that the conflicts and flame wars and cancellation campaigns of social media actively drive users to extreme positions, where they become ever more dug-in. Any sensible adult knows that calling someone names and yelling at them about their poisonous ideas do not actually inspire a contrite reconsideration of those ideas—quite the opposite. But few of us are sensible when embroiled in an online debate, and the lectures we dispense aren’t really meant to educate our opponents—they’re tacitly aimed at a real or imagined audience of the like-minded ready to congratulate us on how right we are.

Exacerbating this situation is a small proportion of users who have learned how to game this system by posting content that is incendiary enough to rile people up without violating a platform’s terms of service. Rose-Stockwell calls these users “line steppers,” but he also sometimes refers to “conflict entrepreneurs,” a term I first encountered in Amanda Ripley’s immensely helpful 2021 book, High Conflict: Why We Get Trapped and How We Get Out. These are canny individuals who know how to set off and perpetuate a certain kind of conflict to raise their own profiles and influence.

For years, I couldn’t stop myself from engaging with, and being enraged by, all of them: the conflict entrepreneurs, the idiots with bad opinions. It’s taken a sustained act of willpower to transform my own relationship with social media. I found Ripley’s High Conflict revelatory precisely because it allowed me to see how I could de-escalate the fruitless conflicts that made my own online life so poisonous. It required identifying not the characteristics of certain kinds of posts—the ingenuity of conflict entrepreneurs is fathomless, as are the bad opinions of idiots—but the way their posts and comments make me feel. Now when I feel that particular flavor of nettled testiness, the compulsion to conclusively put down some rando who clearly has no idea what he’s talking about? I know that social media has activated some primitive part of myself I’ve got to resist for the sake of my own peace of mind.

The urge to indulge this outrage can seem overpowering, and I still sometimes find myself succumbing to thoughts like “I can’t wait to see all the awful replies to that tweet.” Still, more often than not, I can turn away, and my life has become infinitely better for it. I’m not sure I believe that institutional change alone is enough to keep each new social media platform from falling prey to the worst side of human nature. Is it possible for us, the users of the internet, to learn how to simply not go there? I hope so, because that may be what it takes to get us out of Rose-Stockwell’s dark valley and back into the sun.