House Speaker Nancy Pelosi announced Tuesday that she was initiating a formal impeachment inquiry into President Donald Trump after allegations that he withheld military aid from Ukraine to pressure President Volodymyr Zelensky into investigating former Vice President Joe Biden and his son Hunter. The story of Trump’s phone call with Zelensky came to light because of a whistleblower complaint filed by a member of the intelligence community, and the fight over access to the report helped reinvigorate calls for Congress to begin impeachment proceedings.

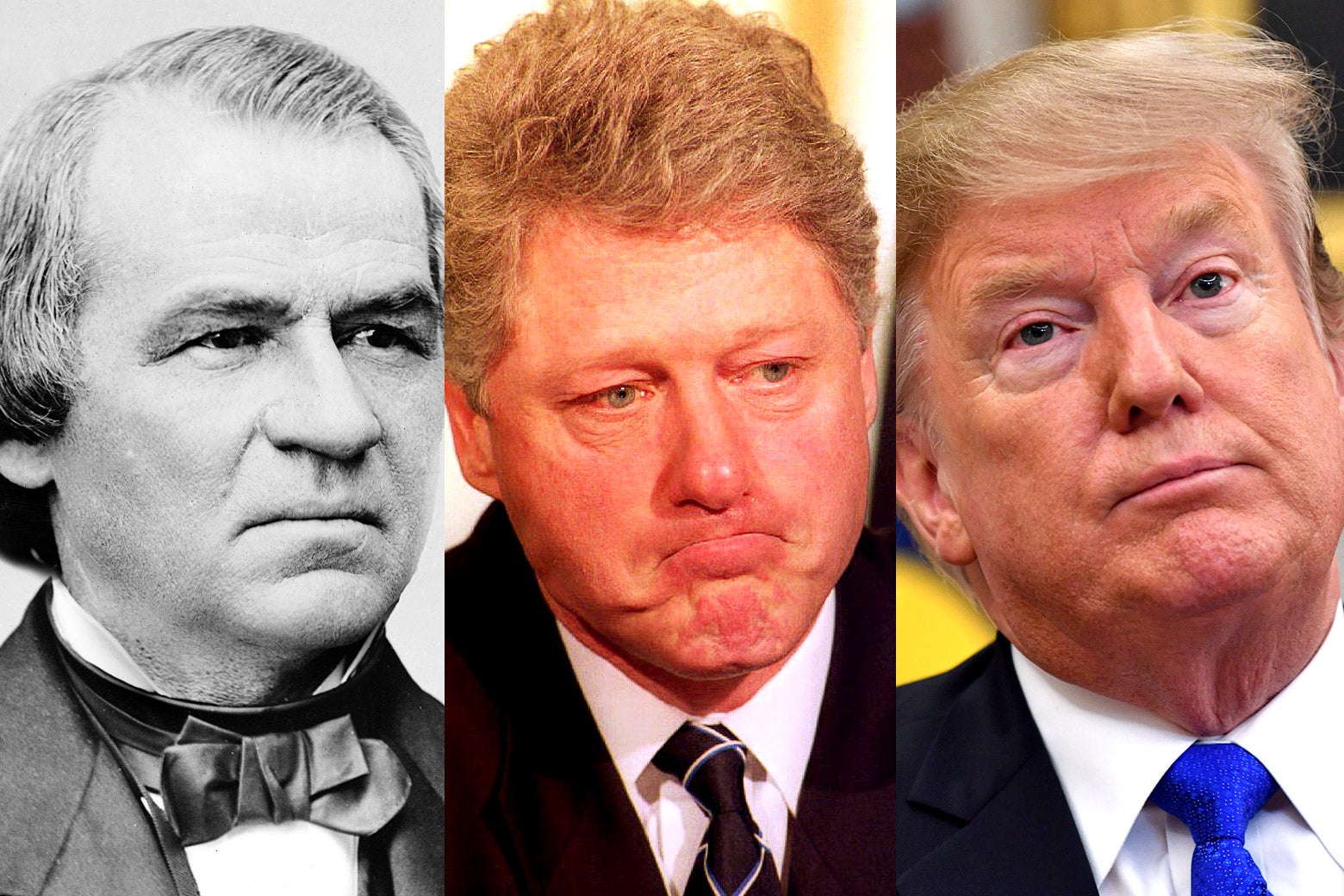

Congress has never successfully removed a sitting president. Andrew Johnson in 1868 and Bill Clinton in 1998 were both impeached but ultimately not ousted, while Richard Nixon’s resignation in 1974 allowed him to avoid near-certain impeachment. The difficulty of the task is in large part due to the requirements set by the Constitution, which are paradoxically both exceedingly demanding and frustratingly vague.

Here’s what it would take for Congress to remove Trump from office.

Step 1: Introduce an Impeachment Resolution

The road to removal begins with any representative in the House calling for impeachment proceedings to commence. In July 2017, California Rep. Brad Sherman, Texas Rep. Al Green, and Tennessee Rep. Steve Cohen jointly introduced an impeachment resolution, which Sherman then re-introduced this January. It’s then up to Pelosi as House speaker to decide whether to move forward and direct a committee to begin an impeachment inquiry. She did that on Tuesday.

Step 2: Draft Articles of Impeachment

Pelosi will then assign a committee to take the lead in the inquiry. The House Judiciary Committee handled impeachment inquiries for Nixon and Clinton, and a special committee stepped in for Johnson’s impeachment. Early reports indicate Pelosi has asked six committees currently investigating Trump on other matters to also look into his dealings with Ukraine and then submit their findings to the House Judiciary Committee.

The Judiciary Committee would then decide if there is enough evidence to draft the articles of impeachment, which are essentially the specific charges against the president. Article II of the Constitution states that a president “shall be removed from office” for “treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.” The definition of “high crimes and misdemeanors” is absent from the Constitution, which has stirred dissension during previous impeachment episodes. The criteria for such offenses therefore essentially boils down to whatever a particular Congress collectively decides it is.

Step 3: Impeach the President

Once the articles are complete, the Judiciary Committee has traditionally voted on which ones they want to introduce to the full House. Committee approval requires more than half of its members’ support. The Judiciary committee currently has 17 Republicans and 24 Democrats, so yea votes from 21 Democrats would be enough pass the articles. During Nixon’s impeachment proceedings, the committee approved three articles, but he resigned before they got any further in the House.

In order to formally impeach the president, a simple majority of the full House must vote for one or more of the articles. The House passed two articles for Clinton, including perjury and abuse of office, which was down from the 11 that special counsel Kenneth Starr had recommended. Representatives passed 11 for Johnson, however, which mostly involved his disregard for the recently passed Tenure of Office Act. The House currently consists of 198 Republicans, 235 Democrats, and one Independent. Assuming that an impeachment vote would occur after the special election in January to fill the vacant seat in Wisconsin’s 7th Congressional District, it would require approval from 218 members to impeach Trump.

Step 4: Hold a Trial in the Senate

It’s then up to the Senate to decide whether to force a president from office by holding a trial. The Senate serves as the jury, the House as the prosecutors, the president’s lawyers as the defense, and the chief justice of the United States as the judge. This is where things get procedurally dicey since the Constitution does not lay out any rules dictating how the court is supposed to be run. Both times the Senate has held such a trial, the body passed a new resolution that determines these rules.

The Senate therefore gets to decide if and how many witnesses can be deposed, whether the depositions should be live, the length of the trial, and other procedural matters—a challenging and potentially dubious task, given that the Senate also decides the outcome of the trial. As Bob Barr, who served as House manager during the Clinton impeachment proceedings, told the New York Times, “The jury in a criminal case doesn’t set the rules for a case and can’t decide what evidence they want to see and what they won’t.” That an ostensibly apolitical process doesn’t preclude such a potential conflict of interest for Senate partisans is notable.

Predictably, Republicans and Democrats fought over the shape of the trial for Clinton, particularly on whether to allow witnesses to testify. The Senate eventually allowed House prosecutors to question three of the 15 witnesses they wanted to depose: Monica Lewinsky, Vernon Jordan Jr., and Sidney Blumenthal. Prosecutors acknowledged that witnesses would not likely reveal any new information during the hearing, but said they nevertheless wanted to give senators an opportunity to assess the credibility of Lewinsky and others in person.

In the case of Trump, it wouldn’t be a stretch to imagine partisans quarreling over whether the full Senate should hear live depositions from the Ukraine whistleblower or Hunter Biden.

Step 5: Make a Final Decision on Removing the President

After the trial proceedings conclude, the Senate then votes on each article of impeachment. Removing the president requires a two-thirds majority on one or more of the articles. Such a move would be unprecedented in American history: Johnson, after an 11-week trial, escaped removal by one vote in 1868; while Clinton, following a five-week trial, remained in office after the Senate voted not to remove him, with a more comfortable, double-digit margin.

In Trump’s case, obtaining a two-thirds majority vote would be an even taller order with Republicans in control of the Senate. There are now 53 Republicans, 45 Democrats, and two left-leaning Independents in the Senate, so at least 20 Republicans would need to defect to depose Trump. Given congressional Republicans’ track record of ducking their duty when it comes to Trump, it would take a bipartisan miracle to clear a path to the president’s removal.