Killian Mullarney

When I first heard Fea’s Petrel in 2004, the occasion was touched with sadness. Arnoud van den Berg and I had been travelling across the Cape Verde Islands, some 750 km from Cap Vert in Senegal. We had been on Raso, the uninhabited island that is home to the world population of about 100 Raso Larks Alauda razae. Suddenly we felt very isolated when, on returning to our lodgings on São Nicolau, news reached us that Arnoud’s mother was dying. We had to wait three days before there was a plane to take us off the island. Arnoud returned to the Netherlands and I decided to continue the trip on my own, flying to the largest island Santiago, then on to the island of Fogo.

Fogo means fire in Portuguese, and the island is an enormous, cone-shaped volcano, twice the size of Vesuvius. Seen from the air, it is 25 km across, with its northern half dominated by a massive crater, 8 km wide. The western walls of this ‘caldeira’ soar to 900 m while on the east side, they have collapsed into the sea. In their place stands a new volcanic cone, Pico Novo, which at a height of 2829 m is the highest point of the island.

From the airport, I negotiated a ride in the back of a pickup. The road climbed the arid outer slopes from the town of São Filipe, and crossed the caldeira wall at its southernmost edge. The youngest lava, black, jagged and dusted with green, yellow and red minerals, was just nine years old. Older flows were browner and eroded, with subtle gradations. Overwhelmed, I thought about my own mother, a geographer and geologist who died when I was 17. I found myself looking at the crater through her eyes.

Under the cliffs on the west side of the crater floor or Chã das Caldeiras there are two villages, Portela and Bangaeira. Their soil is highly fertile, and various crops are grown, including vines, coffee and figs. The small, French-run guesthouse was full when I arrived, so instead, I stayed in one of the local homes built with breeze blocks of black lava, which blend in perfectly with the landscape. In the not so distant past, everyone lived in round huts with cone-shaped roofs, but very few were left in 2004.

Portela village and the west wall of the caldeira, Fogo, Cape Verde Islands, February 1986 (René Pop). 04.005.MR.14505.03 was recorded along the caldeira walls.

In 1861, a French nobleman, Armand de Montrond, landed on Fogo. Why he came is a mystery, but a popular story has it that he was on his way to Brazil, distraught after his best friend was killed in a duel. He found Fogo very much to his liking, and adapted quickly to island ways. Local men typically had two or three wives, and Montrond evidently surpassed them. He is said to have sired a hundred children, and now almost everyone living in the crater bears his surname. It seems that Montrond became so popular, he could afford to be choosy, as there is a surprisingly high proportion of attractive girls among his descendants. Many have fair eyes and blonde but tightly curled hair, mixing northern European and African features. Elsewhere in the Cape Verde Islands the African influence is stronger, and the people are descended from victims of the slave trade who never made it to the Americas. For all his joie de vivre, Montrond was far from idle. He improved the lives of the poor peasants in many ways, for example by introducing several new crops. Fogo’s fruity and rather strong ‘manicon’ wine is made from vines he imported.

Because my visit was primarily to record petrels at night, I had plenty of time to relax during the day. On one of my first walks through the two villages, a middle-aged Montrond named Tito invited me in to taste his wine and coffee. I stayed there for hours, chatting to him and his daughter Carmen in something resembling French, sipping the sweet manicon, and eating delicious goat’s cheese. The next day I climbed Pico Novo with a guide called Ilias, and I was able to peer into the steaming new crater. Its steep slopes are covered in fine volcanic ash, like powdery black snow. Coming down, you can run fast, and fall down with little risk of injury. If you ignore the whirring of your legs, the sensation is much like skiing, and the 1000 m descent is over in no time at all.

The crater on Fogo has long been known as a breeding site for Fea’s Petrel. A friend from Lisbon, Manuela Nunes, told me inspiring stories about hearing them calling from the crater walls several years ago. When Cornelis Hazevoet wrote The birds of the Cape Verde Islands in 1995, Fogo was thought to be their most important breeding site. In early 1998, the Freira Conservation Project from Madeira joined forces with Hazevoet and the RSPB to survey Fea’s in the Cape Verde Islands (Ratcliffe et al 2000). They not only listened for calls and searched likely habitat for nests, but also made enquiries among the local people. Many were familiar with the bird, but as one person on the north-eastern island of Santo Antão explained, the general policy was one of “case e ase” or “catch it and roast it”

(Zino 1998). The expedition searched Fogo between 11 and 31 January. Colonies were found in three areas, and local inquiries revealed the probable locations of another two. The largest two, with a combined total of about 35 pairs, were found in the western walls of the crater, above the village of Bangueira. Most were thought to be just under the top, but two dry river valleys under the cliffs also held about two pairs each. In one of these, a Fea’s was found incubating under a boulder (Ratcliffe et al 2000).

As I was hoping to record Fea’s Petrels calling in flight near their nests, the dry river valleys sounded like the best place to start. I searched them thoroughly in the daytime, sniffing and scouring among the boulders. All I could find were a few very old feathers, probably more than a year old, but still retaining a faint fishy smell. Otherwise, there were no signs of petrels at all. Fears expressed by Ratcliffe et al in 2000, who had found three adults dead outside their burrows, were probably justified: “On Fogo, all the colonies in the valleys and outside the caldeira are easily accessible to both humans and cats so predation there could continue until the population becomes limited to the two cliff sites above the caldeira”.

CD1-05: Fea’s Petrel Pterodroma feae Bangueira, Fogo, Cape Verde Islands, 20:00, 21 February 2004. Moaning calls of two individuals flying along caldeira walls more than 2000 m above sea level. The calls were recorded from more than 500 m below. Background: crickets, distant dog and its echo. 04.005.MR.14505.03

After dark, I climbed a huge pile of fallen volcanic rubble, about 160 m above the crater floor, hoping to record petrels still breeding way up in the walls. I was careful to stay within earshot of the valleys too, in case there were petrels there after all. As I sat and waited, listening to crickets and the distant sounds of the village, I imagined Fea’s Petrels ascending 2000 m up from the sea. Would they fly into the wind, crossing arid farmland and the southern foothills, or soar above the forested northern slopes of the volcano? On their arrival, the acoustics of the caldeira must be a delight to these petrels. I only heard a handful that night, hundreds of metres up near the top of the caldeira walls. ‘Gon-gon’, the local name, means something like ‘ghost’, and their sounds are hauntingly beautiful (CD1-05).

According to the 1998 survey, there were also some small colonies in old lava flows on the outer slopes of the volcano, with nest cavities among basalt rubble and tunnels on gently sloping ground. If only I could find one of these colonies, perhaps I might be able to record Fea’s Petrel at close range after all? On my second night, I decided to try and find the one at Cabeça do Turil, since this place was marked on my 1:60 000 map (AB Kartenverlag 2002).

Shadows lengthened as I walked to the northern edge of the crater, and by the time I started the 900 m descent through some fairly dense forest, Grey-headed Kingfishers Halcyon leucocephala were heralding the end of the day. Although marked on the map, the forest trail was partly overgrown. Descending was not difficult, but I was going to have to climb back up the steep slopes later in the night. I began to regret drinking manicon wine with Carmen and Tito again that afternoon. Several times, without any warning from the map, I arrived at a fork, where I tried to identify the least overgrown path. I left my GPS running, so I could retrace my steps if I got lost.

When I heard dogs barking somewhere further down the narrow path, I considered heading back. Could these be strays, or was there someone else deep in the forest in the middle of the night? I soon realised that the steep, overgrown path was leading me to a couple of simple houses. With plenty of noise and a “boa noite”, I made myself known to several children and two older women. I doubt they had ever seen anything like it; a tourist emerging from the forest at night, carrying all manner of strange gear. I was taken into one of the houses to meet some kind of forest guard. He had been at the grogue, and was completely drunk, but not unfriendly. He bellowed like someone who does not realise he is a bit deaf. Or more likely, he thought I was the deaf one, because I could not understand what he was saying. All I could say to him were the words “gon-gon” and “Cabeça do Turil”. To my relief and amazement, he seemed to understand and we reached a deal. For a small sum I hired his two teenage sons to guide me to the spot.

Without their help, I am certain I would never have found it. After several forks where we took the more overgrown path, the forest eventually began to thin out, and I heard the acoustic change to a rocky one. A fairly broad section of path crossed an old lava flow. I searched for an open spot with a wide acoustic ‘view’. Just as I was starting to unpack my gear, I heard familiar moans approaching from below. A Fea’s Petrel came hurtling past, calling loudly several times as it passed right over my head, then dropping in pitch as it flew uphill in the direction of the caldeira. It was the only one I heard that night. After waiting at least an hour for more, I headed back up towards the caldeira with nothing to show for my long trek. The GPS proved its worth, and I managed to get back up the forking path without getting lost. It must have been about 03:00 when I finally hit the sack.

Monte de Sentinha, São Nicolau, Cape Verde Islands, 19 March 2007 (René Pop). Fea’s Petrels Pterodroma feae breed among the pinnacles left of centre.

A week earlier, during one of the long nights when Arnoud was waiting for the plane home, we had visited a colony on São Nicolau. The colony is located on pinnacles of rock near the middle of the island, on the east side of Monte de Sentinha. However, the terrain is difficult and dangerous, and the petrels can only be heard from a distance. In 1998, the survey team had estimated its size at about 10 pairs but, happily, we found it to be considerably larger. On 15 February 2004, the calling rate at Monte de Sentinha was much higher than a week later on Fogo. I had a second opportunity to visit this colony on 19 March 2007, with Killian and Pim Wolf, a friend from the Netherlands. Because we were a little late in the season, I expected we would hear rather few calls. But the average count for the best 10-minute period was 22 calls a minute. This matches the main Zino’s Petrel colony on Madeira on a good night, where there were about 40 pairs in 2006. So Monte de Sentinha could be one of the largest colonies in the Cape Verde Islands.

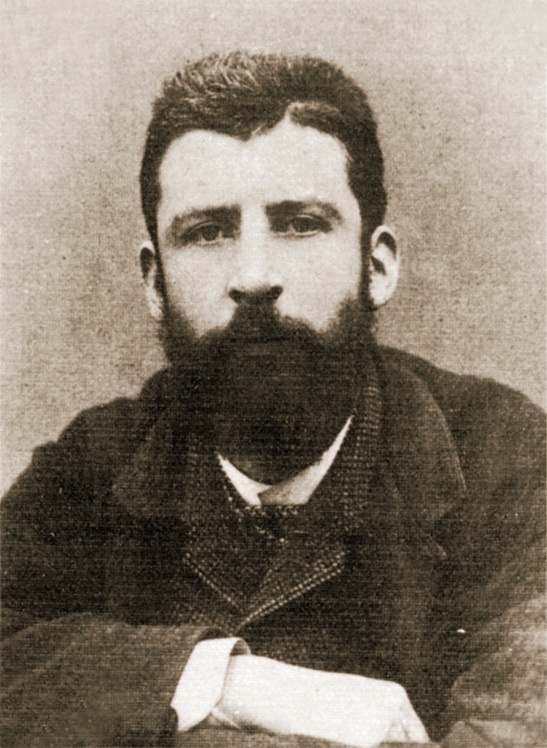

São Nicolau was the island where Leonardo Fea collected the original type specimen of Fea’s Petrel back in 1898. An assistant at the Natural History Museum in Genoa, Italy, his reputation was established when he returned from an expedition to Burma in the 1880s with new species of thrush, viper, tree rat and muntjac, all of which were later named after him. Health problems determined that his next expedition should be to somewhere with a drier climate, and he visited the Cape Verde Islands in 1897-98. It was his friend the taxonomist Tommaso Salvadori who named Fea’s Petrel in his honour (1899, 1900). But the discovery of Fea’s actually goes back 130 years earlier, to the first voyage of Captain Cook. Apparently, in October 1768, a Fea’s was collected at sea by D C Solander, nearly 900 km south of Fogo, and about one third of the way from Guinea Bissau in Africa to Natal, Brazil (Bourne 1957, 1983). Although the specimen was lost, it could later be identified thanks to a drawing by Sydney Parkinson (Lysaght 1959).

Leonardo Fea, who visited the Cape Verde Islands in 1897–98 (date and photographer unknown)

In February 2007, having longed to go back to the Cape Verde Islands for three years, I persuaded my wife Ilse to come with me to Santo Antão, where the 1998 survey had found the largest breeding population. The colony that Ilse and I visited was at a location called Topo de Biôrro, and the difficulties encountered in making the recordings are typical of the frustrations that bird recording affords.

As so often, the name was not marked on our map, but thanks to approximate co-ordinates supplied by Frank Zino, and a thorough study of satellite imagery on the internet, we had narrowed it down to within a kilometre or so. Passing several big villages, climbing a pass and descending through rugged mountain scenery towards the north-west coast, it took us three hours to drive to our destination, the last part climbing in four wheel drive. The track suddenly ended next to a house, in a desert plateau of reddish soil and rock called Chã Dura, about 1000 m above sea level. At this time of the evening, only mist rising from the sea betrayed the location of a huge ravine, like froth spilling out of a cauldron. The sun had already set, so we had less than an hour to find the best spot for recording. At the house where we parked our jeep, we learned that Topo de Biôrro was the name of a small but fairly obvious summit nearby, with almost sheer cliffs rising above the mist on one side. When we stood peering over the edge 10 minutes later, we could see little of the huge ravine, the Ribeira de Agua Nova, but from the pathetic sound of a bleating goat, far below us, and dogs barking at their own echoes, the majestic scale was clear. Just before it became too dark to see, the mist finally cleared.

Fea’s Petrel Pterodroma feae, São Nicolau, Cape Verde Islands, 24 March 2007 (Killian Mullarney)

The first Fea’s Petrel called exactly an hour after sunset, but it soon became apparent that most of the action was happening over on the other side of the gorge. I made some recordings from where I was, then tried to make my way round the clifftop in the dark. It was almost impossible to use a torch without setting off a Mexican wave of barking dogs at scattered houses all around the top of the ravine. Moving around in the dark, close to the edge of the ravine, was thrilling to say the least. Eventually, we came to an area where the calls seemed to be louder and there was less wind. Just at that point a lighting generator started up about two kilometres down towards the sea. As long as it kept droning on, I could forget about making any recordings. But an hour after they had started, the Fea’s were silent anyway.

After a couple of hours failing to sleep on mats outdoors in the cold, we tried to sneak back to our jeep without alerting the nearest dog and waking everyone up. We failed. When the dog finally stopped barking, we hardly dared to move a muscle, in case the jeep’s creaking suspension might set him off again. Quiet voices could be heard talking in the house. Although we had taken care to make our intentions clear, sleeping in the jeep had not been one of them. Once or twice, the man of the house came out and paced about a little. Eventually, he came over to the jeep and started talking to us excitedly in Creole. He seemed to be offering his services for everything imaginable, guiding us to the top of the island, to even remoter places in the north-west, into the ribeira. At one point I understood something about cheese, then off he went. We settled down to try and sleep again, but within minutes he was back with some goat’s cheese, which we bought to calm his nerves (it was delicious!). Eventually we managed to communicate that we would like to catch some sleep. By now it was about 05:00. I had left the window slightly open for fresh air. Far off, I heard a Fea’s Petrel calling, then another, the start of the pre-dawn exodus. I got my gear ready again, braved the dog, and headed back off to the cliff top. The calling was over by the time I got there, and in the remaining darkness until dawn, all I heard was a single Boyd’s Shearwater Puffinus boydi, a long way off down the gorge.

Fea’s Petrel Pterodroma feae, São Nicolau, Cape Verde Islands, 24 March 2007 (Killian Mullarney)

Fea’s Petrel Pterodroma feae, Fogo, Cape Verde Islands, 21 March 2007 (Jacob Gonzáles-Solís)

After a day of resting, trying to catch forty winks in scarce shadows, I prepared for a second attempt. I set up the microphones on a corner of the cliff top, jutting out into the ravine. Listen to the series of spectacular recordings (CD1-06 to CD1-08), and you will hear an awesome vocal and aerobatic performance. It is hard to resist ducking when the Fea’s Petrels come very close. They were very hard to see as they shot past in the dark, but by listening to wingbeats and moans in the recording, you can follow their trajectories.

These fantastic birds were using the entire upper airspace of the ravine, up to about 50 metres above the edge of the surrounding plateau. Every call was given by a Fea’s Petrel in motion. As you listen to CD1-06 through headphones, you can follow a high and a low caller, alternating moans as they twist and turn around the gorge. Three kinds of wing sounds can be heard: rapid beats at a rate of five or six per second (eg, at the start), whistling or hissing glides, which change rapidly in pitch due to the Doppler effect (eg, from 0:08) and, occasionally, a short, quick series of claps (eg, at 1:10)

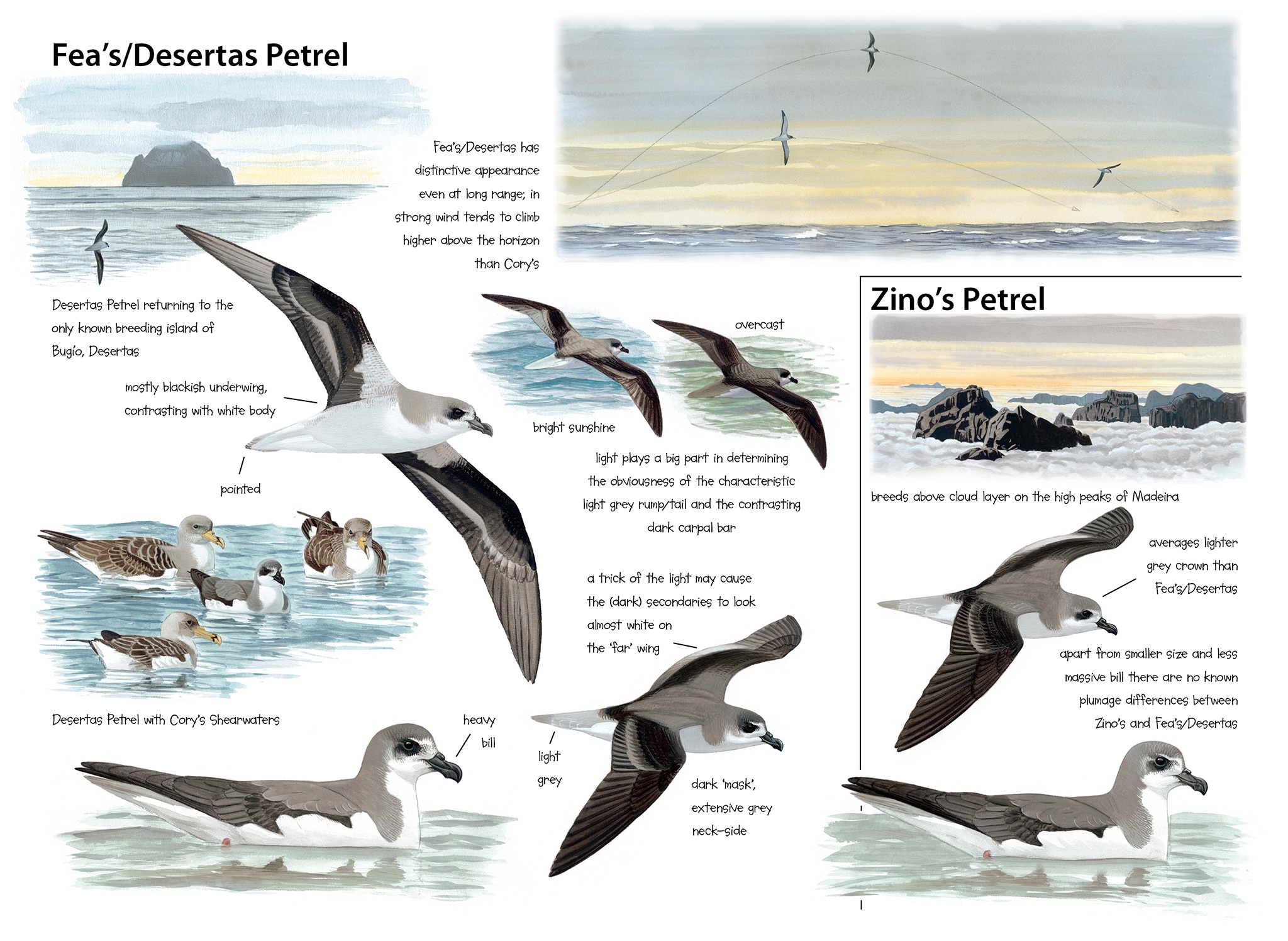

By comparing the loudness of wings and voices, you can hear that Fea’s Petrel moans are not really that loud. On the whole, they are very similar to moans of Zino’s Petrel, although the starting frequency averages slightly lower in Fea’s. In the sonagram, you can see the loudest calls of CD1-06.

CD1-06: Fea’s Petrel Pterodroma feae Chã Dura, Santo Antão, Cape Verde Islands, 20:25, 18 February 2007. Moaning calls of a presumed courting pair in spectacular nocturnal display flights, using the entire airspace of a precipitous gorge. 070218.MR.202509b.01

In the next recording, CD1-07, you can hear a series of high moans at the start, possibly all given by the same bird. Suddenly, 18 seconds into the recording, you can hear a low moaner passing very close to the cliff top where the microphone was positioned. In the second half, low moans dominate, sometimes more than one at a time. They vary in length from less than one second to more than two seconds. The average is somewhere in between, much the same as in Zino’s Petrel.

CD1-07: Fea’s Petrel Pterodroma feae Chã Dura, Santo Antão, Cape Verde Islands, 20:32, 18 February 2007. Moaning calls of several displaying individuals, predominantly high-type at first, then nearly all low-type towards the end. 070218.MR.203235b.01

At 0:49 in CD1-07, there is a moan that ends with a very obvious –wik or rising squeak. Here, the pitch rises almost instantaneously from less than 1 kHz to more than 4 kHz. More of these squeaks or inflections can be heard in CD1-08. This recording starts with a presumed pair chasing each other while exchanging high and low moans. A high moan ending with a -wik at 0:36 is immediately answered by a low one with a similar ending at 0:41. Most moans of Fea’s and Zino’s Petrels lack this squeak, which makes it all the more noticeable when it occurs.

High and low variants of Fea’s Petrel moans differ in the same way as in Zino’s Petrel. In the sonagram of CD1-08, you can see that low moans of Fea’s also have subharmonics, and a harsh, chaotic ending, while high moans only have subharmonics briefly at the end. The high moan in the sonagram also shows some frequency modulation towards the end, a feature that Fea’s seems to show less often than Zino’s. Perhaps it is slightly easier for Fea’s, a heavier, stronger bird, to control the pitch of its moans, avoiding ‘vibrato’ effects caused by wing action.

CD1-08: Fea’s Petrel Pterodroma feae Chã Dura, Santo Antão, Cape Verde Islands, 20:18, 18 February 2007. Moaning calls of several displaying individuals, some with rising –wik inflections at the end. At 0:36-0:41 high and low inflected moans are exchanged between two petrels. Background: dogs barking. 070218.MR.201849a.01

During a total of eight nights spent at Fea’s Petrel colonies, I have only once heard a whimpering call, like the ones that can frequently be heard from Zino’s (eg, CD1-03 & CD1-04). The only other sound that I have sometimes heard in Fea’s, apart from moans and wing sounds, is a kind of sneeze. In the quiet of the Ribeira de Agua Nova, it could be particularly clear when a Fea’s flew past at close range. An example can be found at 0:08 in CD1-09, where it sounds a little harder and less sneeze-like than usual. In retrospect, I discovered that Zino’s ‘sneeze’ too. If you listen very carefully, you can hear a couple of examples in CD1-01 and CD1-02.

CD1-09: Fea’s Petrel Pterodroma feae Chã Dura, Santo Antão, Cape Verde Islands, 20:00, 18 February 2007. A ‘sneeze’ of an individual flying past at close range. 070218.MR.195643.01

To summarise, moaning calls of Fea’s Petrel are similar to those of Zino’s Petrel. Moaning calls of Fea’s average slightly lower-pitched, and Fea’s seldom uses the high-pitched whimpering calls that are common in Zino’s. Moans of both petrels descend fairly steeply in pitch, and about a third end with a rising squeak. What is most interesting is that the same cannot be said for moans of Desertas Petrel, from the colony on Bugio near Madeira.