WAY-OUT POLYNESIA: The Forgotten Marquesas Islands

(This story appeared in the Dallas Morning News, Toronto Star, Salt Lake Tribune, Buffalo News, Grand Rapids Press, Maine Sunday Telegram)

Photo: On the Marquesas Island of Hiva Oa, Clovis Gauguin, the great grandson of the artist Paul Gauguin, poses at the grave site of his storied ancestor. Photo: Susan Farlow

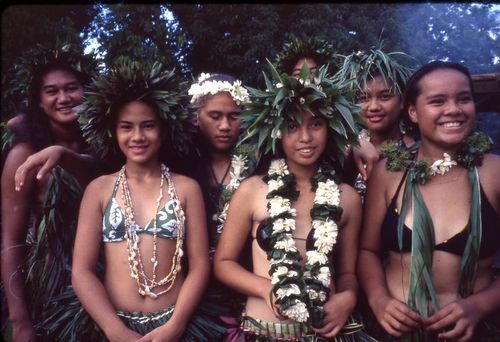

Photo: Local girls in traditional clothes, in the town of Atuona, a place artist Paul Gauguin once called home.Atuona is on the Marquesas Island of Hiva Oa. Photo: Susan Farlow

Cruising with descendants of artist Paul Gauguin in the forgotten Marquesas, the world’s most remote islands: Home of tattoos, taboos, ghosts and reformed cannibals.

by

Susan Farlow

It was 6 a.m., and my eyes were glued to the shore as our ship dropped anchor off the Marquesas Island of Nuku Hiva. There’s nothing like arriving at a place with a cannibal past to put you in an observant mood. And Nuku Hiva, like several more of the rugged Marquesas Islands we would soon be visiting, had once been a hotbed of cannibalism and human sacrifice. And so, I was antsy to get a look at the island.

Trouble was, the island didn’t want to be looked at. Fog veiled the place. What I could barely make out was a jungly green mass which, here and there, erupted into saber-toothed mountain peaks. The whole island jutted straight out of the sea. This might be French Polynesia, but there was not a beach to be seen. Soon the fog was joined by torrential rain, and then visibility was zilch. It was like the island was whispering, “Want to see me? Come a little closer.”

Our voyage had begun four days earlier when we cast off from Tahiti, the largest island of French Polynesia (pop.: 130,000), and after a one-day stop in beach-blessed Bora Bora, we sailed for the Marquesan archipelago. Some 950 miles northeast from Tahiti, the craggy volcanic Marquesas are the most remote islands on earth, home to forbidding scenery, mysterious tiki gods and a few of the strangest customs on Earth.

And it’s just such remoteness that pulled at explorers, artists, and writers such as Herman Melville and Robert Louis Stevenson, who came to the seldom-visited Marquesas, looking for inspiration in an untouched place, for a heaven on earth. Among these dreamers was the French artist Paul Gauguin, who lived out his final years on the Marquesas Island of Hiva Oa (he died in 1903), and in whose honor our sleek white cruise ship, the new m/s Paul Gauguin, was named.

And I had to wonder: What are these islands like today? Paul Gauguin’s offspring were wondering the same thing. And onboard this voyage, some 65 Gauguin family members, along with several hundred other passengers, were soon going to find out.

By 10 a.m., the rain had stopped on the north coast of secretive Nuku Hiva, and passengers were deposited at the tiny village of Hatiheu whose unpaved main drag lasted for all of about 50 yards, a pretty stretch edged with a robin’s-egg blue schoolhouse, a dreamy white church, a restaurant and a little general store.

But when I reached the far edge of the village, the whole atmosphere went from pretty to primeval, as I began a slog up a winding muddy path. Fifteen minutes later, I found myself at a scene described in the dusty tomes of 19th-century explorers: A performance of ancient dances in a sacred stone ceremonial plaza where Marquesans once worshipped their gods and ate their enemies.

Soon, war cries and drums tore through the humid air. Grimace-faced stone tiki gods stood sentinel over their realm. Surrounded by jungle gloom, the site had all the mood of a lost city.

Talk about feeling like Indiana Jones in the Temple of Doom.

Within these sacred districts, the ancients had to mind their Ps and Qs. Lots of behaviors were taboo. And, I learned from the ship’s archeologist, Mark Eddowes, the very word taboo originated in Polynesia (from tabu, meaning forbidden) . One thing, though, that was not taboo for the men in the old days was devouring pua oa or “long pig” (humans, to you and me).

So when it was time for the famous “Dance of the Pig” to be performed, I wondered just what pig they were referring to. The oink-oink variety was, according to the archaeologist, “almost deified in the Marquesas” for its “mana” or supernatural power. It was also welcomed on the menu.

But once the leaf-clad dancers got underway, the grunt-like chants and on-all-fours choreography pretty much pointed to the short pig as the inspiration. Another clue that we were among friends: once the performances ended, all the dancers posed for endless photos, smiling to no end. Not one person asked for a tip or a photo fee. A strange custom.

In the early afternoon, just when the sun had muscled its way out from behind the black clouds, our ship set off for the south side of the island. The Marquesas lie just eight degrees south of the Equator. A fact I easily believed. Even though the temperatures were reported to be around 80 degrees, the islands still felt like a steam bath.

And so, after a hot and sweaty time on shore, it seemed like paradise to me to return for a wallow aboard the m/s Paul Gauguin, with its pool, four bars, a spa, pampering staterooms, fine food, observation lounge, boutique, plus pretty much every bell and whistle a super-luxury ship normally offers.

Herman Melville, the great American writer (1819-1891), wasn’t nearly so happy with the conditions on his ship, the whaler Acushnet. So, in 1842, the 22-year-old Melville jumped ship at the Nuku Hivan town of Taiohae, which happens to be our next port of call.

Nowadays, besides being the administrative center for all the Marquesas and its largest town (pop. : 1,700), Taiohae also happens to be the place to find the of bright lights of the archipelago. That is, the Marquesan version of bright lights. Which means –besides government offices and a post office – it boasts a bank, a handful of stores, a few eateries and lodgings, and maybe a mile of paved road.

But the town is full of charm, and as I dawdled around, I ran into Clovis Gauguin, one of the ship’s passengers and Paul Gauguin’s great- grandson. He had just made a hike for a bird’s-eye view of the mountain-encircled harbor.

“I can’t believe how beautiful this place is. I’m already out of film,” said the 50-year-old bearded Clovis, a likeable fellow who works as a headmaster in a school in Denmark and dabbles in the arts as both a painter and musician. “And you know, I am a hopeless Deadhead,” he laughed, referring to his passion for the Grateful Dead band.

Herman Melville couldn’t stop praising the beauty of the place either. (One of his gushes: “Nothing can exceed the imposing scenery of this bay.”) Seems that even being held hostage by the island’s fiercest cannibal tribe, the tattooed Typees of the Taipivai Valley, hadn’t left a bad taste in his mouth about the island. Eventually, he made an escape and even ended up writing his first book, Typee (1846), based loosely on his experiences.

Some 150 years later, my shipmates and I are champing at the bit to see this Taipivai Valley, where Melville was held captive. For Melville, the journey from the port to the cannibal valley was a bushwhacking scramble through mountainous, overbearing jungle terrain. My group was in a jeep, rolling with the punches on a rutted muddy “road,” also through mountainous, overbearing jungle terrain. Along the way, wild horses grazed along the corkscrew track. Waterfalls splashed.

After two hours of bone-rattling riding to traverse a mere 10 miles, we stopped at an overlook, and the ship’s archaeologist pointed below, “There is the famous Taipivai Valley, where Melville lived for six weeks.” A bay cut up into the trenchlike valley, giving it the dramatic look of a fjord. Wispy clouds fringed the tops of mountains. Smoke was curling up from the valley. “What do you suppose is cooking?” quipped a shipmate.

Well, not much of anything is going on nowadays. Only about 450 folks live in the valley. And things have tamed down. Once in the village, the only thing I saw blazing was a couple color TVs inside pastel-painted houses. These days, when you come calling at Taipivai Valley, schoolkids want to talk your head off.

And, all that smoke? Coconut meat, one of the island’s major products, was being dried over a fire. Only this and nothing more, I was told.

One old tradition, however, is undergoing a revivial these days: Tattooing. This art originated in ancient Polynesia (as did the word, tatu), but nowhere was tattooing as developed as in the Marquesas. “In the old days, by the time a man died,” explained ship archaeologist Mark Eddowes, “he was thoroughly tattooed, including the eyelids, tongue and genitals.”

Must have had some mighty good reasons, huh? Decoration was one. But mostly, it was to communicate: Your tattoos made you an open book, telling the story of your life. Chiefs and warriors sported so many tattoos that from a distance their bodies appeared to be blue. Then in the mid-1800s, missionaries banned the practice.

Nowadays, you’ll find many Marquesans once again wearing tattoos (usually symbols of tikis, turtles or other ancient motifs), though the full-body jobs still seem to be out of vogue.

At 10 p.m., the ship pushed off from Taiohae. Before long, the wind was howling and the seas choppy. (How choppy? Swells were so strong, in fact, that two ports had to be cancelled the next day because landing by tender boats would have been unsafe.)

This is not the kind of seas I expected in the South Seas. But then the Marquesas are a different world from the other island groups of French Polynesia: Different language, different weather, even the people look different. The men are incredible hulks, just whoppers. “Magnificent physiques” logged Captain James Cook, the great 18th century explorer.

By now it had been hammered home to me that a ship is the easiest way to visit these distant and inaccessible outposts. For one thing, there is no jet airport on any of these islands.

For another thing, because these brooding islands are so inaccessible,

mass tourism has yet to arrive. Which means no tour buses (hardly even any paved roads), no tourist traps, and really no hotels. Pretty much the only lodgings available are small pensions, bungalows for rent, or rooms in private homes. Traveling by ship, we have been hauling our hotel with us, along with a couple of gourmet restaurants.

And so by the time we arrived at Hiva Oa, the island Paul Gauguin spent his last days, I was starting to think that maybe a whole lot hasn’t changed in the Marquesas since Gauguin was here.

When we landed at Atuona (pop.: 1,300), the island’s main town and where Gauguin lived from 1901-1903, the small dock was jam-packed with smiling locals. A young woman in a banana-leaf skirt lassoed me with a lei, then went on to do the same to each passenger from the m/s Paul Gauguin, a vessel dedicated to the fellow whose art revealed her island to the world.

Not too far away, Gauguin the painter rests in Calvary Cemetery, overlooking the bay (and Gauguin the ship). This has to be one of the world’s most beautiful graveyards. Before long, the grave and simple tombstone (“Paul Gauguin — 1903") was surrounded by 65 family members –pretty much the entire Gauguin clan which ranged from infants up to 80-somethings—who had traveled here from Scandinavia to pay their respects on this day, which happened to be the 150th anniversary of his birth.

Traveled from Scandinavia, note, not France. The Gauguins had journeyed mostly from Denmark and Norway, with a few from England. It’s a long story, but here’s the gist: When money became tight in the mid-1880s, Paul Gauguin sent his Danish wife, Mette, and their five children to Copenhagen to live with her relatives. The Gauguin family tree, thus, went on to sprout mostly in Scandinavia. As one of Paul’s great-grandsons told me: My name is Gauguin, Clovis Gauguin, but I do not speak French.”

Up at the gravesite, I noticed that not one of the locals had joined us there for the speeches. It was only later I learned from a 1957 book by anthropologist Dr. Bengt Danielsson that the islanders never go up there. Because they believe ghosts inhabit the cemetery.

All I know is that many current guidebooks claim the Marquesans are firm believers in tupapaus (ghosts), convinced that spirits haunt the ancient ceremonial grounds and are touchy beings which, when insulted, will take revenge. Even the carved tikis are said to be alive and often vindictive. And I recall something my guide in Tahiti, who was not from Polynesia but Paris, said: “Do not ever move a tiki. It is bad luck.”

In any case, where were all the villagers? Turns out, they were all in the main part of the town, knocking themselves out preparing a kaikai (feast) in the traditional underground oven for the cruise passengers. While the short pig cooked, I tackled the hoopla-packed village square, peeking into the little museum and a replica of Gauguin’s last home, a bamboo-thatch roost he called the “House of Pleasure.”

(By the way, this wasn’t the only home Gauguin knew in French Polynesia. Before coming to the Marquesas in 1901, he lived some eight years on Tahiti.)

But of all the Marquesas Islands, Fatu Hiva was said to be the place where folks lived the most traditional lifestyle. The smallest (4 miles by 9 miles) and most remote of all these remote islands, Fatu Hiva, total pop. 641, was our next stop.

So far the haunting scenery of the Marquesas had been a photographer’s dream, but the setting of Hanavave, one of Fatu Hiva’s two villages, really took the prize as a film gobbler. Soaring volcanic pinnacles tower over a bay harboring a few yachts. Dark clouds fringed the mountain peaks. Yet directly above the sea, the sky was so bright blue and the clouds so white, your eyes hurt to look at it.

The village is tucked so far back into a steep valley, you can’t get a good look at it until you’re nearly on shore. Am I intruding, I wondered as I started off down the village lane. I passed the schoolhouse, and in seconds, the lane was filled with kids who begin the chant of, “Hello. How are you? I am fine. Thank You.” Over and over… When my ears can take no more, I hold up my camera. Chant stops. Everyone poses. Again and again …

Farther along, an old woman motioned me onto her porch. She shuffled into the house, then returned, proudly carrying her prized possession: a huge old book, yellowed with age, prepared by a German anthropologist to document the ancient arts and tattoos of these islands. Lying on a table were tapa, cloth made from the bark of trees and an ancient craft that today is pretty much practiced only on Fatu Hiva.

Eventually, I caught up with the ship’s archaelogist who was leading some passengers to the old stone ruins of a chieftan’s home. It was a site nearly swallowed up by jungle. Such overgrown ruins dot the Marquesas, and this has to be one of the few places left in the world where you can still feel like you’re the first person to discover a forgotten ancient city.

Before our voyage ended back in Tahiti, the itinerary would include visits to Rangiroa, a Robinson Crusoe isle that’s the world’s second largest atoll, followed by jag-peaked Moorea, an island so beautiful James Michener wrote, “to describe it is impossible.”

As we had sailed from island to island, we had been coming upon one pocket of paradise after another, just like the explorers and escape artists of the 18th and 19th centuries. But, of course, times change. Nowadays, you won’t end up on the menu.

MARQUESAS ISLANDS AT A GLANCE

The haunting (and perhaps haunted) Marquesas Islands are a fascinating handful of specks in the vast Pacific. A few facts:

Location: Most isolated inhabited islands on earth, located in the South Pacific Ocean, about halfway between Australia and the U.S.

Population: About 8,000. The Marquesas are the least populated of French Polynesia’s five archipelagos. Of French Polynesia’s total population of 220,000, only 3.5 % live in the Marquesas.

Land Mass: 10 main islands, with only six inhabited. Total land area is about 385 square miles. Nuku Hiva is the largest Marquesas Island, about 12 miles by 9 miles or 127 square miles.

Local Name of the islands: The Marquesan people call their island group Te Henua Enana, meaning “The Land of Men.”

Pioneers: Marquesans were the Polyneisans who originally settled Hawaii.

Political Status: Overseas Territory of France. Claimed for France in 1842 by Admiral Abel Dupetit-Thouars.

Languages: Marquesan and French.

2 notes

realusernameunknown liked this

wwwaboutcom-blog liked this

wwwaboutcom-blog liked this susanfarlow posted this