There are oodles of advantages to having a diverse workforce, but, as inBeta founder James Nash points out, you can’t simply take your homogenous workforce, add diversity, stir and hope for the best.

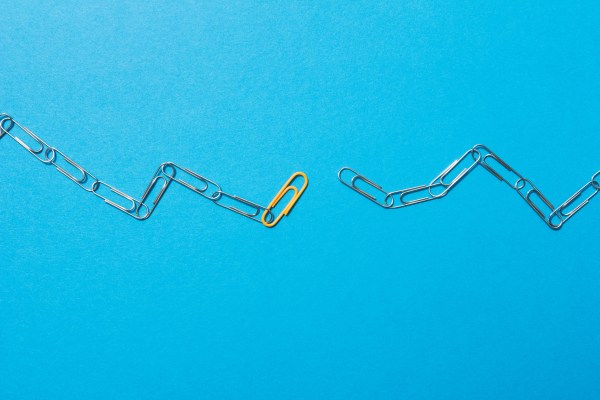

Often, something subtle gets in the way of diversity at startups: Companies depend on employee referrals in the beginning, but if a startup’s makeup is already not diverse, referrals aren’t going to change that.

That’s for startups. In the world of venture capital, things are more pronounced: A warm introduction is the only way to get in front of investors at many VC funds. That’s great for people who are already hooked into the startup ecosystem, but you don’t have to look for very long to realize that this is not a very diverse group of people.

“We’d love to hear from you. The best way to reach us is through someone we mutually know.” A VC firm's website

For many companies, employee referrals are one of the main ways to attract new talent. That’s all good until you stop to think who your newest hire is likely to know best. It doesn’t take many rounds through that particular mill until you end up with a relatively homogenous group of people with similar education, socioeconomic backgrounds and values.

If that’s what you’re optimizing for, great! Well done. If it isn’t, perhaps it’s time to stop being lazy and question why warm intros are still common practice.

My question has long been: What are you optimizing for by relying on referrals? If you spend some time thinking about that, I bet you’d unearth some uncomfortable unintended consequences.

Let’s talk about what we can do about it.

The situation in VC

If you read any guides about startups or raising money (including my own, although I also try to cover cold emails and cold intros), you’ll find that you need a “warm introduction” to land a meeting with a VC. Given the above parallel with hiring, that’s a problem.

After I moved to the U.S. in 2016, I ran into this problem myself. I realized that my biggest challenge was that I was busy building my companies instead of focusing on networking. That was great for my companies but not that great for fundraising. I knew maybe 20 venture investors, but none of them were very interested in the space I was in and fundraising for.

The tyranny of warm introductions is where the diversity question becomes particularly painful for the VC community. There are some notable exceptions, but in my research, I realized that the vast majority of VCs don’t post their email addresses on their websites.

Instead, they’ll write, “We’d love to hear from you. The best way to reach us is through someone we mutually know,” or “To tell us about what you do, get an intro from one of our portfolio companies,” or “If you can’t get a warm introduction to a VC then how on Earth are you going to [be successful].”

Yes, those are all real quotes from venture firms you’ve probably heard of.

I get it. VCs are inundated with emails and people pitching companies. You have to filter the bad from the good somehow, right? I get that, but at the same time, maybe it’s time to take a good, hard look at the collateral damage VCs are causing in the process.

In other words: Who are you filtering out when you optimize your funnel for people who have access to those types of introduction networks?

In effect, the VC is saying, “Unless you know people who know us, we don’t want to talk to you.” That doesn’t fly if you are trying to build a diverse employee base and it probably isn’t going to if you’re trying to fund a diverse group of companies.

So how do you solve this?

At the heart of it, VC firms are not meant to be investing at the middle of the bell curve of opportunity. The big returns are at the edges: the weirdos, the outliers, the people who’ve spotted something nobody else has. The very best founders are a perfect melange of delusion, obstinacy and oddity — you need a little bit of all of the above to be successful as a founder.

But the corollary is that these folks may hail from anywhere and they may not be in a VC investor’s network.

I can think of a number of ways to solve this. One way would be to tackle this as a data problem and start solving it with technology. Here’s how I would go about it, but there are probably far better ways:

- Clearly state your investment thesis on your website. Include which stage(s) you invest in, which market(s) you target and what you are looking for in an opportunity.

- Have an open channel for pitch submissions. A web form would be perfect here.

- Get back to founders as quickly as you can. We’re running a marathon at sprint-speed here. I can’t tell you how much rather I’d take a hard “No” over a fluffy “Eh, maybe?”

About that web form: That’s your opportunity to leverage technology and filtering. You could even use a bit of AI here if you wanted to get really fancy — I bet there are ways to filter and pre-select so you can at least ensure that startups fall within the investment thesis. If they don’t, that’s an easy “No.”

Yes, you will get a lot more pitches, but you can filter most of them out right away.

Filter for location, round size, investment terms, the market, founding team, traction, market size, partnerships, customer growth … whatever you care about. Use the form to automatically reject founders that have companies you wouldn’t be interested in by definition.

Of the remaining inbound requests, get one of your associates to read every submission and create a tool that makes it easy to give macro-driven responses.

Best of all: If you make it take five minutes to fill in the form, founders will start to read your investment thesis more carefully. Five minutes isn’t a huge amount of time for a founder who is following a targeted pitch plan that has 10 investors they want to talk to. But it will drastically decrease the founders taking a spray-and-pray approach.

It’s easy to do, helpful to founders, makes you more approachable, and it means that potentially great opportunities that you otherwise wouldn’t have even seen don’t slip through the net.