I took a walk from Danby Beacon to Lealholm Moor to have a look at a Ring Cairn that I had recently read about.

The wide track from the Beacon is made of slag, the slag would probably have been brought from the furnaces of Teesside during the early days of WWII when a large radar installation was built on the moors. Ironstone travelling from Rosedale and the Esk valley down to the furnaces of Teesside with iron-rich slag returning to the moors.

A rainstorm blows into Great Fryup Dale from the high moors

The storm tracks along the Esk valley, the sun briefly follows behind.

At the side of the track a gorse bush has grown a hedge around its base, a prickly windbreak for itself and the moorland sheep

On the rigg the thin moorland soils offer little, this is compounded by the regular burning and draining of the moors, ensuring that very little apart from heather and a few grasses can thrive. In times of increasing climate instability and the loss of native species, the management of grouse moors is coming under increasing pressure to change its ways. Stanhope White once called the moors ‘a man made desert’.

A moorland cross base and cradle, the remains of Stump Cross. The cross was located at the junction of 2 medieval trackways, Stonegate and Leavergate.

The cross base sits at the foot of Brown Rigg Howe, a Bronze Age Round Barrow located on a small hill. The barrow is intervisible with a number of other prehistoric monuments including mounds on the other side of the Esk Valley.

On top of the barrow is a steel plate, a base plate of a military searchlight, used for guarding the nearby Radar station during WWII.

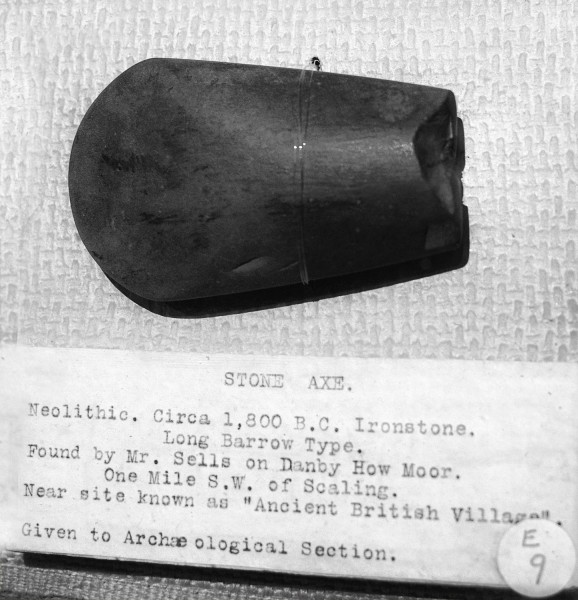

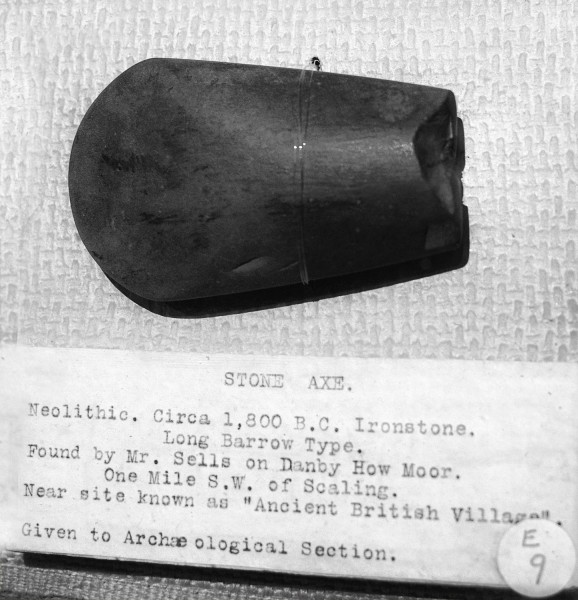

The Brown Rigg barrow was opened by Canon Atkinson of Danby, he found a cremation burial and a stone axe made of basalt. A number of stone axes have been found locally including one made from Ironstone, it is now in the Whitby Museum.

The Brown Rigg barrow was opened by Canon Atkinson of Danby, he found a cremation burial and a stone axe made of basalt. A number of stone axes have been found locally including one made from Ironstone, it is now in the Whitby Museum.

Rabbits have made the mound their home, their paths revealed where the heather has been burned-off.

I walk on to the next barrow, a gamekeeper cruises by in his large 4×4. The keepers work for the Baron of Danby, Viscount Downe owner of the Dawnay Estate. The Dawnay estate website states that the Barons ancestors came from Aunay in Normandy. I would like to think that a number of my ancestors lie beneath the earth and stone mounds of the moors.

I walk on to the next barrow, a gamekeeper cruises by in his large 4×4. The keepers work for the Baron of Danby, Viscount Downe owner of the Dawnay Estate. The Dawnay estate website states that the Barons ancestors came from Aunay in Normandy. I would like to think that a number of my ancestors lie beneath the earth and stone mounds of the moors.

I arrive at the Ring Cairn. As with most surviving North Yorkshire moorland Ring Cairns there is very little to be seen, the 14 meter diameter ring can just be made out in the heather.

What draws me to these places is not necessarily the physical remains of the monuments but the opportunity to walk and observe their viewsheds, seeing how they sit in the landscape and speculate on their relationship with the many other prehistoric monuments of the area. Lines of mounds running across the moors and along the coast, marking the trackways and territories of our ancestors.

intervisibility/alignment – monuments – invasion beacons – radar stations – trackways

axe – ironstone – scoria

A great article on the WWII radar site at Danby Beacon http://liminalwhitby.blogspot.com/2012/12/danby-beacon.html

Heather Burning Article Yorkshire Post March 2020

The Brown Rigg barrow was opened by Canon Atkinson of Danby, he found a cremation burial and a stone axe made of basalt. A number of stone axes have been found locally including one made from Ironstone, it is now in the Whitby Museum.

The Brown Rigg barrow was opened by Canon Atkinson of Danby, he found a cremation burial and a stone axe made of basalt. A number of stone axes have been found locally including one made from Ironstone, it is now in the Whitby Museum.

I walk on to the next barrow, a gamekeeper cruises by in his large 4×4. The keepers work for the Baron of Danby, Viscount Downe owner of the Dawnay Estate. The Dawnay estate

I walk on to the next barrow, a gamekeeper cruises by in his large 4×4. The keepers work for the Baron of Danby, Viscount Downe owner of the Dawnay Estate. The Dawnay estate