Plants in the Magnoliophyta Division may also be called Angiosperms or flowering plants, they include grasses, palms, oak trees, orchids and daisies. Magnoliophyta is the only division that contains plants with true flowers and fruits, and all plants in this division use those flowers and fruits to reproduce. It is not known exactly when flowers first appeared, but definitely by 125mya and probably as far back as 160mya.

Flowers have proved to be an extremely successful adaptation, and despite its recent appearance, Magnoliophyta is by far the largest and most diverse plant division with over 250,000 different species and 500 families. (For comparisons to other divisions and their sizes see here)

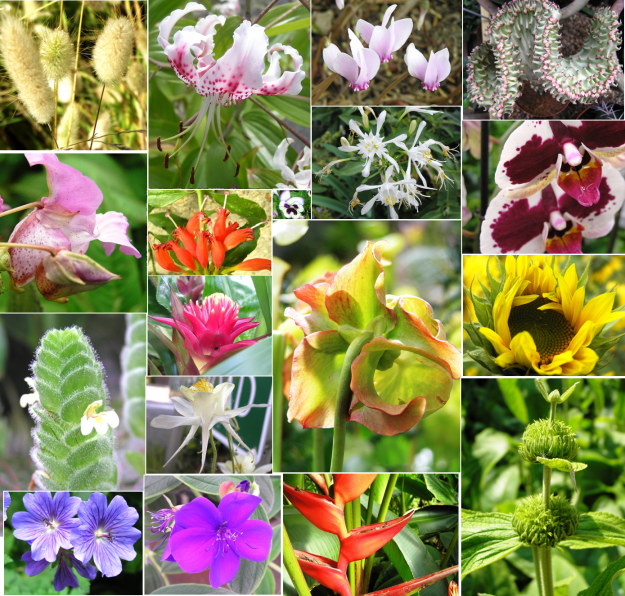

Flowers

In Magnoliophyta, flowers replaced the cones of more primitive plants, as a means of reproduction. Some flowers are brightly coloured, have a scent or produce nectar in order to entice animals to pollinate them, but others use wind or water and, having no need to draw attention, are barely noticeable.

Fruit and what that really means…

All plants in this Division produce fruits of some kind, even though what they produce may not be easily recognised as fruit. The botanical definition of a fruit is a matured ovary (the ovary is the female part of the flower that contains the ovules which become the seeds once fertilised), this includes peppers, tomatoes, aubergines, nuts, peas, wheat grains, but not apples or rhubarb. There is another meaning for the word fruit, which is culinary and refers to a sweet part of a plant that is eaten, this is the more familiar term and includes rhubarb and apples, but not tomatoes and nuts, etc. ‘Vegetable’ is only a culinary term, referring to parts of a plant used in savoury cooking, it may refer to any part of the plant: leaves (lettuce) flower buds (broccoli), stems (celery) or roots (carrots) and has no botanical equivalent.

Classification

Being such a large and interesting division means that the classification of Magnoliophyta has received more attention and undergone more changes than any other division.

How Many Flowering Plants Are There?

It was believed for some time that there were over 400,000 flowering plants, but it turns out that many species of plant (not known as yet how many) have actually been named twice or even three or four times. The binominal naming system (using two Latin names, eg Helianthus annuus) was designed to make plant naming international and straightforward, but with people all over the world discovering and naming plants and no comprehensive way of cross referencing them, we have ended up with a lot of confusion. Now, partly due to the international power of the internet, serious attempts are being made to work out how many actual species there are and to remove duplications. The Plant List is a collaboration between a number of botanical gardens around the world and has an impressive online collection of these names.

DNA Alters The Family Tree – Cronquist to APG III

Before DNA testing was possible (or DNA was known about) plants were collected into families, classes and orders according to detailed studies of how they looked.

Over the past few hundred years there have been many different classification systems, but one of the most commonly used and straightforward was the Cronquist System, devised in 1968. This System grouped plants into families, with the families grouped into orders, orders then grouped into sub classes and sub classes grouped into two classes: monocotyledons and dicotyledons. However, with genetic testing, it has been found that many of these groupings were wrong. A new system, called APG (Angiosperm Phylogeny Group), was introduced in 1998, but has subsequently been updated twice since then and will no doubt change in the future.

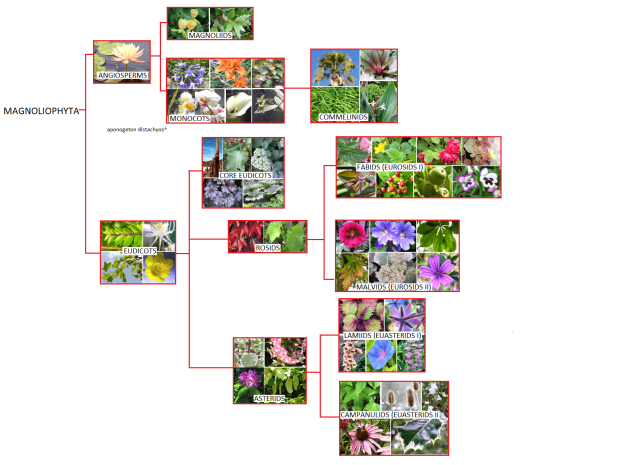

Frustratingly, what was once a very neat and straightforward system of classification has become an unwieldy, confused and messy system, because nature is never neat. The new system, called APG III, does not use classes and subclasses, instead it groups orders within clades, nested within other clades, nested within other clades; with some families not fitting into any clade at all.

The following diagrams are an attempt to show the changes in a simple manner, using images of plants to represent different orders and showing how those orders have altered their connection to others. It is clear that some assumptions were completely wrong, for example some dicots are more closely related to monocots than other dicots; the buttercup is not kindred with the water lily; cacti are more connected to Heuchera than originally thought and oak trees are closer to Euphorbia than London planes.

Note: I was unable to take photos of a tulip tree or Rhododendron in flower, so used photos I got online from here: Rhododendron and tulip tree

It was also fairly tricky to find all the necessary information about where plants appear in the Cronquist system, if anyone spots any faults, please contact me at the email to the right. Most of my information came from Wikipedia, and from here

To enlarge the key click the thumbnail