I feel that I ought to say something about the unlikely PR mess that the UK’s Arts and Humanities Research Council has got itself into, but I’m not going to, for three reasons, in fact four. Firstly, it is very unclear just what the heck is going on there; secondly, others have already writ what can be writ better, not least Gesta and that famously Edgy Historian, Guy Halsall, and you can follow the links there (which, as here, have usually come from JPG, who clearly has a future as a news analyst at somewhere like Reuters if the Vikings ever run out). Thirdly, and most cowardly of me, the current director of the AHRC is deeply implicated in whatever it is, and is also about to become my boss in some distant sense, so I don’t feel that analysing her current actions and research on the open web will do me any long-term favours. And the fourth reason, the afterthought, is the one I should always remember, the Bede Principle: “it may not yet be known what should be written of these things, until they have reached their end”.1 So instead I’m going to write about my current research, even though the same could be said of that, and the ways in which I do it.

Monastery of Sant Pere de Casserres, Osona, Catalunya

Those of you who know my work will realise it involves quite a lot of charters. For my thesis I read, I think, about 3,500 charters in printed editions, though rather fewer in the original. Aware of that latter weakness, when I made the first trip to Catalonia recorded on this blog, I sought out the parchments of Sant Pere de Casserres, which is interesting for what I do because it is a monastery that was founded by a vicecomital family where a castle that had belonged to the counts had stood, and which then became a major lord in its own right, in other words it is textbook privatisation of fiscal power but happening to an area with a church and its community in it making records, and no-one has done much on this place, which moreover still stands.2 There were other exciting aspects, such as the fact that it seems to have been closely entwined with a mother church down the river, also in a defunct castle, which never ceased to have some kind of rights there as far as I can tell, and that the clerics of these two places hardly turn up anywhere else; and the fact that when it was dug early in the century, a palæochristian altar slab covered in graffiti names came up, which has been all but ignored by the subsequent literature on the monastery, which I cannot understand.3 So I wanted to see if the names on the slab were in the charters, and those of you who heard me speak at Leeds in 2009 will know that I think some of them are.4

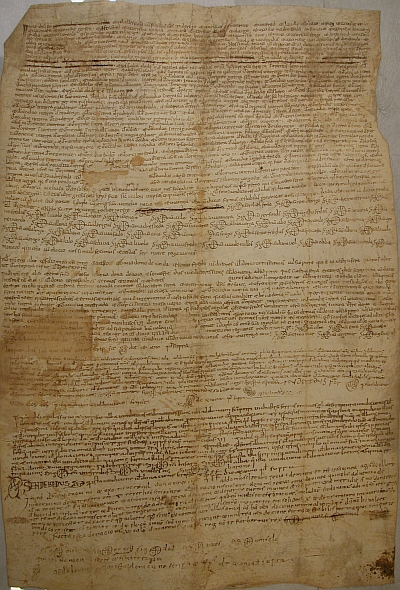

Biblioteca Universitària de Barcelona, Pergamins, C (Sant Pere de Casserres) 3: the problem charter!

That was already nearly two years ago, though, and you could be forgiven for wondering why this isn’t already submitted somewhere. Well, firstly I found out that the original surviving documents I’d looked at and the others, only preserved as copies, that I’d read in print, were not the only ones, that there were in fact about a hundred more of those copies for my period alone.5 That, as you can imagine, made a potential difference because extra evidence unhinges careless generalisations. So I found out where they were, which was in a big book in Vic, and plotted getting out there only to find, shortly afterwards, that the unstoppable force of the Fundació Noguera’s Diplomataris series had rolled over Casserres and that all its documents were now in print, and yea, even free to the web.6 So my unique selling point and first work with unpublished documents was lost, but on the other hand I didn’t have to spend a week in an archive in Vic checking my findings. So I downloaded it, found with a very quick check that the editor had not spotted the things I’d spotted about one of the documents, decided I still had a paper and set to reading it, and that’s where this post really starts. (Yes, sorry, it’s me.)

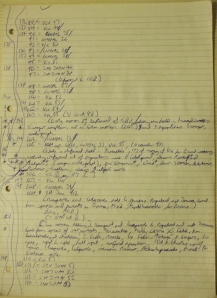

As we know I take lots of notes. When reading a few thousand charters that makes for a lot of note-taking, and all this information has to be handled. My technique for this has developed in all the wrong ways, which is to say I did not sit down and think it out and then do it the right way from the get-go, I worked with the very limited technology I had and did stupid things with it which I then bodged later. But it starts with notes, longhand abstracts of each charter mentioning things that are interesting (story kernels, as Lovecraft would have called them, or just stuff like a mill in an odd place, payment in gold not silver, bounds that don’t meet, and so on) and who’s involved, enough to come back to should I need to but not so much that I might just as well photocopy the thing or type it out. In these, some things are one-off marvels, and you get to hear about those quite often, but the real work comes in seeing people, places or things that crop up again and again, enough that we can say something safe about who they are and what they were interested in (“land”). So the notes have asterisks, for all these things that are interesting, in the margins, and lines joining recurrences up or arrows and signes de renvoi to other occurrences, and so on. (You see what this looks like above.) To actually do very much with this, however, I then have to type stuff up, firstly so that it’s electronically searchable and secondly to join up different sets of notes. If I had done this right from the start, I would I think have used a Wiki-structure database, page per charter, page per person, page per place and for each of them an entry recording where they turn up or what other entries link here. Some day when I have enough money for a research assistant this will happen. (Meanwhile, Joan Vilaseca is doing it the hard way and will within a few short years actually have the database I ought to have started with! I am continually amazed by this man’s work.) But as I started, I had no database software at all, so I typed each edition’s notes up as Word files and stuck them full of embedded links, the idea being that that way when data changed in one file it would be cascaded to all the others. Yeah, not quite. I mean, it works to a certain extent, but there is so much messy overlap, documents in several different editions, that it’s never perfect and even where it is, finding a new occurrence of a person or place tends to mean that they need updating in every file where they occur. These files are several megabytes each, they take a long time to update, they eat memory, it’s not good. But it’s what I have. So here’s a chunk, you can see what sort of information I’m recording.

53 = Cat. Car. IV 1868: is a regestum of a donation of land in Savassona with some truly impressively garbled names, a neighbour Gundolfínia and a scribe Aliborn chief among them; the land is being given by a woman to her daughter, interestingly.

54, 55, 60, 73, 76, 78, 90 & 116, perhaps among others, all feature the priest Miró, one of Casserres’s hardest-working canons and visible at the church both before and after its conversion to monastery. He is never a monk, in 73 has heirs though they aren’t identified, and buys property in own right in 78; yet his connection with this supposedly Benedictine monastery is inescapable.

54 & 78 both feature land at la Guàrdiola de Roda.

54, 78 & 140 all feature land on the strata francisca, or so the regesta that preserve this information seem to mean.

54 is a sale to the priest Miró of what seems to be most of a settlement, albeit only two pieces of land and a vine, given its bounds on others rather than people’s properties; nicely positioned on the strata francisca and its own road (presumably to Roda?); sold for only 16 solidi.

55, 56, 62, 64, 67, 80 & 114 all feature a Casserres and Roda landholder by the name of Vives, almost always as neighbour (he witnesses 56, where he is also a neighbour—but then we have so few witnesses recorded—and donates in 114).

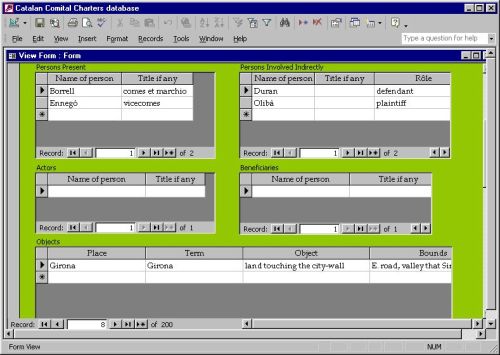

Now this is not rigorous, because its principal data capture tool is my brain, which makes mistakes. I knew this, so I was quite keen on adding databases to the mix as soon as I could. A piece of contract work for Professor Wendy Davies, all hail, left me with a good design that I customised for my own use.7 But this was within the last two years of my thesis, both part-time, and I didn’t have time or the will to type up all the charters I’d used for the project into it. Instead, I used it solely for the final chapter, the chunk on Count-Marquis Borrell II of whom you must by now all be bored (although I’m not, be warned). I typed up all documents in which he was mentioned, as atomised names and dates and so on in their appropriate fields. Running various complicated queries over that sample produced names I hadn’t noticed were recurring, whom I then went and looked for in my notes, moving thus from comitally-connected documents to regionally-connected ones, and for how that works out, you can see the book.8 And when new projects came up, I added more sections, and those you can also find lurking behind other parts of the book.9

Screenshot from my Catalan comital charters database

When I got to the Casserres charters, though, it was plain I wouldn’t have time to do it the old way, and it was also questionable whether I needed to, since I had the PDF on the computer, already searchable. It was also clear that they would have to be databased, all of them, which raised the question of what possible function longhand notes would have in the project. I was very reluctant not to make any, because atomising a document for data entry is not the same as actually reading it and I was afraid I would miss the stories that make these documents so interesting. But the Casserres ones are mainly preserved as abstracts anyway, so few stories, just bewildering obscurity, and in any case as I say there was no time. So I just data-entered the lot, all 145, three a day and more when there was time. (I’m told by an ex-girlfriend that normal people don’t get up and do academic data entry before they’ve breakfasted or dressed. But for what value of normal?10) But that’s only half the work, because you still have to get the data out and usable. That would be another piece of writing, which I think I’ve just promised to do in Italy in September so I’ll omit it here but suffice it to say, I took each charter entry in turn, I ran queries for recurrences on every name in there, and where there were some I typed them up in one of my old-fashioned files, in fact that very one I excerpt above. And then I printed it, so that there were some notes of a kind after all, which somehow makes me feel better. All the same: if this is a sane way to work, I’m a Dutchman, he says resorting to eighteenth-century ethnic slurs, sorry. (Large parts of my ancestry are fairly uncertain, in fact, but there’s no reason to suppose etc.) The fact that it just about seems to produce the results is perhaps the only compensation, and that other than recording the data better I can’t think of a quicker or more rigorous one. What do you think, if any of you made it this far?

(Of course all this is not, of itself, a new problem: check the first sentence of this article and see if it doesn’t make you cringe with complicity. Then read on. Hat tip to Ralph Luker at Cliopatria.)

1. Bede, Historia ecclesiastica gentis anglorum, V.23: “quid de his scribi debeat, quemve habiturum sint finem singula, necdum sciri valeat”, my translation.

2. Okay, there is in fact a reasonable amount of work on the place, which could probably all be found referenced in three of the four latest bits, those being: A. Pladevall i Font, J.-A. Adell i Gisbert, X. Barral i Altet, E. Bracons i Clapes, M. Gustà i Martorell, M. Hoja Cejudo, M. Gracià Salvà i Picó, A. Roig i Delofeu, E. Carbonell i Esteller, J. Vigué i Viñas & R. Rosell i Gibert, “Sant Pere de Casserres” in Vigué (ed.), Catalunya Romànica II: Osona I, ed. Vigué (Barcelona 1984), pp. 354-391, updated by J. Pujades i Cavalleria, C. Subiranas i Fàbregas, Pladevall & Adell, “Sant Pere de Casserres” in Pladevall (ed.), Catalunya Romànica XXVII: visió de sintesí, restauracions i noves troballes, bibliografía, índexs generals, ed. M. L. Ramos Martínez (Barcelona 1998), pp. 201-206, and the third Teresa Soldevila i García, Sant Pere de Casserres: història i llegenda, l’entorn 35 (Vic 1998), which is much the closest to my kind of social analysis. There is also, however, Pladevall, Sant Pere de Casserres o la Presència de Cluny en Catalunya (Barcelona 2004), which I am hoping to get hold of at last in the next few days; it’s not widely held even in Spain. With a bit of luck I still have a paper.

3. It’s been extensively written about by itself, in for example P. de Palol, “Las mesas de altar paleocristianas en la Tarraconense” in Ampurias Vol. 19-20 (Empúries 1957-1958), pp. 81-102 at p. 87; S. Alavedra, Les ares d’altar de Sant Pere de Terrassa-Ègara (Terrassa 1979), II pp. 71-74; and in Pladevall et al., “Sant Pere de Casserres”, p. 384. I owe the first two references to Mark Handley, who’s been hugely helpful helping me track this thing through the literature on stones. It is however not mentioned at all in Soldevila’s book and the Pladevall et al. article discusses it only separately.

4. J. Jarrett, “How To Take Over An Archive: Sant Pere de Casserres and its Community”, paper presented in session ‘Problems and Possibilities of Early Medieval Diplomatic, I: Pushing the Boundaries‘, International Medieval Congress, University of Leeds, 14th July 2009.

5. Somewhat amazingly, the relevant book, a 1736 manuscript copy of a list of renders and properties made for a fifteenth-century prior of the house, was found in a Tarragona bookseller’s in the 1980s; it is now in the Arxiu Comarcal d’Osona, and Soldevila was thus able to base her book firmly upon it.

6. Irene Llop (ed.), Col·lecció Diplomàtica de Sant Pere de Casserres, Diplomataris 44 (Barcelona 2009).

7. There was an expert whose identity I never discovered in that project somewhere, but since the variant design I came up with delivered the same results quicker for a megabyte less coded back-end, I’m calling it mine.

8. J. Jarrett, Rulers and Ruled in Frontier Catalonia, 880-1010: pathways of power (London 2010), pp. 140-166.

9. That on Malla and that on l’Esquerda were new work, for which I added all the relevant charters I could find to the database to produce ibid., pp. 73-99.

10. I should perhaps make clear, though, that we were long broken up when she saw me doing this.

Interesting the Australian Dictionary of National Biography project is also taking a wiki style approach as it makes it extraordinarily easy to add new material as it comes to hand – the key being to get the initial structure right which should also make it self documenting …

Yup. I had presumably heard of Wikis when I started my research, but it obviously hadn’t sunk in what they were.

Your ‘technique’ posts always make me feel guilty for being really quite haphazzard and not at all systematic about note taking and organizing, which is weird since I am probably open to clinical diagnosis of OCD in many walks of life…! Oy vey.

*goes off to begin typing up enormous backlog*

That wasn’t my intended outcome, Kath! I was hoping, I suppose, for someone to say, ‘here is software that will solve all your problems’, not to start others down my broken path! I’ll be behind you in the OCD clinic, except for small matters of oceans etc.

Well as to that, when I *do* get organized I usually do so through Endnote, and keep all my bibliographical data, e-prints and notes on same in one place. But that’s best for secondary stuff… not your mountain of charters. I had a go at making an Access database for my letters a while back, but abandoned it for similar reasons you cite above. Namely, not having a paid research assistant and/or room full of chipanzees to do the data entry for me. Still looking for a solution… and at the moment simply ‘getting by’ with a host of (mostly) unindexed and (very) inconsistently updated excel spreadsheets. Gah!

Whoops… chimpanzees, obviously.

To an extent, as Joan says, it’s not a crucial worry as long as one can work out of whatever system or lack of one one has. I suppose the issues are being sure you haven’t missed anything and, more aspirationally, whether you know all that can be known about your data (because after all, if you don’t, who does?) and that’s where the organisation might come in. But it’s not as if we have all the information anyway, and knowing how much difference that makes, for that software has yet to be invented I’m pretty sure :-/

Ha! Yes; unless there’s a TARDIS app for iPhone…

Wow, I am really flattered for your optimistic view on my limited effort in the cathalaunia website!

As for your note-taking-organization system. I don’t konw if it’s sane , probably not , (does exists a such one?) but it seems quite sound and able to deliver interesting results. So while we get to the point where machines do the hard work , that’s already quite an achievement.

I always liked FileMaker. It is a very simple database package. Sure, it is not what the experts call ‘fully relational’ like Access, but it is intuitive and fairly cheap (and you can’t say either of those things very often about database software).

No getting away from the data entry issues though, unless you use some very ‘high-end’ document review software that can cope with high resolution .tif files with very good OCR to make your scans fully text searchable. Even then I’d have said you’d still need fields that pulled out cogent data from the text (in my case (databases of epitaphs/inscriptions) it was things like dates, age, gender, names, family members, occupation, etc) – the electronic equivalent of Jonathan’s notes. Then you can run searches in those fields and not just on the main text.

While the data-entry bit is surely hugely time-consuming, there is no doubting that you learn a lot about the material in the process.

It’s certainly a good way of trapping mistakes, double attributions and the like, but as I say there is an aspect of not seeing the wood that is the document for the trees of the data that bothers me. I’m not sure I can rationally explain what might be missed by entering rather than noting, but since we know that texts are constructed it seems to me that the overall view of a piece of writing, be it in stone or on skin, can’t be completely left aside.

Back at the Fitzwilliam they managed to get quite a lot of data for the Sylloge of Coins of the British Isles database out of printed coin catalogues (and even more from the digital versions of those that had them) by OCR and then complicated automated parsing. That was possible mainly because the format of the catalogues was so standard and always broken up by the same punctuation that one could, with a certain amount of trial, error and swearing, reasonably reliably drop weight, die axis, obverse inscription, reverse inscription etc. into appropriate fields. They had a human review the results before they went live, obviously, and that was a number of days’ work, but far far easier than doing the data entry straight, and arguably not much less accurate. Certainly, even after human data entry it still needed sanity checking quite often (and that was my second job there…). So it can be done and indeed could be done in 2005 which is perhaps more significant. One’s data source does need to be extremely methodical for it to work well, though.

Pingback: The Paradox of Medieval Scotland « Senchus

Pingback: In Marca Hispanica XV: gratuitous Carolingian church sidetrack « A Corner of Tenth-Century Europe

Pingback: “No. There is… another.” « A Corner of Tenth-Century Europe

Pingback: Conferring in Naples, III: a full day’s talking « A Corner of Tenth-Century Europe

Pingback: I should arguably be using newer software | A Corner of Tenth-Century Europe

Pingback: Leeds 2013 report part 1 | A Corner of Tenth-Century Europe

Pingback: Name in Print XXIX: at long last Casserres | A Corner of Tenth-Century Europe

Pingback: A penance, a picture and a question | A Corner of Tenth-Century Europe