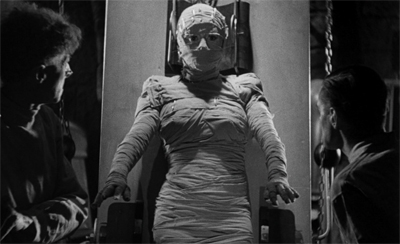

The monster demands a mate!

I always feel a little strange that I don’t completely love Bride of Frankenstein. James Whale’s Universal Monster movies are all among the very finest in the subgenre, and each of the three collected in this blu ray boxset are well worth the price of admission. And I really like Bride of Frankenstein. It’s great fun. It has a tremendous energy and surreal “buzz” around it that makes the movie fly by, no matter how many times you’ve seen it.

Whale has, as with Frankenstein and The Invisible Man, managed to draw together a fantastic cast, some amazing production design, a willingness to acknowledge the hokey nature of the material and the highest technical skill in pretty much every aspect of the finished project. And yet, despite that, Bride of Frankenstein never really feels like a single unified film. Rather, it’s a bit like the eponymous monster, strange bits and pieces from all manner of sources brought together and stitched up in a way that is far more aesthetically pleasing than its direct predecessor. I just find, personally, that with Bride of Frankenstein, the sum of the parts is actually much greater than the whole.

There is, to be entire clear, a lot to love about Bride of Frankenstein. Indeed, I am very fond of it. It does an excellent job tidying up some of the problems with its predecessor. While Frankenstein was a wonderful production, it seemed like a script pulled together from a collection of different sources, with no real character motivation linking it all together. Boris Karloff and Colin Clive did their best to pull it all together, but characters seemed remarkably flighty and inconsistent.

Those present would swap positions on the monster between scenes. Some were introduced only to serve as loose ends – with his friend Victor originally planned to be paired off with Elizabeth, a plot nixed when Henry survived the climax of Frankenstein. Henry himself didn’t seem to have a motivation. It was suggested he was pursuing forbidden knowledge, but other characters alluded to a “change” in him that was never really explained in the context of the film.

Bride of Frankenstein does considerably better with characterisation, at least for Henry. In the original film, he was hardly the most sympathetic character. Whale’s Frankenstein seemed to reserve its pity for the monster itself, the poor victim of society. Bride of Frankenstein is a lot more ambiguous, and a lot more willing to embrace moral ambiguity. Frankenstein is presented as a pathetic, humbled human being. The monster remains sympathetic, but he is also much more willing to apply brutality to accomplish his goals. Indeed, the movie opens with two rather brutal murders from the monster, of two victims who seem immediately sympathetic.

Played by Colin Clive, it’s hard to let the lines between the production and film itself to completely solidify. Whale had to deal with Clive’s alcoholism on-set, and all the cast and crew were wary of it. There’s a sense that some of that bleeds through into the performance, as Henry Frankenstein finds himself fighting an addiction to “bad science.” He tries to quit it, and to settle down with his wife, but he can’t. It won’t let him.

He’s immediately conflicted. Compare his relatively simplistic “I don’t mind if they call me mad” monologue to his conversation with Elizabeth here:

Forget? If only I could forget. But it’s never out of my mind. I’ve been cursed for delving into the mysteries of life. Perhaps death is sacred, and I’ve profaned it. For what a wonderful vision it was. I dreamed of being the first to give to the world the secret that God is so jealous of. The formula for life. Think of the power to create a man. And I did. I did it. I created a man. And who knows? In time I could have trained him to do my will. I could have bred a race. I might even have found the secret of eternal life.

He knowswhat he did was wrong, but he also can’t help but obsess over it.

Of course, part of the reason that Frankenstein seems much more morally complex this time around is the introduction of Septimus Pretorius. Indeed, the introduction of Pretorius seems to retroactively suggest the “change” alluded to in Frankenstein. A philosophy lecturer, Pretorius is clearly a heavy influence on Henry. Indeed, it seems quite likely that he “corrupted” the young man and led him down the path to those monstrous experiments.

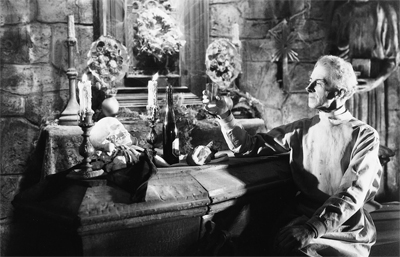

Pretorius himself allows us to see Henry as a more nuanced and rounded character, as Pretorius is very clearly the villain. Frankenstein couldn’t decide whether to condemn or sympathise with its lead character, but Bride of Frankenstein makes it rather explicit that Pretorius is not a good guy. He hangs around in tombs drinking wine and eating dinner. He hangs around with murderers. He’s completely hedonistic with both smoking and alcohol as his “only weakness.”

He has, at one point, produced a smaller version of Satan. And he remarks that the fiend looks familiar:

The next one is the very devil. Very bizarre, this little chap. There’s a certain resemblance to me, don’t you think? Or do I flatter myself? I took a great deal of pains with him. Sometimes I have wondered whether life wouldn’t be much more amusing if we were all devils, and no nonsense about angels and being good.

It’s hardly subtle, but it doesn’t need to be. Pretorius exists to make Frankenstein look like a morally conflicted, and sympathetic, character. And he accomplishes that function quite well.

Speaking about the blurring of the line between the production and the film itself, James Whale’s sexuality is frequently discussed in the context of the film. In fact, it’s frequently discussed in the context of all his films. His contemporary, Curtis Harrington, has dismissed the suggestion that Whale deliberately incorporated these themes and ideas into his work:

But I think Whale would have been absolutely astonished by such talk. Artists don’t think in terms of psychoanalytic interpretation. And I think the closest you can come to a homosexual metaphor in his films is to identify that certain sort of camp humor.

It has been suggested that Whale instructed Thesiger to play Pretorius as an “over the top caricature of a bitchy and ageing homosexual.” However, even if it wasn’t a conscious theme that Whale was developing – you could argue that it’s a logical extension of the themes of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.

After all, Frankenstein is a reproductive horror about a man taking a woman out of the reproductive process. Giving the scientist an accomplice (or making him an accomplice) adds an inherently sexual subtext, and it’s one that’s certainly heavily supported by the text. Perhaps Whale intended it, perhaps he thought it was all just a camp joke, perhaps it was something that just developed organically and has simply been interpreted that way by quite a few film scholars. Film is, after all, a subjective medium. I’d just argue that there’s a lot to support that reading.

Pretorius is, after all, the subject of the campest moment in the film, when he reveals his own experiments on the creation of life: miniature people. The first one he reveals is… a queen. Of course it is. In an earlier scene, he bursts into Castle Frankenstein to interrupt Henry and Elizabeth in their bed room – announced as “a very queer looking gentleman.” He flirtingly remarks, “I trust you will pardon this intrusion at so late an hour.” Almost immediately, he’s kicking Elizabeth out of the bedroom so he can spend some time with Henry. “My business with you, Baron, is private.”

Indeed, Pretorius seems openly resentful of Elizabeth, perhaps because she is a barrier between Victor and himself. Later on, he rather pointedly draws attention to his lack of cordiality towards her. “Baroness, I’ve not yet had the opportunity of offering you my congratulations on your marriage.” When he needs Henry to cooperate, he kidnaps Elizabeth to force his former pupil into cooperating. At one point, he seems to tease Henry with the possibility that he’s murdered her to provide organs for the Bride. He hasn’t, of course, but he seems to deliberately lead Henry to think that.

His involvement with Henry seems more than just a master and his pupil. While Henry seems ashamed of their association, Pretorius seems to want something mush more personal than a working relationship. “Before I show you the results of my trifling experiments, I would like to drink to our partnership.” Is he trying to get Henry drunk? Pretorius also plies the monster with wine when he wants to manipulate him later on. While Henry seems interested in animating dead objects as part of broader scientific questions, Pretorius seems much more focused on the act of creating life as a means to its own end.

“Creation of life is enthralling, distinctly enthralling, is it not?” he asks his former pupil. He explicitly links science to love, suggesting some sort of primal motivation for his attempt to create life, remarking, “My experiments did not turn out quite like yours, Henry. But science, like love, has her little surprises, as you shall see.” Later on, he argues, “The human heart is more complex than any other part of the body.” One would imagine that the brain is the most complex, unless he is speaking romantically – as a doctor of philosophy might be inclined to do. He seems to want to tempt Henry to join him in this mad experiment, and to abandon the pretence of the man madly in love with Elizabeth. They can create life together.

Interestingly enough, he even brings religion into it, suggesting, “Leave the charnel house and follow the lead of nature, or of God, if you like your Bible stories. Male and female, created He them. Be fruitful and multiply. Create a race, a man-made race upon the face of the earth. Why not?!” He seems to mock God’s decision to limit reproductive rights in such a fashion. Throughout this, Henry is in denial. He seems to have similar ideas, but can’t admit to them. “I daren’t. I daren’t even think of such a thing.”

“Our mad dream is only half realised,” Pretorius exclaims. “Alone you have created a man. Now together we will create his mate.” Again, Pretorius’ fascination with reproduction seeps through. He clarifies, “Yes, a woman. That should be really interesting.” The novelisation of the film is much more explicit about Pretorius’ sexuality, altering this dialogue slightly. “‘Be fruitful and multiply.’ Let us obey the Biblical injunction: you of course, have the choice of natural means; but as for me, I am afraid that there is no course open to me but the scientific way.”

I’m not so convinced, though, that there’s an elaborate homosexual reading once you get past Pretorius, who is perhaps the most fascinating character in the film. There’s something to be said about the monster’s own sexual orientation, or lack thereof. With a limited vocabulary, he uses the word “friend”to describe both the hermit and the Bride, suggesting no differentiation on his part. In fact, it isn’t the monster who demands a mate, unless you consider Pretorius the true monster of the film.

The monster just wants a “friend.” It’s Pretorius who decides that it should be female. He asks the Doctor, “You make man like me.” When Pretorius suggests making a woman instead, the monster restates his original request, as if to suggest that he simply isn’t interested in gender, “I want friend. Like me.” It’s interesting to imagine how audiences of the time would have reacted to the sight of the monster affectionately touching and caressing another male monster in that fashion.

Indeed, it seems like that film heartily mocks heterosexual unions, but I’m not convinced that this is a conscious attempt at homosexual subtext, or merely Whale’s attempts to play with audience’s expectations (or both). In the opening sequence, Byron seems far more engaged with Mary Shelley than her husband, who she refers to using his last name, “Shelley darling.” Henry and Elizabeth are interrupted in their bedchamber by an older gentleman. Even the Bride and the monster make an ineffective attempt to play at domestic bliss, making an awkward and exaggerated pantomime of a romantic coupling.

That said, Bride of Frankenstein works best adopting that ironic and subversive attitude towards an manner of social norms, a sense that Whale is playing with these ideas that society takes for granted and twisting or warping them somehow. I’m not entirely convinced the film flows smoothly – it seems to stop and start a bit – but Whale always keeps things interested by throwing all manner of ideas at the audience at one time, and leaving it to his viewers to really make sense of it all. It isn’t just marriage he plays with.

Throughout Bride of Frankenstein, Whale plays with life and death. The movie opens with the monster committing two murders, and closes with the birth of the Bride – life following death. Whale seems fascinated by the morbid obsession with death. The first two characters to die are the parents of the girl murdered in Frankenstein, and there’s something grandly tragic about their inevitable deaths.

“Oh, Hans, he must be dead,” the wife urges him. “And, dead or alive, nothing can bring our little Maria back to us.” Hans would rather wallow in his daughter’s death than celebrate her life. “If I can see his blackened bones, I can sleep at night.” There’s something quite perverse about that – the notion that a father who lost his daughter might take comfort in more death. Indeed, Whale’s entire Bride of Frankenstein seems to consciously up-end the natural progression of life and death, beginning with death and climaxing with the creation of new life.

“This is no life for murderers,” one of Pretorius’ blackmailed grave robbers comments, a wonderful line that captures a lot of the conflict between life and death quite well. Reflecting on his situation, even the monster himself admits, “I love dead. Hate living.”The monster was, as Whale seems to suggest, ironically dead before he was alive – a rather brutal upset of the natural order and something that is rather strange to think about.

Historian Scott MacQueen notes the abundant amount of crucifixion imagery in the film. When the monster is first captured, he’s tied to a stake, but with his hands by his head (rather than behind his back). When he stumbles around a graveyard, he seeks shelter under a very obvious crucifix. MacQueen argues this is another example of the inversions Whale put at the centre of the movie. The creature was resurrected and then he was crucified, rather than following the more conventional flow.

It’s full of contradictions and complexities. Then again, Whale even hints than Mary Shelley herself was full of these sorts of counter-intuitive combinations. “She is an angel,” Bryon notes of his fellow writer. She replies, coyly, “You think so?” Byron is fascinated with the idea that Mary Shelley could have produced something like Frankenstein. “Astonishing creature,” he notes. “Frightened of thunder, fearful of the dark. And yet you have written a tale that sent my blood into icy creeps.”

She replies that those two extreme ideas do not contradict each other, that she can be more than just one or the other. “I don’t know why you should think so,” she tells him. And then she suggests that it would have been inappropriate for her to play into traditional gender roles when crafting a story for Byron on a dark and stormy night. “What do you expect? Such an audience needs something stronger than a pretty little love story.”

Elsa Lanchester is cast in the dual roles of Mary Shelley and the eponymous Bride. In her autobiography, Lanchester suggests that Whale intended it as another expression of the duality and contradictions in the nature of humanity:

I think James Whale felt that if this beautiful and innocent Mary Shelley could write such a horror story as Frankenstein, then somewhere she must have had a fiend within, dominating part of her thoughts and her spirit–like ectoplasm flowing out of her to activate a monster. In this delicate little thing was an unexploded atom bomb. My playing both parts cemented that idea.

As for the monster himself, Karloff is in fine form as usual. After the original’s opening credits introduced him as “?”, it is great to see him get title billing here, his name appearing even before the title of the film itself. (Of course, the film repeats the “?” trick with Lanchester, but she – at least – is already credited as Mary Shelley.) The biggest change to the portrayal of the monster this time around is the fact that the monster can now speak.

In Frankenstein, he was mute with Karlof communicating very effectively through animalistic growls and grunts. That element remains here, with the creature acting like a wounded dog even after he has picked up a decidedly restricted vocabulary. This is a very effective way of communicating that he’s really too simplistic to really be blamed for his actions, and to garner sympathy for him despite his violent outbursts.

It’s worth noting that the monster spends the first half of the film being quite brutal. In Frankenstein, most of his murders were easily enough to justify – acts of self-preservation or tragic accidents. Here, however, the creature is shown to be capable of malice. He kills Hans in the bottom of the windmill, but he also rather viciously throws Hans’ wife down into the water as well, when there’s really no need to do so.

The creature remains childlike, but there’s a definite streak of meanness picked up. Whether that’s a result of the criminal brain that Fritz stole shining through, or if it’s simply learned behaviour from an attempted murder, is up to the audience to decide themselves. Either way, it does add an element of tragedy to the situation. While the monster was clearly persecuted by poor peasant folk in the first film, their attempts to capture him here seem quite necessary and rational. Regardless of his own culpability, he is a murderer, and he must be stopped, no matter how we feel about him.

Karloff himself was notoriously unhappy with the decision to make the monster articulate:

The speech– stupid! My argument was that if the monster had any impact or charm, it was because he was inarticulate – this great, lumbering, inarticulate creature. The moment he spoke you might as well either take the mick or play it straight.

I can definitely see where he’s coming from, and I’m honestly not sure if I agree. I do think that allowing him to articulate himself, even in basic terms, removed some of the tragedy of the creature. There’s a great scene early on where the monster tries in vain to explain his innocence to a hunting party, but can’t. However, his attempts to express himself and his basic needs using a limited vocabulary also evoke a sense of tragedy. It’s hard not to feel sorry for a monster who just wants a “friend.”

It seems that even by Bride of Frankenstein, the films themselves were confused about the name of the central monster. Shelley had, of course, intended Frankenstein to be the name of her scientist, Victor. However, in popular culture, it has become shorthand for the monster itself. Indeed, Lord Byron makes the same mistake here, calling the creature Frankenstein during the opening scene. And, of course, there’s the fact that Pretorius refers to the reanimated corpse as “the Bride of Frankenstein!”

It is, of course, a minor and nerdy note, but I’ve always found the way that concepts like that work their way into the popular imagination to be fascination, and I think it’s fair to say that Whale’s films played a pretty definitive role in drilling in the “Frankenstein is the monster”idea into popular consciousness. Among with many, many other facets of the story that weren’t present in Shelley’s original novel.

I love all that, and I love all the different elements. Still, there’s a sense that the script was still sort of hacked together from multiple drafts, all of which were stitched together to produce the finished product. Characters seem to stumble over one another in order to get the plot moving. It just happens that the monster seeks refuge in the same grave that Henry is robbing, or that the maid just happens to be leading the lynch mob.

Until the monster meets Pretorius, his subplot seems all over the map. He escapes the windmill, is captured, escapes again, finds a hermit, learns English, is discovered, is pursued and then bumps into Pretorius and joins the plot involving Frankenstein and his mentor. It seems a bit convoluted, especially the first escape from the mill and subsequent capture – surely they could have been combined.

These are, of course, very minor errors in the grand scheme of things, and it’s to Whale’s credit that he and his crew manage to perfectly compensate for any scripting problems. Bride of Frankenstein remains a beautifully constructed and thoughtful piece of cinema, one with energy to spare, and with a wealth of ideas and concepts at its core. It’s a truly great film, even if I am not quite as fond of it as most people are.

You might be interested in our other Universal Monster reviews:

- Dracula (1931)

- Frankenstein (1931)

- The Mummy (1932)

- The Invisible Man (1933)

- Bride of Frankenstein (1935)

- The Wolf Man (1941)

- The Phantom of the Opera (1943)

- The Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954)

Filed under: Non-Review Reviews | Tagged: Baroness, Boris Karloff, Bride, bride of frankenstein, Colin Clive, frankenstein, Frankenstein's monster, Franz Waxman, god, Invisible Man, James Whale, Karloff, Lord Byron, Mary Shelley, maryshelley, Shelley, Una O'Connor, Universal Monster |

Leave a comment