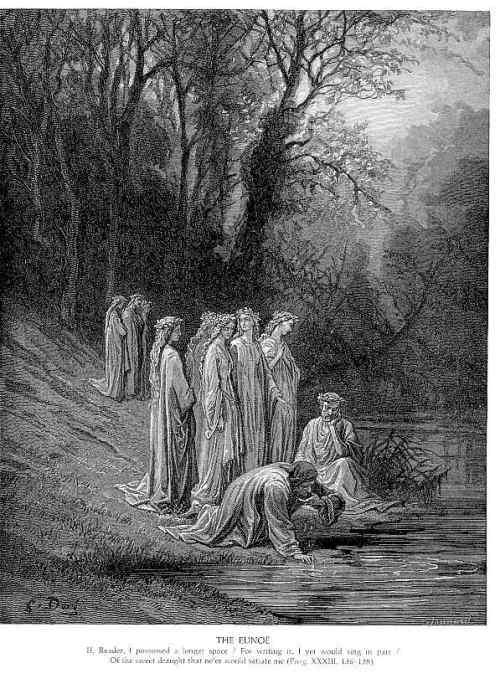

Illustration by Gustave Dore, Public Domain

Dante Alighieri is best known for writing the Divine Comedy, in which he tells a story of his soul’s journey through Hell, Purgatory and Heaven. It is one of the greatest works of literature, and here I will be so reckless as to suggest he left something out.

At the end of the second part of the poem, Purgatory, Dante drinks from two rivers, the Lethe and then the Eunoe. The Lethe is a river from Greek mythology, one of five that flowed through Hades, the underworld. Drinking it washed away all the memories of your mortal life. Dante uses the Lethe in this work, but alters its powers. Instead, bathing in the Lethe cleanses the memory of mortal sin from your mind. For Dante, the memory of sin tainted the joy of Heaven.

Dante wrote one final river into the path of the soul before it entered Heaven: the Eunoe. The Eunoe was his own creation, and not derived from Greek mythology. It roughly translates as “good memory.” The Eunoe restored or strengthened memories of good deeds performed in life, but that had been forgotten to some degree. Drinking from it prepared one for Heaven:

If, Reader, I possessed a longer space

For writing it, I yet would sing in part

Of the sweet draught that ne’er would satiate me;

But inasmuch as full are all the leaves

Made ready for this second canticle,

The curb of art no father lets me go

From the most holy water I returned

Regenerate, in the manner of new trees

That are renewed with a new foliage

Pure and disposed to mount unto the stars

Purgatorio, Canto XXXIII, Lines 136-145, Longfellow translation.

I was thinking about the Eunoe recently, and it helped me to resolve, in my own mind, some of St. Therese of Lisieux’s commentary on Purgatory, which I had always had trouble understanding.

Therese, a Doctor of the Church, offered views in various correspondence and conversations on the afterlife somewhat at odds with the settled expectation of most. Her view was that we all too willingly assumed that most people would experience a long Purgatory before entering Heaven. She viewed this as a lack of trust in the Lord, and that we should hope to enter Heaven without going through Purgatory if we adopted a childlike trust in God’s mercy.

She separately offered that it was those people who had led very meritorious lives who might have a surprisingly difficult time avoiding Purgatory. Why? Their temptation to self-justification, or spiritual pride. The following is from a conversation she had with one of her fellow nuns:

I had an immense dread of the judgments of God, and no argument of Soeur Therese could remove it. One day I put to her the following objection: “It is often said to us that in God’s sight the angels themselves are not pure. How, therefore, can you expect me to be otherwise than filled with fear?”

She replied: “There is but one means of compelling God not to judge us, and it is – to appear before Him empty-handed.” “And how can that be done?” “It is quite simple: lay nothing by, spend your treasures as you gain them. Were I to live to be eighty, I should always be poor, because I cannot economize. All my earnings are immediately spent on the ransom of souls.

“Were I to await the hour of death to offer my trifling coins for valuation, Our Lord would not fail to discover in them some base metal, and they would certainly have to be refined in Purgatory. Is it not recorded of certain great Saints that, on appearing before the Tribunal of God, their hands laden with merit, they have yet been sent to that place of expiation, because in God’s Eyes all our justice is unclean?”

(emphasis added)

So, I think Dante missed an opportunity by not adding a third river at the beginning of his Purgatory. One that lets us forget our good deeds (if we have any), at least for a while. For if you did good, was it not God’s grace that allowed you to do it? Your work was merely to cooperate with it. Drinking from this river at the beginning of the Purgatory, and the Eunoe at the end, would have been a nice symmetry.

Perhaps Dante could have called it the Aletheia, which is the opposite of Lethe. Its apparent literal meaning in Greek is “the state of not being hidden”, or “disclosure” or “truth” in shorter form.

Oh Lord, let the Aletheia run through my soul so that I may drink from it daily, and die with empty hands. Do not let me hide behind any merits that I think I may have earned. For if I do, I know that this illusion must be burned away by the fire of your mercy. Amen.

You must be logged in to post a comment.