The 5th January marks the arrival of Twelfth Night and the end of Christmas. Although barely acknowledged today – other than by the dour reminder that today is the day on which we must take down our Christmas decorations in order to avoid a run of bad luck – for centuries Twelfth Night was actually regarded as the climax of the festive period, an occasion for feasting, drinking and raucous behaviour.

Things had calmed down a bit by the early nineteenth-century but Twelfth Night was still considered to be a time of parties and merry-making. Twelfth Night celebrations in the early 1800s were characterised by the consumption of a rich fruit cake (inventively dubbed the Twelfth Night Cake) and the playing of a parlour game entitled Twelfth Night Characters. Players of Twelfth Night Characters were invited to draw a piece of paper from a hat. The paper carried the image of a humorous character accompanied by a few lines of verse which the player was expected to read aloud in the manner of their character whilst other players tried to guess who they were imitating. The game had become so ubiquitous by the turn of the nineteenth-century that printed sheets of Twelfth Night Characters were often sold alongside Twelfth Night Cakes in London’s bakeries and pastry shops. The author William Hone described these sheets of cheap, playing-card sized, caricatures as being “commonplace or gross” but considered them preferable to the more expensive versions that were peddled by the fashionable printshops of the West End, which he dismissed as “inane”.

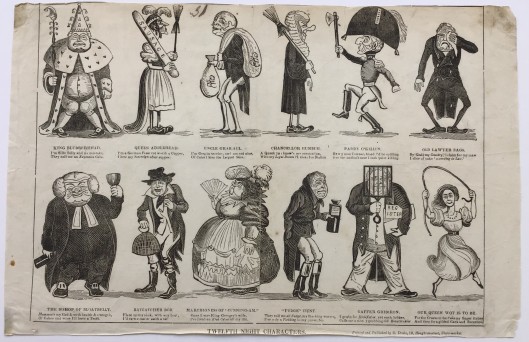

In December 1833 the caricaturist C.J. Grant used the familiar theme of Twelfth Night Characters as the basis for a political satire attacking members of the establishment. The print was issued as plate No. 31 in a sprawling series of woodcut-engraved political prints published under the collective title of The Political Drama between 1833 and 1836. Grant’s characters are: “King Blubberhead” (William IV), “Queen Addle-head” (Queen Adelaide), “Uncle Grab-all” (Lord Grey), “Chancellor Humbug” (Lord Brougham), “Paddy O’Killus” (Duke of Wellington), “Old Lawyer Bags” (Lord Eldon), “The Bishop of Bloatbelly” (a stereotypical Anglican bishop), “Ratcatcher Bob” (Sir Robert Peel), “Marchioness of Cunningham” (Lady Conyngham), “‘Fudge’ Hunt”, (Henry Hunt MP), Gaffer Gridiron” (William Cobbett), and “Our Queen Wot is to be” (Princess Victoria).

Grant was a supporter of the Radical movement which advocated democratic political, social and economic reform of the nation. Most of the individuals he caricatured were arch-conservatives who had been opposed even to the very limited extension of the electoral franchise introduced by the Reform Act of 1832 and the fact Grant chose to mock them requires little in the way of further explanation. What is perhaps more interesting is that he also pokes fun at some of his fellow reformers – namely William Cobbett and Henry Hunt. Both men belonged to an older generation of reform-minded politicians who had been regarded as Radicals in their youth but who were growing uncomfortable with the movement’s drift towards democracy and a membership which was increasingly drawn from the ranks of the working classes. Younger Radicals like Grant and his associates showed little sympathy for the reformers of yesteryear, regarding them as vainglorious old men who were too fond of prevarication and half-measures. Both Hunt and Cobbett were duly mocked for their pretensions to elder statesman status and their unwillingness to wholeheartedly embrace the philosophies of their younger associates. It is in this division that we see the seeds of the factionalism which would eventually undermine the Radicals and their successors the Chartists in the fight to make Britain a more democratic nation. Democracy would come but at a pace that was largely dictated by the ruling classes and it was not finally secured until after the mass slaughter of the First World War.

I’m particularly fond of this print as it’s an unusual example of a caricature which has been produced with an overtly tactile purpose. It was designed to be handled, cut-up and played with. Transforming an innocuous and traditional festive pastime into an act of subversion by encouraging players to mimic and thus mock the mannerisms of the Royal Family and leading politicians of the day. Using entertainment and visual humour as a means of stealthily spreading the Radical credo. It’s also one of the rarer prints in the series, presumably because so many copies were cut into pieces, played with and then thrown away.

A picture of this caricature and the other 130 prints in The Political Drama will appear in an annotated catalogue to the series which I am hoping to publish later this year.

Hi!

I came across this listing because I have several of Grant’s “Every Body’s Album” sheets with the header & issue # trimmed off, and I’m trying to figure out which issues they are. One of these has at the top a two-tiered set of “Twelfth Night Characters” which I can see has similarities to the Political Drama sheet you have shown here.

I spotted on your website that you published a book cataloguing the Political Drama sheets (and just ordered it — I wish I had spotted this prior to Christmas, as I could have asked someone to get it for me! 🙂 Looking forward to receiving it later this week.

By any chance, is there anywhere that similarly catalogues Grant’s “Every Body’s Album” series? I’ve searched the web for pictures of issues, which has helped identify some, but I’ve still half a dozen I am trying to figure out.

Thanks, Doug Wheeler

Hi Doug and congratulations on your excellent taste in reading material! Hope you find the book informative. On a more serious note; the answer to your question is unfortunately ‘no’. As with most of Grant’s output, comprehensive sets of images are not freely available online and the meaning of the designs remains obscure. You’re welcome to email me images of the plates you’re struggling with and I’ll see if I’m able to help. Although I don’t own a complete run of EBA. Best wishes.