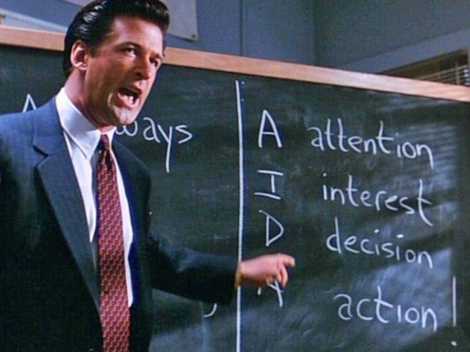

In the movie Glengarry Glen Ross, we find a powerful social commentary that offers a bleak outlook on the wage laborer, the proletariat, as Marx defined them in his Communist Manifesto. In the scene where Alec Baldwin’s character, the business motivator, lectures the salesman of a branch of his company, Mitch and Murray; his subsidiary salesmen are not helping their company, and Baldwin’s character beautifully and caustically reminds the salesmen why he is successful and they are not.

Even upon Baldwin’s first appearance in the scene, the lowly salesmen already distance themselves from him. When he says, “Lets talk about something important,” Baldwin’s character strategically urges the salesmen to make a drastic change in their business ideology; he makes it known to the failing salesmen that his approach works where theirs have failed. At the same time it doesn’t matter what follows after Baldwin’s character deems his motivational speech “important” because he already has his audience’s attention and what he offers is his own business ideology—in the sense that his ideas have worked and make more money than his audience’s, Baldwin’s character represents the ruling class’ intellectual power over the working force it exploits.

This evokes Marx’s conjecture, that, “The ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas […] the class which is the ruling material force of society, is at the same time its ruling intellectual force” (Marx 656). Baldwin’s character is the paragon of successful business (American Pragmatism) in contemporary American society, while he, too, personifies the ruling, intellectual force that posits its ideology on the working class to ensure its own survival at their cost.

Later in the Glengarry scene, Ed Harris’ character, a member of the working class, Marx’s proletariat, alienates himself from Baldwin’s character—“I don’t got to listen to this shit.” To this, Baldwin’s character responds, “You certainly don’t, pal;” the irony of this little interchange between Harris and Baldwin’s characters is that Harris, in fact, does have to listen to Baldwin’s corrosive and condescending speech because Harris is subservient and willing—he embodies the struggling working class man, who fights back against the social hegemony Baldwin enforces, but always loses.

Similarly, Harris’ character’s alienating response to Baldwin’s approach sheds light on why the working class is subservient to the elite few, who have the materials and ideology to keep their working forces in their control, for their ends. Baldwin announces, “I’m here from down town. I’m here from Mitch and Murray. And I’m here on a mission of mercy.” Right off the bat, Baldwin’s character establishes his place over the working force, his audience in the scene, and simultaneously reminds them where their paychecks are issued.

When Marx posits that, “The class which has the means of material production at its disposal has generally speaking, the ideas of those who lack the means of mental production are subject to it” (Marx 656), he focuses on why Baldwin’s character, the intermediary between the ruling and working classes (while he also represents the ruling class ideology in this scene)—this is to say that Baldwin’s character, under a Marxist light, uses the term “mission of mercy” to remind the salesmen that he has the “means of material production” at his disposal and that they are the ones “who lack the means of mental production”, that they are “subject to it” (Marx 656).

Essentially, Baldwin reinfores the extant social hierarchy in Real Estate Business by reminding his audience of their particular socio-economic location.

Baldwin reiterates this socio-economic hegemony when he says, “The good news is: you’re fired. The bad news is that you have one week to regain your jobs, starting with tonight’s sit. Oh, have I got your attention now?” In laying down his purpose for visiting his audience, Baldwin establishes the fact that they, his audience and his exploitable working force, is at his disposal and is expendable. What lies beneath this statement, is the illusion that the working class, Baldwin’s audience in this scene, has agency in becoming just like him, in rising up to a higher tax bracket. This ties in directly with what Marx says about how the ruling class tricks the working class into submission.

Marx says that the ruling class’ interest is “more connected to the common interest of all other non-ruling classes” (657); he continues to say that the ruling class’ “victory, therefore, benefits also many individuals of the other classes which are not winning a dominant position, but only insofar as it now puts these individuals in a position to raise themselves into the ruling class” (657). Aside Baldwin’s speech, Marx points to the cause of his audience’s acquiescence, willing or unwilling. The artifice Baldwin’s speech employs draws its strength from the false sense of agency he reminds his audience they have; in reality, in Marxist reality that is, Baldwin’s audience, in buying his plan for regaining their jobs, accepts the illusion that they have socio-economic mobility when in fact such mobility depends on the ruling class’ ends.

When Baldwin’s words awaken the socio-economic survival instinct in his audience, he strengthens his Logos with visual objects. Setting up the competition among his subsidiary work force, Baldwin strategically incorporates the idea of Marxist commodities in his call to action. He says, “As you all know, first prize is a Cadillac El Dorado. Anyone want to see second prize? A set of steak knives. Third prize is: you’re fired.” Baldwin’s character uses tangible objects to ground his competition. This line speaks to Marx’s theory that, “the exchange-values of commodities must be capable of being expressed in terms of something common to them all, of which thing they represent a greater or less quantity” (Marx 666). Baldwin’s character utilizes the “exchange-values of commodities” which are “expressed in terms of something common” to his entire audience to create a competitive spirit in them, but also to remind them of the socio-economic hegemony they operate under—the ruling class’. Each prize represents a different level of the socio-economic hierarchy Baldwin reminds his audience they are a part of—the first prize, the car, symbolizes the greatest material mode of economic success; the second prize, the knives, symbolize the drastic step down from success to mediocrity (in the socio-economic mobility sense); the third prize, although not material, affects the material attainment of the working class, while it also represents the drastic step down from the steak knives—that the next step down from mediocre performance is ultimate and complete socio-economic loss and hopelessness.

Likewise, when Baldwin says to Harris, “You see this watch? That watch costs more than your car,” he continues to use material commodities to make his point that he is better than his audience—that is to say that the ruling class rules with its own ideology and their success is measured in commodity. Marx says:

Commodity is a mysterious thing […] because in it the social character of men’s labor appears to them as an objective character stamped upon the product of that labor; because the relation of the producers to the sum total of their own labor is presented to them as a social relation, existing not between themselves, but between the products of their labor. This is the reason why the products of labor become commodities, social things whose qualities are at the same time perceptible and imperceptible by the sense (667).