Rhynchospora tracyi

(Rhynch-o-spora means snout seed. Samuel Tracy was a U.S. botanist.)

Cyperaceae, the sedge family

There is no point to today’s profile, no novel discovery. Just contemplating curiously a beautiful piece of creation.

Tracy’s Beaksedge graces much of the southeastern U.S. and southward usually where its feet are continually wet but not submerged perpetually, such as the squishy edges of marshes. It mixes with other species or may dominate extensive stands, spreading by thin rhizomes.

The sedge is a player in the Everglades, sometimes losing in competition to aggressive species encouraged by changing conditions.

The attractive feature of Tracy’s Beaksedge is its globose spikeball flower clusters resembling a medieval mace. Funny thing, several other soggy-foot presumably wind-pollinated grasslike marshdwellers have similar spiked globes, such as bighead rush, Juncus megacephalus; American bur-reed, Sparganium americanum; bur-sedge, Carex grayi; and Cuban bulrush, Cyperus blepharoleptos. Go figure (another day).

Young flower heads, the elongating stigmas jutting forth, no anthers visible yet.

The floral biology of Tracy’s beaksedge is odd and delicate. Each bump in the mace is a tiny branch, a spikelet. Each spikelet, within my experience, has two flowers, the larger flower having both female and male organs. The smaller flower is strictly male. Both flowers resemble microscopic ears of corn, the same shape and swaddled in green leaf wrappers. That the spikelets have an “extra” all-male flower suggests a bonus boost of pollen augmenting that from the hermaphroditic flower.

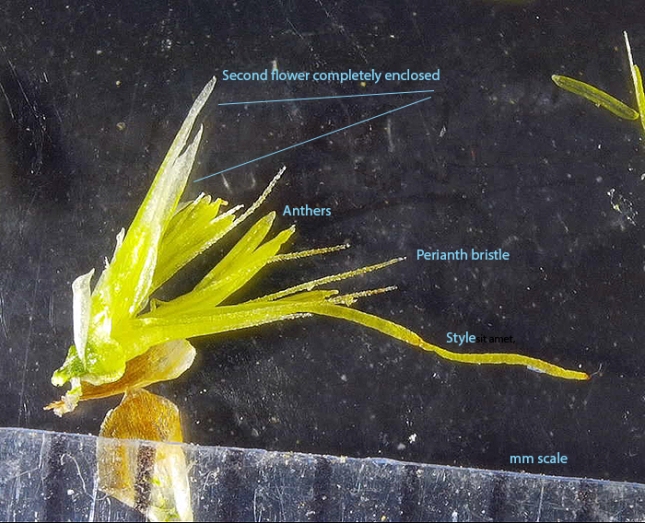

Below is a dissection of one spikelet. All the following photos are the same spikelet.

Spikelet unopened, with style to right. Scale is mm.

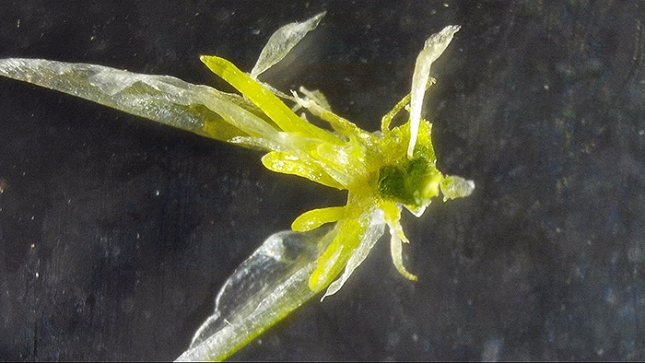

Spikelet opened, and the bisexual flower opened. Style to the right. Perianth bristles are non-sexual flower parts. Anthers are greenish-yellow. Second, male, flower is near-vertical on the left, still unopened.

The second, male, flower removed and opened. The yellow-green structures pointing left are anthers.

It might be helpful to note that the main female organs are the seed-containing ovary topped with a beaklike style responsible for capturing pollen as part of the sexual cycle. The male organs are stamens, each topped with an anther full of pollen.

In young flower heads the female pollen-catching styles poke out making the entire head a spiked ball, while the anthers remain in their wraps. The flower-head thus starts out entirely or predominantly female. The styles elongate dramatically.

Stigmas elongated. No or almost no anthers visible yet.

As the head matures, the styles elongate, twisting and curling to extreme lengths, sometimes doubling or more the length of the spikelet. They transform from little spikes into coils and curls.

Spikelet with long mature or post-mature twisty style.

As this progresses, the anthers belatedly emerge, mostly in the “middle-aged” heads. Such heads have both styles and anthers exposed simultaneously, so the two sexes seem to overlap, although the styles are mostly withering.

Middle-aged head, the styles mature and post-mature. Anthers now visible as two pale pairs at 3 and 4 ‘clock..

The long twisty styles eventually die back to stubby points, making the old spikey head look again much like the young ones. The style bases then remain as a beak on the seedlike fruit.

Older head with style bases protruding. These style bases are the beaks on the seedlike fruits.

Fruit on the right, with perianth bristles. The beak protruding to the left is the style base. Scale is mm.

How many flowers come into physical contact…you might say, “mate” during pollination? There are probably cases where wind-pollinated species in crowded stands blow into each other. I think Tracy’s Beaksedge is the world’s prime candidate for “head to head” wind-powered pollination.

The macelike heads with their styles and anthers hanging out knock wind-blown into each other all day long. I’ll bet pollen gets traded during the collisions and/or shaken loose and then exchanged over very short distances.

Normal “wind pollination” is wasteful, given that any given pollen grain has an infinitely low likelihood of docking on the stigma of another plant. It resembles hunting ducks by shooting blindfolded into the sky. Think of all the wasted ammo/dead duck! If I want to bag a quacker, my odds are better if I walk up and bean a Muscovy with a 2 X 4. (I would never do that.) Those mace-head collisions seemingly would increase the odds of pollen transfer.

The heads can have pollen stuck all over them, so if such a pollen-dusty head smacks the stigma on another head, the odds of pollination aren’t bad. The head may even collect pollen from other individuals off the wind or by collision, and then pass it along in subsequent collisions.

Note that I am not suggesting that conking heads is the only means of pollination. I don’t even KNOW if it matters. Pure speculation. How would you even test such an hypothesis? (Radioactive pollen?)

Being rhizomatous, head-bonking neighbors might be clones of each other, in a genetic sense amounting to self-pollination, although not necessarily so.

Watch Tracy’s Beaksedge bop in the wind:

Sometimes after the bonk two stems stay united:

Heads from two neighboring stems locked in embrace. Looks like a good opportunity for pollen exchange! These married couples are frequent in the marsh.