After Baudelaire, we are staying in Paris, but to get to the Situationists, it’s worth looking into some of the intermediate steps.

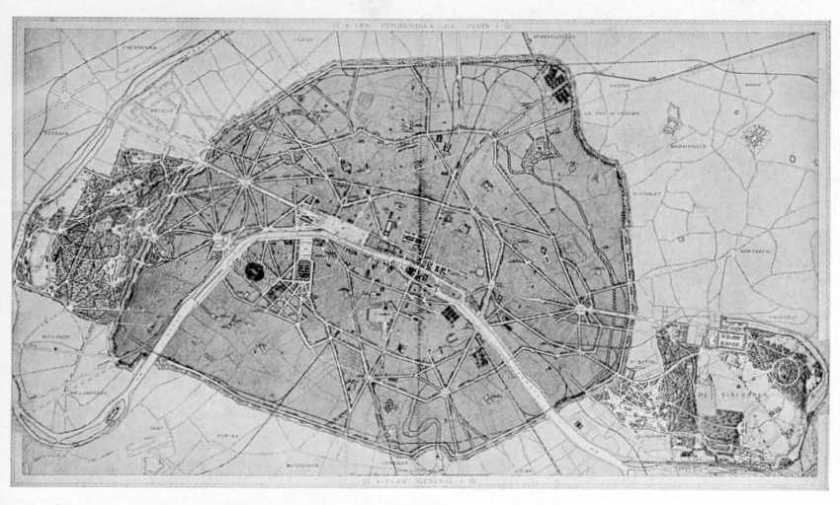

In 1853, Emperor Napoleon III (Louis Napoleon) authorised Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann to redevelop the city.

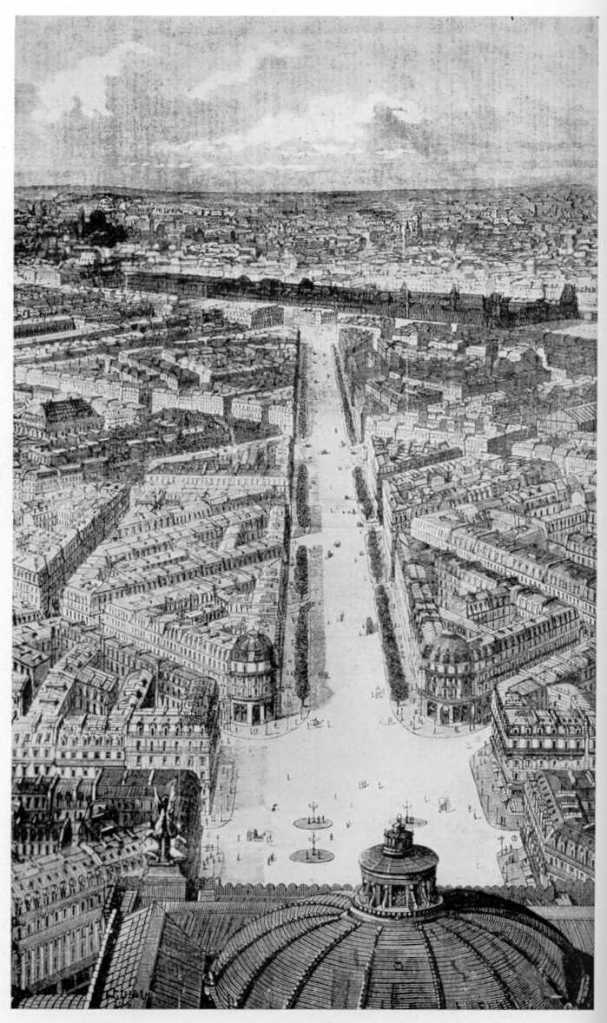

Haussmann’s plans involved the demolition of many of the arcades, and the creation of public parks and the great boulevards — known as ‘cannonshot boulevards’.

Haussmann affirmed that his plans were designed ‘to assure the public peace by the creation of large boulevards which will permit the circulation not only of air and light but also of troops.’

The Surrealist Louis Aragon (1897-1982), in his novel Paris Peasant, lamented the loss of the arcades (or passages) in the process of Haussmannisation. In a spirit which is not exactly nostalgic, but an attempt to articulate the ephemeral, he wrote,

Although the life that originally quickened [the passages] has drained away, they deserve, nevertheless, to be regarded as the secret repositories of several modern myths: it is only today, when the pickaxe menaces them, that they have at last become the true sanctuaries of a cult of the ephemeral, the ghostly landscape of damnable pleasures and professions. Places that were incomprehensible yesterday, and that tomorrow will never know.

(Aragon, Paris Peasant, translated by Simon Watson Taylor, p. 14)

The Surrealists’ influence on the Situationists was a grudging one. Speaking in 1983, Michèle Bernstein, a founding member of the Situationist International, plainly stated their position: ‘“Everyone is the son of many fathers,” she said. “There was the father we hated, which was surrealism. And there was the father we loved, which was dada. We were the children of both.”’ (Quoted in Greil Marcus, Lipstick Traces, p. 181).

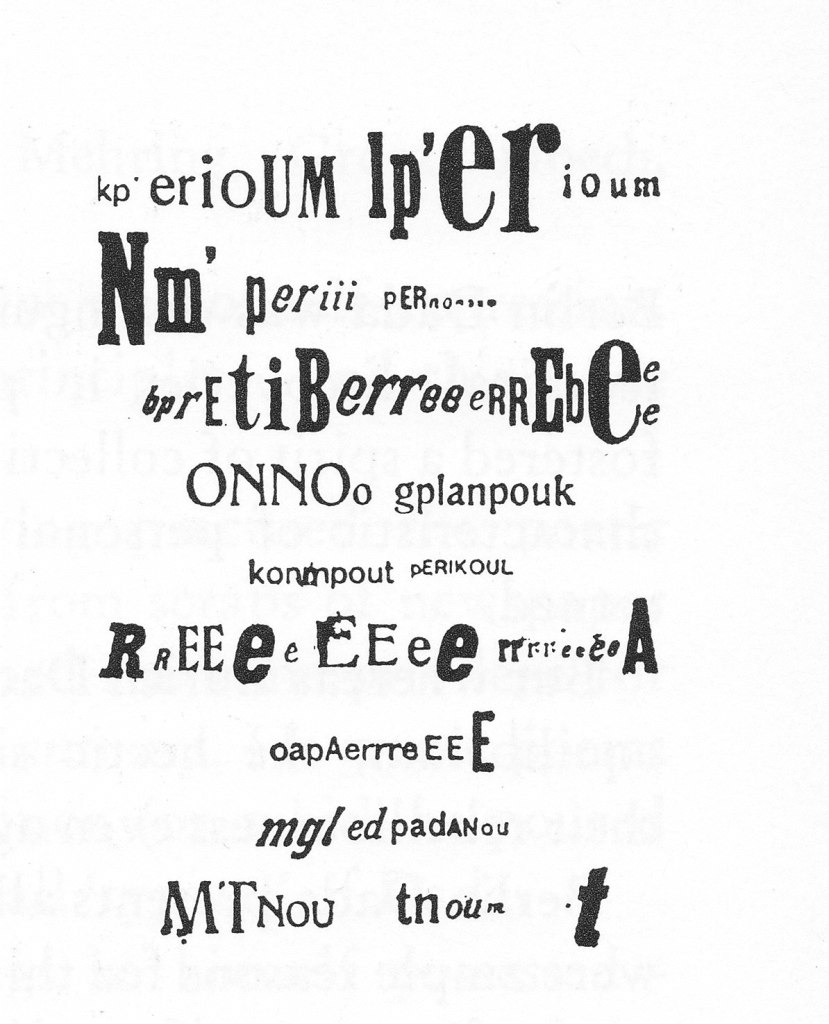

Dada, the avant-garde movement which briefly flourished at the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich (among other locations) as a reaction to the butchery of the first World War, aimed for a confrontational ‘anti-art’. An influential technique was phonetic poetry — a poetry divested of recognisable words and literal meaning, and devoted to the exploration of sound.

You can hear recordings of phonetic poems at UbuWeb (page for Hugo Ball; page for Raoul Hausmann — note especially #6 & 7).

This style of poetry was pared-down even further by Isidore Isou (1925-2007), founder of the Lettrist movement. (Listen to him reading his poems here.) And it was from the Lettrists that, in 1952, following a violent disagreement about Charlie Chaplin’s visit to Paris, the founding members of the Situationist International, led by Guy Debord, split.

In the arts, the Situationists’ other main influence was Isidore Ducasse, known as Compte de Lautréamont (1846-1870). Lautréamont is best-known for his transgressive Les Chants de Maldoror, but it was his Poésies which inspired the central Situationist tenet of détournement. This idea may be defined as plagiarising existing materials and adding new meaning, inverting the meaning, or otherwise altering the original. The aim of this is to expose and oppose the spectacular nature of cultural products. Guy Debord and Gil J. Wolman clarified:

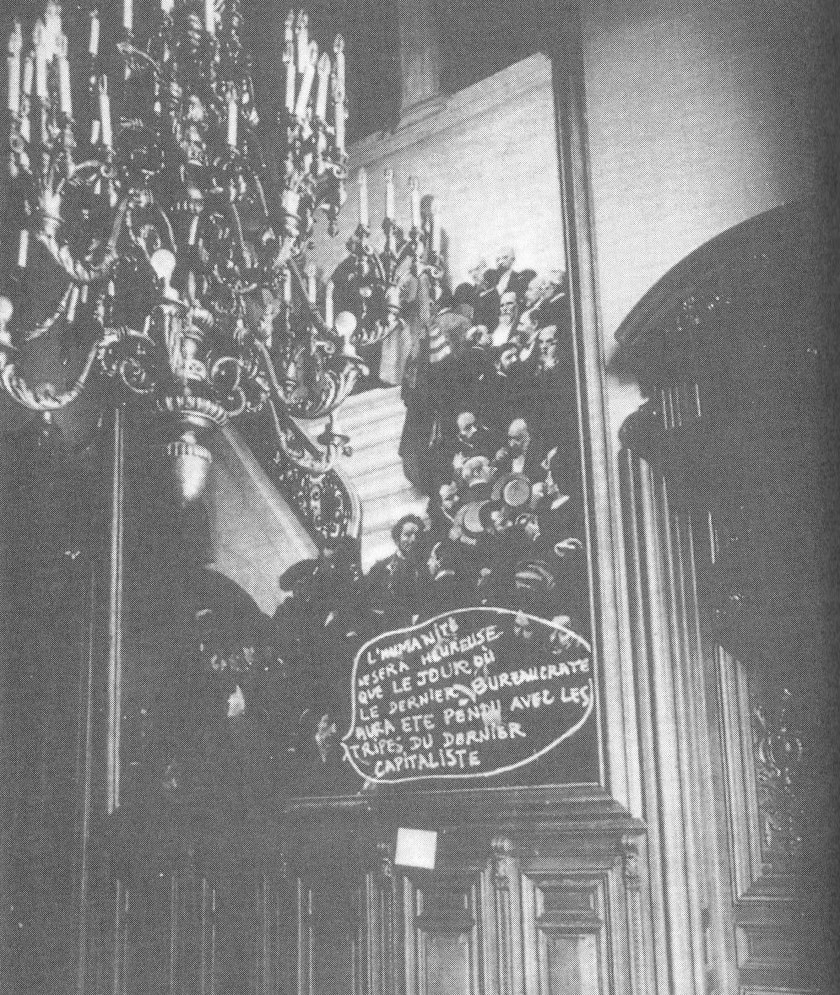

The literary and artistic heritage of humanity should be used for partisan propaganda purposes. It is, of course, necessary to go beyond any idea of mere scandal. Since opposition to the bourgeois notion of art and artistic genius has become pretty much old hat, [Marcel Duchamp’s] drawing of a moustache on the Mona Lisa is no more interesting than the original version of that painting. We must now push this process to the point of negating the negation.

(‘A User’s Guide to Détournement’ (1956), translated by Ken Knabb.)

As much as the Situationist International was an artistic avant-garde movement, it was a politically radical one, drawing on G. W. F. Hegel (1770-1831), Ludwig Feuerbach (1804-1872), Karl Marx (1818-1883), György Lukács (1885-1971), and Henri Lefebvre (1901-1991). They developed a critique of capitalist / consumer society which they defined in terms of the ‘spectacle’. Briefly put, the society of the spectacle describes a theory of human relations in capitalist society which regards life as mediated by images. It may be regarded as an extension of the Marxist critique of alienated labour, where the spectacle infiltrates all areas of life: not only the work-place, mass media, and consumerism, but also what is regarded as leisure time.

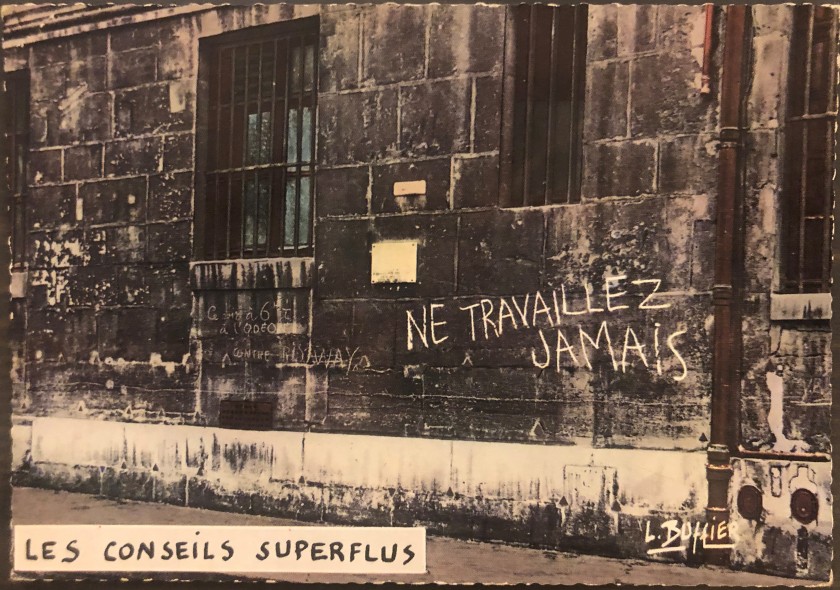

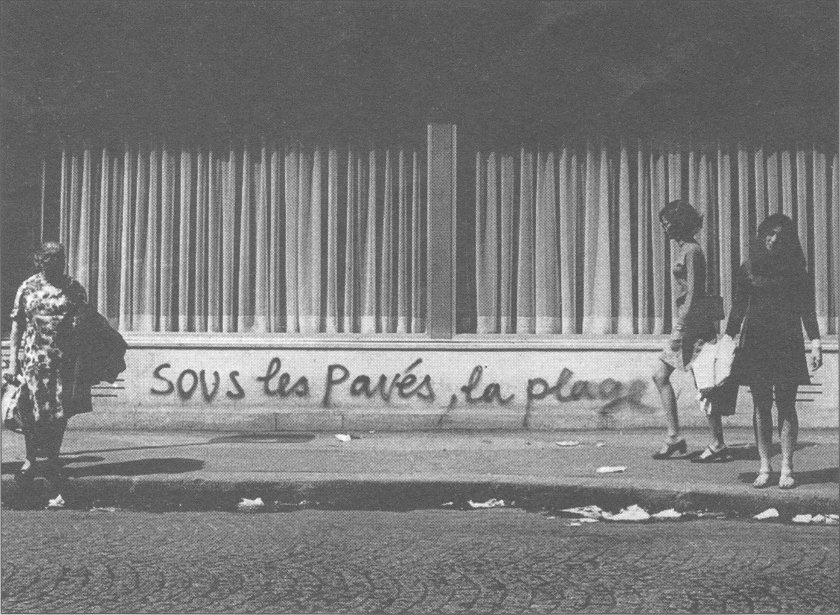

Situationist ideas were influential during the events of May 1968 in Paris, but the Situationist International did not last long after the revolutionary failure of that moment, finally disbanding in 1972 after numerous resignations and exclusions.

The legacy of the Situationist International has been the source of much conflict, particularly between those who would claim them as a vital political movement, and those who focus on their contribution to (anti-)art and the avant-garde. Certainly, as a critique of consumerism and media in capitalist societies, the Society of the Spectacle remains valid and illuminating. Similarly, their posture of negation (which, somewhat comically, resulted in the expulsion of the majority of their members) can be a bracing corrective to any complacent tendendies we may have with regard to contemporary culture.

But for our purposes, the theory of psychogeography and the practice of the dérive are essential for our urban wandering.

The dérive is sometimes translated ‘drift’. It is a ‘technique of rapid passage through varied ambiences’ (‘Definitions’, Internationale Situationniste #1, 1958). Dérive is a mode of navigating the city according to the spirit of détournement: not random (although chance can play a role) but responding to intuitive or emotional desires to connect disparate regions.

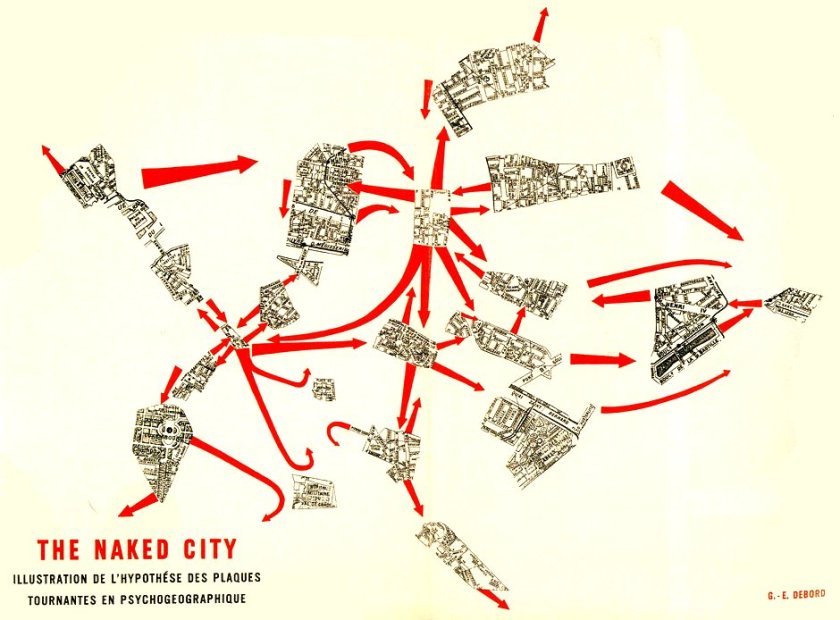

Psychogeography is ‘The study of the specific effects of the geographical environment (whether consciously organized or not) on the emotions and behaviour of individuals’ (‘Definitions’, Internationale Situationniste #1, 1958). It is the theorization of the praxis of dérive: the redrawing of the city’s map in relation to randomized, intuitive, anti-cartographical associations of atmospheres and emotional response to the environment.

Debord wrote,

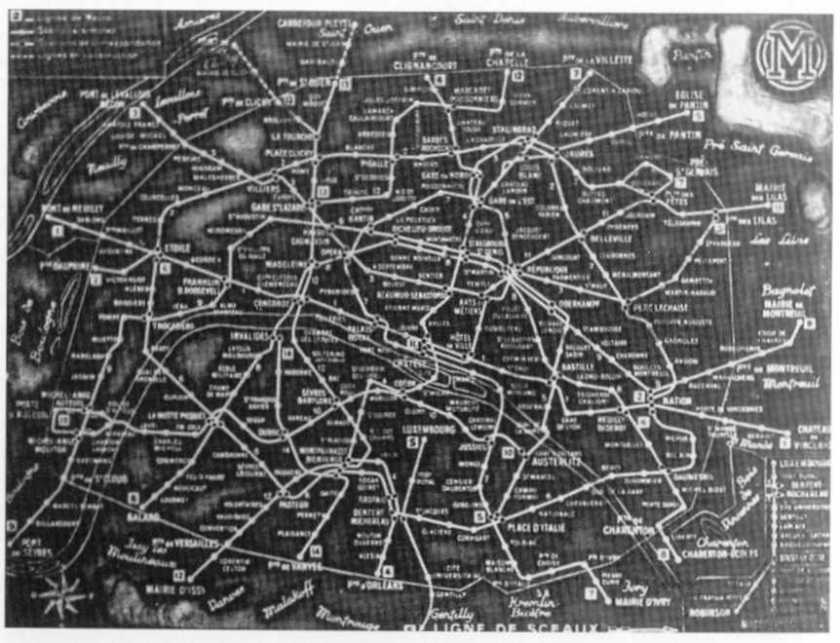

I scarcely know of anything but those two harbours at dusk painted by Claude Lorrain—which are in the Louvre and which juxtapose extremely dissimilar urban ambiances — that can rival in beauty the Paris Metro maps. I am not, of course, talking about mere physical beauty — the new beauty can only be a beauty of situation — but simply about the particularly moving presentation, in both cases, of a sum of possibilities.

(‘Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography’ (1955), translated by Ken Knabb)

The metro map connects individual named places with others by a network of lines which bend and cross each other, creating associations between distant points which disregard scale and the architecture around these points. So we can see the influence on the cut up plans of Paris designed by Guy Debord and Asger Jorn. By linking disparate areas of the city with routes that disregard distance and scale, and the lines of the street plan, these maps are visual representations of the potential of the dérive.

3 thoughts on “Situationists and the dérive”