As a young boy turtles played only a small role in my life. While weeding my mother’s garden or playing in the back yard I came across the occasional boxer turtle. Bemused by the slow moving animals I loved watching their halting movements through the underbrush. It never occurred to me turtles could be a source of food or reinforce social status. How unaware I was! A recent review of whaling journals at the San Francisco Public Library has made clear how little I still know about the central role of turtles and turtle soup on whaling voyages in the Age of Sail. It is Americans’, particularly whaling seamen’s, fascination with sea turtles during the Age of Sail and how turtles and turtle soup helped shape identities that I want to discuss in this post.

With the exception of New Orleans restaurants and some cruise ships, there are not many American public dining spaces that today serve turtle soup. Most contemporary Americans have never eaten turtle soup. The same could hardly be said for early settlers of the Americas or their European cousins. Englishmen sailing to Virginia who found themselves shipwrecked on Bermuda in 1609 subsequently set out for Virginia on the Sea Venture with supplies that included green turtles. Despite early seventeenth century attempts to limit harvesting of turtles the Bermudian turtle population was quickly depleted. As a result, Europeans spread out over the western Atlantic to Florida, the Cayman Islands and elsewhere in search of turtles. Turtlers, i.e. small vessels harvesting turtles, became an important component of the Western Atlantic maritime economy. These small vessels were critical to the development of a web of commercial connections whereby turtles were captured and then shipped to North American and European consumers.

In the ensuing centuries overhunting resulted in turtle canneries, such as A. Granday’s of Key West, having to limit their production of turtle soup, and eventually lead to strict regulation of turtle harvesting. With the passage in 1971 of the Endangered Species Act, killing of sea turtles in United States waters was prohibited and Granday’s and other turtle canneries went out of business.

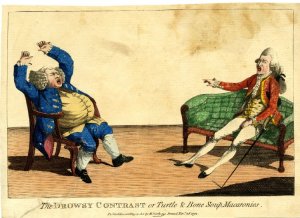

But in the 18th and 18th centuries turtles were an important food staple in the Atlantic. A market for turtles and turtle soup was well developed in England as early as 1753 when Gentleman’s Magazine contained several notices of large sea turtles being dressed in London public houses. Demand for turtles grew so significantly that ships from the West Indies constructed wooden tanks in which live turtles could be transported. And an association between turtle soup and upper class pretensions developed fairly quickly. Even before the American Revolution turtle soup was associated with fops or dandies, wearers of macaroni wigs.

“The Drowsy Contrast or Turtle & Bone Soup Macaronies” http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details/collection_image_gallery.aspx?assetId=124832&objectId=1619123&partId=1

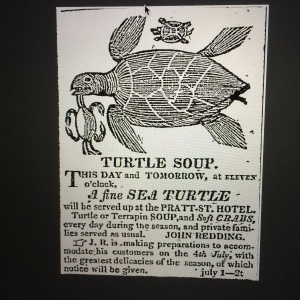

Residents of North American were not far behind their British cousins in both developing a taste for turtle soup and associating its consumption with refinement. It appears that Charleston was the first major North American city which developed a market for the consumption of turtle soup in public dining spaces. Given the city’s proximity to West Indian and Floridian sources of sea turtles this is hardly surprising. In 1784 the Charleston Coffee Shop offered “Turtle Soup every Monday, Wednesday and Friday.” Soon competitors such as Moore’s Exchange Coffee-House and Tavern and Browne’s Eating-House placed similar notices in local papers. By the 1790s advertisements regularly appeared in New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore and Boston newspapers offering the public “Real Green Turtle Soup!” that was “of the best quantity,” while “gentlemen of the city” were urged to partake in dinners in which turtles would be “dressed in the finest style” before heading to the theater.

The popularity of turtle soup during the 18th century is also apparent from the1798 country dance called “Turtle Soup.” (Those of us of a certain age might remember the Turtles‘ last album was called “Turtle Soup.” I doubt that Flo and Eddie were inspired by the eighteenth century dance, but stranger things have happened).

In the first three decades of the nineteenth century, whether dancing to the sounds of “Turtle Soup” or not, many Americans and Europeans who were or aspired to be among the leisure classes ate turtle soup. Dining proprietors in Newburyport, Salem, Hartford, Newport, Providence, and Albany all advertised that turtle soup was on their menus and sought “gentlemen” to feast on the delicacy. Turtle soup came to be seen as a symbol of Victorian opulence, associated with lavish Lord Mayor’s and aldermen’s banquets. At most such galas, as well club dinners at hotels such as Young’s, the Parker House and the Albion Hotel, turtle soup was almost “invariably offered” as the first course of a extensive menu. Well off families were urged to have their servants pick up soup so the “families can be supplied.” In contrast workers who crowded into noisy crowded nineteenth century sixpenny restaurants where rapid fire meals were consumed in less than thirty minutes did not expect to be served turtle soup.

The expense of turtle soup and what Miss Corson’s Practical Cookery’s calls the “inconvenience” for families in killing large turtles did not stop those of limited means from aspiring to eat turtle soup. Price may have deterred workers from purchasing turtle soup but inventive cooks soon came up with an alternative – mock turtle soup. Mock turtle soup was popular in both England and North America and recipes for it can be found cook books of the late 18th and early nineteenth centuries. Typically , as did Mrs. Raffald’s 1807 Experienced Housekeeper recipe for “artificial” turtle soup, calf’s head was used to provide the gelatinous texture found in traditional turtle soup. But whether the mock turtle soup utilized calf’s head or fried ham it offered workers a means to experience the pleasure and associations of turtle soup without the expense or fuss involved in killing a large turtle.

For seamen whose diets were, to be charitable, dull and unvarying, sea turtles offered both an opportunity to ‘spice up’ their diet and partake in an activity that on land was generally limited to those of greater means than the typical Jack Tar.

Baltimore Patriot, July 1, 1821

Sailors, particularly whaling seamen, had a good deal of experience capturing and eating turtles. This resulted in mariners expressing preferences concerning the types of turtles they ate as well as how the turtles were prepared. New Bedford men often considered the green turtle “somewhat coarse food” causing them to leave the “flat-shelled fellows on the beaches behind us.” However, Massachusetts whalers did like terrapin turtles that they toasted, claiming that toasted terrapin was “sweeter than almond.” Other seaman, such as William Whitecar, expressed a preference for Madagascar terrapins. Whitcar and his mess mates found that despite some turtles having lived in the ship’s hold for a year they were “quite fat, and [provided] a delicious meal.”

When whaling crews captured large numbers of turtles ships’ cooks were said to create dinners “surpassing a civic banquet in the quality and quantity.” Given the immense size of some sea turtles, which could weight as much as two hundred pounds, the killing and cooking of these animals in the tight confines of a whaling ship was no easy feat. Sailors appreciated the efforts of ship cooks in preparing turtle meals. The mariners described their dinners of turtle meat and/or turtle soup as “feast[s] fit for a prince.” In describing turtle dinners on board a whaling ship the American seaman Thomas Beale remarked that “our black cook” had presented a feast that was “aldermanic.” Clearly Beale and other whalers enjoyed the fact that despite their physically demanding and often isolated lifestyle they were able to partake in eating high end food and engaging in a dining experience that on land was generally only experienced by more wealthy individuals such as aldermen. Whether the turtles they ate were green turtles from Florida, Madagascar terrapins or Pacific sea turtles, seamen’s dining on turtles constituted an inversion of usual class roles. Whaling seamen engaging in turtle fests at sea was the maritime equivalent of Election Day or Pinkster Day, where a black slave was elected Governor for a day. While neither turtle-fests at sea nor Election or Pinskter Days undid existing class structures, they did provide the underclass – sailors and slaves – a brief respite in which roles were reversed.

Wealth typically translates to greater health, meaning wealthier individuals who can afford better quality and diversity of food on average live longer. It is likely that eating turtle meat and soup allowed some unknown number of whaling seamen to reap benefits of a more diverse diet typically limited to those of greater means, and perhaps live longer lives than seamen who had less diverse diets.

What might be most interesting about the class implications of turtle soup is how long it retained its character as a dish for society’s elites. When John Lusty, chairman of the English firm which imported turtles, died in 1947, his obituary noted Lusty’s turtles had “graced the table of many a prince and society hostess,” as well as three monarchs. And yet, as the below image of Worthman’s Mock Turtle Soup indicates, even today there are still some who cannot afford turtle soup who seek to enjoy the luxurious experience associated with eating the soup without paying its cost.